April 25th, 2014 — jazz reviews

On the occasion of what would have been Ella Fitzgerald’s 97th birthday, I’m posting this mildly-annotated tribute I wrote for Newsday shortly after she died in July, 1996. Some of the questions raised in this piece remain open, except for whether she matters to people today. She does.

SIXTEEN DAYS have passed since Ella Fitzgerald died, and I still find prevailing among people of several generations a deep sadness over the loss. There’s wistfulness about Fitzgerald’s passing. I can’t recall encountering so many people in so many places who have spontaneously expressed their sense of loss for a departed jazz-pop icon – and I don’t expect to hear as many until we say farewell to Sinatra. (NOTE: Two years afterward, we did — and I did.)

What makes such an outpouring of grief more remarkable is that Fitzgerald spent most of her last years in the shadows of public life, stripped of her eyesight and physical mobility by several bouts with diabetes-related illnesses. In 1993 both of her legs were amputated. This slow fade seemed crueler than someone of Fitzgerald’s majestic effervescence and unfailing grace deserved. Which, in the hearts of many, only magnified the poignancy of her death. Now that tears have begun to dry, it seems time to assess the Ella Fitzgerald legacy.

I’ve encountered at least one skeptic in recent days. The opinion of this educated fellow – an exception to the widespread sentiment toward Fitzgerald following her death – is that she is a candidate for the century’s most overrated jazz singer.

His reasons, roughly summarized: Don’t tell me how innovative she was as a scat singer! She did the same scatting on every song! Betty Carter is so much better! Ella was predictable by comparison! And don’t tell me she was a true artist! She was an entertainer at best! She never invested any song with true sensibility or meaning, like Billie Holiday! She just reached into the same bag of crowd-pleasing tricks. And you can’t deny that her vocal range wasn’t all that wide. She sounded like a little girl most of the time. People love that! No wonder she was popular! But greatness isn’t a popularity contest . . .

Well. Where does one begin to hack away at such ferocious revisionism? Probably by saying that none of his arguments are all that new.

I know this, because not so long ago I agreed with many of them, especially the stuff about Fitzgerald’s investing no true sensibility or meaning into a song. The technical proficiency that dazzled me as a child, the bubbly warmth she put forth in both her live and recorded performances seemed – as I grew older and compared her to other singers – to be manifestations of an emotionally evasive personality. Frequently, I wanted to shout back at the record player, “Come on, Ella! Give it up! Show us your scars!”

It didn’t help that there was much about her personal life that was mysterious, starting with her date of birth. (Though Fitzgerald’s age at the time of her death was reported by many to be 78, court records in her Newport News, Va., birthplace confirm that she was born April 25, 1917, making her a year older.) There was real drama in her meteoric rise from poverty to 1930s stardom with the Chick Webb orchestra, in her taking command of the band after Webb’s death and in her slow, steep ascension to international stardom. But if there was any trace of emotional tribulation or hardship that accompanied Fitzgerald on her life’s journey, forget about finding it in her music – or, for that matter, in anything written or published about her life. (British critic Stuart Nicholson’s 1993 biography, “Ella Fitzgerald,” available in DaCapo paperback, is the best available source – and even he had trouble breaking through the barrier of privacy that was diligently maintained by Fitzgerald practically to the very end.)

Fitzgerald’s limited vocal range is a point I’ll readily concede to our revisionist friend. I never quite bought the claims of those old Memorex recording-tape commercials that Fitzgerald could break a wine glass with the ballistic surge of her voice. Sarah Vaughan could, for sure. But Ella? Yes, she had perfect pitch, a clean, clear delivery and air-tight rhythmic control. But her voice never threatened the edges of outer space like that of a great soprano or contralto.

And so what? In jazz music, what matters is not what you bring to the table, but what you do with it when you arrive. Fitzgerald drew upon a seemingly inexhaustible supply of enthusiasm and ingenuity and, in the process, fashioned a persona that kept her concert audiences on the edge of their seats, wondering what turn of phrase or cheeky reference she’d throw out next. Such gifts, as critic Martin Williams once wrote, may belong more to melodrama than genuine tragedy. But not even Williams’ imperious standards could withstand the assaults of Fitzgerald’s dynamism.

“For me,” Williams wrote, “hers is the stuff of joy, a joy that is profound and ever replenished – perhaps from the self-discovery that, for all her equipment as a singer’s singer, she is absolutely incapable of holding anything back.” (Italics mine.) Even the “little girl” characteristics cited as grievances against Fitzgerald’s artistry can be used to support the case for her staying power.

