March 22nd, 2018 — movie reviews, on writing lit -- and unlit

THE MOVIE

Before she began directing films, Ava DuVernay publicized them – and was very good at her work. No surprise then that her adaptation of A Wrinkle In Time is, at the very least, a triumph of promotion. She was all-but-unavoidable on media outlets leading up to the movie’s release — and she’s still selling the movie even while it’s playing in front of you. The theatrical screening I saw opens with a message from DeVernay welcoming the audience, very much in the manner of Disney’s vintage TV anthology series Wonderful World of Color whose weekly offerings often began with Uncle Walt himself handling the introductions to whatever story or animated mélange would ensue over the next hour.

DuVernay’s Wrinkle In Time is a movie that continues to promote itself throughout. Almost every character in the movie is in the act of persuasion whether it’s Alex Murry (Chris Pine), the astrophysicist-dad obsessed with finding a means of “shaking hands with the universe” through psychic dimensional travel, his precocious young son Charles Wallace Murry (Deric McCabe) who somehow seems to know where and how to find his dad who went missing somewhere in the cosmos and the trio of spectral women (Oprah Winfrey, Reese Witherspoon, Mindy Kaling) who are trying to convince Charles Wallace’s implacable, mercurial older sister Meg (Storm Reid) that they are best equipped to lead the way past the dark, insidiously transient cosmic evil – Camazotz– that threatens to swamp everything in dread and rage. The movie sidesteps the novel’s religious underpinnings to promote a broader, more secular means of transcendence: Be brave, be daring, be empathetic, be a “warrior” for peace, love and understanding. etc. The lyrics to Earth, Wind and Fire’s “Shining Star” just about cover it and the anthem’s forty-plus years of existence may account for its being kept off the movie’s pop-loaded soundtrack.

If the overall spirit of DuVernay’s movie intends to prod its audiences to buy into what its selling, then most of its critics thus far are like Meg: grouchy, withholding and not terribly happy with the terrain. The Wall Street Journal’s Joe Morgenstern characterized DuVernay’s Wrinkle as “a magical mystery tour minus the magic and mystery” while New York magazine’s David Edelstein found the movie’s gaudy visual effects suffused with earnest talk of self-fulfillment and uplift adding up to little more than “a transcendental guidance counselor’s movie.” Even some of the more positive reviews, all of which laud the movie’s big heart and open mind, were muted; Richard Brody of the New Yorker thought the movie captured the story’s “sense of exhilaration and wonder” while lamenting that the script “eliminates the most idiosyncratic aspects of the novel.”

Brody, by the way, is so taken with the novel after reading it as an adult that he wishes he’d come across it earlier in life. He’s not the only one.

THE BOOK

The copyright year is 1962. This would have placed me somewhere between nine and ten years old when A Wrinkle In Time was published. I might have been a shade too young, then, to easily connect with all the references made to tesseracts and other matters related to numbers and physics. I say “maybe” because in that year especially I was deeply invested in space travel and, by extension, in the possibilities of inter-dimensional travel.

Such interests, however, refused to keep pace with my affinity for what was then known as arithmetic. Both parents and teachers were at a loss to figure out how this disparity could be reconciled, especially in what was then known as junior high school. (Question for Further Study: Is boredom with school a requisite for underachievement? Discuss – and try to keep up with the rest of the class.)

Probably, then, not that year; but more likely the next couple of years when my solitary romance with time and space only intensified would have yielded more fertile ground for my fascination with Meg and her travels.

More likely, it would have been Meg’s travails that could have drawn me into the center of Madeleine L’Engle’s wheelhouse. By 1965, I would have been the same age as Meg and, thus, better able to relate to her as someone who, like me, had a head that was way too big for the rest of her body; someone who was also spectacularly uncoordinated, socially awkward and prone to wildly annoying behavior to overcompensate for low self-esteem.

The older person I am now reads L’Engle’s breakthrough novel far removed from the emotional cacophony of adolescence and assesses it as the hypothetical outcome of an Italo Calvino’s spin on an L. Frank Baum story idea as rewritten by Rod Serling – which is in no way a dismissal. In fact, one wishes Serling could have written as tautly as L’Engle does without shortchanging his patented sentiment.

