Don’t know whether you’ve heard or not, but as of this year, professional basketball has become the Number One Sport in America. Many can, and likely will argue with me on this and we can do so another time. But I know that with this prominence has come some chatter among the philosophically inclined (or challenged) about how basketball is such a prototypically American team game where everybody plays together as a unit while allowing individual brilliance to come forth in dramatic ways while playing within the rules and blah-de-blah-blah…

I mean…I know that ALL team sports allow for that to varying degrees, right? But the basketball cognoscenti contends that it’s the grand, freewheeling and often explosive manner in which players express themselves spontaneously within the confines of the game that solidifies its global appeal. (Once again, blah-de-blah-blah-and again we can fight about this later.)

The only reason I’m bringing it up here is that there was a time — and not all that long ago — when people spoke in this manner about jazz music, another American-born enterprise allowing for, even compelling individual spontaneity within a collective endeavor. Both basketball and jazz have deployed “jam” and even “jam sessions” in their argot, though they technically mean different things. And, as is especially the case with the pro game, basketball depends heavily on stars drawing fans’ wayward attention spans into the not-always-conspicuous-but-deeply-satisfying graces within the sport. Jazz likewise searches far and wide for first-magnitude stars and doesn’t lack for hot young “phenoms” of its own. (Number 1 on this list.) It also has ageless wonders who can still “ball” with eye-popping agility (Numbers 2 and 7), slammers who aren’t afraid to go hard and inside (Numbers 4, 5 and 10) and sharpshooters with wide wingspans (Numbers 3, 6, 8, 4 and 1, again).

I just wish I knew the secret to jazz drawing in, at the very least, the savants who care so much about whether the “Dubs” (look it up) repeat again as champs or whether the Celtics-Sixers rivalry is really going back to where it used to be in the 1980s/1960s or whether LeBron James is gunning hard for a third MVP award or whether the Thunder has too many shooters, etc. Why can’t jazz get buzz like that?

Because, as with everything else in the recording industry (whatever the hell THAT is these days), jazz’s future is locked in a chrysalis forged by changes in distribution, marketing and even packaging. (How long and deep is the vinyl resurgence anyway?) And when the chrysalis bursts, then what? Or, more to the point, so what? Jazz isn’t in a position to lead change, but it will, or should adapt to the changes overtaking the American psyche in matters of gender, economics and, as always, race, defined here a mythic construct that nonetheless holds American minds hostage.

(We can table that discussion for another time, too.)

Through it all, the music abides. And, for anybody bothering to listen, it’s stronger, livelier and more vibrant than ever. Case in point:

1.) Cecile McLorin Salvant, Dreams and Daggers (Mack Avenue) – As of this album, her third (or maybe fourth), it is no longer enough to say she’s the most talented young vocalist to appear in decades. Nor is enough to say that she’s the best jazz singer of her (Millennial) generation. This double disc package, composed mostly of sets gathered from a September, 2016 Village Vanguard engagement, proclaims Cecile McLorin Salvant as a star of such near-blinding magnitude that if I could have given the first five spots on the list to this album, I would. Put another way (and I apologize if I’m repeating myself): I cannot remember ever hearing a singer achieving before the age of 30 such a formidable command of rhythm, tone, nuance, articulation and idiom. Prodigies before her have come and, often, gone with her abundance of resources. But among many other things, she can bend, without undue distortions, any phrase in any standard, allowing the familiar lyrics in such chestnuts as “You’re My Thrill,” “The Best Thing For You”(with its challenging chord and line shifts), “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was” and “Let’s Face the Music and Dance” to lope around, lag behind and leap ahead of their assigned tempos with a veteran’s imperturbable authority. As she has in her previous albums, she pounds hard-core blues tunes such as “Sam Jones’ Blues” and “You Got To Give Me Some” as if born and bred in brawling roadhouses. But she treats the words of these raw-boned songs with same solicitude and care that she applies to the suave cheekiness of Bob Dorough’s “Nothing Like You” and “Devil May Care” or to the ruminative pathos of the Jule Styne-Bob Merrill plaint, “If a Girl Isn’t Pretty.” She is a skilled dramatist, probing and engaging the character behind each song – though I wish another dramatist would someday fashion a vehicle that could showcase her brilliance on stage or screen the way Funny Girl delivered Barbra Streisand to the center of the universe. She’s also playful, but she aint playing. Nor is she a dilettante wandering aimlessly, from show tunes to primordial funk and back to her own original musings (“More,” “Red Instead.”) She’s probing for connections, linkages, overlapping characteristics of each tune with the kind of fortitude that over time could reinforce the foundations of American music for new generations of players, poets and lovers. And, as I may or may not have mentioned earlier, she’s only 28 years old. I did neglect to mention the comparably dynamic support of her rhythm section, especially pianist Aaron Diehl, who’s becoming a first-magnitude star on his own. I can’t tell you any more. There are some things you’re going to have to see and hear for your own selves.

