Entries from December 2016 ↓

December 30th, 2016 — jazz reviews, movie reviews, on writing lit -- and unlit, TV reviews

Yes, I know. This happened within the last few days, followed closely by this and then, for God’s sake, this. I still say 2016 isn’t, as so many insist, The Worst Year Ever for high-profile deaths; not in my lifetime anyway.

I checked. Consider 1959, whose carnage all but commenced February 3 with Buddy Holly, Richie Valens and J.P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson crushed and shredded by an Iowa plane crash. There followed the deaths, in no particular order, of Billie Holiday, Errol Flynn, Raymond Chandler, George Reeves, Mario Lanza, Frank Lloyd Wright, Lester Young, George C. Marshall, Carl “Alfafa” Switzer, Victor McLaglan, John Foster Dulles, Cecil B. DeMille, Bert Bell, Kay Kendall, Preston Sturges, Eddie “Guitar Slim” Jones, Ethel Barrymore, Boris Vian, Sidney Bechet, Lou Costello…

Some of these deaths were untimely and unexpected, others weren’t. And go sit in a corner if you even think of responding with something like, “Yeah, but these were all OLD people…”

I can easily pull other, similar examples out of my memory bank, especially Bobby Kennedy’s “very mean year” of 1961 (Ernest Hemingway, Patrice Lumumba, Gary Cooper, Booker Little, Barry Fitzgerald, Dag Hammarskjold, Sam Rayburn, Scott LaFaro, Ty Cobb, James Thurber, Maya Deren, Dashiell Hammett, Grandma Moses, Chico Marx, Jeff Chandler, George S. Kaufman, Carl Jung…) spilling right into the following year (Marilyn Monroe, William Faulkner, Ernie Kovacs, Eleanor Roosevelt, Benny Paret, Niels Bohr, Isak Dinesen, Myron McCormick, Charles Laughton, Franz Kline, C. Wright Mills…) and onwards towards 1966 (Lenny Bruce, Walt Disney, Evelyn Waugh, Bud Powell, Montgomery Clift, Frank O’Hara, Bobby Fuller, Richard Fariña…) and 1974 (Duke Ellington, Earl Warren, Jack Benny, Agnes Moorehead, Ivory Joe Hunter, Frank McGee, Cornelius Ryan, Darius Milhaud, Chet Huntley, Bobby Bloom, Frank Sutton, Cass Elliot, Joe Flynn, Charles Lindbergh, Nick Drake, Richard Long, Cyril Connolly, Gene Ammons, Otto Kruger, Jacqueline Susann, Amy Vanderbilt…)

And I could go on like this forever. Do you know why? BECAUSE SO DOES DEATH, PEOPLE. Once you stop thinking of your own era as being, like, so totally unique, it helps make everything around you less frightening.

Repeat after me and say it over and over at night to help you sleep: Years don’t make us better or worse. WE make years better or worse.

With that in mind, I’d like to submit my own random, totally subjective list of the things that made 2016 not suck quite as much as you might otherwise believe. For one thing, it was, despite the prevailing socio-political landscape, a terrific year for African American culture, as many of the attached items will attest. And that will be as true of 2016 ten years from now as it is now, no matter what state the United States will be in by then:

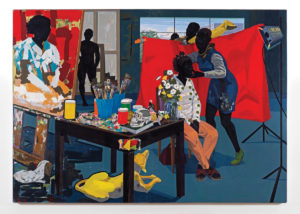

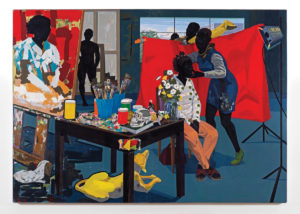

Kerry James Marshall – Along with Wrigley Field, the Billy Goat Tavern and the architectural river cruise, the best part of my late summer trip to Chicago was “Mastry,” a comprehensive exhibition of Marshall’s paintings and drawings at the Museum of Contemporary Art whose breadth and intensity of vision almost brought me to my knees. The exhibition later travelled to New York where it likewise riveted, astonished and inspired millions more. There were many who saw hope with the Cubs’ long-deferred triumph in this year’s World Series. I saw hope and much more in this living Chicago institution.

