Entries from May 2013 ↓

May 30th, 2013 — jazz reviews

Dammit.

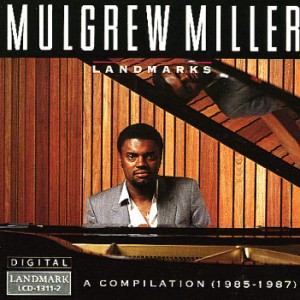

I had not only hoped, but also expected that Mulgrew Miller would have one of those lives and careers that endured for decades longer than he was allotted. He seemed destined to become one of those gray eminences of the jazz keyboard who would be around for another generation or two as a living exemplar of jazz piano’s essential verities very much in the manner of Hank Jones, Tommy Flanagan, John Hicks, Kenny Barron and Barry Harris. He’d found a niche at William Paterson University as director of jazz studies in which role he formally – and from the evidence here, effectively – carried out what he’d been doing informally since his 20s: influencing and mentoring younger musicians eager to follow his example.

As others have been pointing out since yesterday and will likely continue to do so over the next several days, Mulgrew Miller played with a faultless blend of grace, lyricism, clarity and unassuming resourcefulness that threaten to attract the label of “jazz pianist’s jazz pianist.” While this is intended as a compliment (and there are far worse things people can say about you), it also feels reductive, inexact and inefficient – especially when one gazes at the vast and expanding field of jazz pianists who have legitimate claim to that title. Each of us, in whatever trade or calling we pursue, is the sum of our accumulated influences and experiences; it’s what we do with that internal file that matters. When I listen to Miller play, I hear a generosity of spirit, inventive enough to keep your attention, yet deeply grounded in the rhythmic and harmonic foundations of what, for want of a better term, is considered “post-bop” jazz. You don’t always have to bend or twist tradition out of shape in order to get a rise out your listeners. You can endow the familiar with such authority, power and dynamism that it achieves a kind of eloquence that lingers in the imagination. As a leader and as a sideman, Miller hit those points so frequently that he created his own posse of devotees who followed him from an evening’s session at the late, lamented Bradley’s in the Village to whatever album was lucky enough to have him in the roster.

I’m lucky, in any event, to still have some of the now out-of-print discs he recorded in the early-to-mid-1990s for Orrin Keepnews’ Landmark label and on Steve Backer’s Novus series. (My favorite from the former: 1992’s Time and Again; from the latter, 1995’s With Our Own Eyes. They’re both worth hunting for in used-music bins, on- or off-line.) He also assembled quite a catalog as a leader on the MaxJazz label, especially the two-disc Live at Yoshi’s trio sessions. He always seemed so prolific and busy that you took it for granted that his protean work ethic would receive even greater rewards further down the road with the kind of wider recognition that reached Flanagan, Jones and others in their golden years. But he – and we – have been cheated out of that prospect. Dammit. Again.

May 24th, 2013 — movie reviews

IMMEDIATE REACTION: I had a good time. I expected to. I needed more.

By now, unless you’re sticking your fingers in your ears and going “La-la-la-la” whenever somebody brings the matter up, you’ve probably heard that Star Trek: Into Darkness is supposed to be a riff on 1982’s The Wrath of Khan. Either I’m on the wrong meds or more senile than I imagine, but wasn’t its predecessor supposed to be a rejiggered version of Khan? And if so, is this how it’s going to be from now on, all these new actors in old roles and “classic” uniforms replaying variations on the same story (e.g. evil madman seeks apocalyptic revenge for real and/or imagined crimes)?

If so, then I guess nobody wants to make Star Trek movies any more. Because, let’s face it: Into Darkness isn’t a Trek movie. It’s got all the characters from Trek and the actors who play them are all very good; in one, maybe two cases, even better than their predecessors. But it’s more a movie about Trek than it is a Trek movie. It roots around the attic, appropriating old tropes and familiar names to make the devotees nod in recognition. But what I liked most about J.J. Abrams’s 2009 reboot was its impudent intent to make everything new while remaining attentive to the basic enthusiasm for human possibility that made Gene Roddenberry’s franchise linger for so long in the collective unconscious. (From one dedicated, mildly crazed TV show-runner to another…) Abrams’s follow-up, by contrast, seems content to use Kirk, Spock, Scotty and the rest as action figures that serve the corporate model for summer thrillers; most especially, the Great American Multiplex’s persistant yearning for revenge fantasies along with the attendant surges of explosions, kick-boxing, mass carnage and the obligatory, egregious deaths of beloved father figures. (Be warned: I’m going to respect the “NO SPOILERS” mandate only so much. If you care that much about what happens in this movie, you’ve had plenty of time to see for yourselves.)

