December 9th, 2018 — jazz reviews

It was the kind of year when the biggest, most-talked-about release in recorded jazz was a compilation of takes and outtakes from fifty-five years ago. It wouldn’t surprise me to see Both Directions At Once at or near the top of some reviewers’ lists for best new album since its 1963 sessions by the John Coltrane Quartet had never before seen the proverbial light of day. The album doesn’t appear on this list, and I’ve already suggested why it won’t. Still it was the kind of marketing triumph rarely seen in jazz music, pulling in a big, broad spectrum of listeners. Some older jazz heads told me Both Directions drew bigger crowds than Coltrane did when he was still alive – which sounds more than plausible.

Even with my misgivings, it was hard not to be caught up in the excitement Both Directions At Once aroused among listeners, especially those who weren’t yet born when Coltrane died in 1967. Yet along with the excitement there was also a melancholy acknowledgment that Back Then aint the same as the Here & Now. Hearing the Coltrane quartet at a time when some of its greatest breakthroughs were just ahead reminded you that those early-to-mid-1960s were an era of expanding horizons and greater possibility.

And now? To paraphrase something one of my peers told me earlier in the year, we once lived in a time of transcendent, boundary-breaching improvisers. Now we live in an era awash in very-good-to-great players working well and even nobly within the standards set by giants. Every once in a while, one of them spins you around by making a sound you never heard before. (Number 4 on this list has been doing this since she emerged only a few years ago.) But maybe Gary Giddins was right when he wrote back in 1983 about the emergence of the Marsalis brothers and their contemporaries, “My intuition is that innovation isn’t this generation’s fate.”

After almost forty years have passed and at least a couple more of waves of musicians have emerged, Giddins’ assessment still sounds prescient, at least as far as improvisers are concerned. But there are other ways to be innovative. Throughout this period of revision and retrenchment, some of our most interesting jazz artists have devoted their energies to creating or, in Wynton Marsalis’s case, refreshing contexts for jazz’s presentation, whether by expanding the music’s canon through jazz repertory or providing broader frameworks for presenting the music. Maybe you bring choirs along as part of your equipment, as Kamasi Washington does, or revise conventional horns-rhythm-section stagecraft as the late Max Roach once suggested – and as artists such as Esperanza Spaulding have been doing. It’s the same kind of musical nation-building that Miles Davis, Charles Mingus, Art Blakey and Betty Carter used to do with their outfits and I’d like to believe that from these revised contexts, more than a few musicians will emerge and make all our heads spin the way John Coltrane once did, and still does.

Or…I could be wrong. Anyway, here’s my list and I’m sticking with it:

1.) Steve Coleman and Five Elements, Live at the Village Vanguard, Vol. 1 (The Embedded Sets) (PI) – In Coleman’s previous appearances on this list, I’ve described what he and his band are doing as an ongoing quasi-scientific inquiry into what he characterizes as biological processes, but are in reality groove dynamics and harmonic montage. The studio work has yielded encouraging and often earth-shaking results. But in a live setting, especially within the concave confines of jazz music’s Holy Dive, everything the band does seems ramped up in intensity as if having live witnesses to its experiments goads Coleman, Jonathan Finlayson, Miles Okazaki, Anthony Tidd and Sean Rickman to raise their respective games. The overlapping dialogue between Coleman’s scorching alto sax and Finlayson’s slashing trumpet seems more colorfully serpentine on stage while the worlds-within-worlds polyrhythmic drive provided by bassist Tidd and drummer Rickman yanks you into the music’s molten core and Okasaki’s guitar sets off well-timed compression bombs. If your head can move to this group’s percolating dramatic tension – and it should – your body will eventually follow.

2.) Wayne Shorter, Emanon (Blue Note) – This just in: THE MULTIVERSE EXISTS! If you doubt this, and you do so at your peril, you need to find the nearest available copy of The 3 Marias, a “prestigious publication” dominating a “one world reality” known as Logokrisia. Failing that, you’ll just have to trust this one-of-a-kind artifact springing from the teeming brain of a comic-book nerd from Newark who grew up to become, among (many) other things, one of this year’s Kennedy Center honorees. This combination of graphic novel and three-disc collection is a multiverse you can carry around the house or, if invited to do so, somebody else’s. The title, which is “no name” spelled backwards , owes its origins to a Dizzy Gillespie tune and is given to the novel’s mystical superhero. Described by Shorter and co-author Monica Sly as a “rogue philosopher,” this Emanon travels from dimension to dimension to subdue fear and oppression in all its forms and replace them with knowledge and wisdom. The real mystery and suspense come with the music performed on the three discs by Shorter and his comparably intrepid sidekicks, pianist Danilo Perez, drummer Brian Blade and bassist John Pattitucci, spinning off motifs, ideas and even characters from the comic book (“Pegasus,” “The 3 Marias,” “Prometheus Unbound” etc.) The first installment has the quartet deploying its customary allusive interplay in tandem with the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra. At times the combination sounds like the soundtrack to a cryptic SF movie spectacular. But then, almost all of Shorter’s compositions, going as far back as such grandly-conceived classics as 1965’s The All-Seeing Eye and ahead towards such underrated pastels as 1985’s Atlantis (where “The 3 Marias” first appeared) and 1995’s High Life, are soundtracks to movies whose stories would be too inscrutable for Hollywood to attempt. The quartet carries on its sporadic, probing conversations on the other two discs, whose content is culled from a live London concert. Some listeners have complained that the music seems more tentative than they expected as a definitive statement from the greatest living jazz composer. (We’ll argue that latter clause some other time.) But it all sounds pretty definitive to me, coming as it does from somebody whose teenage nicknames were “Mr. Gone” and “Mr. Weird.” Listen to this music often enough and you’ll find that its secrets aren’t meant to be deciphered; only appreciated on their own slippery, shadowy terms.

