December 18th, 2014 — movie reviews, on writing lit -- and unlit, TV reviews

Because I don’t have to, I’m not going to bother with a Top-Ten movie list this year. This is also because there wasn’t a whole lot I saw at the multiplexes in 2014 that got me as wound up as the stuff I’m listing below. And if I bothered to enumerate the movies that did, I’d likely end up with a list that more or less looks like everybody else’s, which precisely none of us wants.

Instead, I’m going to pull together a rag basket of items that for various reasons made the most resounding connections with my frontal lobes through the prevailing media din of weapons-grade white noise and free-styling schaudenfreude. Most came out this year; some didn’t, but I got around to them for the first time this year, so they count. (My list, my rules.)

Quite likely, I’m forgetting, or blocking some stuff. It’s been that kind of year. And there were some things I couldn’t bring myself to include, whatever my absorption level. Scandal, to take one example, remains for many people I trust an irresistible sack of Screaming Yellow Zonkers. But outside of Joe Morton’s righteously Shatner-esque scenery chewing and the mad electricity vibrating in Kerry Washington’s eyeballs, I’ve found that its live-action anime antics can go on without me for at least a couple weeks at a time.

So anyway…(as this fellow might out it)

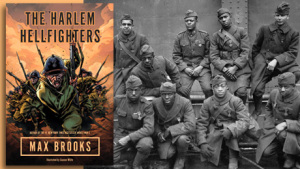

The Harlem Hellfighters by Max Brooks –Brooks made his name mythologizing the walking-dead (World War Z, The Zombie Survival Guide). But he proves himself just as conscientious in rendering factually grounded savagery in this fire-breathing graphic (in every sense) novel about the legendary all-black 369th Infantry Regiment that roared out of Harlem to fight in World War I, the hinge between post-Reconstruction’s legally-sanctioned terrorism of African Americans and the gathering pre-dawn of the civil rights movement. Though the Hellfighters’ passage from raw, often humiliated recruits to take-neither-prisoners-or-shit-from-anybody warriors is rousing, the visual depictions of squalor, disease and violence (thanks to the classic-war-comics élan of illustrator Canaan White) deepen the many ironies layered onto this saga; not the least of which was that it was only through the horrific, demeaning process of war that black men could begin proving their worthiness as American citizens – and even that wasn’t enough. To establish its own validity as historical fiction, Brooks’ account brings in such real-life badasses as James Reese Europe, Henry Lincoln Johnson and Henri Gouraud for colorful cameos. Of course, a movie is planned. Good luck trying to top this

Scarlett Johansson –I’ve already waxed rhapsodic about the commanding way she works the alien-enigmatic in the polarizing Under the Skin. By contrast, the art-house crowd showed relatively little-to-no-interest in Lucy in which she played a hapless, sponge-faced drug mule accidently injected with a drug transmuting her into a time-distorting, matter-altering, ass-kicking wonder woman. But Luc Besson’s acrylic pulp fantasy proved that few, if any movie actresses today are as cavalierly brilliant at throwing down wire-to-wire magnetism in such nutty eye candy. Manny Farber would have wallowed in the termite splendor of it all. Even her by-now borderline-gratuitous Black Widow turn in support of yet another Marvel money machine (Captain America: The Winter Soldier) retained enough droll slinkiness to make one suspect that giving the Widow her own vehicle might be a bit of a let-down. Then again, Ms. Scarlett never let me down once this year, so why dwell upon the purely speculative?