2.) Ahmad Jamal, Marseille (Jazzbook/Jazz Village)—Meanwhile, at the opposite end of the age spectrum, Ahmad Jamal is 87 years old, which means he’s three years away from being a nonagenarian. Paradoxically, he has in recent years sounded younger with age; more energetic and adventurous than he did back in the 1950s when he was wowing Chicago’s Pershing nightclub with his variations on “Poinciana.” His late-winter resurgence continues on this session with drummer Herlin Riley, bassist James Cammack and percussionist Manolo Badrena. His cleverness, whose flamboyance at one time annoyed the purists, has acquired keener, rougher edges on such tunes as “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child” and “Autumn Leaves,” the latter of which is a clinic on how a pianist and a rhythm session contain and release tension like dancers working within a narrow space. His timing and poise as leader and soloist have likewise sharpened, especially on his original compositions, “Pots En Verre,” “Baalbeck” and the title tune, given three variations here; first as a straight-ahead instrumental, then with a spoken version (by Abd Al Malik) and a ballad rendering (Mina Agossi) of Jamal’s French-language lyrics – which, by the way, are also pretty deft for a man of his advanced years. But who’s counting anyway? I’m going to predict that, by his 90th birthday in 2020, he’ll still be playing keep-away games with space and time on his piano and keeping his bass-drum tandems on their toes. Anybody want to bet against me? Or him?

3.) Steve Coleman’s Natal Eclipse, Morphogenesis (PI) – I’m resisting the temptation to label what Coleman’s been doing these last few years as an ongoing biological experiment. That would make it sound clinical and the music he and his various ensembles have recorded is anything but. Functional Arrythmias (2013) dealt with cardiovascular matters while Synovial Joints (2015) dared you to imagine knees, elbows, shoulders and legs accommodating themselves to whatever the music, organically conceived and arranged into being, was willing them to do. This time, the shape-shifting dynamics of Coleman’s approach is geared towards movement, core, tactics, kinesis and thrust; in other words, martial arts, specifically boxing. (You heard.) Thus the orchestrations have more density and drive, which makes this album at once more inscrutable and more accessible than its immediate predecessors. Jonathan Finlayson’s trumpet shows greater range of expression even when flying in close formation with Coleman’s alto saxophone. Jen Shyu’s voice returns to the mix while pianist Matt Mitchell, drummer Greg Chudzik, tenor saxophonist Maria Grand, violinist Kristin Lee and percussionist Neeraj Mehta all work together to create an collective entity of sound and rhythm you could use to prepare for any bout you have on the schedule, metaphorical or otherwise. Since these releases seem timed for every two years, I’m guessing Coleman and crew have another inquiry due in 2019. Is it possible, doctor, that…the human brain could be next on his agenda? (Egad!)

