Once again, as was the case eight years ago, I find this year’s list to be leaning heavily on women. This time, however, I didn’t plan it that way. It’s just how it happened to work out. I suppose that’s where I’ve invested whatever hope I have for the future, long or short-term.

Nothing else to add, at least for now, except that I couldn’t get to as much out there as I would have liked.

Oh and, as always, these are in no particular order:

Colored Television – Percival Everett’s James was the Novel of the Year on most lists and, at this writing, it’s nestling in the upper tier of the New York Times Best-Seller List. It deserves every accolade it’s gotten. But so does the latest novel by Everett’s equally accomplished wife, Danzy Senna, who has built her own impressive reputation for acerbic comedies-of-manners as they evolve – or don’t – in the expanding new world of multiracial diversity in the USA. The protagonist of her latest novel is, like its author, a mixed-race novelist and college professor. Her name is Jane Gibson who, with her bohemian artist husband Lenny and their two children, ekes out a life on relatively meagre resources by inhabiting borrowed homes in fashionable SoCal neighborhoods. She puts all her faith and ambition in what she is certain is the Great American Mulatto Novel. (Yes, she prefers “mulatto” to any other term. “’Biracial’ could be any old thing. Korean and Panamanian or Chinese and Egyptian. But a mulatto is always specifically a mulatto.”) When this sprawling tome is spurned by publishers, Jane decides she’s been wasting her energies on literature and, as was the case with generations of writers before her, dives into the gauzy maelstrom of Hollywood screenwriting, specifically by finding space at a writers’ table developing a TV “prestige” sitcom about the “mulatto” experience. The narrative twists, however clever and trenchant, aren’t what keep your head in the game; it’s the streams of zingers, aphorisms, and socio-cultural observations, whether its Jane’s withering assessment of her students’ reading tastes to the mores of hosting her daughter’s birthday party among the L.A. hoi polloi. As a bonus, Senna’s book also serves as a guide not just to navigating one’s way through a multi-culti life, but to writing itself. And, for that matter, teaching writing. (“You couldn’t teach a student by assigning Toni Morrison, it would only create bad imitations.”) Laugh, and learn.

Sally Jenkins – So many of my friends dropped their Washington Post subscriptions after Jeff Bezos’s non-endorsement for president. While understanding the impulse, I insisted that, however exasperating the Post’s direction on this and other matters, there were still people working there who needed and merited our abiding support. Without the Post, for instance, you’d deprive yourself of beholding a great American sportswriter in the midst of a ferocious hot streak. Jenkins has over decades sustained a level of performance as awe-inspiring as any of the superstar athletes she writes about, whether she’s unspooling long-form pieces like the panoramic, vividly rendered account of legendary bull rider J.B. Mauney’s decelerated-but-still-engaged life after a broken neck or firing column after column taking dead solid aim at Received Wisdom wherever it’s stinking up the joint. She places the blame for the hot mess college athletics have become on the institutions that forget or ignore their educational missions. She was laser-like in deconstructing police overreaction to a pregame traffic infraction by Miami Dolphins receiver Tyreek Hill (“…a needless escalation not because of Hill’s conduct, but that of those chesty cops, their belts jingling with tools of submission and voices that demanded bootlicks…”). While the Tom Brady roast delighted millions, Jenkins was decidedly not amused by the “hammy punchlines that fell like refrigerators hitting sidewalks.” And she was, as usual, smarter than almost everybody else in her field when assessing Bill Belichick’s decision to forsake the klieg-light glare of the NFL for the NCAA: “Belichick’s longtime permafrost barrier is less about aloofness than about his suspicion of the corrosive effects of popularity.” Jenkins has been a perennial finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, and I thought her engrossing, deeply moving 2023 takeout on the bond between Chris Evert-Martina Navratilova should have finally put her over the top. Then again, she doesn’t need anybody’s prizes to certify her preeminence – not as much as you need to pay more attention to her day-to-day output.