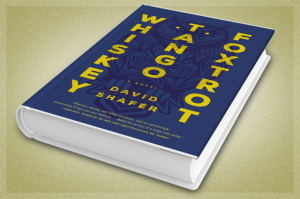

Whiskey Tango Foxtrot By David Shafer – This novel took me by surprise as it did several other critics this past summer. Up till that point, it hadn’t occurred to me that the legacies of both Richard Condon and Ross Thomas could, or even should be filled. Nevertheless, anyone whose familiarity with these authors’ works extends beyond Condon’s The Manchurian Candidate or Thomas’ The Fools In Town Are On Our Side will recognize Shafer’s sardonic humor, crafty plotting and humane characterizations as reminiscent of both authors – which is another way of saying these qualities aren’t what readers of contemporary techno-thrillers are used to. Also, much like Condon, Shafer knows, or strongly suspects, what we’re all afraid of, deep down, and finds a surrogate for this fear that’s both outrageous and plausible; in this case, a sinister cabal of one-percenters planning to seize total control of storing and transmitting information worldwide, thereby making recent abuses by the NSA, or whoever has it in for Sony Pictures, seem like benign neglect. This premise scrapes somewhat against territory controlled by what used to be called the “Cyberpunk School” as well as Thomas Pynchon, except that Shafer’s three 30-ish hero-protagonists are at once unlikely and recognizably human: an Iranian-American NCO operative who stumbles into the conspiracy so haphazardly she’s not sure what it is until it goes after her family, a self-loathing self-help guru in debt to his eyeballs who’s recruited by the cabal to be its “chief storyteller” and his estranged childhood friend, a substance-abusing misfit with a trust fund as thick as his psychiatric case file. They are all swept into an underground movement called “Dear Diary” which knows what the cabal is up to and is deploying its own secret network to bring it down. Social comedy, political melodrama and digital menace don’t always blend as well as they do here. And this is only Shafer’s first novel, meaning, as with the other masters cited above, he can only get better at this stuff from here on.

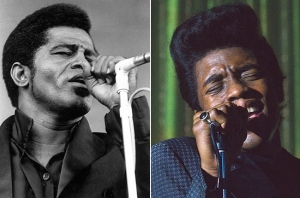

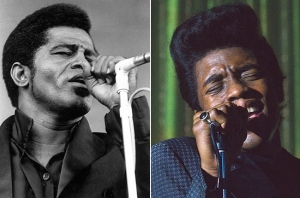

Get On Up & Mr. Dynamite: The Rise of James Brown – The former is a feature biopic; the latter an HBO-exhibited documentary. Both told me things I didn’t know about their shared subject – or, maybe more to the point, framing what I already knew about James Brown’s story in a manner that showed him as far more than an unholy force-of-nature. If I lean more towards the documentary, it’s because the revelations are more striking (not just the spectacular “what” of Brown’s showmanship, but the painstaking “how” of its components along with its savvy adjustments over time). And its testimonies are altogether more enlightening (Mick Jagger, who co-produced both, sets the record straight on how the “T.A.M.I. Show” sequence of acts really went down) I loved listening to band members let loose on what they really thought of their sometimes thoughtless boss as well as what second-generation Fabulous Flames as Bootsy Collins learned on and off the road from Brown. Tate Taylor’s biopic has a different agenda, but it strives to be just as faithful, if not always to the facts, to the facets of Brown’s fiery, hair-trigger temperament. Maybe it tried too hard. (As far as B.O. was concerned, Get On Up…didn’t.) But Chadwick Boseman’s, conscientious rendering of Brown’s tics and turbulence is almost as breathtaking to watch as one of the Godfather’s actual Soul Train appearances. Now that Boseman’s successfully portrayed two historic icons, I remain anxious to see what he can do with a Regular Guy role sometime between now and Marvel’s Black Panther movie.

FX– The third, and best, season of Veep; the harrowing, jaw-dropping single-take night scene in True Detective; Billy Crystal’s astute, heartwarming 700 Sundays; Girls and its discontents; the sheer how-can-it-possibly top-itself-again-and-again momentum of Game of Thrones…There was so much to love about HBO this year that I feel like an ingrate for professing my affection for a rival, even though there are things in both FX and HBO that I’ve neglected (American Horror Story, Boardwalk Empire) or shortchanged (The Strain, The Leftovers). Nonetheless anyplace I can find Louie, Archer, The Americans and (for me, especially) Justified is a cozy, stimulating home for my mind. Add to this the deep-dish pleasures of Fargo, whose greatness sneaked up on me the way Billy Bob Thornton’s meatiest, slimiest character since Bad Santa slithered through the frozen tundra, and of The Bridge, whose shrewd and nervy evolution from its first, somewhat derivative season went mostly unnoticed by the professional spectator classes and I’m not sure FX doesn’t have a deeper bench, pound for pound, than its bigger rivals., I prefer a lean, mean FX that takes so many worthy, edgy chances that it can be forgiven for something as lame and sad as Partners. (Never heard of it? Good. We shall speak no more.)