3.) Charlie Haden & Brad Mehldau, Long Ago and Far Away (Impulse!) – Up until his death in 2014, bassist Haden was always up for melding minds with other individual seekers of beauty and truth. This colloquy, recorded in 2007 at a jazz festival in Mannheim, Germany, may not be perfect (since nothing is), but it is gorgeous in the affecting manner of an early winter sunset or a lingering over-the-shoulder pivot towards a onetime lover you’re certain of never seeing again. Haden knew a fellow romantic sensibility when he met one and Mehldau found in Haden’s generosity of spirit a warm, safe haven for his vagabond lyricism and bold phraseology. The playlist is pure classic standard, from “Au Private” to “Everything Happens to Me,” both of whose steady-as-she-goes renditions here would have made Charlie Parker smile. But what would have caused Bird to sit up straight with wide eyes are Mehldau’s variations within each chord change; sometimes they swirl and tumble onto a different path while at other times they imperturbably ride with whatever tangent Haden discovers along the melody’s surface. These collaborators bring out each other’s richest conceptual contours in such ballads as “What’ll I Do” and a Haden favorite, “My Love and I,” David Raksin’s love theme from the 1954 movie “Apache,” within whose bridge Mehldau shakes loose some of his most stunning inventions, expansive yet firmly tethered to the song’s pulse. Haden has always shown a special watchfulness in piano duets. This one is most remarkable for disclosing many things we either didn’t know, or merely suspected, about Mehldau’s resourcefulness. And, as another entry on this list will attest, we’ve come to know a lot more by now.

4.) Cecile McLoren Salvant, The Window (Mack Avenue) – She can neither be stopped nor contained by anybody’s marketplace; nor is she in any way daunted by having to immediately follow the most breathtaking and ambitious jazz vocal album of this century. She takes a heady gamble on this one by relying mostly on a single accompanist: pianist Sullivan Fortner, who is as formidable a dramatist with his instrument as she is with hers. Her inflections provide well-timed cues for his embellishments and fusillades. Granted, there are times when their respective strengths almost collide, most notably on that Bernstein-Sondheim rouser, “Somewhere,” when their attacks at different ends of the song threaten to shortchange its impact and even confuse their listeners. But even when they threaten to go too far, they end up creating something you haven’t heard before – and won’t mind hearing again. She’s still at the top of her game and, more definitively, her profession. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if I’m talking about her again in this space a year from now. I expect to be surprised by what she chooses to do next.

5.) Charles Lloyd & The Marvels + Lucinda Williams, Vanished Gardens (Blue Note) – “We all play folk music,” Thelonious Monk once told Bob Dylan. Accordingly, this smoke-cured aggregation of laments, dirges and secular prayers lofted towards what we cringe to regard as Present Day Reality feels very much like the album Dylan would release if he believed now was the time to try more jazz with his blues. Led by tenor saxophonist Lloyd, who at 80 seems to be (in Dylan-speak) a lot younger than he was in his Forest Flower period of the 1960s, guitarist Bill Frisell, bassist Reuben Rogers, drummer Eric Harland and steel guitarist Greg Leisz concoct a spectral blend of American musical java that soothes and jolts at odd hours of the day. Williams, in my judgment, has never had more suitable backup for her leathery vocals, whether on original songs such as “Ventura” or “Unsuffer Me” or on Jimi Hendrix’s “Angel” on which you’re tempted to imagine an alternate reality where he lived long enough to accompany her. (Maybe Wayne Shorter, or Emanon, can find one.) Still wondering why “Ballad of the Sad Young Men” is an instrumental, but they (whichever [sic] “they” are) may know something I don’t.

6.) Joshua Redman, Still Dreaming (Nonesuch) – Jazz needs another tribute album the way I need another Bush, Clinton or Trump to run for president. But this feels far more like an urgent personal testament than yet another solemn salaam to a past master. It’s a tribute, perhaps foremost, to Redman’s father, which also makes it a homage to the Old and New Dreams band that featured Dewey Redman on tenor, Don Cherry on trumpet, Charlie Haden on bass and Ed Blackwell on drums. And because that group was formed as a kind of early exemplar of an Ornette Coleman repertory band, the younger Redman, Ron Miles, Scott Colley and Brian Blade are taking on the respective roles of the aforementioned (now departed) players, but in their own voices and on their own terms. Thus, these four guys aren’t paying homage so much as paying renewed attention to a state of mind, a manner of behaving well under pressure and a means of stretching the collective unconscious. There is one piece each by Haden (“Playing”) and Coleman (“Comme Il Faut”). Yet most of the compositions are originals by Colley and Redman, the latter of whom, despite the fearsome range displayed in his previous recordings, shows sweet affinity with the serrated rhythmic patterns and riff extensions of the older band. It’s hardly a secret that all was not well between the elder Redman and his son in the former’s lifetime. But the peaceful feeling one gets listening to these tracks suggests a more intimate, profoundly deeper peace fully achieved within a tumultuous heritage of undaunted dream weavers.

7.) Brad Mehldau Trio, Seymour Reads the Constitution (Nonesuch) – To get the obvious out of the way, yes, I was intrigued, though mildly disappointed to find out that the title tune refers to a dream Mehldau had wherein the thirsty-grizzly voice of the late Philip Seymour Hoffman was reading the Constitution to him. But it wasn’t the only reason I couldn’t keep this disc out of my player for most of the calendar year. By now, the things Mehldau has done to stretch possibilities of the piano trio format have become part of the music’s turn-of-the-century heroic folklore. But what keeps us attentive to Mehldau and his longtime partners Larry Grenadier (on bass) and Jeff Ballard (on drums) is their expansion of jazz’s repertoire, either by broadening the definition of “classic pop” (Brian Wilson’s “Friends,” Paul McCartney’s “Great Day”) or by prying open fresh approaches to modernist standards, especially Sam Rivers’ evergreen “Beatrice,” whose natural bounce is refreshed here with insouciance and ingenuity. To his own compositions, Spiral” and “Ten Tune,” Mehldau brings deeper harmonic invention and tonal progressions that reflect the abiding influences of both Bach and Brahms. Somehow, Mehldau has softened his intensity without losing his edge and still stands out among a prodigious — and increasingly crowded — pack of great jazz pianists.

