THE MOVIE

Before she began directing films, Ava DuVernay publicized them – and was very good at her work. No surprise then that her adaptation of A Wrinkle In Time is, at the very least, a triumph of promotion. She was all-but-unavoidable on media outlets leading up to the movie’s release — and she’s still selling the movie even while it’s playing in front of you. The theatrical screening I saw opens with a message from DeVernay welcoming the audience, very much in the manner of Disney’s vintage TV anthology series Wonderful World of Color whose weekly offerings often began with Uncle Walt himself handling the introductions to whatever story or animated mélange would ensue over the next hour.

DuVernay’s Wrinkle In Time is a movie that continues to promote itself throughout. Almost every character in the movie is in the act of persuasion whether it’s Alex Murry (Chris Pine), the astrophysicist-dad obsessed with finding a means of “shaking hands with the universe” through psychic dimensional travel, his precocious young son Charles Wallace Murry (Deric McCabe) who somehow seems to know where and how to find his dad who went missing somewhere in the cosmos and the trio of spectral women (Oprah Winfrey, Reese Witherspoon, Mindy Kaling) who are trying to convince Charles Wallace’s implacable, mercurial older sister Meg (Storm Reid) that they are best equipped to lead the way past the dark, insidiously transient cosmic evil – Camazotz– that threatens to swamp everything in dread and rage. The movie sidesteps the novel’s religious underpinnings to promote a broader, more secular means of transcendence: Be brave, be daring, be empathetic, be a “warrior” for peace, love and understanding. etc. The lyrics to Earth, Wind and Fire’s “Shining Star” just about cover it and the anthem’s forty-plus years of existence may account for its being kept off the movie’s pop-loaded soundtrack.

If the overall spirit of DuVernay’s movie intends to prod its audiences to buy into what its selling, then most of its critics thus far are like Meg: grouchy, withholding and not terribly happy with the terrain. The Wall Street Journal’s Joe Morgenstern characterized DuVernay’s Wrinkle as “a magical mystery tour minus the magic and mystery” while New York magazine’s David Edelstein found the movie’s gaudy visual effects suffused with earnest talk of self-fulfillment and uplift adding up to little more than “a transcendental guidance counselor’s movie.” Even some of the more positive reviews, all of which laud the movie’s big heart and open mind, were muted; Richard Brody of the New Yorker thought the movie captured the story’s “sense of exhilaration and wonder” while lamenting that the script “eliminates the most idiosyncratic aspects of the novel.”

Brody, by the way, is so taken with the novel after reading it as an adult that he wishes he’d come across it earlier in life. He’s not the only one.

THE BOOK

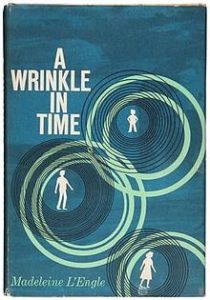

The copyright year is 1962. This would have placed me somewhere between nine and ten years old when A Wrinkle In Time was published. I might have been a shade too young, then, to easily connect with all the references made to tesseracts and other matters related to numbers and physics. I say “maybe” because in that year especially I was deeply invested in space travel and, by extension, in the possibilities of inter-dimensional travel.

Such interests, however, refused to keep pace with my affinity for what was then known as arithmetic. Both parents and teachers were at a loss to figure out how this disparity could be reconciled, especially in what was then known as junior high school. (Question for Further Study: Is boredom with school a requisite for underachievement? Discuss – and try to keep up with the rest of the class.)

Probably, then, not that year; but more likely the next couple of years when my solitary romance with time and space only intensified would have yielded more fertile ground for my fascination with Meg and her travels.

More likely, it would have been Meg’s travails that could have drawn me into the center of Madeleine L’Engle’s wheelhouse. By 1965, I would have been the same age as Meg and, thus, better able to relate to her as someone who, like me, had a head that was way too big for the rest of her body; someone who was also spectacularly uncoordinated, socially awkward and prone to wildly annoying behavior to overcompensate for low self-esteem.

