March 3rd, 2023 — movie reviews

The 2023 Oscar ceremonies bear down on us all like a vacant, runaway bus on an oil-slicked interstate. And yet, people still can’t stop nattering about what happened at the 2022 ceremonies, when somebody’s husband got so mad at somebody else’s bad joke at her expense that he bitch-slapped that somebody else while ABC did its gosh-darndest to keep us from seeing it happen. Now the Motion Picture Academy of Arts & Sciences have assembled a “crisis team” to make sure it doesn’t happen again. Too bad. They could use the ratings. And they know it.

For yet another year, the Academy Awards stagger into view beneath a fog of uncertainty as to whether they should continue to exist at all. In a recent interview, erstwhile Paramount Pictures honcho Barry Diller declared awards season “an antiquity”, along with the movie industry that kept them propped up for more than a century. The business model, Diller says, of a movie “going to a theater, building up some word of mouth if it was successful, having that word of mouth carry itself over” has been overpowered by streams, clouds, and movie theaters closing in America and abroad as a reverberating byproduct of the COVID-19 lockdown. The very definition of a “movie,” he adds, “is in such transition that it doesn’t mean anything anymore.”

He’s right, of course. And yet, here we are again, rewiring this tired old circuitry to get audiences in the mood for another night of triumph, tears, suspense, and whatever else Oscar hype used to promise. What’s kind of ironic, if not all that significant, is that this year, there may be real suspense in a few of the major categories given the mixed results along the way in the awards leading up to March 12. As of this writing, all the trade publications and prognosticators are certain Everything Everywhere All at Once will win everything, everywhere, etc. As you’ll note below, I’m not as convinced, at least not for Best Picture.

I’m also not convinced that this will be the last Academy Awards broadcast, nor, for that matter, the next one, or the one after that. Because, as wobbly as things are with the Oscars, and as more people, even movie lovers, wish they would go away already, no one seems to have any ideas as to what, if anything, would fill the void they would leave behind. As with newspapers, all-star games, and other institutions struggling for new identities in the still-new century, the very nature of what a “movie” is and what the criteria is for assessing its value, artistically or commercially is, unavoidably, under review in several quarters. Whatever the case, the movie business as we once knew it may be dying, but movies are not; any more than opera, live theater, even the damn novel, all of which persist, despite no longer occupying the center of the zeitgeist.

In fact, what is a zeitgeist these days anyhow? If the Oscars are little more than a lame excuse to avoid dealing with that question, then, they’re good for something after all.

As always, projected winners are listed in bold with FWIW (For Whatever Its Worth) notes added whenever I feel like it.

Best Picture

All Quiet on the Western Front

Avatar: The Way of Water

The Banshees of Inesherin

Elvis

Everything Everywhere All at Once

The Fabelmans

Tár

Top Gun: Maverick

Triangle of Sadness

Women Talking

Let’s get this party started by clambering out on a limb. As I’m writing this, the Screen Actors Guild, the Producers Guild of America, and the Directors Guild of America have all given their top honors to Everything Everywhere All at Once with BAFTA dissenting by making All Quiet on the Western Front its choice for Best Picture. That digression, though hardly major, should be a hint that this season’s predictions shouldn’t be, if not set in stone, certainly written in ink. As the New York Times’s Kyle Buchannan tweeted, not since Apollo 13 swept the PGA, DGA, and SAG’s top prizes 28 years ago has a movie winning those awards fell short of winning the Best Picture Oscar. On the one hand, that’s a formidable precedent; on the other, if it happened at least once before…

At the risk of repeating myself (at least to those of you who’ve been paying attention to my annual dithering on these things), the Oscars, even in their present emaciated state, are trade awards, first, foremost, and for however long they go on. In the medium’s customary tug-of-war between Art and Commerce, the latter tends to have the upper hand in the Academy’s consideration. Neither the media nor the moviegoing public are factors in the voting except for those parts of the latter group with craft union cards within the moviemaking industry. Thus, most of the Academy’s final decisions have less to do with the quality of a motion picture and more to do with assessing its overall impact on their industry’s future. Hence, I put it to you: which of these eight movies has done more to bolster whatever’s left of the movie business’s sagging confidence?

Before you answer, I need to remind you that at this year’s annual Oscars luncheon, TG:M’s co-producer and star Tom Cruise made the biggest splash among its record-breaking 182 attendees; he was the Big Man On Campus, its Belle of the Ball, with none of the baggage he’s had to lug over the past 20 years. In a year with as many wide-open categories as this, the top prize may be the widest and most open of the competitions, excepting the feature documentaries. Draw your own conclusions, but at this moment, I can easily see Captain Maverick and his squadron booming and zooming to the winner’s circle. And because the movie was better than anybody had the right to expect, it wouldn’t be the most embarrassing Best Picture award in Oscar history. Too many others compete for that dubious honor.

FWIW: I doubt Prey or Nope, two of my own favorite movies from last year, would have made this list; nor would the tightly wound and ferociously topical Emily the Criminal and the sumptuously Hitchcockian detective story from Korea Decision to Leave. What all these had in common, as far as I was concerned, was a sense of each movie going about its business, doing what needed to be done in their allotted time, and keeping their audiences alert for surprise and possibility within tight corners. In short, they were the kind of movies I sought out in theaters or drive-ins in an earlier, different life.