Atlanta – Donald Glover’s masterly FX series about hip-hop life along the edges validated my long-held suspicions that there was something about its eponymous city that transgresses laws – or at least customs – of time and space. It’s a city where Justin Bieber is magically transformed into the bratty young black man you suspect he’s always wanted to be and where every single plan that an ambitious brother like Glover’s Earn can conceive is chopped up and pureed into unrecognizable, perplexing anomalies. Though he was writing about DJ Shadow this past summer, Greil Marcus could have been talking about Earn and his milieu when he described “a sampler of bits and pieces of dislocation in modern life – finding yourself in the wrong place at the wrong time and realizing you were born there – the textures can seem meretricious, accepting, as if there’s really nothing left to argue against…[But] [b]y its end, yes – you don’t know where you are.”

Mahershala Ali – From Ali’s soon-to-conclude duty as Remy Danton, the lovelorn fixer-for-the-highest-bidder on House of Cards, one sensed coiled steel, contained explosiveness and intuitive graces that this actor could call upon for more daunting challenges. Didn’t take long for him to display these qualities when playing the year’s more conflicted criminals. As Juan, the neighborhood crack dealer in Moonlight, Ali lets you see both the smoldering menace with which he quietly asserts proprietorship over his network of mules and the deep, if enigmatic well of sympathy that allows him to connect with a bewildered, vulnerable boy bullied at home and at school for reasons he can’t fathom. For the smaller screen, Ali brought gray shadows and complex motivations to his portrayal of Cornell “Cottonmouth” Stokes, Harlem crime kingpin and chief nemesis of the bulletproof hero-for-hire in Marvel-Netflix’s Luke Cage. He’s so persuasive at evoking a bad man convinced of his essential goodness that one felt a slow leak oozing out of the whole series after his departure. His dual triumphs make one yearn for more opportunities for Ali to play anti-heroes who can deal with the devil while doing God’s work.

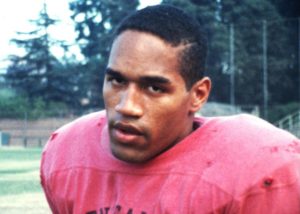

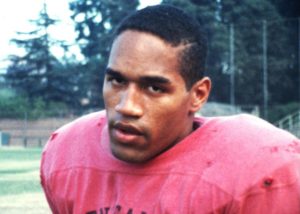

O.J.: Made in America & The People Vs. O.J. Simpson – It doesn’t matter whether you preferred Ezra Edelman’s epochal, illuminating five-part documentary series for ESPN or the Scott Alexander-Larry Karaszewski dramatization which made heroes of erstwhile laughing stocks Marcia Clark (Sarah Paulsen) and Christopher Darden (Sterling K. Brown) without in any way mitigating the scorched-earth genius of Johnnie Cochran (Courtney B. Vance); all of which actors, by the way, won much-deserved Emmys. What both these vastly different approaches to a reverberating crime have in common is what they imply about the glaring inadequacies of day-to-day news coverage. You could argue that all the nuances, subtleties and socio-historical contexts available now to screenwriters and documentarians weren’t as easily accessible to journalists as when the actual Simpson trial was unfolding 22 years ago. But as the last election cycle proved, the 24-hour news cycle, whether on cable or through the Internet, barely bothers even to try thinking such things through. All we’re left with, then and now, are the usual bromides e.g.: It’ll be years before we know what really happened; There’s always more to the story; There’s more here than meets the eye…Blah…Blah…Blah…Whimper.