8.) Christian McBride’s New Jawn (Mack Avenue) – “Jawn” is Philly-speak for…well, I suppose if a definition of a noun is person, place or thing, then “jawn” is another word for “noun,” though I always took it as a Del-Val variant of “joint.” In any event, I don’t think McBride’s piano-less quartet necessarily qualifies as a “new thing,” which for jazz heads of earlier generations was a euphemism for what was considered avant-garde from roughly 1959 till 1971. In fact, there’s something bracingly familiar in this joint’s blend of freewheeling neo-bop and nimble rhythm machinery. Trumpeter Josh Evans and saxophonist Marcus Strickland let fly with seeming abandon while staying grounded to the shifting pocket of percussion lad down by drummer Nasheet Watts and the bassist-leader, who despite his growing reputation as an eminence-gris on his instrument still comes across as the young tyro breaking loose from Philadelphia’s storied Settlement Music School. And perhaps what’s most gratifying about a small ensemble such as this is that it provides an ideal showcase for hearing what McBride has learned and can teach as a musician and a leader.

9.) Eddie Henderson, Be Cool (Smoke Sessions) – Let me tell you about Eddie Henderson because his is one of the most remarkable jazz-life stories you probably never heard. First of all, it’s Doctor Eddie Henderson, having earned a medical degree from Howard University in 1968 four years after earning a B.S. in zoology from Cal-Berkeley in 1964. His general practice came in pretty handy in the years after he’d recorded with Herbie Hancock’s Mwandishi electro-boogie band in the early 1970s. Oh, and before all that happened, he took his first trumpet lesson with Louis Armstrong at age nine. This was in large part because he came from Harlem entertainment royalty since his mother was a Cotton Club dancer and his father was a singer whose 1957 cover of “I’m Gonna Sit Right Down and Write Myself a Letter” was a million-seller. If that sounds like too much to take in at once, then we’ll make this long story short by saying that Dr. Henderson continued to practice general medicine while playing, recording and touring all over the world. This latest album of polished hard bop, backed by solid gold players such as pianist Kenny Barron, alto saxophonist Donald “Big Chief” Harrison, bassist Essiet Essiet and drummer Mike Clark, comes across as the closest thing to a musical autobiography Henderson has put forth so far. Its selections pay homage to players who have inspired and nurtured him throughout his long career whether it’s Hancock (“Toys”), Coltrane (“Naima”), and fellow trumpeters Woody Shaw (“The Moontrane”) and Miles Davis (his take on “Fran Dance” just misses equaling Davis’ dry-witted studio rendition from 1958, but that’s OK because Miles never quite matched it either and Henderson’s comes closer than he did). But what boosts this testament towards rare air is its approach to that stout old warhorse, “After You’ve Gone.” Most interpretations play that Tin Pan Alley ditty as a briskly paced taunt. Henderson, however, goes against the grain and slows the tempo, turning what’s popularly recognized as a jolly anthem of comeuppance into a wistful rumination on loss. I forgot to mention: Henderson turned 78 last October and is still gigging, recording, broadening his musical horizons and, for all I know, available for consultation.

10.) Noah Baerman Resonance Ensemble, The Rock & The Redemption (RMI) – The notion of a jazz suite devoted to the myth of Sisyphus seems so obvious that you wonder why it hasn’t happened before now. (Albert Murray, the late philosopher king of swing, had to have at least sketched out an idea of Sisyphus as the first blues hero…somewhere.) It’s likely that the idea was waiting to land on someone like Baerman, a keyboardist-composer who teaches at Wesleyan University and has struggled his entire life with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, an incurable malady that affects connective tissue. As one can imagine, the disorder has tempted Baerman to walk away from playing music, but he has gone on and in doing so, found communion with the dogged Sisyphus, whose labors to roll a boulder up a slippery slope are duly honored with an 11-part piece blending funk, gospel, hard bop and (of course) blues. Baerman’s Resonance Ensemble provides formidable support for this tribute to perseverance: Kris Allen on reeds, Chris Dingman on vibraphone, Henry Lugo on bass, Bill Carbone on drums and vocal support from cellist Melanie Hsu, Garth Taylor, Latanya Farrell and the late Claire Randall, whose murder at age 26 a year after this 2015 recording session became yet another painful marker on the slippery, treacherous slope of day-to-day existence. Her presence here is part of the bittersweet gift this enterprise bestows on those of us who wake up every day with a boulder in front of us, still standing wherever we left it the day before. The way I see it – and maybe Noah does, too – the rock mocks us, but in doing so, its presence reminds us that we’re still alive. And pushing.

HONORABLE MENTION: Orrin Evans and the Captain Black Big Band (Smoke Sessions) Andrew Cyrille, Lebroba (ECM); Luciana Souza, The Book of Longing (Sunnyside); Renee Rosnes, Beloved of the Sky (Smoke Sessions); Jeremy Pelt, Live in Paris (High Note); Fred Hersch Trio, Live in Europe (Palmetto); Don Byron & Aruán Ortiz, Random Dances and (A)tonalties (Intakt); Ambrose Akinmusire, Original Harvest (Blue Note); Dave Holland, Uncharted Territories (Dare2); Matthew Shipp Quartet Featuring Mat Walerian, Sonic Fiction (ESP Disk); Kamasi Washington, Heaven and Earth (Young Turk)

HISTORICAL/ARCHIVAL/REISSUE, ETC.