The Oxford American “Summer Music Issue” – I, along with many of my friends, have lots of reasons for being mad at the once-and-future Republic of Texas. But I still love its literary heritage and, most especially, its thick, spicy blend of home-grown music, which takes up C&W, R&B, Tex-Mex, swing, funk, hip-hop and even some avant-garde jazz courtesy of native son Ornette Coleman. They’re all represented on a disc accompanying a special edition of this always mind-expanding quarterly. Compiled by Rick Clark, this CD provides the kind of kicks your smarter buds used to slap together on cassette as a stocking stuffer. Besides the aforementioned Ornette (“Ramblin’”), there’s some solo Buddy Holly (“You’re the One”), early Freddy Fender (“Paloma Querida”), priceless Ray Price (“A Girl in the Night”) and the unavoidable Kinky Friedman (“We Reserve the Right to Refuse Service to You”). The left-field surprises include an especially noir-ish take of Waylon Jennings doing his signature “Just To Satisfy You,” a deep-blue rendition of “Sittin’ On Top of the World” by none other than Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys, Ruthie Foster’s espresso-laden performance of “Death Came a-Knockin’” and Port Arthur’s own Janis Joplin fronting Big Brother and The Holding Company on a “Bye, Bye, Baby” that swings as sweet as Julio Franco once did. I don’t want to shortchange the actual magazine, which includes James Bigboy Medlin’s reminiscences of working with Doug Sahm, Tamara Saviano’s portrait of Guy Clark and Joe Nick Patoski’s story about Paul English, Willie Nelson’s longtime drummer. It doesn’t beat a spring-break bar tour of Austin, but it’ll do until I get a real one someday.

September 10th, 2013 — TV reviews

Maybe if Jane Fonda had been allowed to channel her third husband when the series started, as opposed to its last couple weeks, more people would say nice things about The Newsroom. As it is, Aaron Sorkin’s unwieldy hybrid of screwball workplace comedy and tag-team poly-sci seminar will wind up its second season this week so distant from the zeitgeist that even people who like the show don’t talk about it much. And when they have lately, it’s to express some degree of disappointment with it, e.g. it’s gotten too slow, too solemn or too much like regular TV, only with more profanity, sex and drugs (and far less of the last two than in Season One). The haters, though yielding a tad more slack to Season Two, say pretty much what they said a year ago – and they keep finding new ways to hate what they see, even though they keep watching anyway.

It’s too bad the crowd has receded. Because after an erratic, even disquieting start, The Newsroom’s second season has brought forth some of the finest work released under Sorkin’s name since The Social Network. And I’m thisclose to declaring this year’s seventh episode, “Red Team III”, better than most of The West Wing during Sorkin’s four-year tenure as executive producer. Directed by Anthony Hemingway (Red Tails, The Wire), “Red Team III” climaxed the season’s running story in which producers, staff and anchors for the mythical Atlantis Cable Network are being deposed by the network’s attorney (Marcia Gay Harden) to prep for what’s been hyped as a potentially devastating lawsuit against ACN; all having to do with an American military operation code-named “Genoa”, which the network reported had deployed chemical weapons against Pakistani civilians. Though second- and third-guessing elements of the report assembled by an ambitious producer (Hamish Linklater), the ACN’s Big Three of anchor Will McAvoy (Jeff Daniels), news director Charlie Skinner (Sam Waterston) and producer Mackenzie McHale (Emily Mortimer) sign off on the story, which nets them their biggest ratings haul in years – and turns out to be completely untrue.

It’s only in this episode that the plaintiff in the lawsuit is disclosed as the report’s justly-fired-and-discredited producer, who claims he’s being scapegoated for what’s labeled “institutional failure.” Apparently, this also encompasses all the mostly embarrassing stuff that’s taken place throughout the year, much of it courtesy of whatever’s meant by “new media”: the on-line nude photos of ACN’s resident brainiac Sloan Stevens (Olivia Munn); the ongoing fallout from the YouTube-d video of a tour bus meltdown by staffer Maggie Jordan (Allison Pill) and other events whose deus ex machina value for Sorkin fit snugly with his show’s not-so-subtle disdain for all things digital, especially the Twitter-verse.

And yes, I know that it’s probably redundant in many minds to place “not-so-subtle” and Aaron Sorkin’s name in the same sentence. In the words of Anthony Lane, Sorkin “raises hectoring to the level of an art.” (One adds with due haste that Lane’s words weren’t applied to Sorkin, but to Jimmy McGovern, a British playwright, who, as with Sorkin, found his greatest notoriety in television while also establishing a reputation in theatrical film.) You have to be in the mood for hectoring and I guess I was in the mood for it last summer when The Newsroom’s first season tore through the TV set like a squall — accompanied, as squalls are, by intervals of humidity. Sorkin’s alternate media history of 2010 was pissed off in general about the same things I was pissed off about during the presidential election summer; which was why, despite the contrary opinions of critics I respect, I bought the whole grandiloquent package. If Sorkin wanted to rant about the decline of civility in public discourse, the cheapening of what used to be considered “news value” and the manner in which presenting facts in a reasonable, even balanced manner could be construed by right-wing fanatics as “slanted,” I was OK with it – up to a point.

