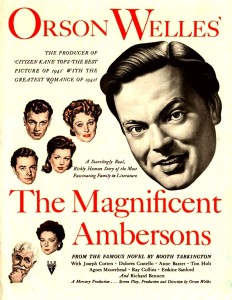

Suppose – just suppose – Orson Welles had made The Magnificent Ambersons in 1941 and followed it with Citizen Kane in 1942 instead of the other way around? A Booth Tarkington tale about Midwestern gentry at the hinge of the 19th and 20th centuries may have lacked the without-a-net audacity of an epic inspired by the life of a powerful media lord. But one guesses that Ambersons would have been just as innovative and, over time, just as influential as Kane turned out to be.

Welles still might have gotten into the same amount of trouble with William Randolph Hearst and his friends over Kane. But maybe Ambersons, assuming it was successful enough, would have smoothed the director-impresario-genius’ path at the outset, making smear campaigns or other potentially nasty dustups less damaging over the long haul.

Think of what an empowered, professionally secure Welles could have done throughout the subsequent decades…

Of course, such “might-have- beens” and “should-have- beens” are littered all over Welles’ life story. (I still think Welles, who by that time had little else going on, should have run in his native Wisconsin against “Tail Gunner Joe” McCarthy for the U.S. Senate in 1946. Talk about a real might-have-been…)

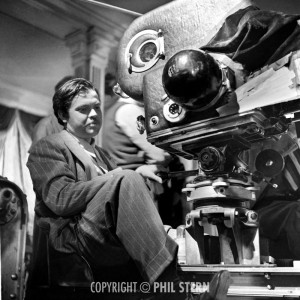

Anyway, here’s what really happened: Welles’ control of The Magnificent Ambersons‘ final cut was taken out of his hands by the same RKO Studios that had all but given him the keys to the castle a few years before. The movie’s original 2 1/2-hour and 12-minute running time had been whittled down to 88 minutes. (The whole time this surgery was taking place, Welles was spending a lot of time in Brazil directing the visual potpourri whose surviving fragments would surface in theaters decades later as It’s All True.) When the dust settled, The Magnificent Ambersons, which many, including Welles, have contended to be an even greater movie than Kane, was regarded as a noble fiasco and marked the beginning of Welles’ wilderness years.

If you’ve never seen the movie before, prepare to discover, one of the most hauntingly

beautiful American films ever made. It transfigures elements of Tarkington’s novel into a vision of lost time. It tells of dreams literally squirming away from the grasp of its well-heeled characters.

There is, first and foremost, Eugene Morgan (Joseph Cotton), an auto tycoon who returns to his Hoosier hometown with his vivacious daughter, Lucy (Anne Baxter), partly to win the heart of Isabel Amberson Minafer (Dolores Costello), whom he’d loved and lost as a younger man. With her husband’s death, Isabel seems poised to fulfill Eugene’s long-withheld yearnings – except that her son, George (Tim Holt), a spoiled, insolent brat, stands in Eugene’s way. Forced to choose between Eugene’s promise of love and financial security and George’s petulant, inchoate neediness, Isabel opts for the latter, with dire consequences.

As you watch this film, you’re so enraptured by its visual sweep, narrative detail and resonance that you wonder what its lost 44 minutes could have added. Or is one’s knowledge of irretrievable scenes and dialogue part of what adds to The Magnificent Ambersons aura? I’m still trying to figure it out.

But there are some things I do know for sure: for instance, the scene of Eugene and Lucy stepping out of a winter’s night into a luminous, festive parlor that seems to swallow us all in a welter of gaiety and promise. Generations of filmmakers would break their necks trying to match that set piece, and few have even approached its magic.

And then there are the actors. Holt, whose only other movie role of lasting consequence came in 1948’s The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, has been viewed as a surrogate for Welles himself as George, but the director wisely thought it would be best if he sit this one out. He couldn’t have done better than Holt. Cotton is grave, sad and unassumingly noble as Eugene, while Baxter shows precocious control of her character’s unsettled temperament. Most of all, there’s Agnes Moorehead as George’s Aunt Fanny, who may well be the most romantic dreamer of the family and feels the most pain from forsaken hope.

As with Kane, one is always aware of what Ambersons is transmitting, through the code of the subconscious, about its director’s personality and long-range future. The “comeuppance” that townspeople are awaiting for George Minifer looms larger with every rash act of hubris. And when it comes, hardly anyone is around to notice or appreciate it.

If you know anything at all about what happened to Welles after this film was made, this is the kind of detail poignant enough to sting your eyes.