The Sport of Kings – From the great, relatively forgotten, but still very much alive (at this writing) African American novelist William Melvin Kelley, I recently found out that the word “race” derives from the medieval Italian “razzo,” meaning “any given breed of horse.” I’m betting that C.E. Morgan, a intelligent, imaginative and startlingly perceptive daughter of the Bluegrass State, was aware of this arcane connection when she wrote this novel about a Kentucky horse breeder whose attitudes about race roughly parallel those of the odious John C. Calhoun. He has his reasons, of course, and Morgan’s too conscientious a novelist not to take their full measure, however petty they are and however grievous their impact on others’ lives. His venom afflicts two of those lives. One belongs to his spirited, magnetic daughter who shares his obsession with creating the next Secretariat; the other belongs to a black ex-convict from the mean streets of Cincinnati hired to help train this super horse. I’ve pressed and imposed this novel upon others and yet I’ve been struggling to figure out why. One possible answer just now came to me through David Ulin’s retrospective essay about Double Indemnity for the Library of America’s “Moviegoer” site when he cites a quote from the movie’s coscripter Raymond Chandler: “It doesn’t matter a damn what the novel is about…The only writers left who have anything to say are those who write about practically nothing and monkey around with odd ways of doing it.” Self-serving, I suppose, since Chandler’s reputation while alive was that of an innovative genre writer. Morgan’s novel, aiming for higher ground, isn’t about “practically nothing,” but about many things at once. Yet as with great writers of American noir such as Chandler, Sport of Kings surges and leaps heedlessly into big emotions and grand melodrama, which Chandler believed “was the only kind of writing that I saw was relatively honest.” Ulin pushes these points further by defining them as “conventions of the hyper-real.” I haven’t the time or the space here to get into the specifics, but if you can imagine what base-level 20th century American melodrama, whether practiced by realists or “hyper-realists,” can bring to 21st century issues of race and class, then you will understand why I’ve been bullish on this particular horse opera. I didn’t read Sport of Kings so much as submit to its power and it’s been too long since any new novel did that to me. (I was one of the judges who singled Sport out for the Kirkus Book Prize for fiction. If you can call it up, our citation is quoted here.)

The Arab of the Future, Vol. 2 – Along with Art Spiegelman, Roz Chast, Marjane Satrapi, Joe Sacco and the late Harvey Pekar, cartoonist Riad Sattouf has helped establish the graphic memoir as the most innovative and affecting narrative art form to have emerged in the late 20th century. Given the relentlessly bleak news coming out of Syria in recent years, Sattouf, who once was a regular contributor to Charlie Hedbo, may be providing the most timely and poignant contribution with his autobiographical account of growing up between different cultures. In the first volume, avid, adorably fluffy-haired Riad is shuttled back and forth between France, where his mother Clementine is from, and the volatile Middle East of the 1980s where his Syrian father Abdel-Razek embraces the then-burgeoning Pan-Arab movement. In this second volume, covering 1984 and 1985, Riad’s family settle in his father’s hometown of Ter Maaleh as the country reinvents itself under the dictatorship of Hafez Al-Assad. The little boy must adjust to a new school with its fundamentalist dictates, corporal punishment and the usual highs and lows of socializing with other children, complete with bullying of an especially brutal and bigoted kind. In recounting these and other vicissitudes, Sattouf maintains his wit, balance and equanimity towards all his characters, even at their worst. This is especially true of his father, who is by turns insecure, pompous, clueless and frantic to fit into whatever future his homeland devises for himself and his family. As with its predecessor, the second volume of Arab of the Future makes you wonder how long it’ll be before Abdel-Razek’s dreams come crashing down. But even with that dire prospect, the warmth and wisdom seasoning his son’s rueful memories keep you hoping for the best for the Sattoufs while bracing for the worst.

Weiner — It’s odd how some things can both become dated and gain added significance in only a few months. When I first saw Weiner in the theater, it was early summer, Huma Abedin’s mentor was still well-positioned to be the next president and I came away from the documentary thinking mostly about Abedin’s inscrutably slow-burning gazes at the movie’s main subject who, for all his energy and earnest impulses to do good, came across here as he did everywhere else in the last four years: As an incurable narcissist, stabbing himself, scorpion-like, with his own…um…wretched excesses. I saw the film again on Netflix a couple weeks ago and somehow all that tattle-and-buzz about a man, his penis and social media don’t seem all that important when compared with the brazen lies and mendacity we’ve already seen in play so far from the incoming administration. This time around, what was far more important to me were all those brown and black people occupying the periphery of the action who kept shouting at the TV cameras and their enablers to stop yammering about the man’s dickishness and concentrate on what needs to happen in their neighborhoods to make them better. Wouldn’t it be something if this documentary ended up signifying both the peak and decline of the Age of Gossip and Innuendo? As. If.