Still, in the end, I don’t really know whether reading Wrinkle would have made much of a difference when I was Meg’s age because by that time, other fantasy authors with an older demographic (Bradbury, Sturgeon, Beaumont) were pulling me away from the YA label in libraries; so far away, by then, that it’s likely I would have thought the book too light and airy for the tougher, more lyrical things I was dipping into by Grade 7. But if the multi-cultural casting has done anything at all, it’s made me wonder how it would have affected my own adolescent conduct. Likely such questions would never have occurred to me if DuVernay hadn’t had a say in such casting.

That said…

THE MOVIE, AGAIN

To sum up my own apprehensions going in: I thought it was the most amazing luck that Ava DuVernay decided not to direct Black Panther because I don’t think she’s as good as others believe/hope she is. I supported Selma not because I thought it was great filmmaking (it wasn’t), but because it was necessary to have a movie that prominently placed its black characters as actors in their own deliverance as opposed to just about EVERYTHING of its kind made and distributed by Hollywood beforehand. I was also disappointed by The 13th because I thought it was more of a big fire-breathing billboard populated by talking heads than a documentary that made the necessary deep dives into the political intricacies behind crime bills & other initiatives that made “The New Jim Crow” possible.

She’s better here, but as with Selma the actors save her bacon, especially Ms. Reid, who holds together this thing pretty much on her own and is, I think, a real find; almost as good in her way as Mary Badham was in To Kill a Mockingbird. But Robert Mulligan was a more adroit director of kids than just about anybody who was a better director of movies than he was (if that makes any sense) and, from the way she directs the other kids, DuVernay is no threat to that reputation. Directing McCabe’s Charles Wallace, especially, requires the kind of imaginative approach to human behavior that DuVernay does not have at her disposal. If she had, she’d have dodged the trouble she’d gotten into over her characterization of LBJ in Selma because she’d have better apprehended the full Brobdingnagian complexity of Lyndon B’s personality.

Also for all her engagement with special effects, she doesn’t seem to know how to travel with them. That whole set piece where the kids are riding on the transmogrified back of Witherspoon’s Mrs. Whatsit (or was it Whosit? I lose track) goes nowhere except around the field as if Disney were already planning the ride for one of their theme parks.

Finally, I still can’t quite get over that introduction where DuVernay tells you not only what you’re going to see, but also how you’re supposed to feel at the end of it. This is altogether appropriate for a 50th anniversary of a restored classic. But this is neither an anniversary nor (really) a classic

AND YET…

For all my misgivings, I also understand that this movie isn’t made for me, but for every pre-teen who somehow feels ill at ease under their skins. Which is, last I checked, pretty much all of them. I am hearing of large groups of young people, most of them girls, who leave the movie with moist faces and glistening eyes. I may feel let down by this Wrinkle, but clearly they aren’t. If this is, for many of them, their first encounter with this species of science fantasy, then good on them and the grownups to take them to see it if it leads them to Bradbury, Sturgeon, Richard Matheson, even Phillip K. Dick, though if it were my pre-teen, I might tell her to wait just a little bit for that one.

AND SO…?

As of last weekend, Wrinkle in Time made up little more than half of its $103 million budget. This is leading some to say the “F” word (“flop” or “failure,” depending), though I think it’s still too early. There’s always the possibility that, as with most such movies with very tight close-ups stacked like cordwood, the smaller screen may be a hospitable place for DuVernay’s Wrinkle. Until that happens, let’s, shall we, stop comparing this to that other Disney-produced fantasy-adventure directed by an African-American. Neither Black Panther nor A Wrinkle In Time should be viewed as ultimate referenda on the economic efficacy of black American filmmaking. Things may have changed as much as Panther’s success indicates. But life goes on and memories are short. Unless, that is, you’re an impressionable 9-12-year-old whose horizons need raising. She can – and likely will – do far worse than take Wrinkle into her heart.

