Because I don’t have to, I’m not going to bother with a Top-Ten movie list this year. This is also because there wasn’t a whole lot I saw at the multiplexes in 2014 that got me as wound up as the stuff I’m listing below. And if I bothered to enumerate the movies that did, I’d likely end up with a list that more or less looks like everybody else’s, which precisely none of us wants.

Instead, I’m going to pull together a rag basket of items that for various reasons made the most resounding connections with my frontal lobes through the prevailing media din of weapons-grade white noise and free-styling schaudenfreude. Most came out this year; some didn’t, but I got around to them for the first time this year, so they count. (My list, my rules.)

Quite likely, I’m forgetting, or blocking some stuff. It’s been that kind of year. And there were some things I couldn’t bring myself to include, whatever my absorption level. Scandal, to take one example, remains for many people I trust an irresistible sack of Screaming Yellow Zonkers. But outside of Joe Morton’s righteously Shatner-esque scenery chewing and the mad electricity vibrating in Kerry Washington’s eyeballs, I’ve found that its live-action anime antics can go on without me for at least a couple weeks at a time.

So anyway…(as this fellow might out it)

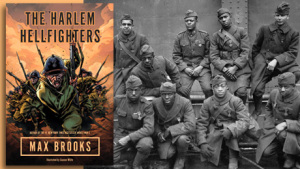

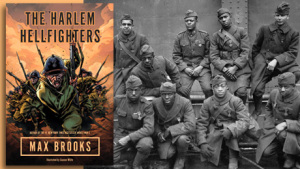

The Harlem Hellfighters by Max Brooks –Brooks made his name mythologizing the walking-dead (World War Z, The Zombie Survival Guide). But he proves himself just as conscientious in rendering factually grounded savagery in this fire-breathing graphic (in every sense) novel about the legendary all-black 369th Infantry Regiment that roared out of Harlem to fight in World War I, the hinge between post-Reconstruction’s legally-sanctioned terrorism of African Americans and the gathering pre-dawn of the civil rights movement. Though the Hellfighters’ passage from raw, often humiliated recruits to take-neither-prisoners-or-shit-from-anybody warriors is rousing, the visual depictions of squalor, disease and violence (thanks to the classic-war-comics élan of illustrator Canaan White) deepen the many ironies layered onto this saga; not the least of which was that it was only through the horrific, demeaning process of war that black men could begin proving their worthiness as American citizens – and even that wasn’t enough. To establish its own validity as historical fiction, Brooks’ account brings in such real-life badasses as James Reese Europe, Henry Lincoln Johnson and Henri Gouraud for colorful cameos. Of course, a movie is planned. Good luck trying to top this

Scarlett Johansson –I’ve already waxed rhapsodic about the commanding way she works the alien-enigmatic in the polarizing Under the Skin. By contrast, the art-house crowd showed relatively little-to-no-interest in Lucy in which she played a hapless, sponge-faced drug mule accidently injected with a drug transmuting her into a time-distorting, matter-altering, ass-kicking wonder woman. But Luc Besson’s acrylic pulp fantasy proved that few, if any movie actresses today are as cavalierly brilliant at throwing down wire-to-wire magnetism in such nutty eye candy. Manny Farber would have wallowed in the termite splendor of it all. Even her by-now borderline-gratuitous Black Widow turn in support of yet another Marvel money machine (Captain America: The Winter Soldier) retained enough droll slinkiness to make one suspect that giving the Widow her own vehicle might be a bit of a let-down. Then again, Ms. Scarlett never let me down once this year, so why dwell upon the purely speculative?

