October 8th, 2022 — family history

I never wanted it in the first place. As I’ve told people over six decades, from Grade 4 on, I wanted almost anything but a flute. A trumpet was my first choice for elementary school music education. With Miles Davis lulling me to sleep practically every night from toddler-hood and other pieces of my living-room soundtrack ranging from Chet Baker and Clifford Brown to Gerald Wilson and Art Farmer, what else could I want but a trumpet?

No dice.

“We. Can’t. Afford. A. Trumpet,” my father said, staring deep into my eyes and enunciating every word as if it were one of those times I’d done something irreparably bad to the sofa or the bathroom sink. “If. You. Want. To. Play. An. Instrument. We. Can. Only. Afford. A. Flute. Now. Are. You. SURE. You. Want. An. Instrument? Are…You…SURE…You…Want…A…Flute?”

Well…No…Dad…I had my heart set on a trumpet. (And Jesus, does that speech stretch longer in one’s memory or what?) Any brass instrument would have been A-OK with me. When, not many years later, my younger brother was given the chance to try the trombone, I picked it up out of curiosity and found, to my surprise, that I could actually get a note out of it on my first try.

As for the flute…let’s just say that I was a slow learner when it came to things like metal mouth-pieces and where exactly to align the mouthpiece beneath my lower lip. “It’s just like blowing into an empty Coke bottle,” others would insist, and I had to take their word for it because I didn’t think empty Coke bottles were useful for anything besides the nickels you could get in those days for their return.

Thus began a near-lifelong grind, a lengthy arranged marriage with scattered intervals of mutual understanding and, once in a great while, unexpected joy. The flute and I decided that if we were stuck with each other, we’d try to make the best of it. Understating matters, I was not the most devoted partner in this transaction, especially in the beginning. I understood perfectly that practice was the gateway to musical proficiency, and I tried. But I simply could not meld my being with this long silver tube, this slender, imperious enigma with padded keys. It never beckoned me to do great things.

Also – and this is unfair, mortifying and fucked up in at least a half-dozen ways (consider this a trigger warning), there was in those ancient early-1960s a consensus stigma attached to young male flautists since most flute players in junior high and high school orchestras were female. (“Whassamatter, Eugene?” one fifth grade wit asked me. “They run out of clarinets?”) My awkwardness in all things athletic and most things social already marked me as, putting things as baldly as my contemporaries did, A Pussy! I internalized this ugliness for much of my early years carrying a flute around and it added to the brick wall of self-consciousness that I lugged around with me along with my flute and briefcase. (Why, yes, I did! Talk about asking to get beat up!)

And in case you think the times we live in are more evolved: sometime near the start of this new century I was casually conversing on the phone with a friend of mine who told me one of her school-age daughters was taking up the flute. My subsequent “Hey, so did I!” aroused a deep sigh at the other end of the phone and eventually the following query: “Were your parents trying to make you gay?” Understand that she was merely commenting, drolly, as ever, on the presumptions and superstitions of a more savage time and place. So I wasn’t offended. I’m betting today there’d be many more who are.

Still, the flute did enable me to read music. It never gave me total facility and absolute confidence in fusing sound with notation, but at least I knew where everything was supposed to be when I practiced sufficiently. And after the flute (by then, the Boosey & Hawkes model you see pictured above) followed me to high school and got me into the marching band and orchestra, I made still another discovery: I could actually seek and find notes with my ears and even string together familiar melodies from scratch. I could poke my way through the first chorus of “The Swingin’ Shepherd” and even the occasional pop hit, especially “(Sittin on) The Dock of the Bay.” No one would then, or ever, mistake me for Hubert Laws or Herbie Mann, but it was nice to know that I had at least a modicum of ability, even if there was no teacher at the school in those days who could help me take my jazz leanings to the next level.

Somewhere in my junior year of 1968-69, I stumbled into what was likely my peak as an instrumentalist: a chance to play flute interludes for The Open Stage, a Hartford-based theater company that was putting on “A Hand is On the Gate,” Roscoe Lee Browne’s staged renderings of African American poetry. There were other, better young musicians my age recruited for a backstage combo and to this day I find it somewhat miraculous that I was able to hold my own with them. One of them even asked me to help her out with an audition tape. Was it possible that, after years of approach-avoidance games with each other, the flute and I were discovering, if not passion, something close to respect for one another? A spark to be kindled into, at the very least, a productive, long-term alliance of sorts?