4.) Vijay Iyer Sextet, Far From Over (ECM) – “Down to the Wire,” “Into Action,” “Wake,” “End of the Tunnel”…The titles alone are challenges hurled into the Whirlwind of Now, especially the title track, which pulses throughout like a urgent telegraph message seeking a way out of the whatever it is we’ve been going through for (at least) the last year. Iyer, having done everything with the piano trio short of equipping it with double jet packs and a hood ornament, takes the wheel of this super-powered ensemble and comes perilously close to redefining the horns-rhythm-section paradigm. Pianist Iyer, bassist Stephan Crump and drummer Tyshawn Sorey lay down a sweet, spongy groove for “Nope” that gives the front line of alto saxophonist Steve Lehman, tenor saxophonist Mark Shim and horn master Graham Haynes lots of room to leap with controlled abandon. Electronics are deployed with discretion and purpose on the aforementioned “End of the Tunnel” while “Down to the Wire’s” overlapping riffs and steel-mesh polyrhythms exemplify the band’s breakneck intensity as does the lyrical fire shooting out of that elite horn section. Even when in relative reflection (“For Amiri Baraka”), the album seethes and goads its listeners to lean in and press forward into whatever trials lay ahead. We should probably take a hint from the way these guys go all out on these tracks: That our only way out of this mess may be us.

5.) Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis, The Music of John Lewis (Blue Engine) — Wynton Marsalis wasn’t the first musician to merge classical aspirations with jazz performance. Neither was John Lewis. But Lewis (1920-2001), who led the epochal Modern Jazz Quartet for roughly half his life, helped define by the middle of the last century a useable tradition within jazz music that could draw extensively upon its own heritage (blues, bop, swing and such) while establishing communion with baroque, romantic, impressionist and other genres linked to Europe. This legacy is vast and enduring enough to affect most of the jazz music written today, including most, if not all of the music represented on this list. Marsalis, especially, knows how much the very notion of Jazz at Lincoln Center, and jazz repertory in general, owes to Lewis and this tribute, recorded four years ago at Rose Hall, is an institution’s deeply-felt and elegantly-framed expression of gratitude. Marsalis, as ever, is the emcee-impresario as well an occasional soloist. But at center stage for this show is pianist Jon Batiste, a couple years before becoming nationally known as Steven Colbert’s “Late Show” bandleader-collaborator-egger-on. He proves an insightful surrogate for Lewis’ own inventions on such timeless pieces as “2 Degrees West, 3 Degrees East,” “Two Bass Hit” and (of course) “Django.” The concert’s revelations come in the orchestra’s renditions of themes taken from MJQ’s 1962 masterwork, The Comedy. That suite sustained the most knocks at the time from jazz peeps who believed Lewis was bowing too low to the European masters. But the orchestra, using a score adapted for big band by David Berger, makes the whole apparatus swing hard without in any way mitigating its surging romanticism. If I may partake of a quibble: The lovely “La Cantatrice” is rendered in these settings without a vocal proxy for the young Diahann Carroll, who sang this aria with the quartet on the Atlantic album. If the LCJO repeats this segment of the MJQ experiment, I know just the singer for the job. (Again, see Number 1 on this list).

6.) Matt Wilson, Honey and Salt: Music Inspired by the Poetry of Carl Sandburg (Palmetto) – Coming across this homage to the First Jazz Poet is like wandering into a neglected corner of one’s attic and stumbling into these motley contraptions that, with a little oil in their wheels and cleaning fluid in their cogs, can still whirr, hum and beguile. Drummer-bandleader-composer Wilson comes by his devotion legitimately, having hailed from the same Knox County, Illinois birthplace as Sandburg and been distantly related to boot. He’s been touring with his Carl Sandburg project for a few years now and has now yielded a cozy, colorful quilt of Sandburg-related instrumentals, songs and readings that constitute one of the precious few times that a jazz-poetry synthesis has worked so well. (Hell, worked. Period.) With Ron Miles on trumpet, Jeff Lederer on reeds, Martin Wind on bass and Dawn Thomson on guitar and lead vocals, Wilson provides deceptively simple frameworks, rhythmically and otherwise, for a Sandburg cornucopia (never has the word seemed more appropriate): A loping shuffle for “Soup”; an indigo-blue slow jam for “Night Stuff” (with Miles in top form) and a moody prairie lament for “Bringers” (“…of dawn and dusk and dreams…”). Even more intriguing is the interplay of the music with the poems as read by such notables as Jack Black (“Snatch of Slipshod Jazz”), Carla Bley (“To Know Silence Perfectly”), Rufus Reid (“Trafficker”), John Scofield (“We Must Be Polite”) and Sandburg himself, whose recital of “Fog,” where most of us first learned about metaphor in grade school, is stretched and elaborated upon by Wilson’s trap set. Is it possible for a jazz album to restore a literary reputation? I can’t say, but I do know when I hear the group join their voices on Sandburg’s “Choose” – “The single clenched fist lifted and ready/Or the open asking hand held out and waiting/Choose/For we meet by one or the other” – it feels very much as though these poems, their author and this project have arrived in our midst exactly when we need them most.