Whiskey Tango Foxtrot By David Shafer – This novel took me by surprise as it did several other critics this past summer. Up till that point, it hadn’t occurred to me that the legacies of both Richard Condon and Ross Thomas could, or even should be filled. Nevertheless, anyone whose familiarity with these authors’ works extends beyond Condon’s The Manchurian Candidate or Thomas’ The Fools In Town Are On Our Side will recognize Shafer’s sardonic humor, crafty plotting and humane characterizations as reminiscent of both authors – which is another way of saying these qualities aren’t what readers of contemporary techno-thrillers are used to. Also, much like Condon, Shafer knows, or strongly suspects, what we’re all afraid of, deep down, and finds a surrogate for this fear that’s both outrageous and plausible; in this case, a sinister cabal of one-percenters planning to seize total control of storing and transmitting information worldwide, thereby making recent abuses by the NSA, or whoever has it in for Sony Pictures, seem like benign neglect. This premise scrapes somewhat against territory controlled by what used to be called the “Cyberpunk School” as well as Thomas Pynchon, except that Shafer’s three 30-ish hero-protagonists are at once unlikely and recognizably human: an Iranian-American NCO operative who stumbles into the conspiracy so haphazardly she’s not sure what it is until it goes after her family, a self-loathing self-help guru in debt to his eyeballs who’s recruited by the cabal to be its “chief storyteller” and his estranged childhood friend, a substance-abusing misfit with a trust fund as thick as his psychiatric case file. They are all swept into an underground movement called “Dear Diary” which knows what the cabal is up to and is deploying its own secret network to bring it down. Social comedy, political melodrama and digital menace don’t always blend as well as they do here. And this is only Shafer’s first novel, meaning, as with the other masters cited above, he can only get better at this stuff from here on.

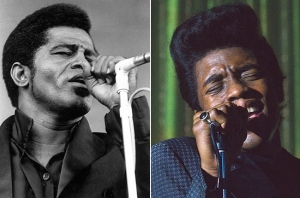

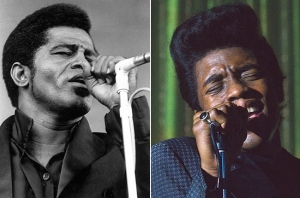

Get On Up & Mr. Dynamite: The Rise of James Brown – The former is a feature biopic; the latter an HBO-exhibited documentary. Both told me things I didn’t know about their shared subject – or, maybe more to the point, framing what I already knew about James Brown’s story in a manner that showed him as far more than an unholy force-of-nature. If I lean more towards the documentary, it’s because the revelations are more striking (not just the spectacular “what” of Brown’s showmanship, but the painstaking “how” of its components along with its savvy adjustments over time). And its testimonies are altogether more enlightening (Mick Jagger, who co-produced both, sets the record straight on how the “T.A.M.I. Show” sequence of acts really went down) I loved listening to band members let loose on what they really thought of their sometimes thoughtless boss as well as what second-generation Fabulous Flames as Bootsy Collins learned on and off the road from Brown. Tate Taylor’s biopic has a different agenda, but it strives to be just as faithful, if not always to the facts, to the facets of Brown’s fiery, hair-trigger temperament. Maybe it tried too hard. (As far as B.O. was concerned, Get On Up…didn’t.) But Chadwick Boseman’s, conscientious rendering of Brown’s tics and turbulence is almost as breathtaking to watch as one of the Godfather’s actual Soul Train appearances. Now that Boseman’s successfully portrayed two historic icons, I remain anxious to see what he can do with a Regular Guy role sometime between now and Marvel’s Black Panther movie.

