If you heard my annual song-and-dance on the Dec. 26 edition of “The Colin McEnroe Show” on Hartford’s WNPR-FM, you’re aware of at least one of my “oopsie” omissions from my Best-of-2013 jazz recordings list. And since that particular omission gets more embarrassing every time I listen to it, I am obliged to start 2014 by elaborating upon my mea culpa – and mention at least one other omission at length. And since we don’t want to be too negative with a clean slate, I’ll add some spare change on the first new disc of the year that’s got my (mostly appreciative) attention.

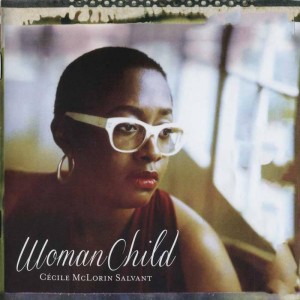

Cecile McLorin Salvant, “WomanChild” (Mack Avenue)— Whenever a vocalist catches fire on the jazz scene, it often happens after he or she has been out in the world for some time. In the nineties, as in the case of Shirley Horn or even Abbey Lincoln, there was the phenomenon of rediscovering artists who’ve found a glorious second wind carrying them late in life to unexpectedly fresh levels of expression and power. Rarely do young jazz singers make your head turn at Jump Street the way Willie Mays raised heart rates with his first-at-bat. Which makes Cecile McLorin Salvant, at just 24 years old, an especially rare talent. To repeat what I said on Colin’s show, she is simply the most exciting young jazz vocalist I’ve heard in at least a quarter-century, which I suppose constitutes a generation. To move down the checklist: Tone: Check; Dynamics: Check; Phrasing: Check – and she has the ineffable qualities that in their rawest form we recognize as “soulfulness.” But even with all those attributes in her tool kit, Salvant makes her biggest impression on “WomanChild” with the intelligence and breadth of her repertoire. She makes a couple of customary stops on the standards tour (“I Didn’t Know What Time It Was”, “What a Little Moonlight Can Do”). But she also reaches waaaaay back to the less-travelled, but venerated pathways cleared by Bessie Smith (“St. Louis Woman”), Clarence Williams (“Baby Have Pity On Me”), Fats Waller (“Jitterbug Waltz”) and, most stirring of all, Bert Williams (“Nobody”). When someone so young can do so much at once, the immediate worry is that she’ll spread herself too broadly before she Finds Herself (whatever that means). I prefer to enjoy the rush of potential and possibility as she steps to the plate for another cut at history. I also want to shout-out to her comparably promising pianist Aaron Diehl, who flashes his own bright-burning composite of lyricism, eclecticism and dynamism.

Jane Ira Bloom “Sixteen Sunsets” (Outline) – You could more accurately title it, “Sixteen Ballads,” but “Sunsets” sounds more appropriate, metaphorically. And as with reach sunsets, each of these ballads enraptures in different ways. She uses what she loves about the classic melodists, including Gershwin (“But Not For Me”), Arlen (“Out of this World”) Waldron (“Left Alone”), Kern (“The Way You Look Tonight”) and Weill (“My Ship”) and brings their deceptively simple designs to her own compositions, including “Primary Colors,” “Too Many Reasons”, “Ice Dancing” and my own favorite, “What She Wanted.” Her soprano saxophone can make your skin tingle as few others on her instrument ever have. If this disc, as with Salvant’s, had arrived in my mailbox before I turned in my ballot to the NPR Jazz Critics Poll, my Top Ten List would have been very different.

Matt Wilson Quartet with John Medeski, “Gathering Call” (Palmetto) – What an pleasurable way to start the New Year: Hard bop, late-1960s/early 1970s vintage, played without apologies and with an open-hearted joie de vivre that can make even the hardest of hard-core progressives wonder why they ever thought the genre was old news. I suppose some would still think it old news, even if they liked it. But there’s nothing musty or creaky about Wilson’s easygoing command of the trap set in all situations or his group’s saucy renditions of such Ellingtonia as “Main Stem” or “You Dirty Dog.” The quartet also pays homage to the recently departed bassist Butch Warren by playing the latter’s “Barack Obama” with the delicacy, wonder and cautious optimism you suspect the composer had in mind as he wrote it. You’re happy for the leader, one of the perennial Good Guys in the jazz business, which in turn makes you happy – and hopeful – for the business itself.