Beyonce, Cowboy Carter (Parkwood/Columbia) – So who needs the CMA anyway? Those are for country-&-western albums, and this was the kind of pure pop product that took in too many multitudes to be contained by any genre. More than anything, as many others pointed out, Beyonce herself was, and is, her own genre. And whatever this album’s head-swiveling popularity and impact on the marketplace and its multiple platforms, I don’t think enough was made of Ms. Knowles’s valiant determination to declare that she, too, sings America – as if the opening track, “American Requiem” didn’t forcefully assert such intention. Nothing about this Mother of All Crossover Projects felt strained or overstuffed – except, maybe, for the Texas radio station motif that almost wore out its welcome. Overall, it’s a cordial, enthusiastic house party with an eclectic guest list (Miley Cyrus, Shaboozey, Stevie Wonder, Paul McCartney, Tanner Adell, Rhiannon Giddens, Willie Nelson, Jon Baptiste, Linda Martell, among others) and a generosity of spirit that makes the album’s nay-sayers seem even pettier — and more bewildering. The election results have too many convinced that the country’s regressing deeper into the swamps of polarization. But I think Cowboy Carter’s arrival is the clearest indication we have this year that the wider, more diverse world the reactionaries are so afraid of has already arrived – and isn’t going anywhere anytime soon.

Hacks – Somehow you knew that the perverse bond between Vegas standup comedy institution Deborah Vance (Jean Smart) and her on-and-off-again muse-for-hire Ava Daniels (Hannah Einbinder) was going to need more than just two seasons to evolve. And the third and best season of this series raised the stakes in bringing this oddest of odd couples back together after Deborah cut Ava loose (supposedly) for the latter’s own sake. And it seems, for a time, to have worked out, with Deborah riding a wave of popularity with newer younger audiences who’ve seen her unexpected Netflix hit and Ava scoring a dream gig writing for a satiric news digest. But when the late-night hosting job of Deborah’s long-deferred dreams suddenly becomes attainable, she decides that only Ava’s writing can deliver her to the finish line. So, for better and worse, they reconnect with their respective insecurities and unruly yearnings entwined once again in a fitful tango of codependence and ambition. The sometimes-sordid things they do along the way to get what they want smacks around our sympathies. But there are too damn many things in the culture that pander to simplistic good/evil dualities. Ava’s moments of insight and compassion may not always arrive in a timely manner, but when they do, you wish you could hire her for some odd jobs around the office. And it’s hard to stay mad at Deborah when she makes this rationale for her heat-seeking campaign: “Anything I want to do I have to do it now. Or else I’ll never do it. That’s the worst part about getting older.” No pathos here. Just another shot of raw, aching truth that’ll keep us coming back to these fascinating, damaged women.

Rebel Ridge – I started watching this on Netflix after several people I trust urged me to do so. When it began with an innocent, unarmed Black man on a bicycle getting rousted and harassed by small-town white men in uniform, I thought: Do I really need to go through this mess again (especially this year, or this decade?) But it didn’t take long for Jeremy Saulnier’s contemporary western to pull me all the way in. Which says a lot, given how totally done I’ve become with this kind of drama (especially in real life). The movie is not only smart about orchestrating its martial arts sequences and chase montages, but also about the jujitsu of legal procedure and the pressure points that won’t always, or easily, submit to the bully-bro tactics of overentitled cops. One more thing: Aaron Pierre, as the unstoppable marine vet kicking ass for justice, is a bona fide star and I hope the Green Lantern franchise, such as it is, treats him much better than it did Ryan Reynolds.

The Paris Olympics – They had me, literally, at hello with Celine Dion’s spectral performance of “Hymne a L’Amour” climaxing a moist, stirring opening ceremony. Dion’s spellbinding resolve was sustained in the steely “I’m Baaack!” sang-froid of Simone Biles throughout the women’s gymnastics competition, whether dispatching the competition or supporting her teammates. The men’s basketball competition honored the elder generation of superstars like LeBron James and Stephan Curry while also acting as a showcase for NextGen stars like France’s Victor Wembanyana and Japan’s Kawamura Yuki. Much was made of Katey Ledecky’s four-pack of swimming medals, and even more was made by the pool of local hero “King” (or is it “Roi”?) Leon Marchand. But as always, I was especially riveted to track-and-field, especially the American women sprinters. If there’s one YouTube clip that I never get tired of watching from the games, it’s of Sha ‘Carri Richardson’s come-from-behind anchor leg of the 4X100-meter relay. That millisecond before she breaks the tape is the best victory glance at the competition since Secretariat’s jockey Ron Turcotte sneaked an over-the-shoulder look at how far ahead they were in the 1973 Belmont Stakes.