1.) Frank Sinatra, Only The Lonely (Capitol)

2.) Keith Jarrett, La Fenice (ECM)

3.) Miles Davis & John Coltrane, The Final Tour: The Bootleg Series, Vol. 6 (Columbia/Legacy)

LATIN ALBUM

David Virelles, Igbó Alákoran (The Singer’s Grove) Vol. I & II (PI)

HONORABLE MENTION: Ruben Blades, Wynton Marsalis & Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, Una Noche Con Ruben Blades (Blue Engine)

VOCAL

Cecile McLorin Salvant, The Window

HONORABLE MENTION: Luciana Souza, The Book of Longing

DEBUT

Arianna Neikrug, Changes (Concord)

December 30th, 2016 — jazz reviews, movie reviews, on writing lit -- and unlit, TV reviews

Yes, I know. This happened within the last few days, followed closely by this and then, for God’s sake, this. I still say 2016 isn’t, as so many insist, The Worst Year Ever for high-profile deaths; not in my lifetime anyway.

I checked. Consider 1959, whose carnage all but commenced February 3 with Buddy Holly, Richie Valens and J.P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson crushed and shredded by an Iowa plane crash. There followed the deaths, in no particular order, of Billie Holiday, Errol Flynn, Raymond Chandler, George Reeves, Mario Lanza, Frank Lloyd Wright, Lester Young, George C. Marshall, Carl “Alfafa” Switzer, Victor McLaglan, John Foster Dulles, Cecil B. DeMille, Bert Bell, Kay Kendall, Preston Sturges, Eddie “Guitar Slim” Jones, Ethel Barrymore, Boris Vian, Sidney Bechet, Lou Costello…

Some of these deaths were untimely and unexpected, others weren’t. And go sit in a corner if you even think of responding with something like, “Yeah, but these were all OLD people…”

I can easily pull other, similar examples out of my memory bank, especially Bobby Kennedy’s “very mean year” of 1961 (Ernest Hemingway, Patrice Lumumba, Gary Cooper, Booker Little, Barry Fitzgerald, Dag Hammarskjold, Sam Rayburn, Scott LaFaro, Ty Cobb, James Thurber, Maya Deren, Dashiell Hammett, Grandma Moses, Chico Marx, Jeff Chandler, George S. Kaufman, Carl Jung…) spilling right into the following year (Marilyn Monroe, William Faulkner, Ernie Kovacs, Eleanor Roosevelt, Benny Paret, Niels Bohr, Isak Dinesen, Myron McCormick, Charles Laughton, Franz Kline, C. Wright Mills…) and onwards towards 1966 (Lenny Bruce, Walt Disney, Evelyn Waugh, Bud Powell, Montgomery Clift, Frank O’Hara, Bobby Fuller, Richard Fariña…) and 1974 (Duke Ellington, Earl Warren, Jack Benny, Agnes Moorehead, Ivory Joe Hunter, Frank McGee, Cornelius Ryan, Darius Milhaud, Chet Huntley, Bobby Bloom, Frank Sutton, Cass Elliot, Joe Flynn, Charles Lindbergh, Nick Drake, Richard Long, Cyril Connolly, Gene Ammons, Otto Kruger, Jacqueline Susann, Amy Vanderbilt…)

And I could go on like this forever. Do you know why? BECAUSE SO DOES DEATH, PEOPLE. Once you stop thinking of your own era as being, like, so totally unique, it helps make everything around you less frightening.

Repeat after me and say it over and over at night to help you sleep: Years don’t make us better or worse. WE make years better or worse.

With that in mind, I’d like to submit my own random, totally subjective list of the things that made 2016 not suck quite as much as you might otherwise believe. For one thing, it was, despite the prevailing socio-political landscape, a terrific year for African American culture, as many of the attached items will attest. And that will be as true of 2016 ten years from now as it is now, no matter what state the United States will be in by then:

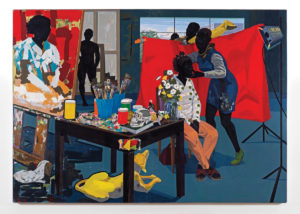

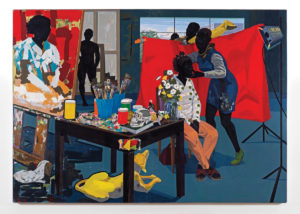

Kerry James Marshall – Along with Wrigley Field, the Billy Goat Tavern and the architectural river cruise, the best part of my late summer trip to Chicago was “Mastry,” a comprehensive exhibition of Marshall’s paintings and drawings at the Museum of Contemporary Art whose breadth and intensity of vision almost brought me to my knees. The exhibition later travelled to New York where it likewise riveted, astonished and inspired millions more. There were many who saw hope with the Cubs’ long-deferred triumph in this year’s World Series. I saw hope and much more in this living Chicago institution.

Atlanta – Donald Glover’s masterly FX series about hip-hop life along the edges validated my long-held suspicions that there was something about its eponymous city that transgresses laws – or at least customs – of time and space. It’s a city where Justin Bieber is magically transformed into the bratty young black man you suspect he’s always wanted to be and where every single plan that an ambitious brother like Glover’s Earn can conceive is chopped up and pureed into unrecognizable, perplexing anomalies. Though he was writing about DJ Shadow this past summer, Greil Marcus could have been talking about Earn and his milieu when he described “a sampler of bits and pieces of dislocation in modern life – finding yourself in the wrong place at the wrong time and realizing you were born there – the textures can seem meretricious, accepting, as if there’s really nothing left to argue against…[But] [b]y its end, yes – you don’t know where you are.”