Best Director

Martin McDonagh, The Banshees of Inesherin

Daniel Kwan, Daniel Scheinert, Everything Everywhere All at Once

Steven Spielberg, The Fabelmans

Todd Field, Tár

Ruben Öslund, Triangle of Sadness

Fablemans is a Steven Spielberg movie about Steven Spielberg. Some people have a problem with this, and I don’t know why. It’s not getting skunked the same way that his remake of West Side Story did a couple years ago. But you’d think a love letter to movies and moviemaking would be a slam dunk with voters. Instead, Team Daniel has been riding in triumph throughout awards season and there’s not so much as a pebble to trip them up to the winner’s circle.

Best Actor

Austin Butler, Elvis

Colin Farrell, The Banshees of Inisherin

Brendan Fraser, The Whale

Paul Mescal, Aftersun

Bill Nighy, Living

At the start, this category appeared to belong to Farrell or Fraser, whose SAG win may have put him back in play. But maybe it’s kind of a retroactive referendum on what people admired more about Robert De Niro’s Oscar-winning portrayal of Jake La Motta in 1980’s Raging Bull. Was it the all-out depiction in La Motta’s volatile personality or was it the fact that De Niro invested so deeply into the role that he made himself gain weight? Guess we’ll see.

Best Actress

Cate Blanchett, Tár

Ana de Armas, Blonde

Andrea Riseborough, To Leslie

Michelle Williams, The Fabelmans

Michelle Yeoh, Everything Everywhere All at Once

Everybody I know, including me, is rooting for Yeoh, though Blanchett’s been mounting a doughty and, it would appear, successful campaign to dispel the negative vibes her movie stirred up in the classical music community. Cate’s BAFTA win teases us into thinking this will be a photo finish, but somehow, I doubt it’ll be that close

FWIW: Every year, the Oscars always seem to single out a “little” movie with a broken, put-upon protagonist struggling with some malady that s/he cannot control until they find redemption at the end. This year, that movie is To Leslie and its principal beneficiary is Andrea Riseborough, whose controversial nomination came through an eleventh-hour campaign with big names (Kate Winslet, Amy Adams, and Gwyneth Paltrow among them) pushing her over. This in turn led to cries of foul, especially among the #OscarSoWhite veterans believing Risborough’s candidacy came at the expense of such Oscar-worthy lead performances as those of Danielle Deadwyler (Till) and Viola Davis (The Woman King), both of whom were nominated for SAG Awards, but lost to Yeoh. Till’s director Chinonye Chukwu accused Hollywood of “unabashed misogyny towards Black women.” She’s not altogether wrong. But it doesn’t mean Riseborough’s nomination is a manifestation of this prejudice. It’s legit. You come away from To Leslie with Riseborough’s all-out investment in her serial-fuck-up character resonating in your head. Do I think she’s better than Blanchett or Yeoh? Apples and oranges. Do I think Deadwyler was better in her movie than Riseborough was in hers? I’d say it’s a draw. Do I think Davis was better in Woman King? You bet I do because, as I’ve stated before on this platform, Viola Davis is God! Then again, I also would have wanted Aubrey Plaza represented here for Emily the Criminal. But who cares what I want? Not Hollywood. That, as we were once fond of saying, is show biz and biz-ness of any kind rarely plays fair. So, I say kudos to the coalition behind Riseborough for making their push. Someday soon, Black and Brown people will make their own Riseborough uprising because of the precedent it set. To repeat: that’s show biz.

Best Supporting Actor

Brendan Gleeson, The Banshees of Inisherin

Brian Tyree Henry, Causeway

Judd Hirsch, The Fabelmans

Barry Keoghan, The Banshees of Inisherin

Ke Huy Quan, Everything Everywhere All at Once

By now, a foregone conclusion. And, as with last year’s winner in this category, it’s also a great story: the little boy émigré from Vietnam who played Short Round in 1984’s Indiana Jones and the Temple of Down hitting the jackpot forty years later. Fun fact: Jeff Cohen, who played Chunk to his Data in 1985’s The Goonies, is now his lawyer.

FWIW: Keoghan was a surprise BAFTA winner in this category, and it may be because his poignant presence shined through the outsized personalities of Banshees’ two stars. He’ll get some attention, but, in many ways, he’s already won. As for Paper Boi (Henry), his day’s coming. Count on it.

Best Supporting Actress

Angela Bassett, Black Panther: Wakanda Forever

Hong Chau, The Whale

Kerry Condon, The Banshees of Ineisherin

Jamie Lee Curtis, Everything Everywhere All at Once

Stephanie Hsu, Everything Everywhere All at Once

Curtis’s SAG award shouldn’t have come as a surprise. For starters, she’s totally unrecognizable in the movie, at least at first. And Oscar loves it when the glamorous go all out to distort themselves on camera, especially when, in Curtis’s case, they’re Hollywood royalty. I’m now feeling it’s hers to lose. Bassett’s infusion of power and vulnerability helps ground what could have been an unwieldy popcorn blockbuster and made her an early favorite. But the MCU can’t withstand the accumulated might of ancestral movie legacy. Not this time, anyway.

Best Adapted Screenplay

All Quiet on the Western Front

Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery

Living

Top Gun: Maverick

Women Talking

On the one hand, giving an Oscar to a Nobel Prize winner like Kazuo Ishiguro (Living) would show elevated thinking on Hollywood’s part. On the other, Sarah Polley has quietly, diligently proven herself to be one of the world’s best writer-directors and I can’t see her walking away empty-handed from another one of these ceremonies.

Best Original Screenplay

The Banshees of Inisherin

Everything, Everywhere All at Once

The Fabelmans

Tár

Triangle of Sadness

Anything with Martin McDonagh’s name on it is all but automatically placed in this category’s pole position. This one’s an odd chamber piece, an astringent, overextended Laurel and Hardy sketch in which you actually feel the bumps on the noggin and see all the bruises, physical and otherwise. However thin the gruel, I can easily see it winning, though there’s always a chance that the momentum of EEAAO (“…with a moo-moo here and a moo-moo there…”) could sweep this one up.