Lemonade & Daughters of the Dust – It now seems like forever and a day since Beyoncé dropped her “Formation” video into Super Bowl Week festivities the same way you imagine a visitor from the future, unrecognizable to present-day eyeballs, dropping in on the Iowa Caucus. The 24-hour news cycle chewed its immediate impact to tiny bits until there was little left to the astonishment but empty bluster and gaping bemusement. My own reaction was something akin to: Damn. It almost looks as if Julie Dash directed this badboy! Those of us who cherish Dash’s Daughters of the Dust, her gorgeous 1991 cinematic tone poem set in the turn-of-the-20th-century Georgia Sea Islands have spent the intervening years keeping track of her movements and looking for signs that the movie wasn’t forgotten. And while Dash didn’t direct the “Formation” video, or any of the others emerging from Bey’s daring, insurgent album, Lemonade, there were enough resonances from Daughters to summon a movement to get an enhanced edition of the film out and about to art houses throughout the country. Because Daughters occasioned the first four-star review I ever gave as a Newsday movie critic, this convergence of cultural forces was the happiest I can remember.

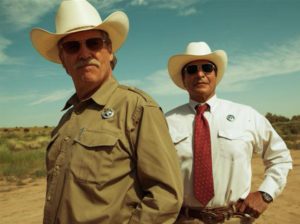

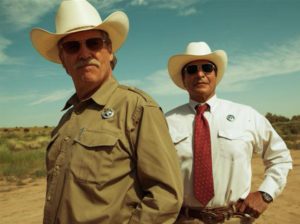

Hell or High Water – As I’ve babbled to several people till I bored my own self, I wasn’t at all bullish on movies this year. (The worst of the summer blockbusters, in my opinion, gets its definitive raking-over here by the ever-engaging critical thinkers over at HISHE, who once again outclass what they’re critiquing.) I suppose I’m an incurable aficionado of the mid-to-late-1970s wave of gritty American cinema. And while I think this badlands chase thriller from David Mackenzie wouldn’t necessarily stand out among the glorious products of 40-something years ago, it offered elemental pleasures similar to those movies’: a taut-wire storyline that wastes no time; dry, cool dialogue that likewise goes about its business in real time and no-sweat laconic performances that play changes like a cool jazz combo. Coolest and driest of all is Jeff Bridges in his best performance in years as a Texas Ranger in pursuit of bank robbers aggrieved by the economic unpleasantness of recent years. I also quite liked Chris Pine as one of the robbers, though unlike some reviewers I don’t think he quite steals the movie from Bridges so much as shares the win in the end. If you’ve seen it already, you know there’s added implication in that previous sentence. If not, what the hell are you waiting for?

The Liberation Music Orchestra Redux – It all keeps coming back to Chicago at whose jazz festival this year I saw Carla Bley leading the revived Liberation Music Orchestra founded almost a half-century ago by the late Charlie Haden. He’d spearheaded a restoration of the 12-piece band a few years back, but his failing health prevented him from pressing ahead. Bley, who’d been with the orchestra at its creation as both pianist and arranger, picked up the ball and carried on Haden’s dream of focusing the orchestra’s progressive agenda on ecological issues. The Chicago set included pieces from the album Time/Life (Impulse!) whose playlist includes Bley’s multi-textured tribute to Rachel Carson, “Silent Spring,” and Haden’s own “Song for the Whales.” The timing of their return is all-too auspicious and I have a sinking feeling that global warming may soon end up being among many things they’ll be compelled to make music about.

December 3rd, 2016 — jazz reviews

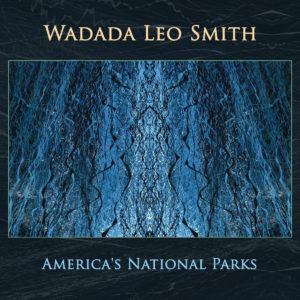

It strikes me – as it should strike you – that there’s an especially pervasive aura of American-ness suffusing this year’s roundup, especially given that the words, “America” and “American” appear in most of the titles. This motif was making itself apparent as I started putting the list together before November 8 and it became even more – what? “prevalent”? “0mnipresent”? “prescient”? – after November 9.