As long as there is curiosity about the classic American popular song of the 20th Century, there will be listeners who want a singer who can convey that music with a child’s unadorned sense of discovery. Many of us who grew up loving the songs of Cole Porter, Jerome Kern, Rodgers and Hart and the Gershwins did so because of Fitzgerald’s inviting, affectionate and solicitous interpretations. Years from now, those songbooks will be consulted about the great songs the way the dictionary is used to look up words.

So while I once wondered about Fitzgerald’s depth of passion or range of resources, I now believe there is emotional transcendence to be found in her euphoric invention. (A memo to our revisionist friend: Ask Betty Carter sometime whether she thinks Ella is overrated. Chances are good she’ll tell you no . . . and then rip your head off for suggesting otherwise.) Yet, this virtue, along with many others, doesn’t account for the widespread lingering sadness that people feel about Fitzgerald’s departure.

So what does? Nostalgia? We’re getting warmer, but the word alone doesn’t quite fit. I suspect what we mourn is more than the loss of a singer. Fitzgerald’s death is just part of our steadily eroding connection with the very notion of song as an ordered pattern of melody, harmony, emotion and intellect, expressing who we are and how we feel at any given moment. Nowadays, just a heavy beat with a few vague chords seems enough to satisfy those who want emotional and physical release – or, worse yet, simple gratification.

When Ella Fitzgerald or, indeed, any other icon from a more romantic and optimistic era leaves us, we feel abandoned – and a little panicky. We look around and wonder who’s able to connect with our emotions as they deepen and ripen to uneasy maturity.

Meanwhile, we’ll have the imposing pile of recordings Fitzgerald left behind. We’ll lose ourselves in them over and over again, while harboring the suspicion that she may have taken all the depth and most of the possibilities of American pop music with her to the grave. I was wrong about Ella. I hope I’m wrong about this.

Copyright 1996 Newsday, Inc.

June 12th, 2013 — jazz reviews

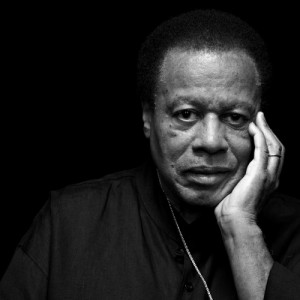

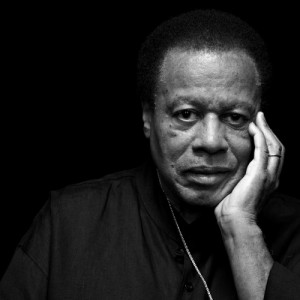

1.) During the one time I interviewed Wayne Shorter, I asked why no one had ever asked him to compose a film score. This set him off on an epic soliloquy on how male movie stars walk from Bogart, Gable and Cagney to Lancaster, McQueen and (I think) Poitier. He got up out of his chair and gave brief, impromptu imitations. He even brought Kirk Douglas into the discussion by which time he got me so caught up in whatever he was saying that I tried to bring such contemporary-cool avatars as Douglas’s son Michael and Denzel Washington into the mix (to little avail). He digressed into matters of posture, pace and the way people sway their arms in stride. It was enrapturing, frenzied and elliptical; like much of his music, only with words. I didn’t, couldn’t write any of it down because I knew I’d never get it in my paper. I wish I could find the tape, though. I also wish he’d answered my original question – and still wish that that somebody, anybody else would, too.

1.) During the one time I interviewed Wayne Shorter, I asked why no one had ever asked him to compose a film score. This set him off on an epic soliloquy on how male movie stars walk from Bogart, Gable and Cagney to Lancaster, McQueen and (I think) Poitier. He got up out of his chair and gave brief, impromptu imitations. He even brought Kirk Douglas into the discussion by which time he got me so caught up in whatever he was saying that I tried to bring such contemporary-cool avatars as Douglas’s son Michael and Denzel Washington into the mix (to little avail). He digressed into matters of posture, pace and the way people sway their arms in stride. It was enrapturing, frenzied and elliptical; like much of his music, only with words. I didn’t, couldn’t write any of it down because I knew I’d never get it in my paper. I wish I could find the tape, though. I also wish he’d answered my original question – and still wish that that somebody, anybody else would, too.

2.) In the summer of 2001, he appeared – materialized? – at New York’s JVC Jazz Festival in one of the first live appearances of the quartet that many now consider the best small combo in jazz. (This is by no means a unanimous opinion; more later about this.) So much time had passed since people heard him playing acoustic jazz with a rhythm section that there were several red-zone levels of anticipation for this show, the closing act of a three-tiered bill that, if memory served, included a crowd-pleasing Chick Corea set. The house fell in on him as soon as he walked on-stage. But the glow receded as soon as he started playing. He seemed reticent, even tentative, as if he were still hugging corners of the shadow-world in which he’d embedded himself for most of the previous decade. It wasn’t quite the rouser everyone in Avery Fisher Hall was amped for and one remembers how deflated even the most indulgent true believers looked as they filed out that night — though, to be fair, that acoustically-challenged venue may not have been the most ideal for a quartet seeking a détente between rumination and momentum.