Desi Lydic – The big story with The Daily Show this year was Jon Stewart’s return to the anchor desk, albeit in a more limited role. With characteristic generosity, Stewart’s still ceding lots of space to the show’s rotating anchors who have been doing just fine without him. They’re all great, but I think Lydic, who joined the franchise back in 2015, has become one of its stealth weapons. And it’s not just because she had the season’s single best zinger, aimed in Tucker Carlson’s direction the day he was dismissed from Fox News. I’m thinking of a relatively routine night for the show, when she surgically took apart what was supposed to be a major policy address by the once-and-future-president on health care and laid out its sloppy, threadbare components for all to see and hear. I turned on the radio and television the morning after waiting for somebody, anybody else to apply even a little of Lydic’s scorched-earth skepticism and deconstruction to this speech. Crickets. At least, that’s all I’d heard. This, by default, made her my favorite broadcast journalist of the 2024 campaign with no one else even close. I’m not expecting the next couple years (at least) to be fun. But I’m at least encouraged that Lydic will still be ready to apply the scythe and flares to Trump’s foggier rhetoric — if “rhetoric” is what you can call it.

The Sympathizer – The culture-at-large is in love with international intrigue to a degree that it hasn’t been since the mid-20th century days of Counterinsurgency, Sean Connery’s 007, and Mutually Assured Destruction. A partial, up-to-date list of global duplicity to be found on streams includes Black Doves, The Agency, Day of the Jackal, The Diplomat, Lioness, and Slow Horses, the latter of which I am so devoted to that I inhale the Mick Herron novels so I can stay out in front of whatever happens to its motley crew of misfits after each of the series’ four seasons. But even that show hasn’t messed with my head like the HBO adaptation of Viet Thanh Nguyen’s award-winning novel, set during and after the Vietnam War, about the perilous destiny of a double agent (a most excellent Hoa Xuande) spying for the communist North while serving as an officer with the South’s army. The novel claims both Ralph Ellison and John Le Carré as its guiding spirits and the series is more faithful to Nguyen’s dark seriocomic narrative than the agent, known only as The Captain, is to either of his warring masters. He carries his divided soul with him after the Fall of Saigon to late-1970s Los Angeles where the war goes on among his fellow refugees, notably his onetime general (Toan Le), now a liquor-store owner still dreaming of somehow reversing the war’s outcome. Robert Downey Jr., one of the show’s executive producers, plays (riotously) multiple roles as white men with undue, malign influence on The Captain’s life, including a sybaritic CIA cowboy, a doltish California congressman, and a megalomaniacal filmmaker using the Captain for technical advice on a Vietnam War epic. Some viewers complained about the story’s multiple time-shifts and how the narrative didn’t always play fair with the Captain’s motivations – and everybody else’s. All of which, of course, was what I liked most about it.

When The Clock Broke –John Ganz’s account of the 1992 presidential campaign was published three days before Joe Biden announced his withdrawal from the presidential race and declared support for his vice president Kamala Harris. The convergence now seems like ages ago, especially when one remembers how suddenly plausible it seemed at that moment that the election results would signal the end — or at least the beginning of the end – of the dismal era that Ganz contends was set in motion by the tempest of reactionary resentment and populist rage abetted by such luminaries of the era as Ross Perot, Pat Buchanan, David Duke, Daryl Gates, Rudy Giuliani, Rush Limbaugh, and others. So omnipresent was this force that even the election’s eventual winner Bill Clinton pandered to it by hanging Black rapper-activist Sister Souljah out to dry in public. Ganz’s mordant, thorough account spares no one in complicity and even brings in John “The Dapper Don” Gotti as a tabloid paradigm of the mob capo as authoritarian ideal. As I wrote this past summer, you’ll find just about everything there is to say about how we ended up in this perilous time for our democratic republic; everything, that is, except a clearly marked exit.

Zoe Saldana – As more than one of my friends insist, there’s nobody better than Saldana at evoking the state of being sick-and-tired-of-everybody-else’s-bullshit, especially when, as the CIA commando in Lioness known as Joe McNamara, she has to be Tough Mommy to her daughters in split-level Virginia and to the grimy, smart-alecky roughnecks she leads into morally ambiguous dark-ops missions. Her character in Emilia Perez is scarcely under less pressure than Joe; she’s a Mexico City lawyer recruited by a notorious drug cartel leader to help navigate his safe passage to a new life as a woman. In both cases, Saldana is a flash point, barely keeping rage and hysteria at bay. She not always at the center of things, but nothing consequential happens, good or bad, without her. While I yearn for the cooler, drier archetype of existential heroism I grew up with, Saldana’s mercurial, intense variation somehow feels closer to where our heads should be now: doing whatever it takes to get through whatever perils get dumped in our pathway

