Can anybody make a serious, imaginative movie about slavery without being either ignored or picked at? Quentin Tarantino spent almost as much time shaking off flak for his flamboyant genre goof Django Unchained as he did taking bows and counting money. When Jonathan Demme made Toni Morrison’s Beloved into a far-better-in-hindsight movie in 1998, not even the Great and Powerful Oprah’s approbation of, and involvement in its production could make black people assemble en masse to see it when it was released. (Or anybody else. The cost was about $58 million; the movie made about $23 million, at best.)

At least, nobody’s ignoring 12 Years a Slave. It’s at or near the top of just about everybody’s year-end list of best movies. As of the second week of December, it’s made more than $35 million in American ticket sales with more expected around the bend in advance of Oscar season. Still, the movie has attracted its own high-visibility flak from such critics as Armond White, who believes Steve McQueen’s often-graphically violent rendering of Solomon Northrup’s testament as “torture porn” and “less a drama than an inhumane analysis.” David Edelstein, though he believed the movie “smashingly effective as melodrama,” is less fond of McQueen’s “cold, stark, deterministic” approach to the material.

For the record, I admired 12 Years a Slave far more than I loved it. An American/Hollywood director, no matter how smart or savvy, wouldn’t have trusted as much visually as McQueen does here. (In case you didn’t know, he’s black and British.) He isn’t afraid of stillness, of the tension and energy that reside in the act of waiting, as in the first frame, which in just showing the barely contained anxiety in the faces of slaves, gets the movie moving. That said, I doubt very much I will want to see it again. Do I need to watch, once again, a thin young woman getting whiskey tumblers thrown at her head and then having her back stripped of her ebony skin the way you strip a tree of its bark? I do not – and part of me wonders who would, or who needs to.

Still, because the movie is directed by a black man and is written by another (novelist John Ridley), 12 Years a Slave doesn’t get the same mauling Steven Spielberg’s Amistad (1997) received in some precincts for making ciphers of its mutinous African slaves and using their rebellion as a vehicle for white nobility. And I doubt very much the contrarian attacks on McQueen and his film will keep it from winning more awards; any more than Django’s critics kept Tarantino from collecting a screenwriting Oscar.

But no amount of gold statuettes will stop the haters from jumping on the next filmmaker who wants to take yet another hard, idiosyncratic shot at America’s Original Sin. The only solution: Take more shots, make more movies, go as odd, off-base, strange, funny, stern, cold, hot or heavy as the market can bear – and then, if you’ve got the gall, go further than that. There’s no dearth of material to draw upon, from the still largely undiscovered country of slave narratives to contemporary fiction by African American writers who are claiming autonomy over their ancestral experience through daringly imaginative means.

You like lists. Here are places to go for such material:

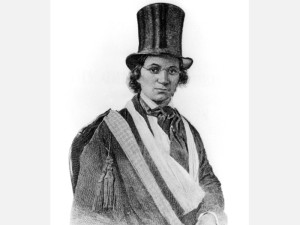

William and Ellen Craft – True story: They were married in bondage in 1846 and escaped two years later from Georgia to Philadelphia in disguise; she (above) as an invalid white man and he as “his” valet. It would take someone with an equally attuned ear for both injustice and comedy, but it could be done.

The Good Lord Bird – Being this year’s surprise National Book Award winner, James McBride’s picaresque comic saga of a young slave boy mistaken as a girl by abolitionist John Brown has likely attracted a few cautious glances from Hollywood. Sophisticated historical satires aren’t exactly meat-and-potatoes fare for multiplexes, no matter who’s involved. But it would be funny, again, if the right tone is struck.

Flight to Canada — An Ishmael Reed seriocomic pastiche that’s never received the credit it deserves for initiating a wave of black novelists claiming imaginative autonomy over their ancestral past in daring, often incendiary fashion. I can’t begin to imagine who would make a movie out of it or what kind of movie it would be. But whenever or however it’s done, it’ll be different from anything that came before.

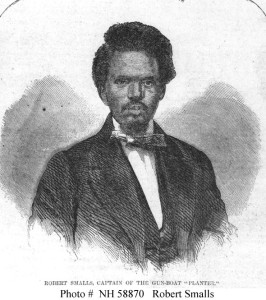

Robert Smalls Steals a Rebel Ship– Another true story; this one about a slave (above) who in 1862 commandeered a cotton freighter with a crew of 17 fellow escapees and managed to hide his identity from Confederate checkpoints, even Fort Sumter, towards the open sea until he was able to raise a white flag to Union blockaders. That alone would be a good movie, though it was just the beginning for Smalls, who later became one of the few African Americans to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives during Reconstruction. (Speaking of which, don’t you think that by now, some great movie about black folk during Reconstruction could be made to counter that damned Birth of a Nation? Just add it to the wish list.)

The Known World – Edward P. Jones’ award-winning novel about blacks owning black slaves already made readers’ heads spin off their necks. A movie version could magnify the shock-and-awe and I’m being REALLY optimistic when I say it could be done. But I’m betting it wouldn’t cause nearly as much trouble as…

The Confessions of Nat Turner – And, yes, I mean William Styron’s version, which has been cherished and despised in near-equal measure by black and white readers alike. America wasn’t ready for Turner in the 1830s and they still aren’t ready for him in whatever form he’s presented or imagined. Which doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be attempted.

Middle Passage and Oxherding Tale — A pair of thinking-person’s ripsnorters by Charles Johnson; the former, as with 12 Years a Slave, puts a freed slave in harm’s way as he finds himself aboard a raucous slave ship heading back to Africa to pick up more “chattel.” The latter chronicles the adventures of a half-white-half-black slave negotiating his way through both worlds with philosophic insight and canny resourcefulness.

Kindred — Let me quote from an Amazon review of the late Octavia Butler’s breakthrough SF novel: “Dana, a black woman living in Los Angeles in 1976, is inexplicably transported to 1815 to save the life of a small, red-haired boy on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. It turns out this small boy, Rufus, is one of her white slave owning ancestors, who she knows very little about. Dana continues to be called into the past to save Rufus, and frequently stays long periods of time in the slave owning South. The only way she can get back to 1976 is to be in a life threatening situation.” How is this NOT a movie waiting to happen? Why hasn’t it happened by now?

And on and on and…