True, I wasn’t bored. Which surprises me since there was so little about In Darkness that was new, either in the plot points germane to the Trek mythos or in the usual heavy machinery assembled for standard-issue popcorn phantasmagoria. In fact, I bet the hard-core Trekkers (sic) had themselves a fine time pointing out all the scenes, set pieces and dialogue that had some connection with any and all of the varied Star Trek TV shows and movies. I bet if they tried really hard — and, trust me, so many of them don’t need to try – the SF-movie savants could point out references to other big-ticket movies in their favorite genre. Independence Day cornered the market on such shamelessness, only no one to this day considers it shameless. (It’s a classic, doncha know?) Whatever you call it, this sampling would be barely tolerable if it weren’t offset by the pleasure you get from watching the cast settle into their retrofitted characters. Chris Pine’s Kirk, though properly brash and impulsive, doesn’t yet have the William Shatner strut, though he seems to be quietly assembling his own brand of hauteur to carry into future episodes. Zachary Quinto’s Spock here shows more of the character’s original diffidence; of all the new actors, he’s the most thoroughly comfortable in his (tinted) skin. I still do not buy the office romance between Spock and Zoe Saldana’s Uhura for a nanosecond, but I am loving how she’s taking advantage of Trek 2.0’s greater breadth and depth of her character’s conception. I wish there were much more of John Cho’s rigorously circumspect Sulu, Anton Yelchin’s super callow Chekov and Karl Urban’s somewhat constrained Bones McCoy. I can’t yet tell whether Abrams and his team aren’t quite into the idea of McCoy, which would be a fatal mistake, or whether Urban doesn’t yet have a handle on him. The writers do seem very fond of the idea of Scotty rendered by Simon Pegg as a puckish grump with overcompensation issues. The revision plays to Pegg’s strengths and I’m guessing this series has bigger plans for him than they do for Urban – which would, again, be a big mistake since Trek’s classic verities are rooted in the tug-of-war between the hyper-passionate ship’s doctor and the coolly rational First Officer.

But I’m no longer sure Abrams really cares about the foundations of the old Star Trek as he does in critiquing, if not subverting Roddenberry’s vision. Let me put it another way: Why bother doing the Khan story, not once, but twice? Is it just to show how you can build a better Enterprise? As much as we love these characters in action no matter who’s playing them, it wasn’t just who they were or what they did, but what they represented to us back in 1966: Hope for the future. We’ve not only made it further out in space, but we seem to have managed to make ourselves better, smarter, more tolerant people. We figured out how to live together so well that we seem to be able to get along with people from other planets without being freaked out by the shape of their ears. Now what? That’s what we came for every week. What do we do with this wider perception of our own humanity as we head out yonder? Just as important, what DON’T we do? What is it about this expanded knowledge that keeps us from acting as stupid as some of the beings we encountered on this five-year mission, human or extraterrestrial?

These are the kinds of questions we counted on science fiction to engage, if not necessarily answer. And while we dug watching Kirk and the crew in all those cool martial-arts matches with Klingons and Romulans, the action sequences were access points for the question we knew Star Trek had to ask at some point every week: What does it mean to be human? Into Darkness is into the action sequences, but they seem placed there to sustain our thirst for retribution, which the movies seem to have been exploiting ever since (I’m going to say) 9/11. We no longer seem interested in seeking new life and new civilizations, but in kicking ass and taking names of those bullies who slaughter innocents and blow up our buildings. This yearning for the big win over terror may be who we are. But is it who we want to be? If Abrams and his co-writers are serious about this five-year mission the Enterprise is about to begin, maybe they’ll allow us to find out. But I don’t hold a lot of hope about this. Maybe that’s who I am.

May 3rd, 2013 — jazz reviews

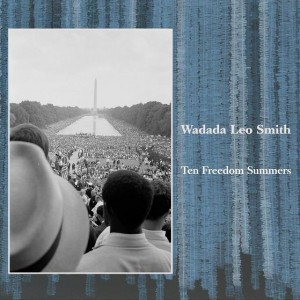

The best jazz recording of 2012, much like science or magic, doesn’t easily yield its secrets – which is the main reason it didn’t make my Top-10 list. I simply didn’t get to it all in time. Still, with or without me (and gratifyingly so), Wadada Leo Smith’s Ten Freedom Summers has by now received most of the formal acclamation it deserves: Finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in music, awards from the Jazz Journalists Association for Smith as musician and trumpeter of the year, a three-night live premiere last week at the Roulette in Brooklyn. I suspect that once the four-disc set on Cuneiform Records seeps into the shared consciousness of receptive listeners, it will continue to provoke, haunt and inspire. The greatest music – the greatest anything – doesn’t end when you stop absorbing it. Your reactions, primary and secondary, are part of the artistic process. They’re supposed to be, anyway.