OK, so once and for all, what is an album anyway? If most of the people I know who are 35-and-under are asked this question, they’ll likely answer the way I did way back in 1972: it’s a long-playing vinyl recording, wrapped in plastic and sometimes packaged in pairs, depending on the content. It’s an artifact played on turntables and will never let you down as long as you keep your needles up to snuff. Did you know that cactus needles are just as good, if not better than those diamond needles that were big with stereophiles back in the day? I heard this from my dad, who in turn heard it from this guy in Hartford named Ivor Hugh, a really savvy music aficionado who once played Flippy the Clown on local TV and…I digress again, sorry.

But, seriously, folks, help a brother out: What am I talking about when I talk about “albums,” top ten or otherwise? I still get compact discs from record companies Whatever they are anyway! Can’t give the used ones away anymore! But I still don’t believe anybody who says they’re over and done. That’s what they said about vinyl, and I’ve never forgiven whoever “they” are for making me sell off and otherwise give up on all those records I bought in bulk back in the 80s at Third Street Jazz in Philadelphia.

Otherwise, how does music get around and about? YouTube and Spotify can’t be the only analogues for the 78-RPMs sold at food stores and five-and-dimes over a century ago. Streams, clouds, and other water-based delivery systems are all anybody talks about because they carry the ephemeral authenticity of The New and The Now. But so much of musical content is tied to fashion, which means whatever passes for “sexy” these days. And jazz, whatever that is, isn’t a fashion statement so much now, except for those of us who keep faith with its promises to make sounds fit together and come apart in ways we haven’t heard before.

Somehow, even with all the tumult, volatility, and anxiety of the year now staggering to a close, that faith abides with those of us who get the sounds we want in any delivery system we can use. Is it “fashionable”? Paraphrasing a rhetorical question Max Roach asked me when this subject came up, is being human still “fashionable”?

I wonder sometimes.

Anyway…

1.) Charles Lloyd, The Sky Will Still Be There Tomorrow (Blue Note)—It was released at the start of the year, so who would have dared predict that so many of us would appropriate variations of its title for reassurance by year’s end? Or that its elegiac, melancholy ambiance likewise synched with those who believed things would turn out differently this past November? Current events aside, this four-album (or-two-disc) set feels like a valedictory for the 86-year-old Lloyd, who otherwise doesn’t sound anywhere close to calling time on his long, mercurial career. The plaintive lyricism that has distinguished his playing on both tenor saxophone and flute over the last couple decades is given its fullest, most expansive platform yet for roaming, probing, and exalting, whether paying tribute to the album’s guiding spirit Billie Holiday (“The Ghost of Lady Day”) or taking us to church, as it were, on “Balm in Gilead” and “Lift Every Voice and Sing”. The whole project is both a balm and an exhortation not just to move but contemplate each step forward. What Lloyd describes as this “offering of tenderness” is seasoned with a wistful sense of play and mischief, as on the title track and “Monk’s Dance.” Pianist Jason Moran, longtime supporter and co-conspirator in Lloyd’s spiritual insurgency, joins bassist Larry Grenadier and drummer Brian Blade in helping Lloyd render his offering to the spirits and to us. The package feels right on time – and somehow beyond time. It’ll be around whenever we need it, as, I suspect, its leader will for a while longer.

2.) David Murray Quartet, Francesca (Intakt) – For much of the latter third of the 20th century, Murray was so prolific as a recording artist on bass clarinet and tenor saxophone that he seemed too hyperactive to so much as take a breath between gigs. He’s performed epochal solo recitals, engaged in spiky duets, and led small combos and big bands alike with fearsome power and relentless invention. Murray, a few months shy of 70, still packs a deep, wooly, and enveloping vibrato that, by itself, seems a living organism with throbbing membranes and raw nerves. Yet of the many units Murray’s played with, I can’t recall one that more effectively channels and contains his formidable expressive range than this confab of pianist Marta Sanchez, bassist Luke Stewart, and drummer Russell Carter. From the evidence provided by this album, Murray enjoys being in their company and they each respond in kind to even his most vertiginous playing with intuition and empathy. Carter is air-tight and precise whether laying down a shimmering groove on “Ninno” (an affectionate homage, if you can believe it, to a life-support dog) or merrily shifting tempos on “Cycles and Seasons.” Sanchez and Stewart are gifted composers, possessing what veteran players like to call “Very Big Ears,” especially for finding ways to catch and release harmonic flow, as on “Free Mingus” where Stewart’s darting and dancing bass lines create a center of gravity for both Sanchez and Murray to unfurl their very different, yet complementary approaches to lyricism. If this is what Murray’s eminence gris period will be like, we’re in for more and better surprises like this.

