How lucky it was for the world-at-large that John Birks Gillespie came to decide at an early age that staying in Cheraw, South Carolina would be stultifying at best, hazardous at most to the health and fulfillment of a quick-witted, smart-alecky young African American. (“Probably I’d have been lynched,” he told me many decades hence.) When one thinks of what the Artist Known Forever as Dizzy did for both his country’s musical and intellectual life as well as for the sounds of Latin and South America, you recognize how irreplaceable he was to the 20th century.

And yet…there doesn’t seem to be as much hype for Dizzy Gillespie’s 100th birthday (Oct. 21) as there was for Ella, Billie, Monk and others whose centennials have been duly, even conspicuously observed. The modernist energies he seized and came to embody in the middle of the last century seem to have been either taken for granted, if not dismissed altogether at the start of this one. Maybe it’s also because Gillespie, for all his myriad accomplishments and innovations, carried throughout his 75 years (he died in 1993) a warm and accessible persona so widely known that it left behind relatively little in the way of mystery or mystique. It could also be that his legacy was so variegated as to make it difficult for those in its wake to properly apprehend its range. “How do you hug a mountain?” the late great jazz columnist Nels Nelson rhetorically asked in his Philadelphia Daily News eulogy.

Approaching the mountain at whatever angle is the obvious way to begin. And that means sifting through a half-century of recordings now scattered to the four winds of the digi-verse. Bebop, which Gillespie helped create and then coordinate to an aesthetic capable of speaking many languages, still has a lot to teach Hip Hop, as the brightest of artists in both camps well know. And Dizzy’s vast corpus of recoded output still speaks, rhymes, cracks wise and inspires those unfamiliar with, or hesitant to sample its glories.

So without further ado, here’s an informal and, yes, highly subjective starter set accessing some of more rewarding landmarks along the great wide Dizzy-Verse. And why waste your time, or mine, getting to the purest, richest lode of all?

THE INDISPENSIBLE

The Complete RCA Victor Recordings (2 CDs) (Bluebird) – Look no further than these as a place to start. The earliest tracks go as far back as 1939 when Gillespie, somewhere between 21 and 22, was flashing his nascent chops for bands led by Teddy Hill and Lionel Hampton. But the molten core of this collection comprises the 1947-1949 sessions of his 16-piece orchestra. People arch their eyebrows when you used the “force of nature” to describe anything or anybody (as they should). But as I’ve written once before of these sessions: “It is still possible to listen to the powerful recordings made by Dizzy Gillespie and his Orchestra in the late 1940s and feel everything around you transformed. What Orson Welles did for movies in Citizen Kane, Gillespie did for big band jazz.” (Do I overstate? I didn’t then, and I don’t now.) It was here that Gillespie’s lifelong inquiries into the force and applications of the Latin beat took hold with the gifted and ill-fated singer and percussionist Chano Pozo (1915-1948), who brought his congas to a pair of especially auspicious recording sessions in late December, 1947 that yielded, among other glories, George Russell’s “Cubano Be/Cubano Bop” tandem, Tadd Dameron’s “Good Bait” and the timeless “Manteca.” It was also here that the three-fourths of what would become known as the Modern Jazz Quartet with pianist-arranger John Lewis, drummer Kenny Clarke and vibraphonist Milt Jackson pooled their resources. Fans of traditional swing bands complained that this music was more difficult to dance to than what they were accustomed. And you may not move right away, mostly because you’re absorbing the hard, galvanic impact of what you’re hearing. But this music moves as surely as the Earth, the clouds and the fastest combustible vehicle you can imagine. The vinyl edition of these sessions is harder to find than this, but if that’s what you happen to value, it’s worth the effort.

And speaking of hard-to-find vinyl:

Dizzy Gillespie: The Development of an American Artist, 1940-1946 (2 LPs) (Smithsonian Collection) – Released in 1976, when the Smithsonian Institution’s jazz division, then curated by Martin Williams, was compiling and releasing intelligent and comprehensive archival recordings deep into the next decade. This one was especially revelatory for the steady-rolling insight it provided into Gillespie’s growth from callow swing insurgent to ringleader of the bebop cabal. The very first track, “Pickin’ the Cabbage” from 1940, was recorded when Gillespie was a member of the Cab Calloway Orchestra’s trumpet section and you can hear in its chord changes and fundamental design the genesis of what would later become in its first incarnation, “Interlude” (also included here in a track featuring a young Sarah Vaughan) and then, “A Night in Tunisia.” There’s a lot of ingenious connection-of-dots here: Two takes of the “Kerouac” tracks spun into thin air and fired into the din of Minton’s Playhouse in 1942 — and yes, it’s named for THAT Kerouac, who was an habitué of those groundbreaking sessions also memorialized by Ralph Ellison in his 1959 essay, “The Golden Age, Time Past.” You also hear what’s been called Gillespie’s first truly “modern” solo on 1942’s “Jersey Bounce,” with Les Hite’s and, from that same year, a track from the Lucky Millinder Orchestra, “Little John Special,” written by Gillespie and containing a horn-section riff that sounds like the spark for what became “Salt Peanuts.” All these important and still-sweet-swinging tracks have been scattered on several discs since this went out of print and never received the digital-transfer treatment. Ken Burns Jazz: Dizzy Gillespie (Verve) is as easily available a default option as any other you’ll come across.