Mahershala Ali – From Ali’s soon-to-conclude duty as Remy Danton, the lovelorn fixer-for-the-highest-bidder on House of Cards, one sensed coiled steel, contained explosiveness and intuitive graces that this actor could call upon for more daunting challenges. Didn’t take long for him to display these qualities when playing the year’s more conflicted criminals. As Juan, the neighborhood crack dealer in Moonlight, Ali lets you see both the smoldering menace with which he quietly asserts proprietorship over his network of mules and the deep, if enigmatic well of sympathy that allows him to connect with a bewildered, vulnerable boy bullied at home and at school for reasons he can’t fathom. For the smaller screen, Ali brought gray shadows and complex motivations to his portrayal of Cornell “Cottonmouth” Stokes, Harlem crime kingpin and chief nemesis of the bulletproof hero-for-hire in Marvel-Netflix’s Luke Cage. He’s so persuasive at evoking a bad man convinced of his essential goodness that one felt a slow leak oozing out of the whole series after his departure. His dual triumphs make one yearn for more opportunities for Ali to play anti-heroes who can deal with the devil while doing God’s work.

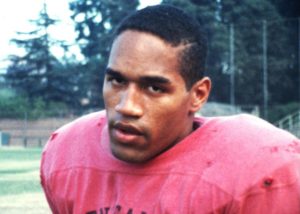

O.J.: Made in America & The People Vs. O.J. Simpson – It doesn’t matter whether you preferred Ezra Edelman’s epochal, illuminating five-part documentary series for ESPN or the Scott Alexander-Larry Karaszewski dramatization which made heroes of erstwhile laughing stocks Marcia Clark (Sarah Paulsen) and Christopher Darden (Sterling K. Brown) without in any way mitigating the scorched-earth genius of Johnnie Cochran (Courtney B. Vance); all of which actors, by the way, won much-deserved Emmys. What both these vastly different approaches to a reverberating crime have in common is what they imply about the glaring inadequacies of day-to-day news coverage. You could argue that all the nuances, subtleties and socio-historical contexts available now to screenwriters and documentarians weren’t as easily accessible to journalists as when the actual Simpson trial was unfolding 22 years ago. But as the last election cycle proved, the 24-hour news cycle, whether on cable or through the Internet, barely bothers even to try thinking such things through. All we’re left with, then and now, are the usual bromides e.g.: It’ll be years before we know what really happened; There’s always more to the story; There’s more here than meets the eye…Blah…Blah…Blah…Whimper.

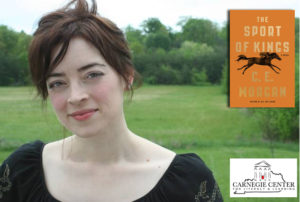

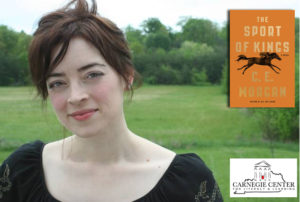

The Sport of Kings – From the great, relatively forgotten, but still very much alive (at this writing) African American novelist William Melvin Kelley, I recently found out that the word “race” derives from the medieval Italian “razzo,” meaning “any given breed of horse.” I’m betting that C.E. Morgan, a intelligent, imaginative and startlingly perceptive daughter of the Bluegrass State, was aware of this arcane connection when she wrote this novel about a Kentucky horse breeder whose attitudes about race roughly parallel those of the odious John C. Calhoun. He has his reasons, of course, and Morgan’s too conscientious a novelist not to take their full measure, however petty they are and however grievous their impact on others’ lives. His venom afflicts two of those lives. One belongs to his spirited, magnetic daughter who shares his obsession with creating the next Secretariat; the other belongs to a black ex-convict from the mean streets of Cincinnati hired to help train this super horse. I’ve pressed and imposed this novel upon others and yet I’ve been struggling to figure out why. One possible answer just now came to me through David Ulin’s retrospective essay about Double Indemnity for the Library of America’s “Moviegoer” site when he cites a quote from the movie’s coscripter Raymond Chandler: “It doesn’t matter a damn what the novel is about…The only writers left who have anything to say are those who write about practically nothing and monkey around with odd ways of doing it.” Self-serving, I suppose, since Chandler’s reputation while alive was that of an innovative genre writer. Morgan’s novel, aiming for higher ground, isn’t about “practically nothing,” but about many things at once. Yet as with great writers of American noir such as Chandler, Sport of Kings surges and leaps heedlessly into big emotions and grand melodrama, which Chandler believed “was the only kind of writing that I saw was relatively honest.” Ulin pushes these points further by defining them as “conventions of the hyper-real.” I haven’t the time or the space here to get into the specifics, but if you can imagine what base-level 20th century American melodrama, whether practiced by realists or “hyper-realists,” can bring to 21st century issues of race and class, then you will understand why I’ve been bullish on this particular horse opera. I didn’t read Sport of Kings so much as submit to its power and it’s been too long since any new novel did that to me. (I was one of the judges who singled Sport out for the Kirkus Book Prize for fiction. If you can call it up, our citation is quoted here.)

The Arab of the Future, Vol. 2 – Along with Art Spiegelman, Roz Chast, Marjane Satrapi, Joe Sacco and the late Harvey Pekar, cartoonist Riad Sattouf has helped establish the graphic memoir as the most innovative and affecting narrative art form to have emerged in the late 20th century. Given the relentlessly bleak news coming out of Syria in recent years, Sattouf, who once was a regular contributor to Charlie Hedbo, may be providing the most timely and poignant contribution with his autobiographical account of growing up between different cultures. In the first volume, avid, adorably fluffy-haired Riad is shuttled back and forth between France, where his mother Clementine is from, and the volatile Middle East of the 1980s where his Syrian father Abdel-Razek embraces the then-burgeoning Pan-Arab movement. In this second volume, covering 1984 and 1985, Riad’s family settle in his father’s hometown of Ter Maaleh as the country reinvents itself under the dictatorship of Hafez Al-Assad. The little boy must adjust to a new school with its fundamentalist dictates, corporal punishment and the usual highs and lows of socializing with other children, complete with bullying of an especially brutal and bigoted kind. In recounting these and other vicissitudes, Sattouf maintains his wit, balance and equanimity towards all his characters, even at their worst. This is especially true of his father, who is by turns insecure, pompous, clueless and frantic to fit into whatever future his homeland devises for himself and his family. As with its predecessor, the second volume of Arab of the Future makes you wonder how long it’ll be before Abdel-Razek’s dreams come crashing down. But even with that dire prospect, the warmth and wisdom seasoning his son’s rueful memories keep you hoping for the best for the Sattoufs while bracing for the worst.