3.) Patricia Brennan Septet, Breaking Stretch (Pyroclastic) –This one should be issued with weather advisories. Any one of these tracks is liable to toss unwary listeners into storm systems of polyrhythmic density capable of lifting them off the floor and onto the ceiling, dancing, of course. Which assumes the roof doesn’t get blown off before they get there. Do I overstate? You’re obliged to find out for yourself. Brennan, a mallet-wielding wonder from Veracruz, Mexico, has made a priority of building her own perfect rhythm machine with her marimba and vibes at its hot core. She appears to have realized this noble endeavor with saxophonists Mark Shim and Jon Irabagon, trumpeter Adam O’Farrill, drummer Marcus Gilmore, percussionist Mauricio Herrera and bassist Kim Cass. Listening to them on full interlock as they roar and rip through “Los Otros Yo (The Other Selves),” “Palo de Oros (Suit of Coins)”or “Manufacturers Trust Company Building” (no, really, that’s the title) applies a stone-cold high to anyone’s bottom-feeding spirit. Even when the group seems to break its air-tight formation — as on, of course, the title track — the soloists have their own afterburners with fuel to spare at any speed. This feels like an evolutionary step for large ensemble jazz, but its forward momentum is of such dimension and lift that I can’t tell for sure where it’ll end up. With any luck, it won’t end at all.

4.) Tyshawn Sorey Trio, The Susceptible Now (PI) – In a year dominated by outstanding piano trio albums, this ensemble led by the Pulitzer Prize-winning percussionist-composer-educator still sets the pace for other such combos with an austere, simple-but-spacious approach to the format. Sorey steers pianist Aaron Diehl and bassist Harish Raghavan with a supple touch that takes them, and us, longer and deeper, the way a submarine helmsman guides his massive ship around the hemisphere and back. McCoy Tyner’s “Peresina” is reconfigured by Sorey’s arrangement into a three-part suite of rhythmic give-and-take while “A Chair in the Sky” takes to heart the lyrics Joni Mitchell wrote to Charles Mingus’ melody (and life) and here becomes an immersive meditation on mortality with a rangy, brightly burning solo from Raghavan woven into its center. The trio’s maximalist-minimalist tension makes a persuasive case for Daniel Gunnarsson’s rakish soul-pop ballad, “Your Good Lies,” as entrancing lounge jazz with Diehl loosening some of his craftier changes over Sorey’s subtly diverse array of grooves. Brad Mehldau’s “Bealtine” keeps some of its original energy, but Team Sorey once again kneads, stretches, and coaxes the tune into broader, more contemplative regions with each solo coming across as its own autonomous composition.

5.) Immanuel Wilkins, Blues Blood (Blue Note)— Its title comes through a 60-year wormhole from a Black Harlem teenager who was one of six arrested and convicted of two April,1964 crimes, one of them the fatal stabbing of a white owner of a used-clothing store. The boy, Daniel Hamm, testified how he and the other five were beaten by police officers while awaiting trial, recounting: “I had to, like, open up the bruise and let some of the blues…bruise blood to come out to how them.” From the “Harlem Six” case, Wilkins, a prodigiously gifted alto playert and producer Meshell Ndegeocello fashion a concept album that’s also a vision of time as a flat circle, melding past, present, and (potential) future of Black America. Along with members of Wilkins’s quartet (pianist Micah Thomas, bassist Rick Rosato, drummer Kweku Sumbry), vocalists June McDoom, Cecile McLoren Salvant, Yaw Agyeman, and Ganavya invoke, incant, and insinuate varied shades of loss and yearning. It may overreach at times on the special effects, the titles alone are triggers for fever dreams: “Matte Glaze,” “Apparition,” “Afterlife Residence Time,” the latter of which oozes into “Moshpit” and in turn leads to the title track, whose hard-driving, time-bending exuberance crack open a doorway to something resembling, if not hope exactly, then resolution, or clarity. For the time being, we’ll have to settle for either.