December 20th, 2013 — movie reviews

Can anybody make a serious, imaginative movie about slavery without being either ignored or picked at? Quentin Tarantino spent almost as much time shaking off flak for his flamboyant genre goof Django Unchained as he did taking bows and counting money. When Jonathan Demme made Toni Morrison’s Beloved into a far-better-in-hindsight movie in 1998, not even the Great and Powerful Oprah’s approbation of, and involvement in its production could make black people assemble en masse to see it when it was released. (Or anybody else. The cost was about $58 million; the movie made about $23 million, at best.)

At least, nobody’s ignoring 12 Years a Slave. It’s at or near the top of just about everybody’s year-end list of best movies. As of the second week of December, it’s made more than $35 million in American ticket sales with more expected around the bend in advance of Oscar season. Still, the movie has attracted its own high-visibility flak from such critics as Armond White, who believes Steve McQueen’s often-graphically violent rendering of Solomon Northrup’s testament as “torture porn” and “less a drama than an inhumane analysis.” David Edelstein, though he believed the movie “smashingly effective as melodrama,” is less fond of McQueen’s “cold, stark, deterministic” approach to the material.

For the record, I admired 12 Years a Slave far more than I loved it. An American/Hollywood director, no matter how smart or savvy, wouldn’t have trusted as much visually as McQueen does here. (In case you didn’t know, he’s black and British.) He isn’t afraid of stillness, of the tension and energy that reside in the act of waiting, as in the first frame, which in just showing the barely contained anxiety in the faces of slaves, gets the movie moving. That said, I doubt very much I will want to see it again. Do I need to watch, once again, a thin young woman getting whiskey tumblers thrown at her head and then having her back stripped of her ebony skin the way you strip a tree of its bark? I do not – and part of me wonders who would, or who needs to.

Still, because the movie is directed by a black man and is written by another (novelist John Ridley), 12 Years a Slave doesn’t get the same mauling Steven Spielberg’s Amistad (1997) received in some precincts for making ciphers of its mutinous African slaves and using their rebellion as a vehicle for white nobility. And I doubt very much the contrarian attacks on McQueen and his film will keep it from winning more awards; any more than Django’s critics kept Tarantino from collecting a screenwriting Oscar.

But no amount of gold statuettes will stop the haters from jumping on the next filmmaker who wants to take yet another hard, idiosyncratic shot at America’s Original Sin. The only solution: Take more shots, make more movies, go as odd, off-base, strange, funny, stern, cold, hot or heavy as the market can bear – and then, if you’ve got the gall, go further than that. There’s no dearth of material to draw upon, from the still largely undiscovered country of slave narratives to contemporary fiction by African American writers who are claiming autonomy over their ancestral experience through daringly imaginative means.

You like lists. Here are places to go for such material:

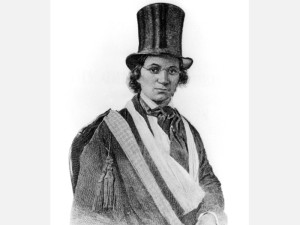

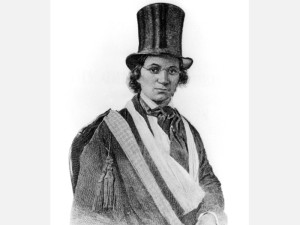

William and Ellen Craft – True story: They were married in bondage in 1846 and escaped two years later from Georgia to Philadelphia in disguise; she (above) as an invalid white man and he as “his” valet. It would take someone with an equally attuned ear for both injustice and comedy, but it could be done.

The Good Lord Bird – Being this year’s surprise National Book Award winner, James McBride’s picaresque comic saga of a young slave boy mistaken as a girl by abolitionist John Brown has likely attracted a few cautious glances from Hollywood. Sophisticated historical satires aren’t exactly meat-and-potatoes fare for multiplexes, no matter who’s involved. But it would be funny, again, if the right tone is struck.

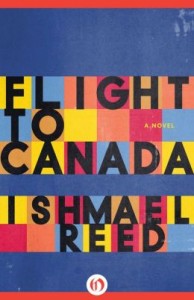

Flight to Canada — An Ishmael Reed seriocomic pastiche that’s never received the credit it deserves for initiating a wave of black novelists claiming imaginative autonomy over their ancestral past in daring, often incendiary fashion. I can’t begin to imagine who would make a movie out of it or what kind of movie it would be. But whenever or however it’s done, it’ll be different from anything that came before.