Best International Feature

All Quiet on the Western Front

Argentina 1985

Close

EO

The Quiet Girl

Given a Best Picture BAFTA and eight other nominations, Edward Berger’s graphic, devastating take on Erich Maria Remarque’s novel is the surest bet on the table.

Best Animated Feature

Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio

Marcel the Shell with Shoes On

Puss in Boots: The Last Wish

The Sea Beast

Turning Red

I feel relatively alone in asserting that this spikier, darker take on The Puppet Who Wanted to Be a Real Boy may have been a more imaginative and adventurous movie than any of the Best Picture nominees if only in the way it risked pissing people off who cling to their memories of the Disney version, which, for the record, I love, too. Most of the experts think it’s a lock, but I’m sensing a groundswell of support for M. Shell.

Best Cinematography

All Quiet on the Western Front

Bardo: False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths

Elvis

Empire of Light

Tár

Another close race, this one primarily between James Friend’s work on All Quiet on the Western Front and Mandy Walker’s on Elvis. If Walker wins, she will be the first woman to do so. But Friend’s movie also is nominated for visual effects and production design, which experts say gives him the edge. Screw it. I’m going to put my chips on progress.

Best Documentary Feature

All That Breathes

Fire of Love

All the Beauty and the Bloodshed

A House Made of Splinters

Navalny

By far, the widest-open race this year. If precedent alone was a factor, Sara Dosa’s DGA prizewinner, Fire of Love, with its dual themes of nature and everlasting love (married scientists who perish in a volcanic explosion), would have the edge. Then again, voters’ hearts would be just as vulnerable to House Made of Splinters which is set in a home for neglected children awaiting adoption. But the timeliest of these nominees is Daniel Roher’s tense profile of the Russian opposition leader who survived poisoning by Vladimir Putin’s goons, recovered in Germany, and returned home to a hero’s welcome – and imprisonment. The winner may, as in previous cases, depend on whether voters want to assault the turmoil of what’s been happening in Russia and the Ukraine, or run from it towards more hopeful, or at least more heartening stories. I’ll guess I’ll just what-the-hell my chips on Roher’s film.

Best Score

All Quiet on the Western Front

Babylon

The Banshees of Inisherin

Everything Everywhere All at Once

The Fabelmans

Once more, with feeling, to 91-year-old John Williams, though Carter Burwell still hasn’t won one of these yet. Here as elsewhere, I’m not convinced Banshees is strong enough to pull him over the hump.

Best Original Song

“Applause” from Tell It Like a Woman

“Hold My Hand” from Top Gun: Maverick

“Lift Me Up” from Black Panther: Wakanda Forever

“Naatu Naatu” from RRR

“This is a Life” from Everything Everywhere All at Once

With Rhianna (“Lift Me Up”), Lady Gaga (“Hold My Hand”), and one third of David Byrne (“This is a Life”) in play, how is it possible that the showstopper in this bunch belongs to a Tollywood epic that somehow stormed the global marketplace? Everybody seems to have already taken its win for granted, but everybody, including me, has been wrong many times before on this category.

March 9th, 2022 — movie reviews

I’ve never believed there was a useful distinction to be made between “popcorn movies” and whatever’s meant by “prestige films.” Good movies are good movies and whatever’s left to talk about is marketing, nothing more.

And so, for that matter, is all this year’s pre-Oscar chatter about the decline in TV ratings for the awards ceremonies and the relative apathy among the public for movies considered “Oscar bait.” Do pundits and other assorted “observers” really think nominating Spider-Man: No Way Home for Best Picture is going to revive the Academy Awards’ profile among the masses? I don’t think so – and I happen to believe movies like Spider-Man should be nominated – as long as they’re good; just as I was pulling for Deadpool’s nomination (and for that matter, Leslie Uggams’) a few years back and wouldn’t have at all minded if Black Panther had won Best Picture over Green Book three years ago. It was, after all, the better movie in addition to being the bigger success.

Neither factor has ever really mattered when it comes to the Academy Awards. As I keep putting my blood pressure at risk to tell people who refuse to believe otherwise, the Oscars are trade awards voted and decided upon solely by those who work in the film industry. That means whatever gets nominated and rewarded depends on whatever mood prevails each year among a crowd of Hollywood working stiffs. And these mood swings are somehow immortalized (for at least three months or so) as the Best Movies of their particular year by cable news channels, slick magazines, and whatever’s left of the newspaper industry.

The social and economic upheavals of the last three years, especially the pandemic’s ongoing reverberations, are causing even legacy media institutions to wonder if this venerable charade is, at last, over and out. The celebration of the 50th anniversary of The Godfather’s release is a melancholy reminder of theatrical cinema’s once prominent place in American life and of how the old apparatus of making and hyping movies at all levels of society hasn’t existed since at least the second Clinton administration. Once again, I find myself asking, if we’re no longer sure what a movie is, then what the hell is an Oscar? And more to the point, what’s any of it worth?

I still don’t have an answer and I bet none of you do either. It’s one of those many 21st-century dilemmas for which an answer will surface on its own rather than materialize as a lightbulb over the head of an Instagram follower. For now, The Show in whatever form and however it’s packaged will go on as will the usual griping and grousing from those who don’t care and never have about Academy Awards. I’m no longer sure I care much either. But I’m here. Again. And many of you are or will be. I can hear you growling and snapping.