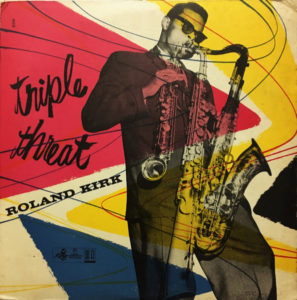

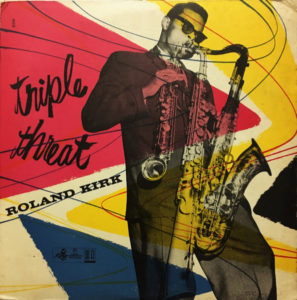

Again, no dice. And the person who finally got between us was Eric Dolphy, the nonpareil reed magician whose music I’d only casually encountered at other people’s houses. Not my father’s brand of whiskey, saying the least. He’d seen Dolphy live a couple years before the latter’s death in 1964. It was at a Newport Jazz Festival and Dolphy was honking back at seagulls in mid-solo with his saxophone. Dad thus determined him to be weirder than Roland Kirk, which is to say, too weird for further study. I came to love both of them without reservation, especially Dolphy. “Left Alone,” “Sketch of Melba,” along with the flute solos Dolphy took with Charles Mingus, Oliver Nelson, Chico Hamilton and his own bands were enough to convince me that he was the undisputed heavyweight champion of the flute. Any presumptions I ever had of even approaching Dolphy’s magnitude, much less tooling along securely in a slower lane were deflated. It didn’t help that as far as my fellow jazz aficionados were concerned, the flute placed at least third among the instruments conferring immortality upon Dolphy, probably even fourth. Thomas Chapin, another reed master and Rahsaan Roland Kirk devotee who, as with Dolphy, died too soon, also played a killer flute. But also as with Dolphy, it wasn’t the only instrument he played. It wasn’t just that I could no longer imagine myself playing the flute as well as these and other greats. It was that I couldn’t imagine giving as much dedication to playing the instrument as it required – and deserved.

And besides, given that I’d by age 15 fully committed myself to writing, I would find then and in years to come a new outlet for my natural inclination for fusing sound and meaning. I frequently wonder whether I would have discovered that impulse on my own without a flute or any musical instrument at all. I’m sure the flute helped; a significant factor mitigating my earliest reservations, even my grievances over not getting that trumpet I’d wanted at the outset. All I know is that I began to feel more like a musician when I wrote than when I was merely Playing Music.

So I let things go with the flute, even as the aforementioned Boosey & Hawkes followed me in subsequent years from Hartford to three other cities and at least five other homes. After my most recent move back to Philadelphia last June, I took the old thing out just to see if I could still get a sound out of it. I could. But it turned out that a sound was all I wanted, and my flute deserved more attention, certainly less neglect. Not wishing to wait for a buyer, I searched for an appropriate local charity and found one in Play On, Philly, which provides music education to students from Kindergarten through Grade 12. Just before the flute left my long and fitful stewardship, I noodled with it one last time by playing along with one of Rahsaan Roland Kirk’s earliest tracks, a 1956 recording of “Triple Threat” on which no flute is heard – except for mine.

Taking everything into account, it was worth the time and — guess what, Dad? — the money, too.

March 22nd, 2013 — jazz reviews

A big shout out to those of you who responded to the previous post on Thomas Chapin’s newest CD set, Never Let Me Go. Lots of love out there for Tom, who deserves all that & more. Among the many who responded: Stephanie J. Castillo, who is trying to pull together enough funds for a full-length documentary about Tom. Here is the site — with all the information on the Kickstarter campaign & every important link related to Tom Chapin’s life & legacy.

Whatever you can do, patrons. The Home Office will be grateful. The campaign has roughly a week to go & they’re still not near the goal of $50,000. So she’s asking people to take part in the “100 X $100 Group Give.” Do the math. If 100 people give $100 over the next five days, $10,000 from the Group Give will help meet the $50,000. Of course, all amounts – small and large — will be accepted.