Weiner — It’s odd how some things can both become dated and gain added significance in only a few months. When I first saw Weiner in the theater, it was early summer, Huma Abedin’s mentor was still well-positioned to be the next president and I came away from the documentary thinking mostly about Abedin’s inscrutably slow-burning gazes at the movie’s main subject who, for all his energy and earnest impulses to do good, came across here as he did everywhere else in the last four years: As an incurable narcissist, stabbing himself, scorpion-like, with his own…um…wretched excesses. I saw the film again on Netflix a couple weeks ago and somehow all that tattle-and-buzz about a man, his penis and social media don’t seem all that important when compared with the brazen lies and mendacity we’ve already seen in play so far from the incoming administration. This time around, what was far more important to me were all those brown and black people occupying the periphery of the action who kept shouting at the TV cameras and their enablers to stop yammering about the man’s dickishness and concentrate on what needs to happen in their neighborhoods to make them better. Wouldn’t it be something if this documentary ended up signifying both the peak and decline of the Age of Gossip and Innuendo? As. If.

Lemonade & Daughters of the Dust – It now seems like forever and a day since Beyoncé dropped her “Formation” video into Super Bowl Week festivities the same way you imagine a visitor from the future, unrecognizable to present-day eyeballs, dropping in on the Iowa Caucus. The 24-hour news cycle chewed its immediate impact to tiny bits until there was little left to the astonishment but empty bluster and gaping bemusement. My own reaction was something akin to: Damn. It almost looks as if Julie Dash directed this badboy! Those of us who cherish Dash’s Daughters of the Dust, her gorgeous 1991 cinematic tone poem set in the turn-of-the-20th-century Georgia Sea Islands have spent the intervening years keeping track of her movements and looking for signs that the movie wasn’t forgotten. And while Dash didn’t direct the “Formation” video, or any of the others emerging from Bey’s daring, insurgent album, Lemonade, there were enough resonances from Daughters to summon a movement to get an enhanced edition of the film out and about to art houses throughout the country. Because Daughters occasioned the first four-star review I ever gave as a Newsday movie critic, this convergence of cultural forces was the happiest I can remember.

Hell or High Water – As I’ve babbled to several people till I bored my own self, I wasn’t at all bullish on movies this year. (The worst of the summer blockbusters, in my opinion, gets its definitive raking-over here by the ever-engaging critical thinkers over at HISHE, who once again outclass what they’re critiquing.) I suppose I’m an incurable aficionado of the mid-to-late-1970s wave of gritty American cinema. And while I think this badlands chase thriller from David Mackenzie wouldn’t necessarily stand out among the glorious products of 40-something years ago, it offered elemental pleasures similar to those movies’: a taut-wire storyline that wastes no time; dry, cool dialogue that likewise goes about its business in real time and no-sweat laconic performances that play changes like a cool jazz combo. Coolest and driest of all is Jeff Bridges in his best performance in years as a Texas Ranger in pursuit of bank robbers aggrieved by the economic unpleasantness of recent years. I also quite liked Chris Pine as one of the robbers, though unlike some reviewers I don’t think he quite steals the movie from Bridges so much as shares the win in the end. If you’ve seen it already, you know there’s added implication in that previous sentence. If not, what the hell are you waiting for?

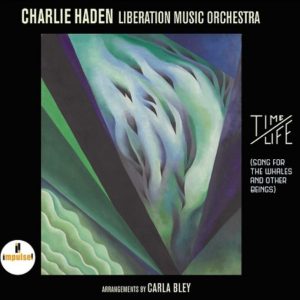

The Liberation Music Orchestra Redux – It all keeps coming back to Chicago at whose jazz festival this year I saw Carla Bley leading the revived Liberation Music Orchestra founded almost a half-century ago by the late Charlie Haden. He’d spearheaded a restoration of the 12-piece band a few years back, but his failing health prevented him from pressing ahead. Bley, who’d been with the orchestra at its creation as both pianist and arranger, picked up the ball and carried on Haden’s dream of focusing the orchestra’s progressive agenda on ecological issues. The Chicago set included pieces from the album Time/Life (Impulse!) whose playlist includes Bley’s multi-textured tribute to Rachel Carson, “Silent Spring,” and Haden’s own “Song for the Whales.” The timing of their return is all-too auspicious and I have a sinking feeling that global warming may soon end up being among many things they’ll be compelled to make music about.

July 23rd, 2014 — jazz reviews

As of this Friday, Charlie Haden will have been off the planet for two weeks. Yet I’m still tripping over him in unexpected places. Earlier this week, for instance, I put on an ECM compilation of Carla Bley’s work and all of a sudden, this voice pours out of the speakers that sounded a lot like Linda Ronstadt’s from her daisy-fresh Stone Poneys days. Turned out that’s exactly who it was: Ronstadt doing lead vocals on Bley’s “Why?” from the 1971 jazz opera, Escalator Over The Hill. And who should be vocally harmonizing with her on this track, in what sounds like the bluegrass idiom of his childhood professional days, but Haden, who also played double-bass for Bley’s orchestra.