Once again, projected winners are in bold and, whenever applicable or appropriate, an FWIW (For Whatever It’s Worth) note will be added to each category.

Best Picture

Belfast

CODA

Don’t Look Back

Drive My Car

Dune

King Richard

Licorice Pizza

Nightmare Alley

The Power of the Dog

West Side Story

Even before cowpoke’s cowpoke Sam Elliot blurted his indelicate critique against Power of the Dog (and these days, Oscar Season just isn’t Oscar Season without some occasion for public outrage and virtue-signaling to keep the yahoos distracted), Jane Campion’s western was showing a slight drop from the front-runner status it seemed to nail down upon its premiere last fall. The first wave of acclaim, along with the initial flurry of critics’ awards and field-leading 12 Oscar nominations, was followed by an unusually quick and acerbic blowback. I’d expected Belfast to be the principal beneficiary of this shift in Power/Dog’s fortunes – and it still might be. But lately it’s CODA that’s been gathering a head of steam since it won a best-movie-ensemble award from the Screen Awards Guild (SAG).

Not that SAG’s record as a Best Picture harbinger can be counted on to float without sinking. Less than half of the last 26 winners of that award carried their luck over to Oscar’s big prize. And besides (trying not to spoil things here), CODA’s story of a working-class teenager choosing between fulfilling her destiny as a singer and helping her financially strapped deaf family fits snugly into how SAG’s members see their own careers and aspirations. You wonder if that story arc is likely to patch into other Oscar voting blocs. Heck, yeah, it is, especially if it makes everybody cry as they’re watching. At the time I’m writing this, it’s still Power of the Dog’s race to lose, and as one of my correspondents suggests, Sam Elliot’s “POS” tirade could end up gaining added sympathy for Campion and her movie. But recent history has me regretting every time I’ve underestimated the power of “feel good” movies.

FWIW: Here’s where I usually talk about what I liked best last year, Oscar-nominated or not. Mostly I am, and plan to remain, confounded and aggrieved over Passing, its two stars Tessa Thompson and Ruth Negga, and its first-time director Rebecca Hall getting skunked out of any nominations whatsoever. In the long run, it may be all for the best; movies that are bold and enigmatic in their own time often find greater acceptance in another time – and I still believe in time.

Speaking of boldness, I keep insisting that Nightmare Alley wasn’t a “remake” of a 1947 noir classic so much as a total reimagining as though 1945’s Detour (a far bleaker and grittier exemplar of “noir” movie than the original Nightmare) had a head-on collision with a Stephen King movie adaptation from the mid-to-late-1980s. It got a few Oscar bids in technical categories, but you’ll never see it win anything on live TV because of how they’re planning to telecast this year’s ceremonies.

The Steven Spielberg-Tony Kushner revival of West Side Story deserved much better upon its theatrical release than it got from the public and from industry wise guys too quick or, maybe, too eager to stamp it as a disaster. These days, I’d say, the word “disaster” weighs too much to casually fling at a movie whose biggest mistake was having the bad luck to pile into movie houses during a pandemic. To me, there’s no greater portent for the inevitable fall of the multiplex than the turnaround in overall reaction to West Side Story 2.0 in the weeks since it dove into the streams, as it were.

I also have a qualified recommendation for The French Dispatch that reflects the latent generosity, or greater tolerance from my older, more indulgent self towards Wes Anderson’s intricate jewelry boxes. Or maybe it’s that I’ve lately found his knee-jerk critics more insufferable as time passes for their all-too predictable carping and jeering.

Best Director

Kenneth Branagh, Belfast

Ryûsuke Hamaguchi, Drive My Car

Paul Thomas Anderson, Licorice Pizza

Jane Campion, The Power of the Dog

Steven Spielberg, West Side Story

Even if Power/Dog doesn’t get the Big One, it won’t keep its director from Getting Hers, as it were. It used to be an anomaly for Best Film and Best Director winners to diverge. It’s now happened often enough in recent years to be taken for granted. Campion still has lots of support for this one whatever Sam Elliot says. And, as I said earlier, he may even have unintentionally helped her stay in front of this pack.

FWIW: If I had a vote on this one, Spielberg would get it; if nothing else, just for withstanding all the catcalls he was getting, even as he was still trying to finish it against stiff odds. (e.g., “Why are you bothering? The first one was just fine!” Or: “Why are you bothering? This old warhorse is too creaky, an anachronism, etc.”) Branagh could also pick Campion’s pocket, but only if Belfast wins Best Picture.

Best Actor

Javier Bardem, Being the Ricardos

Benedict Cumberbatch, The Power of the Dog

Andrew Garfield, tick..tick…Boom!

Will Smith, King Richard

Denzel Washington, The Tragedy of Macbeth

As good as I am at intuiting such things, I still can’t tell for sure how much Hollywood still loves Will Smith, despite the hugs, kisses, and backslaps he got for winning the SAG prize a few weeks back for this same role. And yet I can’t imagine anybody else from this list taking the Oscar from him except possibly …Denzel, whom I’m sure Hollywood loves for still being able to open a movie on name recognition alone while always delivering nothing less than an A-level performance. His Macbeth isn’t his very best, but it’s good enough. Smith’s rendering of the Williams sisters’ volatile, complicated daddy, on the other hand, IS his very best. Not a slam dunk, maybe; Cumberbatch also lurks in the weeds. But taking everything into account, it’s close to a no-brainer.