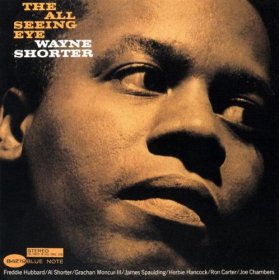

3.) On the other hand, what else DID they expect? A John Coltrane-style secular-mystical revival, radiant fire breathing and all? That’s not what you anticipate – or even desire – from Wayne Shorter, though he’s certainly proven himself capable of such incantatory drive. (I don’t know how many times I’ve played Juju among friends and found those unfamiliar with the album swear that it was Coltrane playing that tenor, even after I’ve told them otherwise.) Shorter, going all the way back to his mid-1960s tenure with Miles Davis (and more so with his Blue Note albums of that period) always connected with the writer within me. He had a distinctive, near-oblique narrative voice: lyrical, inquisitive, restless, but always with a solid harmonic foundation bracing his often-eccentric digressions. The sound of his saxophone didn’t swallow you whole as Coltrane’s could, but rather carried you along like a magical-realist storyteller. As with the best music of that era, Shorter’s playing and composing didn’t impose their mystique upon you so much as invite you to come up with your own poetic responses. George Harrison would have understood where Shorter was coming from – and for all I know, likely did.

4.) I just now remembered something else from that interview: His abiding interest in comic books and in one series in particular featuring a dauntless young aviator named “Airboy.” (There was one other hero whose name now escapes me. I’ve GOT to find that tape!) It occurred to me at that moment to ask why he never wrote a tune with “Airboy” as a title, but somehow we got caught up on another subject.

5.) As for writing a score for movies….what the hell. The way Hollywood is now, he’d be a lot better for them than they’d be to him. Best to make up your own movies in your head while listening to “Chief Crazy Horse” or “Mah-Jong” or “Schizophrenia” or “Over Shadow Hill Way” or “Calm” or “Face of the Deep” or “Deluge” or “The All-Seeing Eye” and…Know what? Even some of the titles, when you throw them in the air come across like some allusive, inscrutable and faintly volatile Shorter solo when they hit the page.

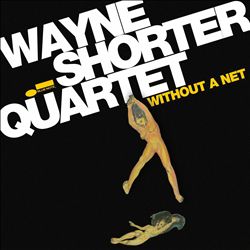

6.) So then…what about the other guys – Danilo Perez on piano, John Patitucci on bass and Brian Blade on drums? Do they and their leader deserve to be mentioned in the same breath as the Davis-Shorter-Hancock-Carter-Williams tandem – or any other classic small-jazz group that you can think of? Maybe it’s enough that Shorter always looks on-stage as if he’s overjoyed to be with them. I always had the feeling that from the start of their association, each member of the rhythm section was using his own resources to draw Shorter further out into the open. If their latest album, the aptly titled Without a Net (Blue Note) is any indication, they’re still tugging, coaxing and, especially in Blade’s case, shoving Shorter towards the deeper end of the pool. Often, it sounds as though he’s hanging back at the start, letting his fellas set the table before allowing whatever’s in his head seep or leap into view. Hence his off-the-cuff rendering of the “Lester Leaps In” theme that opens “S.S. Golden Mean,” which seems calculated to get Patitucci, Perez and Blade to ramp it up a little more. They do and this in turn gets Shorter to toss more angular shards of phrasing at unexpected times. (See what you do with this one! Wait! Think fast! I got another one.) Taking in all this freewheeling interplay is like making one’s way through a murder mystery written by a surrealist poet. There are enough familiar signposts of the genre to string you along, but the prose trips you up as often as the plot.

7.) On record, it’s engrossing; on-stage, it’s challenging, but no more so than a Bartok string quartet. (You’ll have plenty of opportunities to find out as the beginning of Shorter’s ninth decade is celebrated in live performance here and elsewhere throughout the year.) Still, many listeners coming with their own preconceived notions of what jazz is, or should be, find this quartet’s method too arbitrary and unfocused. Some might suspect the quartet’s colloquies are little more than expanded, busier editions of the airy, abstracted interplay in which Shorter and his old friend Herbie Hancock engaged with mixed results in their 1997 duet album, 1+1 (Verve).