The previous post said mostly everything I needed to say about Tom…except, maybe….

OK, bear with me. In February, 2008, a memorial concert for Tom was staged at the Bowery Poetry Club. There was more than enough words & music to share that night. But I felt somewhat bereft, being only a spectator & knowing Tom as I did. It wasn’t until a couple days afterwards that the following fantasia rolled out of me. I wish it had rolled out that evening, but I guess it wasn’t ready.

So with your kind indulgence, here’s that side-dish of speculation mentioned on the marquee, a meeting that never happened, but should have. It’s a little wig-bubble The Home Office is labeling:

WHEN MILES MET TOM or THE FINAL FRONT LINE

It’s September of 1991 and a gravely ill Miles Davis is, as Lord Buckley would put it, not merely “on the razor’s edge”, but on the “hone of the scone,” whatever that is, if that is what it is.

Anyway, Miles is in his Malibu manse, semi-conscious, hooked up to all manner of wires and tubes. Deep down, he knows that this is all pointless. It definitely feels like Checkout Time’s arriving at any minute and all he can do is drift in and out of reality, trying to take in as much as he can before the lights go completely dark.

He can dimly hear a radio piping in music from another room. Some dumbass has it tuned to a jazz station. Fuck that, Miles thinks. Anything but that! And it’s not just plain old jazz, but that squealing and squawking shit that Trane helped spread like a virus. I do not need that shit taking me out. I’ll take Manto-fuckin-vani over this!

Just like that, his espresso eyes, which were starting to cloud over mere seconds ago, sharpen into hard, clear points as he hears this gorgeous, passionate alto sax solo soaring and slicing its way through the miasma. He’d love to sit up so he can hear better and, to his astonishment, he almost feels as though he could. The keening, probing sound continues to jab its way into his consciousness. He digs the raw aggression, the rippling arpeggios and, more than anything else, a tone that sounds the way light would sound if light could make sound. Mothafucka can play his ass off!!

At that moment, a male nurse walks by his bed. Miles emits soft murmurs, which is the best he can do. The nurse doesn’t hear anything. Drastic measures are called for, so Miles attempts to simulate some sort of spasm. It’s lame, but it works. The nurse walks over.

“Miles?,” the nurse whispers.

“Hmmrefffrrr,” Miles says.

“I’m sorry. Do you need anything?”

The music’s almost over. If only someone would take these tubes out of his goddam nose…

“Mwhegfffrrgggrdr.”

“Mister Davis,” the nurse leans close to the parched, scarred lips. “I still can’t…”

A raspy bullet, whatever’s left deep inside him, is violently pumped through his ravaged larynx into the idiot’s ear

“I SAID, who’s that on the mothafuckin radio, goddammit!”

After a series of confusing exchanges, someone else in the house, presumably whoever had the radio on, finally figures out what Miles wants to know. He tells him that there was this bootleg tape of a young reed player out of New York, used to play with Lionel Hampton, but he’s just starting to make a name for himself in the downtown scene. Album’s not even out yet…

Miles can sense the steam rising within him. It feels good, almost human, but he still sounds exasperated and weak at the same time. “Who…is…that…motha…fucka?” Serious coughing, maybe a trickle of blood…

The name, the fool says, is Chapin. Was that his first or last name? Oh, right. Yeah, Tom. Thomas Chapin…

Orders are rasped. Call that station! Get a copy of that tape! Find out where that mothafucka lives! Now, goddamit! And so on…

Sooner than it’s possible to imagine, given the circumstances, Miles is on a long-distance call with Tom, who thinks at first that someone’s fucking with him. When he realizes, it’s not a joke, he thinks: Oh, my God! I’m on the phone with Miles Davis! And he sounds TERRIBLE…

“Lissen, man,” Miles says weakly, gasping for air, “how soon can you get your ass out here? With…that…sax…”

“Um,” Chapin says, not sure he heard correctly, but he answers anyway. “I dunno, Mister Davis, when do you…”

“Now! Yesterday! Last week, goddammit! I’m dyin’ out here, man! I want…(wheeze)…I want to record with you…Just for one time…”

Chapin is now certain someone’s messing with his head, big-time. He observes, tentatively, delicately that Miles may not…make it…by the time he flies to L.A. even if he leaves that second…

“Well, then you better hurry your ass up” Click.