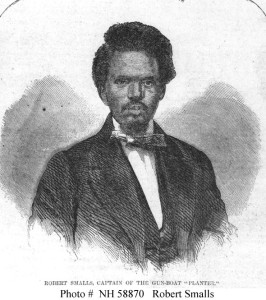

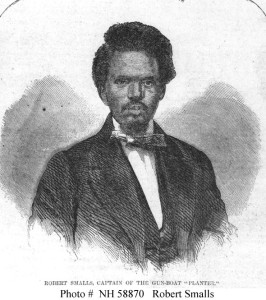

Robert Smalls Steals a Rebel Ship– Another true story; this one about a slave (above) who in 1862 commandeered a cotton freighter with a crew of 17 fellow escapees and managed to hide his identity from Confederate checkpoints, even Fort Sumter, towards the open sea until he was able to raise a white flag to Union blockaders. That alone would be a good movie, though it was just the beginning for Smalls, who later became one of the few African Americans to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives during Reconstruction. (Speaking of which, don’t you think that by now, some great movie about black folk during Reconstruction could be made to counter that damned Birth of a Nation? Just add it to the wish list.)

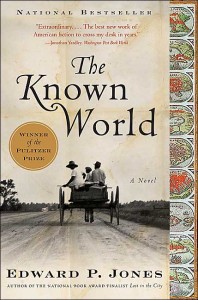

The Known World – Edward P. Jones’ award-winning novel about blacks owning black slaves already made readers’ heads spin off their necks. A movie version could magnify the shock-and-awe and I’m being REALLY optimistic when I say it could be done. But I’m betting it wouldn’t cause nearly as much trouble as…

The Confessions of Nat Turner – And, yes, I mean William Styron’s version, which has been cherished and despised in near-equal measure by black and white readers alike. America wasn’t ready for Turner in the 1830s and they still aren’t ready for him in whatever form he’s presented or imagined. Which doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be attempted.

Middle Passage and Oxherding Tale — A pair of thinking-person’s ripsnorters by Charles Johnson; the former, as with 12 Years a Slave, puts a freed slave in harm’s way as he finds himself aboard a raucous slave ship heading back to Africa to pick up more “chattel.” The latter chronicles the adventures of a half-white-half-black slave negotiating his way through both worlds with philosophic insight and canny resourcefulness.

Kindred — Let me quote from an Amazon review of the late Octavia Butler’s breakthrough SF novel: “Dana, a black woman living in Los Angeles in 1976, is inexplicably transported to 1815 to save the life of a small, red-haired boy on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. It turns out this small boy, Rufus, is one of her white slave owning ancestors, who she knows very little about. Dana continues to be called into the past to save Rufus, and frequently stays long periods of time in the slave owning South. The only way she can get back to 1976 is to be in a life threatening situation.” How is this NOT a movie waiting to happen? Why hasn’t it happened by now?

And on and on and…

August 27th, 2013 — movie reviews

As of this week, a half-century will have passed since the March on Washington took place. As of today, a black man is president of the United States and the number one movie in America is about a black man who spent most of his life as a White House butler. You’d have to be some manner of lunatic to claim this doesn’t show that things have changed mostly for the better since the summer of 1963. You’d also have the mind of a rock to assume that this means the game is over, the Dream is Reality and some other uptight ninny wont decide to stalk Forest Whitaker in an upscale grocery store again.

Whenever stuff such as the incident obliquely referred to above pokes into view, some fluffernutter in public office or on TV uses it as an opportunity to encourage bemused spectators to engage in a “conversation about race”; you know, as in: “Just talk amongst yourselves about this race stuff so that we can keep a dialogue going and somehow that dialogue will keep us from being embarrassed when more prejudiced people are caught in the act of being themselves, etc. etc. etc.”