8.) I’m nowhere near as negative, but I understand why others are. When Shorter edged his way back into full view less than twenty years ago, I hoped he’d carry with him some hooks and melodies evoking the familiar, relative solidity of “Speak No Evil” or “Adam’s Apple” – which, lest any of us forget, were considered pretty far out in their own time by those who left their hearts and heads with hard bop and cool jazz. It would seem that Shorter, whose place in history as a composer is safe and secure, now wants to find ways of inventing off the imperatives of a given moment, just as Miles Davis insisted on doing to the end. He’d just as soon share such moments with his team, the better to see where they can take him. I don’t mind the extra work they give me because as a listener, I’m taking the leap with them. True, I wouldn’t mind a net, or even a soft, wet towel at the bottom. But if “Airboy” can fly through the thickest, stickiest obstacles, Shorter believes we should at least try. You may come out the other end thinking bigger than you did before — or at least, more different.

December 19th, 2011 — jazz reviews

Before we get to this year’s Top Ten, some random thoughts: 2011 has been such a mean, tumultuous, uprooting year for me that it was a challenge to keep track of the latest recordings. With the year almost over, I’m factory-sealed certain that I’ve left several worthy candidates behind. See them? They’re glaring at me from behind, standing with hands on hips or waving at my dust trail as if to say, “What?”

Then again, I find myself wondering what the hell they’re doing there. Seems to me I heard at some point this fall that Termination Day for CDs is approaching even faster than one had been led to believe. If we want the latest Keith Jarrett or Aaron Neville, we need only reach into a cloud — a.k.a. THE Cloud — and snatch whatever track we want. I still can’t believe that’s all we’ll eventually be left with. But it’s what all the salespeople insist is happening and they’ve never lied to us before. Ever.

And yet, you’re all here, aren’t you? Even though I haven’t yet learned how to download album covers or to make the necessary links to specific tracks. Someday, maybe even next year, that’ll be in place. For now, some tough choices from a tough year…

1.) Sonny Rollins, “Road Shows Vol. 2” (Doxy) – The Greatest Live Act in Jazz, headlined by the Greatest Living Improviser, keeps rolling along, its every flourish and delicacy captured for what promises to be an epochal series of recordings from past and (one hopes) future concerts. This second installment’s tracks are just a year old, but you understand why they needed to be out there in a hurry. They celebrate the start of the Colossus’ ninth decade as observed in Japan and, most notably, at last September’s “Sonny Rollins @80” concert @ New York’s Beacon Theater. On that evening, the celebrant, leonine and fit, sounded frisky and responsive to the electricity of the moment, his furry tone combed to a bristly sheen. He brought out guitarist Jim Hall, his comparably indefatigable 1960s playmate (to dive into “In a Sentimental Mood,” of course) as well as trumpeter Roy Hargrove who, as with the leader, always brings his A-game in front of onlookers. This disc is the next best thing to having been there. Yet it still makes you wish you’d been able to share the audience’s excitement at seeing Ornette Coleman wander on-stage for a characteristically insurgent solo on “Sonnymoon for Two” wherein he lures the Colossus “outside” the regular changes for some buoyant give-and-take. If Rollins is now the de-facto king of whatever it is we mean when we talk about jazz, then this edition of “Road Shows” shows him to be a wise, benevolent ruler whose domain, however small it may seem to outsiders, feels accessible enough to meet your most urgent needs and expansive enough to contain multitudes.

2.) Ambrose Akinmusir, “When the Heart Emerges Glistening” (Blue Note) – Only four years removed from winning the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Competition, this 29-year-old trumpeter has delivered on his grand promise with an album of startling depth and range. Once you get past the challenges of pronouncing his intimidating surname (ah-kin-MOO-sir-ee) and of getting past the album’s knotty title, you’re free to acclimate with his big, brilliant sound or unravel the intricacies of his soloing – which, while layered with the trills, glissandos and arpeggios emblematic of the jazz trumpet’s heritage, share the probing detail and varied attack of sax icon Joe Henderson and of pianist (and album co-producer) Jason Moran. For all his agility and command, Akinmusire leans heavily on his band-mates (tenor saxophonist Walter Smith III, pianist Gerald Clayton, bassist Harish Raghavan and drummer Justin Brown); all of whom are worthy collaborators, collectively and individually. Word is out that these guys are all part of a big band that Akinmusire is leading. Can’t wait to hear what that’s like.

2.) Ambrose Akinmusir, “When the Heart Emerges Glistening” (Blue Note) – Only four years removed from winning the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Competition, this 29-year-old trumpeter has delivered on his grand promise with an album of startling depth and range. Once you get past the challenges of pronouncing his intimidating surname (ah-kin-MOO-sir-ee) and of getting past the album’s knotty title, you’re free to acclimate with his big, brilliant sound or unravel the intricacies of his soloing – which, while layered with the trills, glissandos and arpeggios emblematic of the jazz trumpet’s heritage, share the probing detail and varied attack of sax icon Joe Henderson and of pianist (and album co-producer) Jason Moran. For all his agility and command, Akinmusire leans heavily on his band-mates (tenor saxophonist Walter Smith III, pianist Gerald Clayton, bassist Harish Raghavan and drummer Justin Brown); all of whom are worthy collaborators, collectively and individually. Word is out that these guys are all part of a big band that Akinmusire is leading. Can’t wait to hear what that’s like.

