IMMEDIATE REACTION: I had a good time. I expected to. I needed more.

By now, unless you’re sticking your fingers in your ears and going “La-la-la-la” whenever somebody brings the matter up, you’ve probably heard that Star Trek: Into Darkness is supposed to be a riff on 1982’s The Wrath of Khan. Either I’m on the wrong meds or more senile than I imagine, but wasn’t its predecessor supposed to be a rejiggered version of Khan? And if so, is this how it’s going to be from now on, all these new actors in old roles and “classic” uniforms replaying variations on the same story (e.g. evil madman seeks apocalyptic revenge for real and/or imagined crimes)?

If so, then I guess nobody wants to make Star Trek movies any more. Because, let’s face it: Into Darkness isn’t a Trek movie. It’s got all the characters from Trek and the actors who play them are all very good; in one, maybe two cases, even better than their predecessors. But it’s more a movie about Trek than it is a Trek movie. It roots around the attic, appropriating old tropes and familiar names to make the devotees nod in recognition. But what I liked most about J.J. Abrams’s 2009 reboot was its impudent intent to make everything new while remaining attentive to the basic enthusiasm for human possibility that made Gene Roddenberry’s franchise linger for so long in the collective unconscious. (From one dedicated, mildly crazed TV show-runner to another…) Abrams’s follow-up, by contrast, seems content to use Kirk, Spock, Scotty and the rest as action figures that serve the corporate model for summer thrillers; most especially, the Great American Multiplex’s persistant yearning for revenge fantasies along with the attendant surges of explosions, kick-boxing, mass carnage and the obligatory, egregious deaths of beloved father figures. (Be warned: I’m going to respect the “NO SPOILERS” mandate only so much. If you care that much about what happens in this movie, you’ve had plenty of time to see for yourselves.)

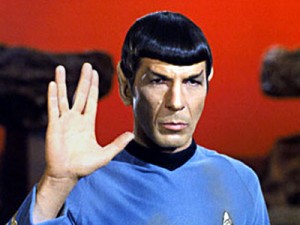

True, I wasn’t bored. Which surprises me since there was so little about In Darkness that was new, either in the plot points germane to the Trek mythos or in the usual heavy machinery assembled for standard-issue popcorn phantasmagoria. In fact, I bet the hard-core Trekkers (sic) had themselves a fine time pointing out all the scenes, set pieces and dialogue that had some connection with any and all of the varied Star Trek TV shows and movies. I bet if they tried really hard — and, trust me, so many of them don’t need to try – the SF-movie savants could point out references to other big-ticket movies in their favorite genre. Independence Day cornered the market on such shamelessness, only no one to this day considers it shameless. (It’s a classic, doncha know?) Whatever you call it, this sampling would be barely tolerable if it weren’t offset by the pleasure you get from watching the cast settle into their retrofitted characters. Chris Pine’s Kirk, though properly brash and impulsive, doesn’t yet have the William Shatner strut, though he seems to be quietly assembling his own brand of hauteur to carry into future episodes. Zachary Quinto’s Spock here shows more of the character’s original diffidence; of all the new actors, he’s the most thoroughly comfortable in his (tinted) skin. I still do not buy the office romance between Spock and Zoe Saldana’s Uhura for a nanosecond, but I am loving how she’s taking advantage of Trek 2.0’s greater breadth and depth of her character’s conception. I wish there were much more of John Cho’s rigorously circumspect Sulu, Anton Yelchin’s super callow Chekov and Karl Urban’s somewhat constrained Bones McCoy. I can’t yet tell whether Abrams and his team aren’t quite into the idea of McCoy, which would be a fatal mistake, or whether Urban doesn’t yet have a handle on him. The writers do seem very fond of the idea of Scotty rendered by Simon Pegg as a puckish grump with overcompensation issues. The revision plays to Pegg’s strengths and I’m guessing this series has bigger plans for him than they do for Urban – which would, again, be a big mistake since Trek’s classic verities are rooted in the tug-of-war between the hyper-passionate ship’s doctor and the coolly rational First Officer.

But I’m no longer sure Abrams really cares about the foundations of the old Star Trek as he does in critiquing, if not subverting Roddenberry’s vision. Let me put it another way: Why bother doing the Khan story, not once, but twice? Is it just to show how you can build a better Enterprise? As much as we love these characters in action no matter who’s playing them, it wasn’t just who they were or what they did, but what they represented to us back in 1966: Hope for the future. We’ve not only made it further out in space, but we seem to have managed to make ourselves better, smarter, more tolerant people. We figured out how to live together so well that we seem to be able to get along with people from other planets without being freaked out by the shape of their ears. Now what? That’s what we came for every week. What do we do with this wider perception of our own humanity as we head out yonder? Just as important, what DON’T we do? What is it about this expanded knowledge that keeps us from acting as stupid as some of the beings we encountered on this five-year mission, human or extraterrestrial?

These are the kinds of questions we counted on science fiction to engage, if not necessarily answer. And while we dug watching Kirk and the crew in all those cool martial-arts matches with Klingons and Romulans, the action sequences were access points for the question we knew Star Trek had to ask at some point every week: What does it mean to be human? Into Darkness is into the action sequences, but they seem placed there to sustain our thirst for retribution, which the movies seem to have been exploiting ever since (I’m going to say) 9/11. We no longer seem interested in seeking new life and new civilizations, but in kicking ass and taking names of those bullies who slaughter innocents and blow up our buildings. This yearning for the big win over terror may be who we are. But is it who we want to be? If Abrams and his co-writers are serious about this five-year mission the Enterprise is about to begin, maybe they’ll allow us to find out. But I don’t hold a lot of hope about this. Maybe that’s who I am.