Just so we’re clear: “Race” is, at best, an abstract concept. Abstractions, at best, make people uneasy because abstractions are difficult to grasp as tangible subjects for whatever it is we humans consider “conversation.” Huge abstractions, such as “peace,” “war” or “race,” aren’t topics for conversation so much as occasions for speaking, mostly in public forums such as legislative chambers, TV studios or glandular discharges on the Web, whether as status updates or blogs like this.

In other words: You don’t “talk” about “race.” You “speak” about it. When you “talk,” it’s mostly about your parents, your jobs, your kids; the stuff they learn (or don’t); the stuff you read (or misread). You “talk” about what you overhear, or pretend not to hear. You “talk” about the shabby way you’re treated in a checkout line, or on an airplane or during an otherwise normal workday. Then you “talk” about imagining such things happening to you. If whatever is meant by “race” never ever comes up in these conversations, then somebody’s either hiding or avoiding something because “race” is as unavoidable a subject in American life as it is a vacuous concept. And we’ve always been good at tabling the subject, if not the vacuousness, when it suits us.

That said, Paula Deen and George Zimmerman, along with the build-up to that aforementioned 50th anniversary celebration of the March have helped create an unusual spike in race-related interaction on and off the Internet this summer. So, for that matter, have two movies by African-American filmmakers, Lee Daniels’ The Butler and Ryan Coogler’s Fruitvale Station. Both have provided plenty of opportunities for “speaking” about race. Yet I’ve noticed that when people “talk” about these movies, they do so acknowledging or, at least, suspecting that there are deeper, more complicated aspects to identity and history than whatever shorthand is deployed by popular culture for “race” or even “class” distinction

Fruitvale Station and The Butler go for the gut more than the head in stimulating their responses. But I think both movies achieve their best effects in what they choose not to do to arouse their audiences’ emotions. In Coogler’s case, it’s his resistance to make his doomed protagonist Oscar Grant III (Michael B. Jordan) either a hapless victim or a sanctified martyr. He’s just a serial screw-up making a one-day-at-a-time effort not to leave messes behind wherever he goes. The slivers of hope that are weaved into the last 24 hours of Oscar’s life are made to seem almost as random or as arbitrary as the circumstances leading to his death You could wish or hope he could be more conscientious about the process. But he’s not you or me. He’s a person confronted moment-to-moment, like the rest of us, with options that don’t always reveal their likely outcomes. So when he’s shot to death at the movie’s eponymous BART station on New Year’s Eve 2008, it stuns us more deeply and intimately than it would if the movie were a more overt indictment of racism and police brutality. A symbol or a martyr wouldn’t leave us feeling as devastated at the end as does this movie’s persuasively human Oscar Grant, especially given Jordan’s thoughtful, composed rendering.

The movie’s tough-minded approach is likewise reflected in its portrayal of Oscar’s mother Wanda (Octavia Spencer), who comes across less as the long-suffering black matriarch of predominantly white imaginations and far more as a pragmatic working-class woman who is in constant negotiation with her own heart as to the best way of dealing with her son. Portent and shadow threaten to upend the movie’s levelheaded tone. But that tone wins out; the film’s soft-pedaled humanism maximizes the impact of Coogler’s penultimate blow, reminding everybody who sees the movie that making a sanctified abstraction out of real people like Oscar (and Trayvon Martin and many others like them) is as heinous a crime as what happened to them in the first place.

If Lee Daniels had made similar choices in directing 2009’s Precious: Based on the Novel “Push” by Sapphire, I might not have carried as many qualms about The Butler into the multiplex with me. I was one with the critics who believed that earlier movie to be yet another grim variation on Dem Black Pathology Blues that mainstream audiences have too often and for too long accepted as definitive, comprehensive proof of African American dysfunction. Daniels’s baroque curlicues and smudges (e.g. that Fellini-esque parody popping up on Precious’s TV set) didn’t mitigate the bleakness so much as help mark the whole enterprise as an overwrought extravagance, coated with sociological grease from somebody else’s skillet. I was even less inclined to give Daniels slack a year ago when he’d turned Pete Dexter’s best novel, The Paperboy, into another, even more sodden indulgence.

