OK, so once and for all, what is an album anyway? If most of the people I know who are 35-and-under are asked this question, they’ll likely answer the way I did way back in 1972: it’s a long-playing vinyl recording, wrapped in plastic and sometimes packaged in pairs, depending on the content. It’s an artifact played on turntables and will never let you down as long as you keep your needles up to snuff. Did you know that cactus needles are just as good, if not better than those diamond needles that were big with stereophiles back in the day? I heard this from my dad, who in turn heard it from this guy in Hartford named Ivor Hugh, a really savvy music aficionado who once played Flippy the Clown on local TV and…I digress again, sorry.

But, seriously, folks, help a brother out: What am I talking about when I talk about “albums,” top ten or otherwise? I still get compact discs from record companies Whatever they are anyway! Can’t give the used ones away anymore! But I still don’t believe anybody who says they’re over and done. That’s what they said about vinyl, and I’ve never forgiven whoever “they” are for making me sell off and otherwise give up on all those records I bought in bulk back in the 80s at Third Street Jazz in Philadelphia.

Otherwise, how does music get around and about? YouTube and Spotify can’t be the only analogues for the 78-RPMs sold at food stores and five-and-dimes over a century ago. Streams, clouds, and other water-based delivery systems are all anybody talks about because they carry the ephemeral authenticity of The New and The Now. But so much of musical content is tied to fashion, which means whatever passes for “sexy” these days. And jazz, whatever that is, isn’t a fashion statement so much now, except for those of us who keep faith with its promises to make sounds fit together and come apart in ways we haven’t heard before.

Somehow, even with all the tumult, volatility, and anxiety of the year now staggering to a close, that faith abides with those of us who get the sounds we want in any delivery system we can use. Is it “fashionable”? Paraphrasing a rhetorical question Max Roach asked me when this subject came up, is being human still “fashionable”?

I wonder sometimes.

Anyway…

1.) Charles Lloyd, The Sky Will Still Be There Tomorrow (Blue Note)—It was released at the start of the year, so who would have dared predict that so many of us would appropriate variations of its title for reassurance by year’s end? Or that its elegiac, melancholy ambiance likewise synched with those who believed things would turn out differently this past November? Current events aside, this four-album (or-two-disc) set feels like a valedictory for the 86-year-old Lloyd, who otherwise doesn’t sound anywhere close to calling time on his long, mercurial career. The plaintive lyricism that has distinguished his playing on both tenor saxophone and flute over the last couple decades is given its fullest, most expansive platform yet for roaming, probing, and exalting, whether paying tribute to the album’s guiding spirit Billie Holiday (“The Ghost of Lady Day”) or taking us to church, as it were, on “Balm in Gilead” and “Lift Every Voice and Sing”. The whole project is both a balm and an exhortation not just to move but contemplate each step forward. What Lloyd describes as this “offering of tenderness” is seasoned with a wistful sense of play and mischief, as on the title track and “Monk’s Dance.” Pianist Jason Moran, longtime supporter and co-conspirator in Lloyd’s spiritual insurgency, joins bassist Larry Grenadier and drummer Brian Blade in helping Lloyd render his offering to the spirits and to us. The package feels right on time – and somehow beyond time. It’ll be around whenever we need it, as, I suspect, its leader will for a while longer.

