Back in the winter of 1993, I threw a newsroom tantrum over an article that appeared in Spy magazine under the title, “Admit It. Jazz Sucks.” Written by Joe Queenan, then riding the ascending curve as a go-to contrarian crank for major media outlets, the piece was a mordant rant against what he perceived as a stuffed-shirt conspiracy to shove jazz music down the zeitgeist’s collective throat.

Most readers, even those unsympathetic to Queenan’s sentiments (and no, he wasn’t kidding about those), found it relatively easy back then to take the whole thing as bilious faux-regular-guy philistinism and move on with their lives. But I’d come across this screed at a time when I was still struggling to convince my New York Newsday editors that jazz music deserved a broader, bigger regular presence in its pages. The last thing I needed to hear from a national magazine, ANY national magazine, was a brash, loud voice suggesting to the editors that, well, yeah, maybe we don’t need to deal with this intimidating, complicated, provocative music that isn’t even as popular as it used to be. In other words, I took the damn thing personally – and stomped my feet, bellowed out loud, pounded furniture, etc. to let everybody I worked for, and with, know of my purple-cheeked displeasure.

And another thing: How exactly did Queenan figure that jazz was this domineering entity imposing itself upon whatever culture he believed himself to represent? If anything, jazz was catching more hell from the mainstream than it was receiving. Why the hell didn’t Spy magazine pick on somebody/something its own size? On top of everything else, it wasn’t even funny. Or smart. Even one of my editors, a rock-and-roller who like to bait me with similar anti-jazz bombs, thought the piece was lame –and, therefore, not worth getting ulcers over.

Indeed, after I’d calmed down and realized that I was all alone not just in detesting, but even caring much about the piece, it occurred to me that the very lack of furor generated by the article was dismal proof that even if Queenan was right about this conspiracy, it was already failing.

So life did in fact go on: Spy eventually folded. Queenan wrote better, if more bilious pieces. Newsday ended its noble New York City-based experiment. And jazz still came out at the other end of the century barely breaking even in the music marketplace. So all I can say to all my friends and fellow-travelers in the jazz universe who’ve been seething since last week over what I’ve come to know as the “Unfunny Sonny” blog on The New Yorker’s web site is this: I been there already.

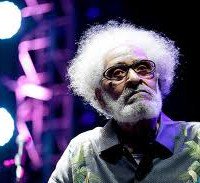

Briefly, for the rest of you: About a week ago (though it seems longer), a piece began circulating on the web under the New Yorker’s aegis under the title, “Sonny Rollins: In His Own Words.” Only it sure didn’t sound like Sonny Rollins; more like a whiny savant who likened the sound of a saxophone to a “scared pig” and doesn’t see the point of jazz and hates his whole life. “If I could do it all over again, I’d probably be a process server or an accountant. They make good money.” You get the idea. If you don’t, here’s the rest of it.

It now sounds weird, but more than a few people who first came across this thing on social media sites actually thought that this was Rollins’ voice. (I recall one musician first reacted by thinking that this outburst was the result of Rollins playing for too long with substandard backup musicians. Which was almost as funny – or not – as the piece itself.) As the civilized world now knows, a senior writer for The Onion named Django Gold wrote it and, as you’ll now notice, the blog now comes with disclaimers. Why? Partly because of this loud, resounding, universal outcry from the jazz musicians, fans and journalists that, collectively, made my office tantrum of twenty-one whole years ago seem like a sneeze in a noisy stadium. (By the way, after reading Gold’s piece again, make sure you watch this afterwards if only to make clearer whose voice is who’s.)

I suppose I, too, was more annoyed than amused by Gold’s little joke at jazz’s expense and the reasons are pretty much in line with those enumerated over the last few days. To wit:

1.) You mean The New Yorker no longer has the time or space to cover jazz on a regular basis and THIS is what they decide to contribute instead?

2.) Jazz is still fighting to hold on to its sliver of the music marketplace and here’s one of the leading publications in the country demeaning its greatest living improviser? How dare they! Would they do this to Tom Stoppard or Suzanne Farrell or anybody in opera?