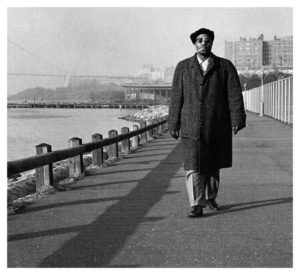

7.) Wadada Leo Smith, Solo: Reflections & Meditations on Monk (TUM) I’ll repeat here what I said two months ago: At age 75, Smith is enjoying a bountiful winter of recognition for his life’s work as trumpeter, composer and bandleader, creating fresh contexts for orchestrated jazz and delivering plaintive, ruminative yet remarkably agile narratives on his horn. His liner notes acknowledge his considerable debt to Monk, “an inspiration that arcs straight across the structured invisible world.” Smith’s own art, whether alone or in groups, uses intervals as nimbly as the master. In his own renditions of “Ruby, My Dear,” “Reflections,” “Crepuscule with Nellie” and “Round Midnight” (all of which dare the bold and the thoughtful to bring their “A” Game), Smith seems to know precisely how to sustain spaces between phrases and, more important, when to come in hard, when to use stealth – and, in the case with “Nellie,” when to let its essential form do most of the work. He rounds out the album with original pieces, a couple of them stimulated by visual depictions of the pianist at work (“Monk and his Five-Point Ring at the Five Spot Café,” “Adagio Monk, the Composer in Sepia – A Second Vision”) and another, intriguingly speculative narrative (“Monk and Bud Powell at Shea Stadium – A Mystery”). Generations of jazz musicians have brought their adorations of Monk to his legacy’s front door. I doubt there is any other musician alive who could have presented anything as austere, adventurous and challenging as Smith’s recital.

8.) Miguel Zenon, Tipico (Miel Music) – The title of the first track, “Academia” sounds vaguely like a threat, especially since it was apparently inspired by Zenon’s interaction with his students at the New England Conservatory of Music. But it’s a buoyant, effervescent take, setting you up for similarly joyful interactions to come. Zenon has in the past organized his albums around specific themes and narratives connected to his Puerto Rican heritage. But this time, he intends nothing more than a celebration of his 15-year affiliation with the rest of his quartet (pianist Luis Perdomo, bassist Hans Glawisching and drummer Henry Cole). What results is hardly academic, but you could learn a lot from the way Zenon’s alto sax communicates with the other instrumentalists. On “Cantor,” for instance, Glawisching and Perdomo lay down a spectral path for Zenon to soar, hover and gradually to create spiraling patterns whose intricacies sneak up on you. The title track evokes a whole subcontinent of rhythmic and melodic influences, galvanized by the quartet’s collective sway and swagger. Zenon’s intelligence and authority are asserted as definitively as on his previous albums. But this time, there’s a relaxed open-heartedness shared by all the musicians, whose only imperative is to make it all move at different tempos (tempi?) in beauty and mystery. Zenon’s playing, at least to these ears, has never sounded as frisky or as limpid as it does here.