FX– The third, and best, season of Veep; the harrowing, jaw-dropping single-take night scene in True Detective; Billy Crystal’s astute, heartwarming 700 Sundays; Girls and its discontents; the sheer how-can-it-possibly top-itself-again-and-again momentum of Game of Thrones…There was so much to love about HBO this year that I feel like an ingrate for professing my affection for a rival, even though there are things in both FX and HBO that I’ve neglected (American Horror Story, Boardwalk Empire) or shortchanged (The Strain, The Leftovers). Nonetheless anyplace I can find Louie, Archer, The Americans and (for me, especially) Justified is a cozy, stimulating home for my mind. Add to this the deep-dish pleasures of Fargo, whose greatness sneaked up on me the way Billy Bob Thornton’s meatiest, slimiest character since Bad Santa slithered through the frozen tundra, and of The Bridge, whose shrewd and nervy evolution from its first, somewhat derivative season went mostly unnoticed by the professional spectator classes and I’m not sure FX doesn’t have a deeper bench, pound for pound, than its bigger rivals., I prefer a lean, mean FX that takes so many worthy, edgy chances that it can be forgiven for something as lame and sad as Partners. (Never heard of it? Good. We shall speak no more.)

The Oxford American “Summer Music Issue” – I, along with many of my friends, have lots of reasons for being mad at the once-and-future Republic of Texas. But I still love its literary heritage and, most especially, its thick, spicy blend of home-grown music, which takes up C&W, R&B, Tex-Mex, swing, funk, hip-hop and even some avant-garde jazz courtesy of native son Ornette Coleman. They’re all represented on a disc accompanying a special edition of this always mind-expanding quarterly. Compiled by Rick Clark, this CD provides the kind of kicks your smarter buds used to slap together on cassette as a stocking stuffer. Besides the aforementioned Ornette (“Ramblin’”), there’s some solo Buddy Holly (“You’re the One”), early Freddy Fender (“Paloma Querida”), priceless Ray Price (“A Girl in the Night”) and the unavoidable Kinky Friedman (“We Reserve the Right to Refuse Service to You”). The left-field surprises include an especially noir-ish take of Waylon Jennings doing his signature “Just To Satisfy You,” a deep-blue rendition of “Sittin’ On Top of the World” by none other than Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys, Ruthie Foster’s espresso-laden performance of “Death Came a-Knockin’” and Port Arthur’s own Janis Joplin fronting Big Brother and The Holding Company on a “Bye, Bye, Baby” that swings as sweet as Julio Franco once did. I don’t want to shortchange the actual magazine, which includes James Bigboy Medlin’s reminiscences of working with Doug Sahm, Tamara Saviano’s portrait of Guy Clark and Joe Nick Patoski’s story about Paul English, Willie Nelson’s longtime drummer. It doesn’t beat a spring-break bar tour of Austin, but it’ll do until I get a real one someday.

A strange year, an exasperating year; maybe even an ominous one for jazz music’s already diminished stature in the marketplace. First this happened, followed closely by this. And then this came up and so did all the resulting cawing and cackling on the social media sites. When you add the very public, free-falling disgrace of the nation’s leading — or, at the very least, most famous — jazz devotee, you may as well shrink wrap and label 2014 as a bummer despite the varied finery listed below.

And I know what you saner, stoic ones are going to say: That a list such as mine, or anyone else’s, represents the best possible counterargument to the signifying-nothing that is sound-and-fury, on- or offline. Art doesn’t care what the Washington Post or New Yorker says or does – or mostly doesn’t. Art walks its own serene path through the fire towards high ground. Art is a ninja-warrior aristocrat with two layers of body armor and an unrelenting poker face. Art would assure me, in firm, modulated timbres, that just because some people think jazz stopped being cool doesn’t mean it has.

Knowing all that, however, doesn’t improve my end-of-the-year mood; one that can’t be quantified as good or bad, but is, all at once, restless, melancholy, somewhat manic and predominantly wary. All told, I’m just a little anxious to see what’s coming next – in jazz and everywhere else.

You ask: Dread or hope? I say: Turtles are cool.