From here, it’s too quick and hazy to keep track, but Thomas Chapin has somehow made the next flight from JFK to LAX. Miles, or someone close to him, takes care of traveling expenses and studio time.

Time movies fast. Here’s the studio, but where am I, Chapin wonders. Is it dawn or dusk? Where did this rhythm section come from and how many of them are there?

Miles is wheeled into the room, connected to a respirator. There’s no way, Chapin thinks. But the horn is in Miles lap, poised for action. Miles, forgoing amenities, croaks out the only three words he will say to Tom Chapin all day:

“Follow…my…lead.”

What follows is the kind of music that wills itself forward without stopping for thought or breath. It free-associates itself into something that’s neither funk nor free, neither “inside” nor “outside”, neither modern nor post-modern, neither swing nor rock; more to the point, it’s none of these things exclusively but a dense, yet buoyant amalgam of mid-to-late-20th century music’s varied precincts, high, low and in-between. It is, in other words, music that only Miles Davis could have set in motion – and that only Thomas Chapin’s luminous tone and inquisitive chops could help him finish.

Ten hours and six tracks later, the last testament of Miles Dewey Davis is in the can. He returns to Malibu to await the final call, which comes as Tom is in mid-air somewhere over western Pennsylvania on his way back to the city…

The session? Well, you know what happened with that session. By now, everybody knows what happened with that session and how it helped make jazz’s next century a …But that’s another fantasy, isn’t it?

March 20th, 2013 — jazz reviews

The first time I heard him play was sometime in 1988 on an LP (ask your parents, kids, because I hear they may be coming back) entitled, The Sex Queen of the Berlin Turnpike, a jazz-and-poetry mix written and produced by a central Connecticut crony of mine named Vernon Frazer, novelist, raconteur, boxing aficionado and bass player who’d provided musical accompaniment to his readings here and, in years to come, at such venues as the Nuyorican Café and the Knitting Factory.

As I listened, I became acutely aware of this flute coiling around Vern’s incantations and bass lines in lucid, deceptively simple patterns. As I grew up a flautist manqué, however reluctantly, I paid attention when people did unexpected things with the instrument, especially in jazz. And whoever was playing had nailed down a lyrical, probing style that refused to lean heavily on the flute’s naturally pretty tone. (The tone wasn’t pretty. It was beautiful, rich and – was it possible? – evenly layered.) And then I heard the alto sax solos. They could burn like scalding water. But they also soared; sometimes like jets, other times like gliders. More than anything, it was the relentless invention, the let’s-try-anything ingenuity that knew how to swing, bop and blow the blues in the grandest manner, but could step “outside” conventional changes with a nonchalance that seemed highly evolved even for the greyest of beards.

I checked the name on the cover: Thomas Chapin. Hadn’t heard of him before that point and was chagrined at myself for not paying attention. I’d assumed he was this lesser-known veteran of the black music wars who likely spent the previous decade-and-a-half trolling through lofts along the eastern seaboard. “Who is this Thomas Chapin cat?” I wrote Vern, who in turn told me he was this barely-thirty-something white guy from Manchester, Connecticut.

Manchester? Really? I’d spent part of my early newspaper years writing about that east-of-the-river suburb and, whatever its myriad virtues and defects, the next-to-last thing I’d have expected was someone who could wail like this. When I played this record to another colleague from those long-ago Hartford Courant days, his head swiveled as sharply as mine had to the sound of Chapin’s alto. When I told him who was playing and where he was from, my friend shook his head. “Shit, man,” he said. “Nobody from Manchester ever blew like that!”

It’s been fifteen years since Thomas Chapin died at just 40 years old and I still find myself wondering what he’s been up to. I keep thinking he’s got to be on some club’s weekend schedule, leading a trio or quartet in support of a new disc or performing yet another homage to his idol Rahsaan Roland Kirk. No matter where Tom would be, he would be turning heads, winning friends, encouraging people to come over to his side, no matter how forbidding or unconventional the setting. That’s what he always did, on- or off-stage. That’s why we miss him.