3.) Noah Preminger, “Before the Rain” (Palmetto) – At age 24, Preminger, a front-rank tenor saxophonist on just his second album as a leader, plays ballads as if he were a seventy-something road-warrior. He already knows, on instinct, how to approach a melody from behind; where to hang the drapery on a chord change and when to gently pull it away. And he doesn’t seem in a hurry to disclose everything he knows, not even on his original compositions (the title track, “Abreaction,” “Jamie”) or on Ornette Coleman’s “Toy Dance.” As with Akinmusire, Preminger is blessed with a eerily compatible rhythm section of bassist John Herbert, drummer Matt Wilson and pianist Frank Kimbrough, who contributes a couple of his prodigious compositions (“Quickening,” “November”) to the cause. By the time this group gets to massage a sturdy war horse such as “Until the Real Thing Comes Along,” you’re utterly convinced that Preminger is the real thing – and that he’s coming along quite nicely.

3.) Noah Preminger, “Before the Rain” (Palmetto) – At age 24, Preminger, a front-rank tenor saxophonist on just his second album as a leader, plays ballads as if he were a seventy-something road-warrior. He already knows, on instinct, how to approach a melody from behind; where to hang the drapery on a chord change and when to gently pull it away. And he doesn’t seem in a hurry to disclose everything he knows, not even on his original compositions (the title track, “Abreaction,” “Jamie”) or on Ornette Coleman’s “Toy Dance.” As with Akinmusire, Preminger is blessed with a eerily compatible rhythm section of bassist John Herbert, drummer Matt Wilson and pianist Frank Kimbrough, who contributes a couple of his prodigious compositions (“Quickening,” “November”) to the cause. By the time this group gets to massage a sturdy war horse such as “Until the Real Thing Comes Along,” you’re utterly convinced that Preminger is the real thing – and that he’s coming along quite nicely.

4.) Allen Lowe, “Blues and the Empirical Truth” (Music & Arts) – Is it music or is it scholarship? Or musical scholarship? Is it criticism of the blues or just critical of them (or at least of what people say about them)? These and dozens of other questions aroused by “Blues and the Empirical Truth” are far more significant than any answers I or anyone else pretending to know more about music than Allen Lowe can cobble together. Lowe is a gnomic, compulsively idiosyncratic polymath who lives in Maine, plays a red-hot saxophone and has for years put together epic inquiries into the history and nature of American music and how it shapes – or doesn’t – the national character. On this three-disc set, recorded over a two-year period, Lowe arranges, composes and plays “inside” and “outside” jazz as well as such makeshift forms as neo-gutbucket-progressive-punk (at least that’s what I’m calling it for the moment.) He is backed by a typically eclectic guest list that includes guitarist Marc Ribot, pianist Matthew Shipp, trombonist Roswell Rudd and Lowe’s fellow musicologist Lewis Porter, contributing here and there on keyboards. Along the way, tribute is made to civil rights activists Pauli Murray and Ella Mae Wiggins, forgotten or obscure musicians such as saxophonist Dave Schildkraft and pianist Blind Tom Bethune and…Doris Day, who should have been invited to Portland to jam with this crowd; except you have to wonder what she would have made of a song list with such titles as “Speckled Shaw Crippled Pete Boogie,” “Blues in Transfiguration,” “Elvis Died With His Sins Intact,” “In a Harlem Ashram” and “(Bull Connor Sees) Darkies on the Delta.” Guess it doesn’t matter as long as no animals were harmed in the process.

4.) Allen Lowe, “Blues and the Empirical Truth” (Music & Arts) – Is it music or is it scholarship? Or musical scholarship? Is it criticism of the blues or just critical of them (or at least of what people say about them)? These and dozens of other questions aroused by “Blues and the Empirical Truth” are far more significant than any answers I or anyone else pretending to know more about music than Allen Lowe can cobble together. Lowe is a gnomic, compulsively idiosyncratic polymath who lives in Maine, plays a red-hot saxophone and has for years put together epic inquiries into the history and nature of American music and how it shapes – or doesn’t – the national character. On this three-disc set, recorded over a two-year period, Lowe arranges, composes and plays “inside” and “outside” jazz as well as such makeshift forms as neo-gutbucket-progressive-punk (at least that’s what I’m calling it for the moment.) He is backed by a typically eclectic guest list that includes guitarist Marc Ribot, pianist Matthew Shipp, trombonist Roswell Rudd and Lowe’s fellow musicologist Lewis Porter, contributing here and there on keyboards. Along the way, tribute is made to civil rights activists Pauli Murray and Ella Mae Wiggins, forgotten or obscure musicians such as saxophonist Dave Schildkraft and pianist Blind Tom Bethune and…Doris Day, who should have been invited to Portland to jam with this crowd; except you have to wonder what she would have made of a song list with such titles as “Speckled Shaw Crippled Pete Boogie,” “Blues in Transfiguration,” “Elvis Died With His Sins Intact,” “In a Harlem Ashram” and “(Bull Connor Sees) Darkies on the Delta.” Guess it doesn’t matter as long as no animals were harmed in the process.