3.) It’s not all that funny to begin with. Why waste the space, especially at jazz’s expense? I’m probably leaving out a few other complaints, but these three are among the more frequent, making it easier to take them each of them one at a time:

1.) That the New Yorker hasn’t bothered finding room for regular jazz coverage, especially after establishing a tradition for such through the late Whitney Balliett is, of course, an ongoing scandal. But no one else in the magazine world is bothering with it either. I can understand concerns among my fellow jazz lovers that the snide tone informing this parody will convince the music’s haters of their fine judgment and good taste. I don’t know. Outright jazz hate is annoying, but widespread indifference is worse. Does anyone besides me remember Stanley Crouch’s 2005 straight-ahead New Yorker profile of Rollins? Do I remember any profile of any jazz musician since then of similar heft and dimension? I do not. And whenever a newspaper or mainstream publication paid me to write about jazz, I often felt as if I were dropping pebbles down a deep, dark well waiting for the splash. I’d like to think the furor aroused by Gold’s prank would shame editors into changing this situation. I know better. They’d prefer more pranks. So does the Internet. So do the people who get caught up in the Internet. I play the sincerity card with jazz because I respect it too much to do otherwise. But when I praise Sonny Rollins, I’m basically telling people what they already know, whether they’ve heard him for themselves or not. Snide plays better than sincere. Or don’t you listen to “Wait, Wait, Don’t Tell Me” every week on NPR? Figured as much.

2.) Nevertheless, I, too, would rather read or write about the latest installment of Rollins’ “Road Shows” albums than see somebody reduce Sonny to the rough equivalent of a petulant preppie. I’ve often said that while critics sometimes pump up everything Rollins does with little discrimination, the public-at-large seriously underrates or altogether ignores his glorious inventiveness. (Those who wonder why everybody in jazz got so riled by Gold’s piece should immediately buy Road Shows, Vol. 3 or, to get it all over with, Saxophone Colossus.) On the other hand, Gold or his editors must already think that Rollins has the kind of heft and dimension as a figure to be poked at and hazed in the public square, which is kinda sorta a backhanded acknowledgment of his significance. Would somebody do the same to Tom Stoppard or Suzanne Farrell or anybody in opera? You bet your sweet ass somebody would, anybody would, early and often! To say that jazz can’t take even the most half-baked pies tossed at its kisser is to make it seem as reductive as snobs in the higher elevations of Culture Gulch believe it to be.

3.) Then, too, opera buffs and balletomanes in those higher elevations are often regarded as humorless wet blankets who can’t abide the cheap jokes as their expense. The jazz cognoscenti may even acknowledge the irony that its collective cri-de-coeur over Gold’s blog only confirms the outer world’s suspicions that we’re all a bunch of insular, thin-skinned spoilsports who can’t take a joke. But that the joke in question needed a disclaimer to chill out the complainers may prove that the joke in question wasn’t all that funny to begin with. For what it’s worth, it’s a helluva lot funnier than Queenan’s smug tirade, though, unlike Queenan, Gold doesn’t seem at all sure of what he’s skewering in the first place — and neither does the reader. It’s a piece interested more in striking a pose than making a point. It assumes an attitude about something that isn’t the least bit connected or concerned with what its satirizing; unlike Donald Barthelme’s New Yorker story, “The King of Jazz,” which was the kind of blithe-but-pointed mockery that only a true fan (which Barthelme was) could pull off. Nevertheless, given the new-school dynamics of media transactions, strike a pose conspicuously enough and most of the gawkers will believe you’ve made your point anyway. And while jazz fans are shamed by Gold, he’s not shamed at all. He’s hearing tinkling sounds – bells, coins — whenever somebody mentions his name. If taking Gold to task for demeaning jazz makes me look like a slow-burning Edgar Kennedy to his blithe Harpo Marx, I’d just as soon go back to bed and wait for the wind to die down.

All this said, I’m glad, and even proud, that jazz got on its hind legs and roared back at this squib. The furor wont raise the music’s profile any higher than it is now. Too many other things have to happen for that to change. But as with that Spy magazine assault long ago, the effects of which I think I’m finally over by now, jazz under whatever name in whatever state will go on, oblivious to whatever the lovers and haters say about it. As I said earlier: I been here before. So will the divine mysteries of music. And so, I trust, will writers who can riff, lick and even vogue better than…no, sorry. I’m not going to mention the name again. I’d rather give my remaining time to this guy –– and, just as I eventually did twenty years ago, move on.