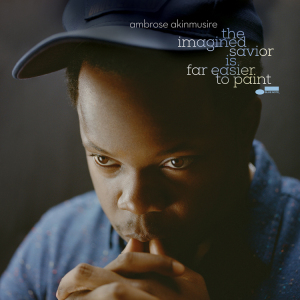

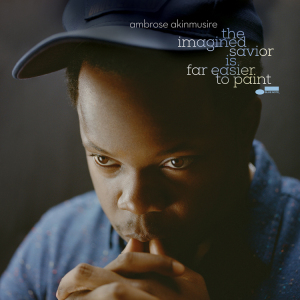

1.) Ambrose Akinmusire, “The Imagined Savior is Far Easier To Paint” (Blue Note) – As with its illustrious Blue Note predecessors from fifty years ago, Akinmusire’s second effort for the label meshes with the subconscious fabric of its turbulent times without needing to be explicit in its content (except when it chooses to do so). Just as Donald Byrd’s “A New Perspective,” which brought this into the world, is still redolent of all that America was going through in the early sixties, so do the somber, mostly minor-key soundscapes in “The Imagined Savior…” reflect present-day sorrow, regret and barely-contained anger with thwarted possibilities. The anger breaks into full, unfettered view in the sepulchral “Rollcall for Those Absent” on which the voice of young Muna Blake, backed only by Akinmusire’s keyboard and Sam Harris’ Mellotron is heard reading the names of young black men shot to death by police, including Amadou Diallo and Trayvon Martin, whose names are intoned more than once. That more names could have been added to this roll since it was recorded only enhances the disc’s up-to-the-minute capital. Adding to this Tapestry of Now is “Our Basement (ed)”, written and sung by Becca Stevens, which is told from the perspective of a homeless man. What counters the ruminative gloom and anxiety of these and other pieces is the vigorous musicianship displayed by Akinmusire as both trumpeter and bandleader. In both capacities, he has a fluid command of phrase that comes across the way electricity would if you could hold it in your hands. Whether letting fly with his regular combo, including front-line partner Walter Smith on tenor sax, or blending with a string quartet, Akinmusire’s horn reaches for and often achieves attributes of the human voice, a quality that clearly marks him as one with all the greats on his instrument who preceded him. If you wonder (as my erstwhile colleague and friend A.O. Scott does) if there are artists who can speak directly and indirectly to the Way We Live Now, look in this corner of the room and get to know its dimensions. Be advised: They can only get bigger from here on.

2.) Allen Lowe, “Mulatto Radio: Field Recordings 1-4 (or: A Jew At Large in the Minstrel Diaspora”)(Constant Sorrow 101) – In the 32-page liner notes accompanying this package, which constitute some of the finest music criticism I’ve read all year, Lowe begins by talking about his “strange encounter” with fellow classicist/bandleader Wynton Marsalis, with whom he dared discuss “the modernist implications of minstrelsy,” which Marsalis pointedly refused to engage since he’s predisposed to regard hip-hop in general and ”Gangsta Rap” in particular as “neo-minstrelsy” catering to racial stereotypes. Which was far from the point that Lowe was attempting to make in the first place. In the six years since that brush-off, Lowe, a polymath who’s as incisive with his shtick as he is with his sax, dove headfirst into what some would consider the mongrelized, or creole-lized foundation of 20th century popular music where shotgun-shack juke joints and free-swinging black vernacular found communion with the tunesmiths piecing together their slick contraptions on Tin Pan Alley, or in the Brill Building. The result of Lowe’s restless search for a proper response to Marsalis is this four-disc omnibus of mostly home-cooked sessions (Lowe lives in Maine) in which several traditions – gutbucket, gospel, early New Orleans, ragtime, bebop, stride, avant-garde, nightclub swing, noir soundtrack, beat poetry and backwoods country – are probed, prodded and often pulled inside out (so to speak) with an eclectic array of musicians from saxophonist J.D. Allen, trumpeter Randy Sandke and clarinetist Ken Peplowski to saxophonist Noel Preminger, pianist Matthew Shipp and singer Dean Bowman. Along with other reeds, horns and rhythm players, there’s also a tuba (Christopher Meeder), a fellow musicologist (Lewis Porter) who plays wicked piano, alone or accompanied, and – of course, what else? – a novelist (Rick Moody). Even some of the titles of these pieces – “Jim Crow Variations”, “The Discreet Charm of the Underclass,” “When My Alarm Clock Rings on Central Park West” (Lowe’s variation of “When it’s Sleepy Time Down South”) – are provocative, mischievous throw-downs to whatever passes these days for dialogue about jazz. And after a year such as this, the prevailing conversation can use some spritzing and shaking-up. (Don’t try to get this through Amazon or I-Tunes. You’re better off ordering it this way.)