5.) Muhal Richard Abrams, “SoundDance” (Pi) – Just so you know, Sonny Rollins isn’t the only octogenarian legend who’s still getting the job done. Abrams, the peerless pianist-composer who co-founded the legendary Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) nearly 50 years ago, marked his own ninth decade by engaging in colloquies of such breadth and magnitude that they each needed their own disc. One of these is a dialogue with tenor saxophonist Fred Anderson that took place in October, 2009, a year before the latter’s death, though it’s a strain to detect signs of sagging energy in his playing. Both Abrams and Anderson seem energized by the task of extending or enhancing each other’s thoughts and even listeners resistant to free-form improvisation won’t miss a beat (so to speak). A year later, Abrams engaged in a sonic pas de deux with fellow innovator, author and AACM veteran George Lewis, who brought both his trombone and his laptop to the party. These two masters of orchestration create intricate, spiraling patterns that are at once imposing and puckish. You can wander in and out of their gallery of sound and find something strange, shiny and, in a peculiar way, companionable.

5.) Muhal Richard Abrams, “SoundDance” (Pi) – Just so you know, Sonny Rollins isn’t the only octogenarian legend who’s still getting the job done. Abrams, the peerless pianist-composer who co-founded the legendary Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) nearly 50 years ago, marked his own ninth decade by engaging in colloquies of such breadth and magnitude that they each needed their own disc. One of these is a dialogue with tenor saxophonist Fred Anderson that took place in October, 2009, a year before the latter’s death, though it’s a strain to detect signs of sagging energy in his playing. Both Abrams and Anderson seem energized by the task of extending or enhancing each other’s thoughts and even listeners resistant to free-form improvisation won’t miss a beat (so to speak). A year later, Abrams engaged in a sonic pas de deux with fellow innovator, author and AACM veteran George Lewis, who brought both his trombone and his laptop to the party. These two masters of orchestration create intricate, spiraling patterns that are at once imposing and puckish. You can wander in and out of their gallery of sound and find something strange, shiny and, in a peculiar way, companionable.

6.) Craig Taborn, “Avenging Angel” (EMI) – A title of one track could easily apply to most of the others: “A Difficult Thing Said Simply.” Taborn, who owns one of the most eclectic curriculum vitae in contemporary music (Tim Berne AND James Carter?), approaches the art of solo jazz piano as if he were translating complex code from a distant star. Often, he binds the information in tightly-wound chords struck down as if on anvils to forge unusual shapes. At other times (the aptly-named “Glossolalia”), he lets things twirl in the air like dazed, tiny phantasms squeezed out of an overcrowded basement. As with the early work of Keith Jarrett, Taborn is prone to lean to too hard on a riff, but (again, as with Jarrett) the digging can occasionally lead to an illuminated strike. In what’s been a vintage year for solo jazz piano discs (see the honorable-mention list below), this stood out for one simple reason: It sounded the most different from what its genre had yielded before.

6.) Craig Taborn, “Avenging Angel” (EMI) – A title of one track could easily apply to most of the others: “A Difficult Thing Said Simply.” Taborn, who owns one of the most eclectic curriculum vitae in contemporary music (Tim Berne AND James Carter?), approaches the art of solo jazz piano as if he were translating complex code from a distant star. Often, he binds the information in tightly-wound chords struck down as if on anvils to forge unusual shapes. At other times (the aptly-named “Glossolalia”), he lets things twirl in the air like dazed, tiny phantasms squeezed out of an overcrowded basement. As with the early work of Keith Jarrett, Taborn is prone to lean to too hard on a riff, but (again, as with Jarrett) the digging can occasionally lead to an illuminated strike. In what’s been a vintage year for solo jazz piano discs (see the honorable-mention list below), this stood out for one simple reason: It sounded the most different from what its genre had yielded before.