As of this Friday, Charlie Haden will have been off the planet for two weeks. Yet I’m still tripping over him in unexpected places. Earlier this week, for instance, I put on an ECM compilation of Carla Bley’s work and all of a sudden, this voice pours out of the speakers that sounded a lot like Linda Ronstadt’s from her daisy-fresh Stone Poneys days. Turned out that’s exactly who it was: Ronstadt doing lead vocals on Bley’s “Why?” from the 1971 jazz opera, Escalator Over The Hill. And who should be vocally harmonizing with her on this track, in what sounds like the bluegrass idiom of his childhood professional days, but Haden, who also played double-bass for Bley’s orchestra.  A day later, I finally caught hold of Last Dance, the recently-released ECM album with Haden and one of his old bosses, Keith Jarrett, performing classic pop standards. Though these duets were recorded in 2007, the album’s ruminative tone and sepulchral title, augmented by having “Every Time We Say Goodbye” and, then, “Goodbye” as back-to-back concluding numbers, seem to emit melancholy prophesy. Except I don’t feel in any way saddened while listening to these intimate conversations between two veterans who, though working with traditional chord progressions and stone-ground rhythms, find new ways to make these warhorses enrapture and inspire. Which may be another way of saying that nothing much has changed and Charlie Haden will somehow always be with us, letting his romanticist’s gospel of Beauty and Truth filter through the world where, through most of his 76 years, he spread this gospel broadly, but never thinly. We could be spending almost as many years wandering through and assessing his prolific contributions as sideman, leader, composer, collaborator and movie director. You read right. Movie director. And while you wont find his name listed as such on the Internet Movie Database, Charlie Haden excelled at making movies of the mind, even when he wasn’t trying. Born in 1937, Haden was a child of both motion pictures and the radio and, thus, instinctively understood how the former so robustly fed people’s imaginations, which were comparably stimulated by the latter. Just as the movies could make you want to get up and dance, orchestrated sounds could make you lie back and dream. By the 1950s, the movies would help dictate how we listen to music. (Think of all those set-the-mood-for-making-out LPs of the era with lush strings.) And Haden became one of the auteurs of concept albums that, openly or otherwise, borrowed their tropes from cinema. Most especially, what became known as the Hollywood noir movies of the forties and fifties became a recurring motif with Haden’s Quartet West albums on Verve, beginning with 1986’s eponymous album introducing the quartet – saxophonist Ernie Watts, pianist Alan Broadbent and drummer Billy Higgins, Haden’s onetime band mate with Ornette Coleman, replaced with Larance Marable on 1988’s In Angel City.

A day later, I finally caught hold of Last Dance, the recently-released ECM album with Haden and one of his old bosses, Keith Jarrett, performing classic pop standards. Though these duets were recorded in 2007, the album’s ruminative tone and sepulchral title, augmented by having “Every Time We Say Goodbye” and, then, “Goodbye” as back-to-back concluding numbers, seem to emit melancholy prophesy. Except I don’t feel in any way saddened while listening to these intimate conversations between two veterans who, though working with traditional chord progressions and stone-ground rhythms, find new ways to make these warhorses enrapture and inspire. Which may be another way of saying that nothing much has changed and Charlie Haden will somehow always be with us, letting his romanticist’s gospel of Beauty and Truth filter through the world where, through most of his 76 years, he spread this gospel broadly, but never thinly. We could be spending almost as many years wandering through and assessing his prolific contributions as sideman, leader, composer, collaborator and movie director. You read right. Movie director. And while you wont find his name listed as such on the Internet Movie Database, Charlie Haden excelled at making movies of the mind, even when he wasn’t trying. Born in 1937, Haden was a child of both motion pictures and the radio and, thus, instinctively understood how the former so robustly fed people’s imaginations, which were comparably stimulated by the latter. Just as the movies could make you want to get up and dance, orchestrated sounds could make you lie back and dream. By the 1950s, the movies would help dictate how we listen to music. (Think of all those set-the-mood-for-making-out LPs of the era with lush strings.) And Haden became one of the auteurs of concept albums that, openly or otherwise, borrowed their tropes from cinema. Most especially, what became known as the Hollywood noir movies of the forties and fifties became a recurring motif with Haden’s Quartet West albums on Verve, beginning with 1986’s eponymous album introducing the quartet – saxophonist Ernie Watts, pianist Alan Broadbent and drummer Billy Higgins, Haden’s onetime band mate with Ornette Coleman, replaced with Larance Marable on 1988’s In Angel City.  The other Quartet West Verves – 1990’s Haunted Heart, 1993’s Always Say Goodbye, 1995’s Now is the Hour and 1999’s The Art of the Song – were more or less pastiches of movie soundtracks, vintage recordings by such diverse artists as Jo Stafford, Jeri Southern, Chet Baker, Billie Holiday, Duke Ellington, Coleman Hawkins and Django Reinhardt. (In the last entry, a full orchestra and singers Shirley Horn and Bill Henderson joined the quartet in the studio.) Critics were mostly enchanted with these discs when they were first released, even though you could hear grousing from some corners that Haden was squandering his considerable energies on studio gimmickry; a kind of “sampling” for nostalgic grownups. But Haden had earned wellsprings of credibility that began to collect around his name in the late 1950s when he’d helped rearrange the furniture in listeners’ heads for all time as a member of Ornette Coleman’s epochal quartet. He’d also put his music where his progressive politics were as founder-leader of the Liberation Music Orchestra and burnished his reputation by helping enhance those of such diverse artists as Geri Allen, Kenny Barron, Hampton Hawes, Abbey Lincoln, Hank Jones, Paul Motian, Bley and Jarrett by sitting in or collaborating with them, live or on record. Whether you dug Haunted Heart or Always Say Goodbye depends on how much you happen to be into the same old movies that Haden was. And Haden’s affinity for Raymond Chandler and other SoCal literary lights was genuine enough to give added integrity and sturdiness to his dreamscapes. Unlike a lot of actual filmmakers, Haden didn’t see those crime melodramas as excuses for ironic reinvention or post-modern hijinks. He thought Chandler and his ilk were funny, incisive and, most of all, relevant enough for whatever present-day reality you inhabit. His perpetual sense of wonder with the sunset-infused landscape of modern jazz and tarnished dreams was infectious – and you were motivated as he seemed to be to imagine your own movies sequences to match the music.