3.) Sonny Rollins, “Road Shows: Volume 3” (Okeh/Doxy)— I’m well aware that we who worship at the Altar of the Colossus often get carried away. My own effusions are tempered by what a fellow patron said about the GLTS (Greatest Living Tenor Saxophonist): that he’s a lot like Mickey Mantle because their strikeouts can be just as spectacular as their home runs. Still, you have to believe me when I tell you that this third installment of recent live Rollins feels richer, goes deeper and is altogether more rewarding than its predecessors. And I say this as somebody who tried, at first, to distract myself from its lure by doing…well I don’t remember exactly. But I do remember feeling my head swivel sharply upon hearing Rollins’ variations on “Someday I’ll Find You,” the album’s second track, from a 2006 performance in Toulouse. This Noel Coward ballad begs to be crooned in the grandest of tenor styles. Rollins never croons, at least not here. He asserts the theme while veering ever so modestly off its edges to let you know what’s coming as soon as he retrieves center stage from guitarist Bobby Broom. When it’s his turn to speak, Rollins slides into the first bars of the melody, pulling at its corners before he really gets to work somewhere around the third chorus. (Or is it the fourth? Never mind.) He’s clearing away open spaces for whatever direction he wants to go. At one point, he’s playing with the harmonies in the grand modernist manner of pulling them apart and rearranging them in different patters; maybe he’ll become fond of a riff and run with it to see if it opens still more territory, making just enough room for one of his licks to leap into the sky if only so he can find out where it lands. He’s trying to figure it all out as hard as we are. That’s why we’ve borne witness all these years: To collaborate in his process and share his potential surprise with what’s disclosed. There’s plenty more enlightenment to be found on these arias. And, jumping back a couple metaphors, there’s not a strikeout in the bunch.

4.) Kenny Barron & Dave Holland, “The Art of Conversation” (Blue Note) – Barron has proven to be such a compelling partner in previous recorded colloquies with Stan Getz, Charlie Haden and Regina Carter that it’s a wonder it’s taken this long for him to have a sustained sit-down with the indefatigable Mr. H. To say their meeting doesn’t disappoint would be understating matters to a felonious degree. They engage in an organic, mutually respectful flow of ideas and storylines with each man giving leeway to the other seemingly by intuition more than design. They hit all the lights on such standards as Parker’s “Segment” (which, for this occasion, should have worn its alternate title, “Diversity”), Monk’s “In Walked Bud” and, especially, Strayhorn’s “Daydream.” The revelations are more pronounced when it comes to each player’s compositions: Barron’s “Rain” opens vistas of lyrical expression for Holland while the latter’s “Dr. Do Right” craftily indulges Barron’s affinity for the Latin beat. I’m especially partial to the opening track, Holland’s “The Oracle,” because it is so reminiscent of one of my all-time favorite trio albums of the same name led by the late great Hank Jones and featuring Holland and the also-now-departed Billy Higgins. That album is out of print. This one more than compensates for its absence.