Best Actress

Jessica Chastain, The Eyes of Tammy Faye

Olivia Coleman, The Lost Daughter

Penelope Cruz, Parallel Mothers

Nicole Kidman, Being the Ricardos

Kristen Stewart, Spencer

Chastain’s SAG award vaulted her to the foreground of a not-terribly-strong-but-highly-competitive field. It’s a big, bravura performance, exactly the type that actors love to reward. And however effective, say, Kidman and Stewart (especially) were at embedding themselves in their real-life personas, it’s now Chastain’s to lose.

Best Supporting Actor

Ciarán Hinds, Belfast

Troy Kotsur, CODA

Jesse Plemons, The Power of the Dog

J.K. Simmons, Being the Ricardos

Kodi Smit-McPhee, The Power of the Dog

Another case where the SAG vote seems to have locked this one up. McPhee had the early lead, but with Plemons’ nomination for the same move came that hoary old saw about “splitting the vote,” which I never thought mattered much and won’t this time either. The veteran Hinds enjoys much affection and esteem among his peers and his turn as the grandfather in Belfast is lovely and touching. But Kotsur’s movie now has greater momentum and his is the far more compelling backstory.

FWIW: There was a moment early on when I thought Simmons had a fair shot of getting his second one of these and it had mostly to do with how even those who disliked Being the Ricardos were always happy to see his William Frawley appear on-screen.

Best Supporting Actress

Jessie Buckley, The Lost Daughter

Ariana DuBose, West Side Story

Judi Dench, Belfast

Kirsten Dunst, The Power of the Dog

Aunjanue Ellis, King Richard

Rita Moreno made me tear up when she soloed on “Somewhere” in West Side Story. I was sure that alone would have made inevitable another nomination, even another win 60 years after she copped this same award for playing Anita. Still, DuBose is getting unadulterated props – and prizes — for her fiery, effervescent, and deeply touching turn in the same role. She should have little-to-no trouble adding another trophy to the pile…

FWIW: …but if it were up to me, I’d ship this puppy posthaste to Aunjanue Ellis for all but stealing her movie out from under the Fresh Prince’s fabled jawline. Her character’s confrontation with a meddling neighbor was an aria of last-nerve enervation with Other People’s Bullshit. Love her, even if hardly any other forecaster seems to notice, or care.

Best Original Screenplay

Belfast

Don’t Look Up

King Richard

Licorice Pizza

The Worst Person in the World

Paul Thomas Anderson may be the most original and audacious living American filmmaker – which won’t necessarily help him win this one. You need to be in the mood for Licorice Pizza’s first-this-happens-then-this-happens-and-then-this-happens storytelling, which would be far more welcome to moviegoers in the 1970s when this story takes place. I was down with it because that decade was my most formative as a cineaste and it is probable there’s a majority of voters in this category who are likewise disposed. But I sense this one’s heading to Northern Ireland.

Best Adapted Screenplay

CODA

Drive My Car

Dune

The Lost Daughter

The Power of the Dog

This one’s wider open than it seems with all except, maybe, Dune carrying strong, if not overpowering cases on their behalf, and none as innovative as Kushner’s delicate, detailed upgrade of West Side Story‘s book, which was totally ignored. Even with CODA‘s late surge to the finish line, I’m thinking Power/Dog may have the edge. But not by a lot.

Best International Feature

Drive My Car

Flee

The Hand of God

Lunana: A Yak in the Classroom

The Worst Person in the World

Drive My Car’s triumphant ride through last year’s festival circuit made this elegiac dissection of grief an early favorite in this category. But this is an especially strong field, with both the groundbreaking Flee and Worst Person in the World drawing homestretch buzz. The Ukraine invasion could be a rogue factor favoring Flee if not in this category, then in one of the other two where it’s contending. Even past winner Sorrentino’s Hand of God has a puncher’s chance. Keeping my finger here for now but prepared to move it at any time.

Best Documentary Feature

Ascension

Attica

Flee

Summer of Soul

Writing With Fire

I’ve had dismal luck forecasting this category in recent years and I’m not quite sure about this pick either. As in past years, the outcome of this contest depends on whether Hollywood votes its hopes or its fears. Both impulses are very much in play in the present tenseness. As much as I was transported as everybody else by Summer of Soul’s found objects, I’m going to presume that both innovation and urgency count for a lot with this crowd and believe this is where Flee collects its Oscar.

FWIW: Once again, the grizzled ex-newspaperman in me is rooting for the nominee that shines a light on journalism overcoming formidable odds in foreign lands. Last year it was Romania’s Collective; this year it’s India’s Writing With Fire. Next year, it’ll be some doughty, put-upon independent weekly near the Urals – or, more likely, Central Florida.

Best Animated Feature

Encanto

Flee

Luca

The Mitchells vs. The Machines

Raya and the Last Dragon

Sony Animation’s rowdy, whip-smart sugar rush of a techno-satire is, in every sense, the wild card of this bunch. That it’s already won 25 awards from critics’ associations and other groups may come as a surprise to those who’ve watched only its first ten minutes or so on Netflix (where, BTW, you can still find it, even if it’s not always highlighted on the home page). It seems at the outset like such a typical example of formulaic dysfunctional-family slapstick that you’re almost shocked by how meta it gets without losing its edge, its warmth, or its run-amuck tempo. It’s by no means a sure thing, especially with not one, but two Disney entries and the aforementioned Flee as competition. But brains-and-heart, along with the much-beloved Olivia Coleman providing the voice of a megalomaniacal smart phone, seem to me a formidable combination of factors for victory.

FWIW: Unless I’m wrong and either Encanto or Luca end up in the winner’s circle after all.