That point converged primarily upon women. With the possible exception of Munn’s Sloan (who makes wonky social awkwardness a variable of imperturbable hotness), just about all the principal women characters in The Newsroom’s first season were hyperbolic, dysfunctional, manipulative or some annoying compound of the three. The exceptions were the near-anonymous support staff members with names like Tess (Margaret Watson), Tamara (Wynn Everett) and Kendra (Adina Porter), all of whom seemed composed, competent and fretless. We were kept in the dark about their private lives and I wish the same were true with everybody else in the cast, especially Maggie, her ex-boyfriend Don Keefer (Thomas Sadoski) and her would-be boyfriend Jim Harper (John Gallagher Jr.), who now has a thing for on-line political reporter Hallie Shea (Grace Gummer). Do I like these people? Mostly, I guess. Do I care whether any of them hook up? I do not. I prefer they all put their heads down and get to work the way Tess, Tamara and the others do. And while I understand Will and Mac’s relationship to be the series’ linchpin, I’m so indifferent to their will-they-or-wont-they-reconcile-after-their-bitter-breakup subplot that I’d now rather they never ever get back together…which for all I know may well be how this second season pans out.

What did pan out for certain this season – eventually – is that people on the show were concentrating much more on their work. Operation Genoa may have ruined ACN’s credibility. But it released The Newsroom from its frantic obligation to reboot recent history; just as well, too, judging from the peculiarly ambivalent way the show approached the Occupy Wall Street movement earlier this season. In the process, the women were generally smarter and stronger than last season. Harden’s droll, satiny portrayal of the company attorney provided one of Season Two’s recurring pleasures. Gummer’s character confuses me a little, but I thought her poker-faced autonomy was exactly what Jim had coming to him. I also wanted more of Constance Zimmer’s spiky communications director for the Romney campaign, thinking that if Sorkin insists on finding romance for McAvoy (a.k.a. Hamlet the News Lug), she’d be what government jargon would insist on labeling a “viable option.”

But the most gratifying change from last year has come from Mortimer. Her Mac McHale blossomed this season from a welter of mannerisms and nervous tics into a woman who, when she slows her roll long enough to stare at, or down, a situation, lets you see the rueful wisdom earned with her wounds. Sorkin’s scripts still make her steer cars into curbside garbage containers and induce gibbering noises from her whenever she thinks about the used-to-be that was Will-and-her. But even before she sussed out the fatal flaw in the Genoa story, Mac was showing more self-possession under stress.

I think both she and the show reached a turning point in this season’s fifth episode when she scolds a gay Rutgers student about to come out to his parents on the air during a segment of Will’s show about the Tyler Clementi suicide. One senses that it’s Sorkin’s voice one hears when she’s chiding the student for “bathing in the reflected tragedy” of someone who killed himself because his privacy was violated.

(Sorkin did a lot of this mouthpiece stuff throughout the first season and for much of this one. I admit it. It got old for me, too.)

“I just wanted a way of coming out to my parents without being in the same room,” the student then tells Mac.

“Well, good luck with that,” she says, then, trying to reassure him. “It gets better.”

“How would you know?” he replies.

“I guess I wouldn’t,” she concedes.

Which says to me that, at last, The Newsroom is thinking through things before, and maybe even instead of, emptying its rounds. I wish cable news and new media in general would follow this example.

And if The Newsroom continues to deepen its inquiry into the post-Millennial news business, I hope it hits harder than it has so far upon the whole notion of a 24-hour news cycle, which to my mind has done far greater damage to journalism than Twitter feeds. Whatever happens, the show still likely wont get more traction and attention than the last few episodes of Breaking Bad. I get it. I really do. There hasn’t been a single feature film I’ve seen this year that compares with what I’ve seen so far of Breaking Bad’s last mile. But somehow, it’s become so relatively unfashionable to like The Newsroom that I can see it becoming relatively fashionable again. Just as long as everybody on the show keeps their minds more focused on the news beyond their room.