7.) Youn Sun Nah, “Same Girl” (ACT) – Didn’t know a thing about her when this disc slipped into in my mailbox earlier in the year. After one track, I found myself asking, “Where has she been all my life?” (In Europe, apparently, where this album was first released last winter.) She is steeped in the French chanson tradition, but as with the most interesting singers beyond the boomer generation – Is she really 42? – she’s willing to try anything from Broadway (“My Favorite Things”) to Brazil (“Song of No Regrets”), from the folk music of her native Korea (“Kangwondo Aririang”) to the mellow sounds of Metallica (“Enter Sandman”). And she can scat real good, too, as proven on the quiet-fire “Breakfast in Baghdad.” The minimalist backing she gets from guitarist Ulf Wakenius, bassist-cellist Lars Danielson and percussionist Xavier Desandre lets her rangy, limber voice roam, run and leap about at will, even when the material is dipped in deep blue. Nothing seems to scare or stop her. Good as this disc is, it makes you wish she’d dare even more.

7.) Youn Sun Nah, “Same Girl” (ACT) – Didn’t know a thing about her when this disc slipped into in my mailbox earlier in the year. After one track, I found myself asking, “Where has she been all my life?” (In Europe, apparently, where this album was first released last winter.) She is steeped in the French chanson tradition, but as with the most interesting singers beyond the boomer generation – Is she really 42? – she’s willing to try anything from Broadway (“My Favorite Things”) to Brazil (“Song of No Regrets”), from the folk music of her native Korea (“Kangwondo Aririang”) to the mellow sounds of Metallica (“Enter Sandman”). And she can scat real good, too, as proven on the quiet-fire “Breakfast in Baghdad.” The minimalist backing she gets from guitarist Ulf Wakenius, bassist-cellist Lars Danielson and percussionist Xavier Desandre lets her rangy, limber voice roam, run and leap about at will, even when the material is dipped in deep blue. Nothing seems to scare or stop her. Good as this disc is, it makes you wish she’d dare even more.

8.) Bill Frisell, “Sign of Life” (Savoy) – At its most inquisitive and unfettered, Bill Frisell’s music can be as evocative of the “the old, weird America” as Bob Dylan’s 1967 basement tapes. (Come and get me, Greil Marcus!) He has a boho-folk artist’s affinity for both the pastoral and the abstract. Beneath even his most glowing, spacious-skies landscapes, there are flickering shadows and misshapen objects that don’t distort the view, but are blended to make a slightly cockeyed, but still arresting picture, “Sign of Life,” performed by his 858 Quartet of violinist Jenny Schienman, violist Eyvind Kang and cellist Hank Roberts, is his best-realized sound painting since 2001’s “Blues Dream,” whose noir-ish cloaking devices I still appreciate, even if others didn’t. This is a sunnier compound of motifs and riffs that give off an aura of mystery, even danger – especially when the irrepressible Scheinman starts throwing paraphrases and adornments like left jabs. It’s clearer than ever that with both this disc and the John Lennon tribute released in the same year, Frisell can’t be stopped – or even contained. Only sampled – and what would NPR do for filler between news stories if his music weren’t around?

8.) Bill Frisell, “Sign of Life” (Savoy) – At its most inquisitive and unfettered, Bill Frisell’s music can be as evocative of the “the old, weird America” as Bob Dylan’s 1967 basement tapes. (Come and get me, Greil Marcus!) He has a boho-folk artist’s affinity for both the pastoral and the abstract. Beneath even his most glowing, spacious-skies landscapes, there are flickering shadows and misshapen objects that don’t distort the view, but are blended to make a slightly cockeyed, but still arresting picture, “Sign of Life,” performed by his 858 Quartet of violinist Jenny Schienman, violist Eyvind Kang and cellist Hank Roberts, is his best-realized sound painting since 2001’s “Blues Dream,” whose noir-ish cloaking devices I still appreciate, even if others didn’t. This is a sunnier compound of motifs and riffs that give off an aura of mystery, even danger – especially when the irrepressible Scheinman starts throwing paraphrases and adornments like left jabs. It’s clearer than ever that with both this disc and the John Lennon tribute released in the same year, Frisell can’t be stopped – or even contained. Only sampled – and what would NPR do for filler between news stories if his music weren’t around?

9.) Miguel Zenon, “Alma Adento: The Puerto Rican Songbook” (Marsalis Music) – Not only was this the year’s best Latin jazz album, it was also among the more inspired examples of that overpopulated subgenre, the tribute album. Zenon’s homage isn’t to a single artist or composer, but to the men and women who wrote the classic pop tunes of his native land. He and arranger Guillermo Klein practically reinvent crooner Bobby Capo’s “Incomprendido” as a slow-drying lament. Conversely, Rafael Hernandez’s “Silencio,” revived by the “Buena Vista Social Club” some years back, is given a near-chimerical, tempo-shifting transformation. The centerpiece, literally and figuratively, comprises two pieces by Sylvia Rexach: the title track and “Olas y Areenas,” both of which are treated by Zenon and Klein with passionate intensity and solicitous intelligence. Zenon may sometimes risk going overboard with his ambition and with his playing, but that’s part of the attraction. And if his alto-sax soars like a rocket plane, he’s becoming more adroit at gliding to pinpoint landings. .