Each of the nineteen compositions in Smith’s five-plus-hour opus announces itself as a chapter in American history from the 1857 Dred Scott case to the 9/11 terrorist attacks. But the thematic core of Ten Freedom Summers, as its title suggests, is the decade of national transformation that began with the 1954 Supreme Court decision declaring school segregation unconstitutional and the 1964 summer that saw both Congress’s passage of the most sweeping civil-rights legislation since Reconstruction and the Mississippi “Freedom Summer” Project during which activists risked (and lost) their lives trying to enfranchise the state’s besieged African-Americans. With Smith on trumpet leading both his Golden Quartet/Quintet of pianist Anthony Davis, bassist John Lindberg, percussionists Pheeroan ak-Laff and Susie Ibarra and the nine-member Southwest Chamber Music Ensemble conducted by Jeff von der Schmidt, the work spools forth as a meticulous inventory of mood more than a sweeping pageant of struggle. It doesn’t chronicle its noteworthy events so much as search for their deeper emotional currents and, in doing so, compels the listener to react to history beyond text and shadow – and even further beyond the blithely-dispensed shorthand of newsreels, archival photos and sound bites.

I wonder, though, whether I’m probing or merely projecting whenever I hear some of its chapters. Just to take one example, the piece entitled, “Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott, 381 Days.” It begins with a major-key dirge by Smith’s trumpet, with a tone and tempo reminiscent of such mid-1960s elegiac milestones as Lee Morgan’s “Search for the New Land” and John Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme.” One can easily interpret this table-setting incantation as signaling the no-turning-back-now gesture by Parks in her epoch-making refusal to sit in the back of an Alabama public transport. Then, for several bars afterward, a chugging 4/4 beat, driven by ak-Laff with bouncy strides, conveys the “381 Days” of the resultant boycott, which forced hundreds of domestics, office workers and laborers to walk instead of ride to work and shop, thus representing the first of the era’s significant civil-rights marches.

I’m confident I’ve sussed that out correctly. But when I hear the strains of bluesy strutting at either end of “Thurgood Marshall and Brown Vs. Board of Education: A Dream of Equal Education,” am I being cued to imagine the swagger and bravado of its eponymous heroic lawyer making his way through several litigious hurdles to reach his finish line at the Highest Court in the Land? And would I know enough to respond to such cues if I didn’t know what its title was? Or, for that matter, know who Thurgood Marshall was and the kind of ribald, larger-than-life figure he was?

It helps to know the history behind the music. But it’s not necessary. Because even if you can sense why Smith and his musicians make the choices in what they play and how they extend their ideas (together or separately), it’s the spacious-skies expansiveness of the concept itself, its willingness to do the unexpected – a segment on the “Black Church” that’s all swirling chamber music and no gospel tropes whatsoever – and let you deal with its implications, that allow you to sense that “freedom” is far more than the theme of Smith’s work here. It’s both his method and his objective.

Smith, after all, was forged in the crucible of what, for want of a better description, we still label “avant-garde jazz.” And what would be a better description? There are so many options. Some like “progressive jazz,” though you kind of feel an anachronistic draft when you hear those words. Others cling to such sixties taglines as “New Thing,” “Fourth Stream,” “Outside” and even “Free Jazz,” though some of the renegades of subsequent decades embraced old-school polyphony that kept things flying in fairly close order. Gary Giddins quixotically tried to coin the word, “parajazz” (or was it “Para-Jazz”?) as an all-purpose umbrella. I like it, but I can’t find anybody else who does.

I also like “creative music” — bringing us back to Smith, who was part of the groundbreaking Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) that nurtured and/or inspired such experimentalists as Henry Threadgill, Anthony Braxton, Roscoe Mitchell, Joseph Jarman, George Lewis, Leroy Jenkins and many more. Their music was as idiosyncratic, original and unconventional as they were. Jazz fans who drew their lines at whatever Miles Davis was doing in 1965 (if not sooner) thought the AACM and their kind were too “way out” to even taste. But back in the seventies, I warmed to the freewheeling, sometimes breakneck invention of the renegades. It’s true they made mosaics out of traditional rhythmic pattern and carried thematic ideas down dark alleys and wooded glades you never thought of visiting. But as with avant-gardists of the past, they weren’t upending the order-out-of-chaos imperative of art as much as encouraging listeners to re-fashion or, at least, reconsider their own notions of order. In other words, they weren’t the only ones creating the music; you had to join in the process, too. And where previous generations did so by dancing, we did it by thinking or feeling our way through the changes.

Smith, now 71, has for decades advanced his own vision of creativity into finding new ways of fusing improvisation and notation. (He explains this process in far greater detail here, though, as with his music, one run-through won’t be enough.) Ten Freedom Summers uses the late 20th century’s upheaval to apply firmer context to the process. Those unaccustomed to such compulsively creative composition may think it’s haphazard, even if they know the historical facts being represented or dramatized. But as it was with the avant-garde’s loft concerts of the 1970s or for that matter, some of the late, lamented Knitting Factory’s wilder nights of the 1990s, the whole idea was to listen and to be attentive always for whatever is familiar in one’s own memory, private or public, and for what could be something you never knew before. From such surprises, you can make your own connections to this freedom struggle – or any other such struggle you can imagine. It may well have been this openness to possibility that the Pulitzer committee recognized in almost-but-not-quite giving their top prize to Ten Freedom Summers. If so, then it’s a whole way of thinking about music, and not just jazz, that’s received its just desserts.