6.) Samara Joy, Portrait (Verve)— Having won awards and acclaim for both following and enhancing the jazz vocal tradition, Joy could have played things relatively safe by serving up piping-hot renditions of familiar and not-so-familiar standards, summoning memories of Ella, Sarah, and (even) Dinah. This one’s got the familiar and unfamiliar stuff, but with stunning twists and head-swiveling departures from everybody’s expectations. She announces her intentions by not only choosing Mingus’s Charlie Parker homage, “Reincarnation of a Lovebird,” but writing her own lyrics. And then there’s her breathtaking rendition itself, starting with an a cappella chorus whose acrobatic displays of melisma hint at the powerful fireworks to come, especially at the rousing finish. She maintains this dizzyingly high altitude at slower tempi on “Autumn Nocturne” and Barry Harris’s “Now and Then (In Remembrance Of…) for which she also wrote lyrics. She takes her biggest swing with a mélange of her own “Peace of Mind” with Sun Ra’s “Dreams Come True,” which comes across as both an anthem of personal uplift and an expression of her own artistic doctrine up to now. When I hear an album like “Portrait,” I don’t just think of Sarah or Ella or (even) Dinah or Billie. I’m thinking of somebody Brenda Lee, belting her heart out for all its worth, whether in Nashville or London, because she’s got the means, the pipes, and the eternal promise that makes everybody’s heart swell up when beholding someone willing and able to bust one, high and hard, far out of the park.

7.) Kris Davis Trio, Run The Gauntlet (Pyroclastic) – For this first album with her new trio mates, drummer Jonathan Blake and bassist Robert Hurst, Davis is honoring six women pianists – Geri Allen, Carla Bley, Marilyn Crispell, Angelica Sanchez, Sylvie Courvoisier, and Renee Roses – whom the Canadian-born Grammy winner extols as “beacons of possibility during different stages of my development, showing me that a career in music – whether as a woman, an immigrant, a parent, or a fan of avant-garde music – was attainable.” The title track follows imperatives set down by her influences with an invigorating progression of riffs and vamps marching, weaving, sometimes ducking and diving towards what you think will be resolution, but instead unleashes more challenging inventions and knottier themes. Her inquisitive creativity as a leader and soloist pervades the rest of the album’s selections, whether on the intense, bottom-heavy “Knotweed,” where her interaction with Hurst and Blake is at its most proficient, the limpid, enigmatic patterns realized in the trio’s rendering of Blake’s “Beauty Beneath the Rubble Meditation” and the pure exaltation given shape and form by the trio on “Heavy Footed.” You don’t hear too many direct references to the women Davis cites in the music and you don’t need to. They’re where they should be: in everything she’s putting down and laying out.

8.) Matthew Shipp Trio, New Concepts in Piano Trio Jazz (ESP-Disk) – Shipp has never showed an inclination towards tribute albums. Yet the “New Concepts” assembled here comprise a kind of homage to the late Ahmad Jamal in the manner of breaking down piano-jazz trio performance to its basic elements. Shipp, known for assembling tone clusters into skyscraping mosaics at the keyboard, plays with more spareness than usual. Nevertheless, the choices he makes in his thematic attacks are as revealing of his insurgent sensibility as any of his more sprawling solos, even though “Brain Work,” his one solo track here, is as quirkily laconic as anything he plays with the others. Bassist Michael Bisio and drummer Nicholas Taylor Baker have worked with Shipp for over a decade and their comfort level with each other is such that it takes just a few interlocking phrases from each to detonate “The Function,” whose loping pulse and recombinant harmonies forge a kind of astral boogie-woogie for the 21st century. As quirky and willfully abstract as ever, Shipp and his men here present what could be the most accessible gateway to the Wilmington Whirlwind’s body-of-work, alone or with others.