Best Cinematography

Dune (Grieg Fraser)

Nightmare Alley (Dan Lautsen)

The Power of the Dog (Ari Wegner)

The Tragedy of Macbeth (Bruno Delbonnel)

West Side Story (Janusz Kaminski)

Once again, a good, strong field, all of them deserving. Because of that, I choose to go with my personal preference. Fraser may win it anyway. But this movie’s images keep crawling back into my head the way Dune’s do not.

Best Original Score

Don’t Look Up (Nicholas Ball)

Dune (Hans Zimmer)

Encanto (Germaine Franco)

Parallel Mothers (Alberto Iglesias)

The Power of the Dog (Jonny Greenwood)

Greenwood deserved this award in 2017 for Phantom Thread and he’d probably get his first win this year for his appropriately itchy and eccentric arrangements for Power/Dog if Zimmer, who’s only got one Oscar (The Lion King, 1994) to show for his 12 nominations, hadn’t done some of his finest work ever in laying down tracks, as it were, on Planet Arrakis.

FWIW: I’m going to assume, however, that the Encanto soundtrack’s prolonged stretch run on the pop charts isn’t lost on voters, many of whom likely have kids in the house who’ve played it to death on whatever platform or machine they have. Not that such factors have always tipped the scales; voters in this category like to think they’re above such matters. But nobody should be surprised if Encanto’s name is called. On any of these.

Best Song

“Be Alive” from King Richard

“Dos Oruguitas” from Encanto

“Down to Joy” from Belfast

“No Time to Die” from No Time to Die

“Somehow You Do” from Four Good Days

Does Billie Eilish beat Beyoncé? Do either of them expect to beat Disney? Or Van Morrison? (Well, yeah, because we’re all supposed to be ticked off at Van Morrison, right?) And what about Reba McEntire? Nobody knows from her movie anyhow. Maybe that’s why she’ll win. But I’m going with who’s hot right now and that would be…would be….could be…um…

December 20th, 2013 — movie reviews

Can anybody make a serious, imaginative movie about slavery without being either ignored or picked at? Quentin Tarantino spent almost as much time shaking off flak for his flamboyant genre goof Django Unchained as he did taking bows and counting money. When Jonathan Demme made Toni Morrison’s Beloved into a far-better-in-hindsight movie in 1998, not even the Great and Powerful Oprah’s approbation of, and involvement in its production could make black people assemble en masse to see it when it was released. (Or anybody else. The cost was about $58 million; the movie made about $23 million, at best.)

At least, nobody’s ignoring 12 Years a Slave. It’s at or near the top of just about everybody’s year-end list of best movies. As of the second week of December, it’s made more than $35 million in American ticket sales with more expected around the bend in advance of Oscar season. Still, the movie has attracted its own high-visibility flak from such critics as Armond White, who believes Steve McQueen’s often-graphically violent rendering of Solomon Northrup’s testament as “torture porn” and “less a drama than an inhumane analysis.” David Edelstein, though he believed the movie “smashingly effective as melodrama,” is less fond of McQueen’s “cold, stark, deterministic” approach to the material.

For the record, I admired 12 Years a Slave far more than I loved it. An American/Hollywood director, no matter how smart or savvy, wouldn’t have trusted as much visually as McQueen does here. (In case you didn’t know, he’s black and British.) He isn’t afraid of stillness, of the tension and energy that reside in the act of waiting, as in the first frame, which in just showing the barely contained anxiety in the faces of slaves, gets the movie moving. That said, I doubt very much I will want to see it again. Do I need to watch, once again, a thin young woman getting whiskey tumblers thrown at her head and then having her back stripped of her ebony skin the way you strip a tree of its bark? I do not – and part of me wonders who would, or who needs to.

Still, because the movie is directed by a black man and is written by another (novelist John Ridley), 12 Years a Slave doesn’t get the same mauling Steven Spielberg’s Amistad (1997) received in some precincts for making ciphers of its mutinous African slaves and using their rebellion as a vehicle for white nobility. And I doubt very much the contrarian attacks on McQueen and his film will keep it from winning more awards; any more than Django’s critics kept Tarantino from collecting a screenwriting Oscar.

But no amount of gold statuettes will stop the haters from jumping on the next filmmaker who wants to take yet another hard, idiosyncratic shot at America’s Original Sin. The only solution: Take more shots, make more movies, go as odd, off-base, strange, funny, stern, cold, hot or heavy as the market can bear – and then, if you’ve got the gall, go further than that. There’s no dearth of material to draw upon, from the still largely undiscovered country of slave narratives to contemporary fiction by African American writers who are claiming autonomy over their ancestral experience through daringly imaginative means.

You like lists. Here are places to go for such material:

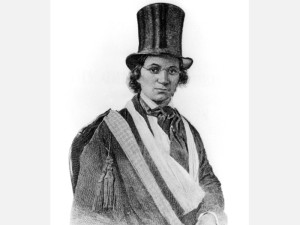

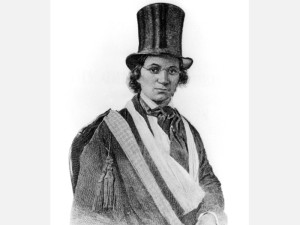

William and Ellen Craft – True story: They were married in bondage in 1846 and escaped two years later from Georgia to Philadelphia in disguise; she (above) as an invalid white man and he as “his” valet. It would take someone with an equally attuned ear for both injustice and comedy, but it could be done.