9.) Miguel Zenon, “Alma Adento: The Puerto Rican Songbook” (Marsalis Music) – Not only was this the year’s best Latin jazz album, it was also among the more inspired examples of that overpopulated subgenre, the tribute album. Zenon’s homage isn’t to a single artist or composer, but to the men and women who wrote the classic pop tunes of his native land. He and arranger Guillermo Klein practically reinvent crooner Bobby Capo’s “Incomprendido” as a slow-drying lament. Conversely, Rafael Hernandez’s “Silencio,” revived by the “Buena Vista Social Club” some years back, is given a near-chimerical, tempo-shifting transformation. The centerpiece, literally and figuratively, comprises two pieces by Sylvia Rexach: the title track and “Olas y Areenas,” both of which are treated by Zenon and Klein with passionate intensity and solicitous intelligence. Zenon may sometimes risk going overboard with his ambition and with his playing, but that’s part of the attraction. And if his alto-sax soars like a rocket plane, he’s becoming more adroit at gliding to pinpoint landings. .

10.) Evan Christopher, “Remembering Song” (Arbors) – If you paid close attention to “Treme” this year…no, wait. I have to digress just a little here. I’ve been hearing fans of “The Wire” complain that they find “Treme” too slow, too dense and not as – what? – urgently engrossing as its predecessor. I am compelled to remind these folks that it took at least three seasons for “The Wire” to find a following. And that only when it was nearly over did people begin thinking of it as a “classic.” So though it’s no longer fashionable in pop-culture circles to counsel patience, call me unfashionable. Watch and wait…Anyway, if you did pay close attention to “Treme,” you probably saw Christopher jamming with Tom McDermott and the luminous Lucia Micarelli on Scott Joplin’s “Heliotrope Bouquet.” He has been one of Crescent City’s most lyrical and stalwart clarinetists and this love letter to his adopted hometown is both a wistful lament for the unshakable legacy of Katrina and a bittersweet celebration of the spirit that refuses to wither or retreat from that legacy. His original compositions – e.g., “The River by the Road”, “You Gotta Treat It Gentle” – show that he’s not trying to reinvent tradition, but fulfill its demands. Sometimes, you don’t need to listen to something that changes the world. Easing its pain is enough. And for me, this year especially, it was more than enough.

10.) Evan Christopher, “Remembering Song” (Arbors) – If you paid close attention to “Treme” this year…no, wait. I have to digress just a little here. I’ve been hearing fans of “The Wire” complain that they find “Treme” too slow, too dense and not as – what? – urgently engrossing as its predecessor. I am compelled to remind these folks that it took at least three seasons for “The Wire” to find a following. And that only when it was nearly over did people begin thinking of it as a “classic.” So though it’s no longer fashionable in pop-culture circles to counsel patience, call me unfashionable. Watch and wait…Anyway, if you did pay close attention to “Treme,” you probably saw Christopher jamming with Tom McDermott and the luminous Lucia Micarelli on Scott Joplin’s “Heliotrope Bouquet.” He has been one of Crescent City’s most lyrical and stalwart clarinetists and this love letter to his adopted hometown is both a wistful lament for the unshakable legacy of Katrina and a bittersweet celebration of the spirit that refuses to wither or retreat from that legacy. His original compositions – e.g., “The River by the Road”, “You Gotta Treat It Gentle” – show that he’s not trying to reinvent tradition, but fulfill its demands. Sometimes, you don’t need to listen to something that changes the world. Easing its pain is enough. And for me, this year especially, it was more than enough.

HONORABLE MENTION:

1.) Gonzalo Rubalcaba, “Fe Faith” (5Passion)

2.) Matthew Shipp Trip, “The Art of the Improviser” (Thirsty Ear)

3.) Larry Goldings, “In My Room” (BFM)

4.) Charles Lloyd & Maria Farantouri, “Athens Concert” (EMI)

5.) Terrell Stafford, “This Side of Strayhorn (MaxJazz)

BEST NEW ARTIST

Chris Dingman, “Waking Dreams” (Between Worlds Music)

BEST VOCAL

Youn Sun Nah, “Same Girl” (see above)

BEST LATIN ALBUIM

Zenon, “Alma Adento: The Puerto Rican Songbook” (see above)

BEST REISSUE

Julius Hemphill, “Dogon A.D.” (Arista/Freedom) HONORABLE MENTION: Bill Dixon Orchestra, “Intents and Purposes” (RCA/Dynagroove)