9.) Allen Lowe & the Constant Sorrow Orchestra, Louis Armstrong’s America, Vols. 1 & 2 (ESP) – If you know Lowe, you know better than to expect a Louis Armstrong homage that dutifully trots out the classic Pops songbook and does whatever it can to replicate the great man’s music. Instead, this four-disc set, at once gnomic and epochal, typifying whatever one means by, or expects from the “Allen Lowe Experience,” is more intent on evoking the anarchic spirit of invention that propelled Armstrong’s innovations of a century ago. As with the greatest American inventors, Armstrong used whatever was close at hand to construct his voice as player, singer, and performer and this project carries that same freewheeling, go-for-broke spirit in its tossed salad of gutbucket blues, neo-bop, amplified rock, even a little backwoods swing. It is also worth mentioning here that Lowe, who has faced daunting health challenges over the last several years, plays his tenor sax with greater energy and freer-flowing lyricism. He brings along his customary large and eclectic supporting cast that includes pianists Lewis Porter, Matthew Shipp, and Loren Schoenberg, trumpeter Frank Lacy, guitarist Marc Ribot, trombonist Ray Anderson and banjoist Ray Suhy (who could be the album’s equivalent of the Energizer Bunny, if the leader’s indefatigable performance weren’t as inexorable throughout.) And as ever, there’s the textual stuff, the liner notes that explain why he came up with tunes and titles like “Aaron Copland Has the Blues,” “Lester Lopes In,” “Joi Lansing Escapes from the Web of Love,” “In Dreams Begin Isaac Rosenfeld,” and “Beefhart’s on Parade,” the latter of which is a play on Pops’ “Sweethearts on Parade,” though, as you can already surmise, the former has little to do with the latter beyond the same chord changes. Except, maybe, in the old-time modernist impulse to Make It New – and, if plausible, Make It Swing.

10.) Christian McBride & Edgar Meyer, But Who’s Gonna Play the Melody? (Mack Avenue) – Maybe it’s my age, but I’m finding that lately, whether live or on record, a fresh slice of music is as likely to grab my attention with its bass line than whatever the front-line players are doing. (Genetics. Same thing happened eventually with my dad.) Still, the idea of double-bass players occupying the core of a whole album seemed a bridge too far (or a gimmick too blatant). And so, it took some time for me to suss out the savory charms of this unusual summit meeting. It’d be too easy to declare at the outset that McBride brings out the blues swinger in Meyer and that Meyer conversely brings out the eclectic classicist in McBride because the more you listen to the whole album, the harder it is to discern any difference between them. After McBride counts off at the start of his “Philly Slop,” you presume that Meyer is merrily juking and slipping through the brick-solid 4/4 beat McBride is laying down. Or is it the other way around? It doesn’t matter. The whole point of this colloquy is to blur any distinctions between the Philadelphia-bred R&B kid who grew into jazz music’s most recognizable bass master and the gentleman from Tennessee who can pivot on a dime from the classical repertoire to a bluegrass jam. They both acquit themselves with distinction tearing through Miles Davis’s “Solar” at high velocity just as they do on Bill Monroe’s “Tennessee Blues.” Who’s playing what? In America, they can play whatever they want, however they want, in however big a space they can get. That’s the whole point of this album – and should be the whole point of everything else.

HONORABLE MENTION

Luke Stewart Silt Trio (PI), Kenny Barron, Beyond This Place (Artwork), Vijay Iyer, Compassion (ECM), Marta Sanchez Trio, Perpetual Void (Intakt), Steve Coleman and Five Elements, PolyTropos/Of Many Turns (PI), Abdullah Ibrahim, Three (Gearbox)

ARCHIVAL

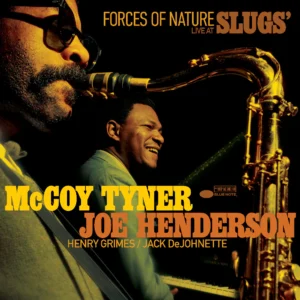

1. )McCoy Tyner & Joe Henderson, Forces of Nature: Live at Slugs (Blue Note)

2.) Bobby Hutcherson, Complete Blue Note Sessions, 1963-1970 (Mosaic)

3.) Ron Miles, Old Man Chapel (Blue Note)

4.) Mal Waldron & Steve Lacy, The Mighty Warriors (Elemental)

5.) Yusef Lateef, Atlantis Lullaby: The Concert from Avignon (Elemental)

LATIN

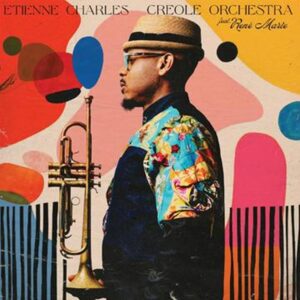

Etienne Charles Creole Orchestra (Culture Shock)

Miguel Zenon, Golden City (Miel Music)

VOCAL

Samara Joy, Portrait (Verve)

Kurt Elling & Sullivan Fortner, Wildflowers Vol. 1 (Edition)

Luciana Souza, Twenty-Four Short Musical Episodes (Sunnyside)