The older person I am now reads L’Engle’s breakthrough novel far removed from the emotional cacophony of adolescence and assesses it as the hypothetical outcome of an Italo Calvino’s spin on an L. Frank Baum story idea as rewritten by Rod Serling – which is in no way a dismissal. In fact, one wishes Serling could have written as tautly as L’Engle does without shortchanging his patented sentiment.

Still, in the end, I don’t really know whether reading Wrinkle would have made much of a difference when I was Meg’s age because by that time, other fantasy authors with an older demographic (Bradbury, Sturgeon, Beaumont) were pulling me away from the YA label in libraries; so far away, by then, that it’s likely I would have thought the book too light and airy for the tougher, more lyrical things I was dipping into by Grade 7. But if the multi-cultural casting has done anything at all, it’s made me wonder how it would have affected my own adolescent conduct. Likely such questions would never have occurred to me if DuVernay hadn’t had a say in such casting.

That said…

THE MOVIE, AGAIN

To sum up my own apprehensions going in: I thought it was the most amazing luck that Ava DuVernay decided not to direct Black Panther because I don’t think she’s as good as others believe/hope she is. I supported Selma not because I thought it was great filmmaking (it wasn’t), but because it was necessary to have a movie that prominently placed its black characters as actors in their own deliverance as opposed to just about EVERYTHING of its kind made and distributed by Hollywood beforehand. I was also disappointed by The 13th because I thought it was more of a big fire-breathing billboard populated by talking heads than a documentary that made the necessary deep dives into the political intricacies behind crime bills & other initiatives that made “The New Jim Crow” possible.

She’s better here, but as with Selma the actors save her bacon, especially Ms. Reid, who holds together this thing pretty much on her own and is, I think, a real find; almost as good in her way as Mary Badham was in To Kill a Mockingbird. But Robert Mulligan was a more adroit director of kids than just about anybody who was a better director of movies than he was (if that makes any sense) and, from the way she directs the other kids, DuVernay is no threat to that reputation. Directing McCabe’s Charles Wallace, especially, requires the kind of imaginative approach to human behavior that DuVernay does not have at her disposal. If she had, she’d have dodged the trouble she’d gotten into over her characterization of LBJ in Selma because she’d have better apprehended the full Brobdingnagian complexity of Lyndon B’s personality.

Also for all her engagement with special effects, she doesn’t seem to know how to travel with them. That whole set piece where the kids are riding on the transmogrified back of Witherspoon’s Mrs. Whatsit (or was it Whosit? I lose track) goes nowhere except around the field as if Disney were already planning the ride for one of their theme parks.

Finally, I still can’t quite get over that introduction where DuVernay tells you not only what you’re going to see, but also how you’re supposed to feel at the end of it. This is altogether appropriate for a 50th anniversary of a restored classic. But this is neither an anniversary nor (really) a classic

AND YET…

For all my misgivings, I also understand that this movie isn’t made for me, but for every pre-teen who somehow feels ill at ease under their skins. Which is, last I checked, pretty much all of them. I am hearing of large groups of young people, most of them girls, who leave the movie with moist faces and glistening eyes. I may feel let down by this Wrinkle, but clearly they aren’t. If this is, for many of them, their first encounter with this species of science fantasy, then good on them and the grownups to take them to see it if it leads them to Bradbury, Sturgeon, Richard Matheson, even Phillip K. Dick, though if it were my pre-teen, I might tell her to wait just a little bit for that one.

AND SO…?

As of last weekend, Wrinkle in Time made up little more than half of its $103 million budget. This is leading some to say the “F” word (“flop” or “failure,” depending), though I think it’s still too early. There’s always the possibility that, as with most such movies with very tight close-ups stacked like cordwood, the smaller screen may be a hospitable place for DuVernay’s Wrinkle. Until that happens, let’s, shall we, stop comparing this to that other Disney-produced fantasy-adventure directed by an African-American. Neither Black Panther nor A Wrinkle In Time should be viewed as ultimate referenda on the economic efficacy of black American filmmaking. Things may have changed as much as Panther’s success indicates. But life goes on and memories are short. Unless, that is, you’re an impressionable 9-12-year-old whose horizons need raising. She can – and likely will – do far worse than take Wrinkle into her heart.