He was a member in good standing of the crowd of cutting-edge dynamos who waved the progressive-jazz banner throughout the eighties and nineties in downtown New York (a scene whose central HQ was that aforementioned Knitting Factory). Yet he also turned heads among more-traditional-minded listeners as a distinctive and highly accomplished post-bop player with a bright, lightly jagged tone and a prodigious, often-stunning range of expression. As with generations of musicians who had apprenticed under Lionel Hampton (in whose big band he’d worked for five years), Chapin carried “Gates’s” lessons of brash showmanship in his own trick-bag. But he never pandered to or shortchanged expectations, whether swinging from the core of a hard-bop standard or generating torrents of chromatic density off a simple riff.

The straight-ahead side blooms like fireworks on Never Let Me Go (Playscape), a recently-released triple-CD of Chapin leading quartets at two New York venues. The first two discs are from a November, 1995 show at Flushing Town Hall with pianist Peter Madsen, bassist Kiyoto Fujiwara and drummer Reggie Nicholson. The third disc teams Chapin and Madsen with the bass-drum tandem of Scott Colley and Matt Wilson at the Knitting Factory on December 19, 1996 – Chapin’s last live date in New York City. (He’d been diagnosed with leukemia the following year.) Though Chapin’s last studio recording, 1997’s Sky Piece, remains the one true gateway to his life’s work, Never Let Me Go evokes the warmth of Tom’s personality and the exhilaration he could communicate even to those who may not have fully appreciated his chosen idiom.

Ecstasy leaps from the first track, “I’ve Got Your Number,” whose chord changes provide a gauntlet for Chapin’s breakaway speed and power. There was never anything tentative about his attack; not even when, on the silky “Moon Ray,” the tempo gears down to stealth mode and Tom summarily shifts to shrewder thematic tactics. Along with his many other gifts, Chapin easily complied with Lester Young’s directive to “sing a song” when he played – which meant, as Prez suggested by example, to find the songs within the song that needed to come out. More than most of his downtown confreres, Chapin always exercised this prerogative, even on songs that weren’t part of the classic-pop canon as exhibited here on both “You Don’t Know Me” and “Wichita Lineman,” whose melodies Chapin irradiates with such conviction that you get the feeling he could have, in time, single-handedly embedded them both in the traditionalist fake-book.

His own compositions become occasions for Chapin’s more imaginative dramas of harmony and rhythm doing their approach-avoidance ritual. These are most prominent on the Knitting Factory gig; it must be noted that Matt Wilson, whose own embraceable style and personality are mirror images of Chapin’s, opens wider terrain for both Madsen and Chapin to lunge at the edges of time and space. On such pieces as “Big Maybe” and “Flip Side,” whatever ambiguities, discordances and incongruities play their way through each solo do so from a solid core, which Wilson tends with inviolate calm, but also with a gentle persistence of vision. Madsen makes his presence even more pronounced on the latter set; he builds his own model airplanes to fly as eccentrically, yet as emphatically as Chapin’s own. Together, this group could have helped make the cutting-edge a place where all would be welcome, exalted and, eventually, transformed. It’s nice to think so anyway.

When someone dies as prematurely as Chapin, there usually come in his wake several voices inspired by his example to fill the void. (Think of all those bright, hot horns who picked up where Clifford Brown left off. Or all those actors who are still filling in the blanks left behind by James Dean’s car crash.) In the decade-and-a-half since Chapin’s death, those examples are harder to find, especially his ability, or more accurately, his impulse, to bridge the gap between progressive and traditional jazz music – or to, at the very least, extend what critic Jim Macnie characterized as the “dialogue” between two wary, warring factions. As jazz kept shifting shape at the close of the century, bending and twisting itself into new forms while struggling with how much of its past forms it should retain (or shed), Thomas Chapin offered a model for the music’s future by making his own art pliant, inquisitive and open enough to accept whatever the times demanded. I don’t know whether the “amalgam of freedom and discipline” described in Chapin’s Allmusic.com biography could have slowed down or even stopped jazz’s free-fall in a music marketplace that became even more mercurial after his death. But I’m far from alone in wishing he’d had more time to try.