5.) Marc Ribot Trio, “Live at the Village Vanguard” (PI) – I have for decades challenged those who love hard rock, but hate progressive jazz to imagine, when listening to an outer-limits tenor sax solo, that there’s an electric guitar laying down the same pipe. I’ve urged jazz heads to do the reverse for heavy-metal speed runs. No takers at either end. But who’s going to listen to me anyway? Better that they should all listen to this, because when guitarist Ribot, drummer Chad Taylor and bassist Henry Grimes Go Outside as did John Coltrane (“Dearly Beloved,” “Sun Ship”) and Albert Ayler (“The Wizard,” “Bells”), they don’t merely make my point. They drive it home like a high-performance car going down on a steep hill at top speed. This unit’s been mining such territory for some time now and the revelations burn hotter within the hallowed confines of jazz’s Holy Dive. Oddly enough, though, it’s when Ribot and company do a 180 and apply their eclectic chops to light-footed, more conventional renditions of “Old Man River” and “I’m Confessin’ (That I Love You)” that they really seem to be taking chances; each man carefully spreading their range onto these chestnuts without unnecessary spillage. Their solicitousness within the body of each song gives greater magnitude to what they do outside the lines. Just to re-emphasize: Anything that’s done to amplify the enigmatic, yet persevering legacy of Grimes’ old boss Albert Ayler is worth the investment of energy; theirs, and yours.

6.) David Weiss, “When Words Fail” (Motema) – Most of the music here is so buoyant and luminous that you would never guess that the project is haunted by sadness and loss. Trumpeter Weiss, whose myriad activities include leadership of The Cookers, a septet formed in tribute to Freddie Hubbard, composed most of the pieces on this disc and writes in the liner notes of a full year of sudden, deepening tragedy beginning with the death of seven-year-old Ana Grace Marquez Greene, daughter of saxophonist Jimmy Greene, in the December, 2012 Sandy Hook School massacre. The father of the Motema label’s founder passed away during the ensuing year as did such jazz luminaries as Jim Hall, Donald Byrd, Mulgrew Miller, Butch Morris, George Duke and Cedar Walton. And just weeks after this session was completed, its bassist Dwayne Burro, died from pneumonia. The title track, named for the beginning of a Hans Christian Anderson quote that ends with “music speaks,” is dedicated to Burro while “Passage Into Eternity” was written with the Greene family in mind.. Here and elsewhere, you expect something somber and funereal, but instead find lively, propulsive small-group jazz that gives off warmth while staying resolutely cool. When the world keeps saying, “No,” music as joyfully rendered as this insists on saying, “Yes.”

7.) Mark Turner Quartet, “Lathe of Heaven” (ECM)— Somewhere in the alchemic Ursula K. Le Guin novel that gives this disc its title, there’s a quote from Victor Hugo that describes dreaming as “nothing other than the approach of an invisible reality.” As with the book, much of the music on this album, Turner’s first as a leader in 13 years, shifts time and space while somehow remaining self-contained and grounded. Not since the passing of Joe Henderson has there been a narrative artist on tenor saxophone such as Turner, who, as with Henderson, makes his statements through stealth, cunning and patience, his phrases cohering into shapes that are at once familiar and esoteric. He finds in trumpeter Avishai Cohen a worthy harmonic partner in thematic expression; Cohen bringing a fiery, full-bodied tone to compliment Turner’s cool, dry musings. The overall pace seems locked in neutral, the better to allow the mercurial front line to simulate invisible realities, though the rhythm section of bassist Joe Martin and, especially, drummer Marcus Gilmore execute throughout a slipstream swing compatible with weaving dreams. You couldn’t call this a comeback since Turner’s been quite busy in many venues and combos. But having him return out front, so to speak, affirms the hopes he inspired a decade-and-a-half ago as a tenor player skating to a softer drumbeat.