9.) David Weiss & Point of Departure, Wake Up Call (Ropeadope) – Weiss, as he’s proven with all his varied ensembles (including this one), knows his way around the repertoire of the 1960s. He also is unapologetically drawn to the possibilities opened up by jazz-fusion of the 1970s and he’s apparently determined to help finish, or resolve, what those fusion artists started. The Point of Departure outfit is heard here in the kind of transition that jazz itself was a half-century ago as electronics seeped into hard bop’s domain. Only the album’s midsection, “Unfinished Business,” retains tenor saxophonist J.D. Allen and guitarist Nir Felder from the ensemble’s previous incarnation. For the rest, trumpeter-leader Weiss ups the ante by using two guitarists: Travis Reuter and Ben Eunson while Myron Walden assumes the tenor sax chair. The combination jars at first, but only for a while. And the ensemble shows its tight-knit cohesion when it dives into amplified renderings of John McLaughlin’s “Sanctuary,” Joe Henderson’s “Gazelle” and Tony Williams’ “Pee Wee.” On “The Mystic Knights of The Sea,” drawn from Williams’ early 70s band, Lifetime, Weiss’ group shows that piece to be not too far removed conceptually from the Williams who played with Miles Davis’ legendary mid-60s quintet. Everybody involved is focused and engaged, but if this album has an emerging star, it’s drummer Kush Abadey, who powers this edition of “POD” with a ferocity that seems ballistic in execution. He must be destined for greater things because Han Solo, who knows a little something about hyper-drive, made what’s known as the “jazz face” when he saw Abedey flash leather not so long ago at Small’s jazz club. He wouldn’t be the first star Weiss helped propel into greater prominence. And he won’t be the last.

10.) Christian McBride Big Band, Bringin’ It (Mack Avenue) – I’ve always suspected that there have been two identities in pitched battle for bassist McBride’s Philly-forged soul, one side embodied by Ray Brown, the other by Bootsy Collins. In this setting, and likely in others yet to come, the two sides aren’t in conflict so much as in spirited negotiations for a workable, lasting truce. The first track, a backyard-party rouser titled “Gettin’ To It,” loosens your bow tie and gives your head a reason to do its version of the Madison, or maybe the Funky Chicken. The immediate follow-up, Freddie Hubbard’s “Thermo,” is a steady-rolling swinger that has little in common with the opener besides the airtight rhythm section (McBride, pianist Xavier Davis, drummer Quincy Phillips and guitarist Rodney Jones) along with fleet-footed soloing by trumpeter Freddie Hendrix and tenor saxophonist Ron Blake. McBride’s wide-screen arrangement of “I Thought About You” discloses his higher-ground ambitions for his large ensemble and the band, with trumpeter Brandon Lee’s solo leading the way, comes through impressively enough for you to hope McBride aims even higher. Talks will likely continue between the Brown and Bootsy sides and McBride is a wicked-smart mediator, though part of me wishes he’d let his Famous Flames side cut loose for just one more album. If it happens, I’m all for him. If it doesn’t, I still am.

HONORABLE MENTION: Craig Taborn, Daylight Ghosts, (ECM) Tyshawn Sorey, Verisimilitude (PI); Heads of State, Four in One (Smoke Sessions); Matthew Shipp Trio, Piano Song (Thirsty Ear); Fred Hersch, Open Book (Palmetto); Jane Ira Bloom, Wild Lines: Improvising Emily Dickinson (Outline); Ron Miles, I Am A Man (Yellowbird); Joey Alexander, Monk. Live. Trio! (Motema); Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis, Handful of Keys (Blue Engine)

BEST REISSUE/ARCHIVAL

1.) Thelonious Monk, Les Liasons Dangereuses 1960 (SAM)

2.) Bill Evans, Another Time: The Hilversum Concert with Eddie Gomez & Jack DeJohnette (Resonance)

3.) Ornette Coleman, Ornette at 12 & Crisis (Real Gone)

BEST DEBUT ALBUM

Jaimie Branch, Fly or Die (International Anthem LLC)

BEST LATIN ALBUM

Miguel Zenon, Tipico

HONORABLE MENTION: Baptiste Trotignon & Yosvany Terry, Ancestral Memories (Okeh)

BEST VOCAL

Cecile McLorin Salvant, Dreams and Daggers

HONORABLE MENTION: Dominique Eade & Ran Blake, Town and Country (Sunnyside); Sarah Partridge, Bright Lights & Promises: Redefining Janis Ian (Origin)