One need not use this space for further dissection of what happened, and didn’t, in that 24-hour period. It’s all we keep talking about, and avoiding talking about, sometimes simultaneously. All I can say for my part is that these selections reflect a socio-cultural patriotism in both my conscious and subconscious mind that, in spite of all that has happened and may soon happen, remains steadfast. Whatever’s coming down will likely give jazz even more of a beating than it’s already sustained through this (so far) dismaying century. But the best thing one can say is that it’s no more beaten up or beaten down than it’s been since, let’s say…1968? That was a helluva year, too. Some of us feared the worst after that election. . But we made it. And so, somehow, did music.

That’s all I got. You want to feel warmer and fuzzier about things watch a Wal-Mart commercial. But if you really want to feel good about this country and its (say it with me, America) Greatest Art Form, these eclectic items, I promise, will do the job.

In the deathless words of Yuri Gagarin (who wasn’t American, but we’ve always secretly wished he had been), “Let’s go!”

1.) Jane Ira Bloom, Early Americans (Outline) – Hard to believe that after sixteen albums through nearly four decades, Bloom has never before walked the high wire with nothing more than a bass (Mark Helias) and trap set (Bobby Previte). She comes through just as you’d expect: with bold, deep tones that swallow you whole and bright,supple phrases that recombine themselves into breathtaking shapes. From Helias and Previte, she gets the kind of backup an ace improviser deserves. They merge their rhythmic instincts with her soprano saxophone’s probing, soaring voice to become one entity, totally in control of whatever they take on, regardless of tempo or mood. On the (literally) groovy “Singing the Triangle,” they seem to take turns at the wheel with Previte’s toms assuming melodic duties with his characteristic wit and bravado. When it’s just Bloom and Helias, as on “Other Eyes,” the colloquy is so detailed and urgent that you think you’re eavesdropping on a secret plan for curing cancer, hunger and ignorance. And when it’s just her, in full flight, she asserts her command of every aspect of her art whether assembling a necklace of diamond-hard chords and taking them apart (“Rhyme or Rhythm”), burrowing deep into the contours of a classic melody (“Somewhere’) or blowing the blues with joyous abandon (“Big Bill”). It’s now official and can be certified by any number of witnesses: There’s no one like her. Anywhere.

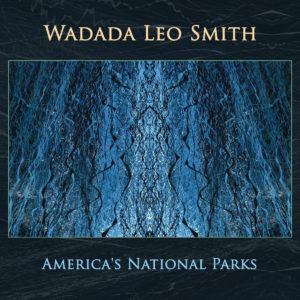

2.) Wadada Leo Smith, America’s National Parks (Cuneiform) – Having previously contained multitudes in his matchless pageant of historic landmarks (2012’s Six Freedom Summers) and his widescreen embrace of Midwest natural wonders (2014’s The Great Lakes Suite) Smith, himself a force of nature whose renown has burst into a big, blinding glow at age 76, would of course be inclined to celebrate this year’s National Park Service centennial with a similarly ambitious and dauntingly variegated tour through the service’s assets, both widely known (“Yosemite: The Glaciers, the Falls, the Wells and the Valley of Goodwill 1890”) and relatively obscure (“New Orleans: The National Culture Park USA 1718”). Don’t expect either a Copland-esque procession of soaring, meaty strings or a rustic stream of acoustic guitar riffs cueing your awe over big rivers, big mountains and bigger skies. Smith has a way of swelling the American heart that’s distinctly his own; his horn, by turns plaintive, coarse and slashing as Miles Davis’ once was, assumes an even heavier, more rugged tone to keep up with his voracious impulse to take in the colors, textures and elements of his subject’s landscapes, even when he’s mostly imagining what they’re like. (“You don’t need to visit a park,” he says in the liner notes, “to write about a park.” And there’s something about his submission to the imaginative muse that overpowers your literalist’s skepticism.) His instrumental voice fuses effectively with that of cellist Ashley Walker and the rest of his Golden Quintet, with pianist Anthony Davis, bassist John Lindberg and, most especially, drummer Pheeroan akLaff, seems to take on added strength and power from the music’s robust challenges. It’s not an easy hike. But if you give in to the arcane beauties and shape-shifting aspirations of Smith’s muse, you’ll remember most, if not all, of what your inner ear sees.