The Good Lord Bird – Being this year’s surprise National Book Award winner, James McBride’s picaresque comic saga of a young slave boy mistaken as a girl by abolitionist John Brown has likely attracted a few cautious glances from Hollywood. Sophisticated historical satires aren’t exactly meat-and-potatoes fare for multiplexes, no matter who’s involved. But it would be funny, again, if the right tone is struck.

Flight to Canada — An Ishmael Reed seriocomic pastiche that’s never received the credit it deserves for initiating a wave of black novelists claiming imaginative autonomy over their ancestral past in daring, often incendiary fashion. I can’t begin to imagine who would make a movie out of it or what kind of movie it would be. But whenever or however it’s done, it’ll be different from anything that came before.

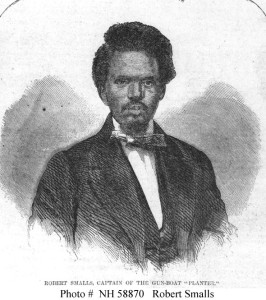

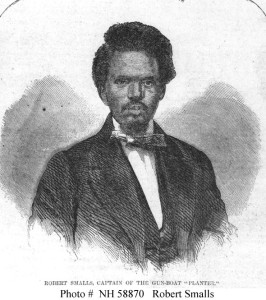

Robert Smalls Steals a Rebel Ship– Another true story; this one about a slave (above) who in 1862 commandeered a cotton freighter with a crew of 17 fellow escapees and managed to hide his identity from Confederate checkpoints, even Fort Sumter, towards the open sea until he was able to raise a white flag to Union blockaders. That alone would be a good movie, though it was just the beginning for Smalls, who later became one of the few African Americans to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives during Reconstruction. (Speaking of which, don’t you think that by now, some great movie about black folk during Reconstruction could be made to counter that damned Birth of a Nation? Just add it to the wish list.)

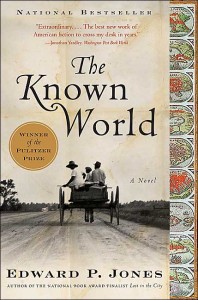

The Known World – Edward P. Jones’ award-winning novel about blacks owning black slaves already made readers’ heads spin off their necks. A movie version could magnify the shock-and-awe and I’m being REALLY optimistic when I say it could be done. But I’m betting it wouldn’t cause nearly as much trouble as…

The Confessions of Nat Turner – And, yes, I mean William Styron’s version, which has been cherished and despised in near-equal measure by black and white readers alike. America wasn’t ready for Turner in the 1830s and they still aren’t ready for him in whatever form he’s presented or imagined. Which doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be attempted.

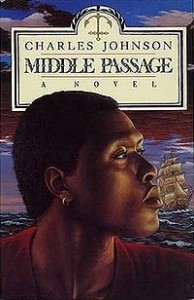

Middle Passage and Oxherding Tale — A pair of thinking-person’s ripsnorters by Charles Johnson; the former, as with 12 Years a Slave, puts a freed slave in harm’s way as he finds himself aboard a raucous slave ship heading back to Africa to pick up more “chattel.” The latter chronicles the adventures of a half-white-half-black slave negotiating his way through both worlds with philosophic insight and canny resourcefulness.

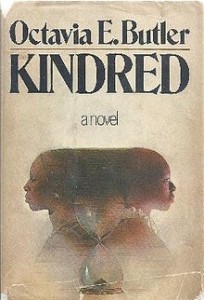

Kindred — Let me quote from an Amazon review of the late Octavia Butler’s breakthrough SF novel: “Dana, a black woman living in Los Angeles in 1976, is inexplicably transported to 1815 to save the life of a small, red-haired boy on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. It turns out this small boy, Rufus, is one of her white slave owning ancestors, who she knows very little about. Dana continues to be called into the past to save Rufus, and frequently stays long periods of time in the slave owning South. The only way she can get back to 1976 is to be in a life threatening situation.” How is this NOT a movie waiting to happen? Why hasn’t it happened by now?

And on and on and…

November 14th, 2012 — movie reviews

Lincoln – (IMMEDIATE REACTION: And what if last week’s election had gone the other way? Would that 13th Amendment have been repealed? Oops. Spoiler…Sorry about that, those-of-you-who-slept-through-high-school-history….)

Race prowls, growls and snaps along the edges of Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln as it never could throughout the recent political campaign. And to briefly digress, the evasions have only gotten worse since last Tuesday. So far, no one in what Sarah Palin and I love to label the “lame-stream media” wishes to acknowledge the specter of racism in these calls for secession by spoilsports in Texas and elsewhere. I’d like to believe, as Lincoln widens its presence in the Great American Multiplex, that the neo-Victorian lummoxes now wasting their energies on the Petraeus-Broadhurst Misadventures will be compelled by the movie to see this neo-Confederate furor as the maypole-dance-for-bigotry that it is. But as a good friend of mine sadly reflected today, it would have been nice to think that last week’s election results meant we’d finally put away all our childish things.

As vital as I think Lincoln is to generating a more perfect discourse on race and union, I think the movie’s gradual release better facilitates such maturity. A more big-footed nationwide bust-out of any Spielberg movie conditions audiences to expect pyrotechnics and razzle-dazzle, if not dinosaurs and aliens. This is a deliberately-paced, serious-but-not-altogether-solemn epic that needs all of its 150 minutes to convey the urgency, languor and ultimate viability of the democratic process. If Steven Spielberg’s showmanship can’t make compelling cinema from material as multi-layered as Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals, nothing can. It can, and does.

(And, for the record, boys and girls, there are plenty of dinosaurs and exotic beings in this one as well, if only metaphorical ones. You’ll see what I mean.)