The other Quartet West Verves – 1990’s Haunted Heart, 1993’s Always Say Goodbye, 1995’s Now is the Hour and 1999’s The Art of the Song – were more or less pastiches of movie soundtracks, vintage recordings by such diverse artists as Jo Stafford, Jeri Southern, Chet Baker, Billie Holiday, Duke Ellington, Coleman Hawkins and Django Reinhardt. (In the last entry, a full orchestra and singers Shirley Horn and Bill Henderson joined the quartet in the studio.) Critics were mostly enchanted with these discs when they were first released, even though you could hear grousing from some corners that Haden was squandering his considerable energies on studio gimmickry; a kind of “sampling” for nostalgic grownups. But Haden had earned wellsprings of credibility that began to collect around his name in the late 1950s when he’d helped rearrange the furniture in listeners’ heads for all time as a member of Ornette Coleman’s epochal quartet. He’d also put his music where his progressive politics were as founder-leader of the Liberation Music Orchestra and burnished his reputation by helping enhance those of such diverse artists as Geri Allen, Kenny Barron, Hampton Hawes, Abbey Lincoln, Hank Jones, Paul Motian, Bley and Jarrett by sitting in or collaborating with them, live or on record. Whether you dug Haunted Heart or Always Say Goodbye depends on how much you happen to be into the same old movies that Haden was. And Haden’s affinity for Raymond Chandler and other SoCal literary lights was genuine enough to give added integrity and sturdiness to his dreamscapes. Unlike a lot of actual filmmakers, Haden didn’t see those crime melodramas as excuses for ironic reinvention or post-modern hijinks. He thought Chandler and his ilk were funny, incisive and, most of all, relevant enough for whatever present-day reality you inhabit. His perpetual sense of wonder with the sunset-infused landscape of modern jazz and tarnished dreams was infectious – and you were motivated as he seemed to be to imagine your own movies sequences to match the music.  As fond as I am of the Quartet West discs, I’ve come to believe since his passing that Haden’s greatest achievement as a moviemaker-for-the-mind lies somewhere beyond its body of work. It took me a long time even to appreciate Beyond the Missouri Sky, Haden’s 1996 session with guitarist Pat Metheny as anything more than a decorative collection of spare, wide-open-spacey duets. I am now one with the eighth edition of The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings, which places Missouri Sky among its “Core Collection” rankings. Even as a studio artifact, this album handsomely rewards re-listening with its overdubs and harmonic tracks. Haden’s melodic tone on the bass achieves depth and richness that coax greater fluidity and fineness from Metheny’s playing. The landscapes they evoke have big skies and gilded shadows. The mind movies here are less rooted in genre and more reminiscent of Rohmer or Antonioni in an avuncular mood. The latter didn’t make Cinema Paradiso, but there are nonetheless two pieces from that movie’s soundtrack along with Henry Mancini’s poignant theme from Two for the Road. And it gets even more personal than usual here: Roy Acuff’s “The Precious Jewel,” the mountain folk song, “He’s Gone Away” and Haden’s haunting original hymn, “Spiritual” are clearly intended to be tributes to the bassist’s parents, with whom he’d performed bluegrass and country ballads on radio when he was a little boy. Beyond the Missouri Sky was the first thing I thought of playing when I’d heard he’d died – and the sun was actually setting by the time “Spiritual” had run its course. It was less a funereal experience than a healing one. And I suspect it wont be the last time it will help ease the sting of bad news. After all, the movies he made weren’t distractions. Charlie Haden intended for his music – all of it — to be of use. What else are Truth and Beauty for?

As fond as I am of the Quartet West discs, I’ve come to believe since his passing that Haden’s greatest achievement as a moviemaker-for-the-mind lies somewhere beyond its body of work. It took me a long time even to appreciate Beyond the Missouri Sky, Haden’s 1996 session with guitarist Pat Metheny as anything more than a decorative collection of spare, wide-open-spacey duets. I am now one with the eighth edition of The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings, which places Missouri Sky among its “Core Collection” rankings. Even as a studio artifact, this album handsomely rewards re-listening with its overdubs and harmonic tracks. Haden’s melodic tone on the bass achieves depth and richness that coax greater fluidity and fineness from Metheny’s playing. The landscapes they evoke have big skies and gilded shadows. The mind movies here are less rooted in genre and more reminiscent of Rohmer or Antonioni in an avuncular mood. The latter didn’t make Cinema Paradiso, but there are nonetheless two pieces from that movie’s soundtrack along with Henry Mancini’s poignant theme from Two for the Road. And it gets even more personal than usual here: Roy Acuff’s “The Precious Jewel,” the mountain folk song, “He’s Gone Away” and Haden’s haunting original hymn, “Spiritual” are clearly intended to be tributes to the bassist’s parents, with whom he’d performed bluegrass and country ballads on radio when he was a little boy. Beyond the Missouri Sky was the first thing I thought of playing when I’d heard he’d died – and the sun was actually setting by the time “Spiritual” had run its course. It was less a funereal experience than a healing one. And I suspect it wont be the last time it will help ease the sting of bad news. After all, the movies he made weren’t distractions. Charlie Haden intended for his music – all of it — to be of use. What else are Truth and Beauty for?