3.) Fred Hersch Trio, Sunday Night at the Vanguard (Palmetto) – We’ve been here before with this group and we know from previous experience that they come to kill every time they show up downstairs on 178 Seventh Avenue South in Manhattan. So what’s different this time? Maybe because, as the title says, it’s Sunday night and as every Village Vanguard habitué knows, Sundays are when performers wind up their six-night engagements. While critics always show up Tuesdays for the opening-night sets, the Sunday closers can be less-heralded occasions when the ensembles, after a hard week’s work, are at once locked in tight and empowered to let loose. Hersch tweaks expectations from the jump with an appropriately spry-and-whimsical treatment of “A Cockeyed Optimist,” a Rodgers-and-Hammerstein chestnut that isn’t often put through the jazz colander. The spiraling variations Hersch’s piano applies to the melody makes you wonder why this is so and then you realize, once again, that it’s because Hersch may be one of the few pianists of his generation with the open-hearted imagination to re-invigorate mid-20th-century Broadway grandeur for post-Millennial jazz heads. Along with bassist John Hébert and drummer Eric McPherson, Hersch builds upon this frisky beginning with a couple of classics from the jazz repertoire (“We See,” “The Peacocks”); some of his own compositions (“The Optimum Thing,” “Calligram,” “Black Wing Palomino”) that deserve to be part of that repertoire and, of all things, a ruminative, fireplace-glow cover of Sir Paul McCartney’s “For No One.” Hersch’s liner notes say he and his partners were “in the zone” on this Sunday night last March. He’d know. All I know is that I had an especially hard time keeping it all out of my player – and my head – for the rest of the year.

4.) Henry Threadgill Ensemble Double Up, Old Locks and Irregular Verbs (PI) – For a change, this year’s Pulitzer Prize winner for music is letting his sax and flute sit this dance out while leading two pianos (Jason Moran, David Virelles), two altos (Roman Filiu, Curtis McDonald), a cello (Christopher Hoffman), a tuba (Jose Davila) and a drummer (Craig Weinreb) in a four-part suite paying tribute to the late Lawrence “Butch” Morris (1947-2013), Threadgill’s fellow Vietnam War vet and partner in avant-garde insurgency and orchestration. The band is a typically eccentric gathering, but it is by no means Threadgill’s strangest combination of instruments. And if the dense musical collages assembled by the composer are as inscrutable and idiosyncratic as ever, they are also less forbidding; the angular dynamics and static-but-surging momentum urgently aligned with the wary-to-yearning-to-anxious mood swings of the present day. Indeed, I think Old Locks and Irregular Verbs is Threadgill’s most emotionally accessible work since Where’s Your Cup?, his 1996 Columbia album with Very Very Circus. And it couldn’t have come at a better time for him – and for our jittery selves needing the reassuring possibility of discovery and adventure in an uncertain future.

5.) Allen Toussaint, American Tunes (Nonesuch) –It may not quite fit into whatever gets categorized as “jazz” in its ever-marginalized marketing niche; not as neatly as 2009’s incandescent, expansive Bright Mississippi where Toussaint got to wander through a smoke-filled, twilit museum of 20th century black music with the likes of Don Byron, Nicholas Payton, Brad Mehldau, Joshua Redman and Marc Ribot. But even with a relatively smaller guest list of notables (Charles Lloyd, Bill Frisell, Rhiannon Giddens), this album, whose concluding sessions were cut a month before Toussaint died in November, 2015 while on a European concert tour, is a deeply moving valedictory for an epoch-making legacy. No other pianist, living or dead, could apply his ironwork-ornate flourishes and mosaic-tile detail to such chestnuts as “I’m Confessin’,” “Viper’s Drag,” “Rosetta” and “Waltz for Debby.” No one could better evoke the resilient, inexhaustibly vivacious spirit of his home town when rolling through “Mardi Gras in New Orleans,” “Big Chief” and “Hey Little Girl”; just as no one else could have written “Southern Nights,” whose solo rendering here is sweet-and-sour enough to sting the eyes. But you should save your tears for the finale: his vocal performance of Paul Simon’s “American Tune,” which goes down, especially this season, like both commiseration and a blessing, even when you’re stopped dead in your tracks by the plaintive, unadorned manner with which he sings: “Still when I think of the road/we’re travelling on/I wonder what went wrong/I can’t help it, I wonder what’s gone wrong…” And I wonder how we’re managing to go on without him.