2.) David Murray Quartet, Francesca (Intakt) – For much of the latter third of the 20th century, Murray was so prolific as a recording artist on bass clarinet and tenor saxophone that he seemed too hyperactive to so much as take a breath between gigs. He’s performed epochal solo recitals, engaged in spiky duets, and led small combos and big bands alike with fearsome power and relentless invention. Murray, a few months shy of 70, still packs a deep, wooly, and enveloping vibrato that, by itself, seems a living organism with throbbing membranes and raw nerves. Yet of the many units Murray’s played with, I can’t recall one that more effectively channels and contains his formidable expressive range than this confab of pianist Marta Sanchez, bassist Luke Stewart, and drummer Russell Carter. From the evidence provided by this album, Murray enjoys being in their company and they each respond in kind to even his most vertiginous playing with intuition and empathy. Carter is air-tight and precise whether laying down a shimmering groove on “Ninno” (an affectionate homage, if you can believe it, to a life-support dog) or merrily shifting tempos on “Cycles and Seasons.” Sanchez and Stewart are gifted composers, possessing what veteran players like to call “Very Big Ears,” especially for finding ways to catch and release harmonic flow, as on “Free Mingus” where Stewart’s darting and dancing bass lines create a center of gravity for both Sanchez and Murray to unfurl their very different, yet complementary approaches to lyricism. If this is what Murray’s eminence gris period will be like, we’re in for more and better surprises like this.

3.) Patricia Brennan Septet, Breaking Stretch (Pyroclastic) –This one should be issued with weather advisories. Any one of these tracks is liable to toss unwary listeners into storm systems of polyrhythmic density capable of lifting them off the floor and onto the ceiling, dancing, of course. Which assumes the roof doesn’t get blown off before they get there. Do I overstate? You’re obliged to find out for yourself. Brennan, a mallet-wielding wonder from Veracruz, Mexico, has made a priority of building her own perfect rhythm machine with her marimba and vibes at its hot core. She appears to have realized this noble endeavor with saxophonists Mark Shim and Jon Irabagon, trumpeter Adam O’Farrill, drummer Marcus Gilmore, percussionist Mauricio Herrera and bassist Kim Cass. Listening to them on full interlock as they roar and rip through “Los Otros Yo (The Other Selves),” “Palo de Oros (Suit of Coins)”or “Manufacturers Trust Company Building” (no, really, that’s the title) applies a stone-cold high to anyone’s bottom-feeding spirit. Even when the group seems to break its air-tight formation — as on, of course, the title track — the soloists have their own afterburners with fuel to spare at any speed. This feels like an evolutionary step for large ensemble jazz, but its forward momentum is of such dimension and lift that I can’t tell for sure where it’ll end up. With any luck, it won’t end at all.

4.) Tyshawn Sorey Trio, The Susceptible Now (PI) – In a year dominated by outstanding piano trio albums, this ensemble led by the Pulitzer Prize-winning percussionist-composer-educator still sets the pace for other such combos with an austere, simple-but-spacious approach to the format. Sorey steers pianist Aaron Diehl and bassist Harish Raghavan with a supple touch that takes them, and us, longer and deeper, the way a submarine helmsman guides his massive ship around the hemisphere and back. McCoy Tyner’s “Peresina” is reconfigured by Sorey’s arrangement into a three-part suite of rhythmic give-and-take while “A Chair in the Sky” takes to heart the lyrics Joni Mitchell wrote to Charles Mingus’ melody (and life) and here becomes an immersive meditation on mortality with a rangy, brightly burning solo from Raghavan woven into its center. The trio’s maximalist-minimalist tension makes a persuasive case for Daniel Gunnarsson’s rakish soul-pop ballad, “Your Good Lies,” as entrancing lounge jazz with Diehl loosening some of his craftier changes over Sorey’s subtly diverse array of grooves. Brad Mehldau’s “Bealtine” keeps some of its original energy, but Team Sorey once again kneads, stretches, and coaxes the tune into broader, more contemplative regions with each solo coming across as its own autonomous composition.