As with Amazing Grace, Michael Apted’s handsome, relatively neglected 2006 movie about Britain’s abolition of slavery, Spielberg’s Lincoln isn’t about African American rights so much as it is about politics itself, and how time, personality, and the velvet-fisted power of persuasion can converge to bring about epochal, seemingly miraculous transformation. Abraham Lincoln’s efforts to pass the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery (little noted and not as long remembered as the Emancipation Proclamation) provides a surprisingly wide lens for viewing the contradictions and complexities of both the Republic and its haggard-but-dauntless leader in the final months of its greatest crisis. Among the many small miracles wrought by Tony Kushner’s script (and the movie is as much Kushner’s as it is Spielberg’s, maybe more) is its seamless compression of the personal travails of its protagonist with the brilliant calculation of his maneuvering. You’d have to know going into the theater that, however much the movie is packaged as civic education, you’re not going to visit a stone edifice. You’d also have to know that Daniel Day-Lewis, whose preparation is so diligent and fertile that it can sometimes spill onto the scene, nails down everything there can possibly be about Lincoln’s voice and physical movement, even the way he nestles against his sleeping youngest boy, to leave little or no doubt that this is how “our one true genius in politics” (vide Robert Lowell) really behaved in sorrow, anger and, most tellingly, in jest. (Would it really ruin things for you if I disclosed that Lincoln tells a dirty joke in the movie? Or would it make you more curious? Either way, I’m not sorry. At least I didn’t tell the joke.)

As good as Day-Lewis is, it’s not as dominant a performance as you might expect — or dread. Tommy Lee Jones, that proud son of the once-and-future Republic of Texas, dines robustly on scenery as the Pennsylvania abolitionist congressman Thaddeus Stevens, treated so shabbily by D.W. Griffith in Birth of a Nation and here given some of the better lines not assigned to Lincoln himself. Sally Field’s Mary Todd Lincoln, though nowhere near as edgy as Mary Tyler Moore’s version in the 1988 TV mini-series version of Gore Vidal’s Lincoln, is as persuasively grounded as she is borderline hysterical. Everyone else, from Bruce McGill and David Straithairn as cabinet stalwarts Edwin Stanton and William Seward, respectively, to a near-unrecognizable James Spader as ringleader of Lincoln’s back-ally lobbyists, makes vivid use of on-screen time, even Lee Pace as the flamboyant Copperwood Democrat Fernando Wood who wanted New York to secede and Justified’s peerless Walton Goggins, his wormy magnetism on that show checked here in the role of a tremulous fence-sitting Democrat fiercely tugged by both sides in the amendment debate.

And what about the African Americans? Well, as seems customary in the aforementioned lame-stream, they talk less here than they are talked-about. Gloria Reuben’s Elizabeth Keckley, dressmaker and “confidant” to the First Lady, is permitted here to ask Lincoln the question most black people are more likely to ask of him now: How, Mr. President, do you really feel about us? Mr. President finesses the answer in the movie with precisely the same ambiguity with which he dealt with the race question all his life. (He was never as ambiguous on slavery itself. The distinction isn’t as clear here as it perhaps should be, but it’s there.) David Oyewelo, as one of the black Union soldiers speaking directly with Lincoln at the movie’s beginning, is far less credulous, peering at the president’s amiable façade with visible skepticism over its owner’s commitment to that “new Birth of Freedom” cited at Gettysburg months before the movie’s story begins.

But if black people aren’t as conspicuous as whites in Lincoln, race, as noted earlier, rages insistently throughout, stalking the historical figures like a rough, fearsomely mythological beast whose presence drives everyone’s actions, even – especially – the hesitation or outright refusal to act at all. And the movie is not the least bit shy implying that it is hysteria towards the very idea of “race-mixing” rather than the dark race of the despised minority itself that is most complicit in the Civil War’s bloodshed. Nowhere is this made more visually striking than after the unsuccessful attempt by Confederacy vice-president Alexander Stephens (Jackie Earle Haley) and his “commissioners” to retain slavery as a prerequisite for a negotiated settlement between North and South. The impasse fades to the image of a city in flames illuminating the night, followed by a gloomy ride by Lincoln and assorted military officers through a sooty, corpse-riddled battleground in Virginia. At such a point, those familiar with Lincoln’s life and words might be inclined to think of his 1858 speech in Edwardsville, Illinois when he dares to ask whites about dehumanizing and subjugating blacks: “Are you quite sure the demon which you have roused will not turn and rend you?”

I bet Tony Kushner knew that speech. I’m also betting that Kushner, who’s on-record defending Barack Obama’s circumspection and cool resolve against the dismissive criticism from Kushner’s left-wing allies, worked on this screenplay over the past few years with the intuitive sense that the 44th president’s struggles to finesse necessary transformation against ferocious and, at times, irrational opposition mirror those of the 16th president. Such perception gives his script a breadth, passion and level of commitment rivaling those of his stage work, notably, inevitably, Angels in America.

Lincoln, as the film takes pains to point out, is not perfect – and neither is Lincoln. Its ending comes across as Spielberg’s surrender to the temptation of making things obvious to the audience. It needed to end a few minutes earlier. (No, not this time. See for yourself.) Still, though we’re all in dire need of remedial history and (God knows) civics, Lincoln arrives not as a $50 million classroom lecture, but as a deeply enthralling diorama of tragedy and triumph bridged by the worst (avarice, bigotry, meanness of spirit) and best (equanimity, perspective, the enduring power of the open mind) from our many selves. And in case I didn’t make it clear at the outset, I’m as surprised by all this as you are – or will be.