6.) Darcy James Argue’s Secret Society, Real Enemies (New Amsterdam) — On the most elemental level, I can (almost) see conservatives’ point when they keep insisting that government isn’t your mother. But government also isn’t, or shouldn’t be, that creepy uncle who insists on hanging around your bedroom, listening in on your phone conversations, reading your mail and letting rich people with giant-squid tax shelters follow you around while you buy things. This is the world we’ve been living with for most of this – as I referred to it earlier – dismaying century so far; full of night sweats in broad daylight, cynical whistling-in-the-dark and equivocal behavior by those who’ve known too much for too long. So why, you wonder, would you want to listen to a whole damn album summoning up this dark matter? Because Darcy James Argue is a wicked-smart conjurer of phantasmagoric narratives grounded in real-life mystery. (See 2014’s Brooklyn Babylon for further enlightenment.) And his 18-piece Secret Society kicks ass and proves itself worthy of its name by enabling its leader to put forth a gnomic, allusive, brassy and insinuating musical soundtrack you can apply to any noir mind-movie your paranoia can summon to life. It’s the kind of story I wish someone of Argue’s boundless energies and bountiful vision didn’t have to tell. But, as many have observed of Edward Snowden’s transgressions, I suppose somebody had to do it.

7.) Joshua Redman & Brad Mehldau, Nearness (Nonesuch) – These two guys have been all but joined at the hip since Mehldau served in Redman’s quartet along with drummer Brian Blade and bassist Christian McBride. (Yes, that actually happened. Only one 1994 album, but, as you’d imagine, it remains a good, if retroactively undervalued one.) Redman and Mehldau have supported and inspired each other in the intervening years to the point where one is tempted to refer to them as the Huck and Tom of their generation of jazz musicians. I hope you’ve noticed that I did not say “Huck and Jim” and if you’ve read the books and been paying attention to their respective career arcs, it wouldn’t be hard to decide which is Huck and which is Tom. Or would it? Never mind. What you need to know about these live duets from five years ago is that they get off to a bit of a ragged start on “Ornithology,” but soon meld together in rapturous communication on Mehldau’s “”Always August.” Here and throughout the rest of the album, you’re aware of how much each of them has grown into their respective styles; Melhdau’s piano unfurling sheets of rich harmonies while Redman, on tenor and soprano, shows how impressively he’s contained and controlled that prodigious talent that got everybody excited more than two decades ago. And he can still level you when he wants to; most especially on a stunning extended solo break he takes on “The Nearness of You,” throughout which he doesn’t seem to take a breath – except, maybe, your own. Mehldau likewise makes your eyes grow big with his own derring-do on “In Walked Bud.” But they’re at their most potent when putting their heads together on Mehldau’s originals, notably the easy-rolling (at first) “Old West.”

8.) Kenny Barron Trio, Book of Intuition (Impulse!/Universal) — Sometimes, maybe most times, you just want music to come across like sunlight shimmering along the nearest available body of water, the undulations so soft and sweet that you don’t care how far or how high you’re floating. At 72 years young, Barron may be the undisputed living grand master of jazz piano. He is, without dispute, his idiom’s t most agile communicator in whatever setting or at whatever tempo. With bassist Kiyoshi Kitigawa and drummer Johnathan Blake, the group he’s been leading in nightclubs and concert halls for most of the past decade, Barron delivers a state-of-the-art smorgasbord of straight-ahead pleasure, much of it braced by the Latin and Brazilian rhythms that highlight his tuneful dynamics. The table is set from the start with “Magic Dance,” whose soft bossa-nova beat is Barron’s happy place; happy enough, in any case, for him to tempt fate with a flurry of arpeggios that settle soon enough into an easy-does-it samba. His homage to Bud Powell, “Bud-Like,” surges into Afro-Cuban overdrive while his fealty to Thelonious Monk is served with two of the Enigmatic One’s lesser-known pieces, “Shuffle Boil” and “Light Blue.” In each of these, Barron doesn’t try to out-Monk Monk so much as let his own graces impose their own manner of wit and mischief into their workings. It’s one of those records (and I have at least one of them every year) that doesn’t reinvent the wheel, but reminds you why and how wheels work so beautifully.