8.) Steve Lehman Octet, “Mise en Abime” (PI) – Though not packaged as such, Lehman’s latest series of experiments in sound mosaics represents a kind of deep-space 90th birthday party for Bud Powell, given that at least two of the tormented bop genius’s pieces, “Glass Enclosure” and “Parisian Thoroughfare,” are so drastically reinvented as to be barely recognizable, except for the angular dynamics Lehman applies to their abstract designs. Because his intellectual qualifications are part of Lehman’s hype, you’re tempted to think of his work as composer, arranger and altoist in purely cerebral terms. But given his all-star lineup of some of the brightest young players (trumpeter Jonathan Finlayson, trombonist Tim Albright, saxophonist Mark Shim vibraphonist Chris Dingman and drummer Tyshawn Sorey among others), Lehman has too much firepower at his disposal to leave listeners on ice, so to speak. He’s so creative in his harmonic combinations and electronic enhancements that I’m a little curious to see what he does in more specified contexts; Christmas, say, or 1940s rhythm-and-blues, or the Sun Ra Songbook.

9.) Matt Wilson Quartet with John Medeski, “Gathering Call” (Palmetto) – I’ll just repeat what I posted back in January since a whole lot’s happened since then: Hard bop, late-1960s/early 1970s vintage, played without apologies and with an open-hearted joie de vivre that can make even the hardest of hard-core progressives wonder why they ever thought the genre was old news. I suppose some would still think it old news, even if they liked it. But there’s nothing musty or creaky about Wilson’s easygoing command of the trap set in all situations or his group’s saucy renditions of such Ellingtonia as “Main Stem” or “You Dirty Dog.” The quartet also pays homage to the recently departed bassist Butch Warren by playing the latter’s “Barack Obama” with the delicacy, wonder and cautious optimism you suspect the composer had in mind as he wrote it. You’re happy for the leader, one of the perennial Good Guys in the jazz business, which in turn makes you hopeful for the business itself.

10.) The Microscopic Septet, “Manhattan Moonrise”(Cuneiform) — Where in their 1980s flowering they suggested, as a perspicacious observer put it, a “wedding band from Mars,” these wily retro sharpies now look on the inside-cover photos of this disc like a weathered, motley council of wizards from a Tolkien homage hiding out from Sauron on a band bus touring the Dakotas in the winter of 1939. Yet even with added snow in some of their membership’s facial hair, the Micros still sound airtight, agile and ready for anything co-founders Joel Forrester and Philip Johnston toss into their playpen, whether it’s a funk stomp a la Johnston’s “Obeying the Chemicals,” a Monk-ish pastiche from Forrester, “A Snapshot of the Soul” or the snap-brim eminently danceable swinger, also from Forrester, that gives the disc its title. Cards on the table, I’m at a loss to explain what “MM” by TMS is doing here since it doesn’t exactly break new ground either for the group or for its genre. But it’s a genre that they, and they alone, own: Microscopic Septet music at its most proficient, inquisitive and enjoyable. There may have been more significant and ambitious albums I heard or missed out on this year, but few that had as much trouble staying out of my machines as this. Long Live The Micros! And Long Live Jazz – whatever the heck that means!

HONORABLE MENTION: “Frank Kimbrough Quartet” (Palmetto); Tyshawn Sorey, “Alloy” (PI); Regina Carter, “Southern Comfort” (Masterworks ); Omer Avital, “New Song” (Motema); Ron Miles, “Circuit Rider” (Enja); Keith Jarrett & Charlie Haden, “Last Dance” (ECM); Randy Ingram, “Sky/Lift” (Sunnyside); Jason Jackson, “Inspiration” (Jack & Hill); Matthew Shipp, “I’ve Been To Many Places” (Thirsty Ear); Richard Galliano, “Sentimentale” (Resonance); Aaron Goldberg, “The Now” (Sunnyside).

BEST VOCAL ALBUM: Kendra Shank and John Stowell, “New York Conversations” (TCB)

BEST LATIN ALBUM: Arturo O’Farrill & the Afro-Latin Jazz

Orchestra, “The Offense of the Drum” (Motema)

BEST REISSUE: John Coltrane, “Offering: Live at Temple University” (Impulse!)

HONORABLE MENTION: Charles Lloyd, “Manhattan Stories” (Resonance)