DIONYSUS & APOLLO

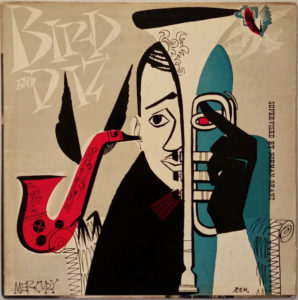

Or, if you will, Bird and Diz (Verve), who some might consider the Janus headed progenitor of modern jazz music. The partnership of Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker was transformative. The friendship was, saying the least, fraught. Yet they were able to subdue personal differences for this 1950 session, where they were joined by the comparably incomparable Thelonious Monk and backed by bassist Curley Russell and the (seemingly incongruous, but not as much as you’d expect) drummer Buddy Rich. If you prefer downloads, then “Bloomdido” is the only track you really need from this session, though the rest is pretty good, too. If you want to hear them at their mutually-assured best together, then seek out Dizzy Gillespie/Charlie Parker: Town Hall, New York City, 1945 (Uptown), which wasn’t released until sixty years later and yet somehow sounds as fresh and up-to-the-minute as last month’s GNP report.

GEMS FROM HIS GILDED AGE

Jon Faddis, Gillespie’s protégé and still the most authoritative keeper of his mentor’s flame, has said that the recordings Gillespie made in the late 1950s and early 1960s represented his peak as a performer and a bandleader. I’ve always thought so, too, though The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings begs to differ with both of us, calling Dizzy’s Verve output from that period spotty at best.

Nevertheless, it’s now hard to find anybody who doesn’t like Birks Works: The Verve Big-Band Sessions (2 CDs, Verve), composed of sessions from 1956 and 1957. The orchestrations here may not be as explosive as they were about a decade before. But his roster was even more star-studded with Benny Golson, Lee Morgan. Phil Woods, Melba Liston, Wynton Kelly, Al Grey, Ernie Wilkins and many others passing through these portals and bringing joy, wit and verve to audiences throughout the world as most of these folks also were with Gillespie on his global good-will tours of the mid-fifties. Lately, I’ve been hearing more tracks from this collection circulating through what broadcasters market as “Real Jazz” or “Classic Jazz” stations on satellite or FM radio. So I suppose this is where most novices now start with Gillespie. I still favor the RCA sessions, but this may be the orchestra’s most purely enjoyable set from start to finish – which is saying something.

Gillespiana (Verve) – At the dawn of the New Frontier (literally the week after JFK was elected), the Gillespie orchestra seemed irradiated by a jolt of energy provided by a 28-year-old Argentine pianist-arranger named Boris Claudio Schifrin, who went by the name, “Lalo.” Previously an arranger for Xavier Cugat’s dance bands (many of whose albums were in Ralph Ellison’s record library), Schifrin sat in Gillespie’s piano chair as the band recorded a five-part suite, “Gillespiana” that he’d written four years before. Once again, a Gillespie orchestra summons fearsome power and breathtaking propulsion. The music on “Gillespiana” starts at a peak and somehow manages to go higher and faster from there. How could we not want to go the moon after hearing something like this? On the CD version, there’s also a Carnegie Hall Concert by the same band recorded six months later (in March, 1961) and even with luminaries as Clark Terry, Ray Baretto and Gunther Schuller (!) on stage, the star of the show, besides the leader, was saxophonist Leo Wright whose solo on “This Is The Way” is one of the more extraordinary live recitals of an era where Carnegie Hall seemed to make history every week.

DIZZY AT PLAY

I concede that the scale on this list is heavily tipped towards the big bands over the small groups. But you really can’t go wrong with any of them. An Electrifying Evening with the Dizzy Gillespie Quintet (Verve), for instance, was recorded in February, 1961 (that same “dawn-of-the-New-Frontier” streak) and benefits mightily from having both the aforementioned Schifrin and Wright in the combo, though the leader doesn’t engage in too many of the on-stage hijinks for which he was famous. (“Let me introduce the band,” he’d say and all the guys on stage would shake hands with each other. You think that didn’t get a laugh every time? Think again.) If I have a guilty pleasure among the chamber Dizzys, it’s Dizzy Gillespie & the Mitchell-Ruff Duo (Mainstream/Sony Legacy), a 1971 live concert at Dartmouth College in which Inspector Diz matched wits with pianist Dwike Mitchell and bassist-French horn-ist Willie Ruff. With no trap set or congas pushing him from behind, Gillespie’s horn seems ever more emboldened as it probes and tugs along the edges of “Con Alma” and “Woodyn’ You” to release fresh, lucid inventions into the atmosphere.

Finally to send you happily on your way (as Gillespie never failed to do), I leave you with this reminder of how popular, how familiar a figure he was in the popular culture firmament. Bebop lived even in places you didn’t expect. Maybe someday it will live like that again.