August 31st, 2012 — Politics & Other Disappointments, TV reviews

I didn’t witness Clint Eastwood’s ride into Samuel Beckett territory last night as I had tickets to see the Best Team in Baseball play the Defending World Series Champions. I heard about it, though, the minute I came home from Nationals Park and patched into the digital hive-mind. And the chatter continues well past dawn (Oh the humanity!): The bitter laughter, the gnashing of teeth, the told-you-so smugness from the Clint haters juxtaposed with the exasperated Clint acolytes who have for decades defended his work despite his politics and whose reactions to last night’s monologue-with-empty-chair range from bemusement to avowals that they’ll never watch his Blu-Rays again.

As Marie Windsor, that great Mormon character actress, once muttered to a randy Jeff Bridges in Hearts of the West, “Lie down and cool off!” Those taken aback by Eastwood’s woozy-looking appearance should have taken the time yesterday afternoon to consult Christopher Orr’s astute preview charting the peripatetic course of Eastwood’s politics. (Note: I said “politics”, not “ideology.” We’ll discuss the distinction further along.) As Orr recounts, Eastwood has always been the Republican equivalent of a “yellow-dog Democrat”, i.e. someone who’d vote for a Democrat even if it were a yellow dog. Indeed, Clint’s been truer to the GOP than many a so-called Reagan Democrat insisting on being the “true” voice of the legacies of FDR, Truman, JFK and so on.

Still, for a lifelong Republican, Eastwood’s made some funny noises over time; the most recent of them coming in a Super Bowl commercial for Chrysler this past February with his “Halftime for America” narration that was so reminiscent of a Joe Biden pep rally that Karl Rove called him out for it. (All Eastwood had to do, apparently, was squint back at Rove to make Ol’ Turd-Blossom say nothing more about the matter.) He cops to being fiscally conservative, but is also pro-choice, pro-gay-marriage and, as his movies, musical tastes and inter-personal relationships prove, sympathetic to multi-cultural concerns.

In short, he’s a lot of things at once and no one thing in particular. When you smile and say, “Hello”, to Mr. Eastwood, you are greeting the American electorate itself whose politics are considered a personal, even an intimate matter because they come not from the brain, or the heart, but from the glands.

The extremist-libertarian Republicans who seek to squeeze Eastwood and, for that matter, the voters into their ideological camp are in for profound disappointment, no matter what transpired last night or will happen over the next couple months. This is because – and let’s read along slowly because some of you have trouble accepting this – America is not now and never has been an ideological country. Let me summarize:

Americans?

Ideological?

Antithetical!

No way!

Aint Happ’nin!

What do you want on your pizza?

Those liberal Lefties in whose consequentiality Newt Gingrich continues to invest a near-poignant belief stumbled into the aforementioned conclusion decades ago, but have yet to figure out what to do about it. Paul Ryan and company will assuredly discover the same thing. The only question being how much damage to Truth and Justice will be done by then.

As confirmation for the glandular state of political life, or at least, the perception of political life, one need look no further than Veep, the HBO sitcom starring Julia Louis-Dreyfus as a self-aggrandizing, self-sabotaging VPOTUS. As with many critics of the series, I had misgivings early on about the show’s sly avoidance of fixing Dreyfus’s Selena Meyer in any political party or (of course) ideology. Her pet causes – filibuster reform, the environment – are non-controversial and vaguely ecumenical enough not to distract from the office slapstick that’s the show’s principal attribute.

After several episodes (which I watched in repeats this past week mostly as refuge from Tampa’s muggy rhetoric), even these “issues” become less relevant than Selena’s slow-burning sense of personal affront at every staff blunder, mismanaged transaction and embarrassing gaffe. It’s not about oil or filibusters, dammit, it’s about me! How much more perfect the country would be if everybody was like me! No, not like me! Me! The late Gore Vidal, in his serene vanity, could relate to Selena’s frustration. And so, for that matter, could his old antagonist, William F. Buckley Jr. More to the point, so could most American voters for whom “issues” matter less than whatever it is matters to their own immediate needs.

I’m not saying there aren’t politicians whose actions, unlike Selena’s, are set in motion by something greater than their personal gratifications. I do think, however, that’s what the majority of Americans believe. And they will vote this fall out of the same soft-clay visceral instincts that, apparently, guide even a rock-ribbed, yellow-dog Republican like Clint Eastwood, who, like the Jazz Guy he is, makes his mind up as he goes along. So laugh or howl at the geezer babbling to an empty chair. Just know that you’re also laughing and howling at yourselves.