So I didn’t expect Lee Daniels’ The Butler (What is the huge hairy deal with this guy and titles?) to be a cool, dry model of artistic decorum and to that extent, it matched anticipation. This is one of those movies that starts off moist and stays that way throughout. Even the colors on the screen bleed into another the way they did in The Paperboy as if the whole movie were pre-soaked with salty tears. It’s an unwieldy farrago of elbow-nudging history lessons, domestic (in every sense of the word) tension, bell-ringing uplift, senseless violence and besieged nonviolence. (Question for further study: Which made you cringe more? The out-of-nowhere shooting death in the cotton field or the ascending levels of abuse visited upon the SNCC lunch-counter brigade?)

Still…while I might have wanted something far subtler, less overbearing than what Daniels has put forth here, I found myself giving in to The Butler’s old-school Hollywood storytelling. This is the kind of period melodrama where the periods pile into each other heedlessly and impulsively. Denying the primal power of the movie’s cluttered dioramas is pretending I wasn’t enraptured by any number of Warner Bros. or MGM biopics on the afternoon black-and-white TV sets of my childhood. The historian in me was all too aware of how Daniels’ movie conflated and in some cases blithely ignored the actual chronology of the events sweeping by Cecil Gaines (Forest Whitaker) and his family. But I believe The Butler’s main order of business is to convey emotional, rather than accurate, history. And it manages to do so without any lurid, excessive flourishes – that is, unless you count the flaccid caricatures of the First Families, which though not quite the alleged Saturday Night Live routines, aren’t terribly resonant either, save for Jane Fonda’s brief-but-effective depiction of Nancy Reagan as a brittle empress packing concealed paradoxes.

But do I mind commercial movies whose black characters are more fleshed-out and central to both theme and action than the white ones (as opposed to the reverse)? I’ll let you ponder that as I finally get around to talking about Oprah Winfrey’s surprisingly saucy and limber performance as Gloria Gaines, Cecil’s wife. As with Spencer’s Wanda, Winfrey’s Gloria appears poised to have a neon sign blinking, “long-suffering”, with her every on-camera appearance. But she turns out to be far too nuanced and complex to neatly embody such a cliché. She drinks too much, cheats on Cecil with Terrence Howard’s trifling next-door neighbor (who at least looks as if he earns a paycheck, too) and harbors deep-rooted, but inchoate resentments that not even Cecil’s devotion and achievement can dispel. Nevertheless, the narrative envelops sufficient time for the mercurial Gloria to grow out of, if not entirely overcome, her flashes of bitterness. Neither absolute paragons nor soapy contrivances, Cecil and Gloria seem more lifelike than the melodrama that surrounds them.

I hear some claim that such characterizations are only possible with an African American director or writer. I remain unconvinced, mostly because of the lingering memory of 1964’s Nothing But a Man, which, though directed by a white man (Michael Roemer) who co-wrote it with another (Robert M. Young), set a high standard for realistic, humane depiction of African Americans in love and trouble. And I’m a little bugged that Cecil’s resentful activist son Louis (David Oyewolo) does come across as something of a cliché; at least to those who may have forgotten that there were reasons why nonviolent activists like Louis got tired of turning the other cheek. And why oh why does the movie decide to transform Louis’s gentle, soft-spoken Movement girlfriend Carol (Yaya Alafia) into the sullen, Afro-headed demon of both white and black middle-class imaginings? “Low class bitch”? Really? That’s our takeaway from this beautiful young woman who had earlier strained so painfully hard to keep her resolve during the sit-ins? That’s a vulgarization I can’t easily forgive, no matter how many ambivalent feelings I may now have towards the Black Panthers and their fellow travelers.

Nevertheless, I’m glad to see The Butler get over for one reason above all others: For once, a Hollywood movie about black civil rights doesn’t have a white surrogate hero for whom African-American struggle exerts some manner of soulful transformation. Its box-office success (so far) has tempted pundits to believe that black American cinema may have at last achieved its crossover moment. Excuse me if I don’t join the choir on this one, because I’ve heard this tune many times before now. Maybe what can best be said about this summer of Fruitvale Station and The Butler was uttered fifty years ago this week in a speech better remembered for other phrases: It’s not an end. But a beginning.