9.) Etienne Charles, San Jose Suite (Culture Shock) – This ambitious work, enacted here in twelve parts, encompasses not just one, but three San Jose settlements in three different Western Hemisphere spots: California, Costa Rica and Trinidad. What’s distinctive about each of these San Joses/St. Josephs is less important to the formidably gifted Charles than what they share and the music he fashions from his inquiries is bright, ingenious and bursting with provocative rhythmic combinations. The polyglot of Indo-African-Latin-American-European influences not only evokes the past but advances a singular new musical language redolent of the “creole soul” that gave trumpeter-composer Charles the title of his potent 2013 album. Whatever you call it, as pure sound, it is gorgeous to behold with intensely committed interaction throughout from Charles, altoist Brian Hogans, guitarist Alex Wintz, pianist Victor Gould, bassist Ben Williams and drummer John Davis. The last three tracks are a mini-suite, “Speed City,” in which Harry Edwards recalls his tumultuous career at San Jose State University when he helped spearhead the African-American boycott/protest of the 1968 Olympics. At first, I thought the “Speed City” trifecta differed so much from the nine previous pieces that they belonged on a different album. Over time, I’ve come to think they not only belong, they’re a bonus to what precedes them; mostly because Charles and the rest of his crew leave blisters no matter when or where they turn up the heat.

10.) Delfeayo Marsalis & The Uptown Jazz Orchestra, Make America Great Again! (Troubadour Jass) – In the most politically astute and (therefore) funniest Saturday Night Live sketch of the late, unlamented campaign season, Darnell Hayes (Kenan Thompson), host of an edition of “Black Jeopardy!” made extra special by the participation of a white blue-collar-Trump-supporting contestant (Tom Hanks), is given the last word: “When we come back, we’ll play the National Anthem and see what the hell happens.” Well, you’re all encouraged to stand – or, if you roll that way, kneel – when this album begins with a stately, serious-as-a-heart-attack rendition of “The Star Spangled Banner.” And what the hell happens after that’s over is a raucous compound of house party, choral recital and vaudeville revue offering, as one song lyric puts it, “soul food for your ear.” The album’s title track is played for cheeky irony with the trombone-playing Marsalis brother’s narration intoned by actor Wendell Pierce with hambone slyness over an antic riff reminiscent of Mingus’ “Fables of Faubus.” The words question whether the “catchy slogan” is a “pragmatic proposition” to “a melting pot of diversity fighting a juggernaut of adversity.” Did Marsalis and company know how things would turn out after the recorded this session? Feel free to ponder that as his 19-member orchestra throws down a potpourri of hard-driving arrangements whose sources range from the Dirty Dozen Brass Band (“Snowball”) to Benny Carter (“Symphony in Riffs”). Final question: Is this a bittersweet send-off to the optimism that followed the election of 2008 or a defiant hello to the dark-edged uncertainties unleashed by the election of 2016? Guess we’ll know for sure in eight years, if not sooner.

‘

HONORABLE MENTION: Sonny Rollins, Holding the Stage (Doxy/Okeh); Jonathan Finlayson & Sicilian Defense, Moving Still (PI); Matt Wilson’s Big Happy Family, Beginning of a Memory (Palmetto); Bill Frisell, When You Wish Upon A Star (Okeh); Roberta Piket, One for Marian (Thirteenth Note); Chris Potter, Dave Holland, Lionel Loueke, Eric Harland, Aziza (Dare2); Anat Fort & Gianluigi Trevisi, Birdwatching (ECM).

BEST VOCAL ALBUM: Catherine Russell, Harlem On My Mind (Jazz Village)

BEST REISSUE/HISTORIC ALBUMS: 1.) Larry Young in Paris: The Ortf Recordings (Resonance); 2.) Joe Bushkin Quartet, Live at the Embers 1952 (Dot Time) 3.) Joe Lovano Quartet, Classic! Live at Newport (Blue Note)

BEST LATIN JAZZ ALBUM: Etienne Charles, San Jose Suite. HONORABLE MENTION: Sao Paulo Underground, Cantos Invisieves (Cuneiform)