5.) Immanuel Wilkins, Blues Blood (Blue Note)— Its title comes through a 60-year wormhole from a Black Harlem teenager who was one of six arrested and convicted of two April,1964 crimes, one of them the fatal stabbing of a white owner of a used-clothing store. The boy, Daniel Hamm, testified how he and the other five were beaten by police officers while awaiting trial, recounting: “I had to, like, open up the bruise and let some of the blues…bruise blood to come out to how them.” From the “Harlem Six” case, Wilkins, a prodigiously gifted alto playert and producer Meshell Ndegeocello fashion a concept album that’s also a vision of time as a flat circle, melding past, present, and (potential) future of Black America. Along with members of Wilkins’s quartet (pianist Micah Thomas, bassist Rick Rosato, drummer Kweku Sumbry), vocalists June McDoom, Cecile McLoren Salvant, Yaw Agyeman, and Ganavya invoke, incant, and insinuate varied shades of loss and yearning. It may overreach at times on the special effects, the titles alone are triggers for fever dreams: “Matte Glaze,” “Apparition,” “Afterlife Residence Time,” the latter of which oozes into “Moshpit” and in turn leads to the title track, whose hard-driving, time-bending exuberance crack open a doorway to something resembling, if not hope exactly, then resolution, or clarity. For the time being, we’ll have to settle for either.

6.) Samara Joy, Portrait (Verve)— Having won awards and acclaim for both following and enhancing the jazz vocal tradition, Joy could have played things relatively safe by serving up piping-hot renditions of familiar and not-so-familiar standards, summoning memories of Ella, Sarah, and (even) Dinah. This one’s got the familiar and unfamiliar stuff, but with stunning twists and head-swiveling departures from everybody’s expectations. She announces her intentions by not only choosing Mingus’s Charlie Parker homage, “Reincarnation of a Lovebird,” but writing her own lyrics. And then there’s her breathtaking rendition itself, starting with an a cappella chorus whose acrobatic displays of melisma hint at the powerful fireworks to come, especially at the rousing finish. She maintains this dizzyingly high altitude at slower tempi on “Autumn Nocturne” and Barry Harris’s “Now and Then (In Remembrance Of…) for which she also wrote lyrics. She takes her biggest swing with a mélange of her own “Peace of Mind” with Sun Ra’s “Dreams Come True,” which comes across as both an anthem of personal uplift and an expression of her own artistic doctrine up to now. When I hear an album like “Portrait,” I don’t just think of Sarah or Ella or (even) Dinah or Billie. I’m thinking of somebody Brenda Lee, belting her heart out for all its worth, whether in Nashville or London, because she’s got the means, the pipes, and the eternal promise that makes everybody’s heart swell up when beholding someone willing and able to bust one, high and hard, far out of the park.

7.) Kris Davis Trio, Run The Gauntlet (Pyroclastic) – For this first album with her new trio mates, drummer Jonathan Blake and bassist Robert Hurst, Davis is honoring six women pianists – Geri Allen, Carla Bley, Marilyn Crispell, Angelica Sanchez, Sylvie Courvoisier, and Renee Roses – whom the Canadian-born Grammy winner extols as “beacons of possibility during different stages of my development, showing me that a career in music – whether as a woman, an immigrant, a parent, or a fan of avant-garde music – was attainable.” The title track follows imperatives set down by her influences with an invigorating progression of riffs and vamps marching, weaving, sometimes ducking and diving towards what you think will be resolution, but instead unleashes more challenging inventions and knottier themes. Her inquisitive creativity as a leader and soloist pervades the rest of the album’s selections, whether on the intense, bottom-heavy “Knotweed,” where her interaction with Hurst and Blake is at its most proficient, the limpid, enigmatic patterns realized in the trio’s rendering of Blake’s “Beauty Beneath the Rubble Meditation” and the pure exaltation given shape and form by the trio on “Heavy Footed.” You don’t hear too many direct references to the women Davis cites in the music and you don’t need to. They’re where they should be: in everything she’s putting down and laying out.

8.) Matthew Shipp Trio, New Concepts in Piano Trio Jazz (ESP-Disk) – Shipp has never showed an inclination towards tribute albums. Yet the “New Concepts” assembled here comprise a kind of homage to the late Ahmad Jamal in the manner of breaking down piano-jazz trio performance to its basic elements. Shipp, known for assembling tone clusters into skyscraping mosaics at the keyboard, plays with more spareness than usual. Nevertheless, the choices he makes in his thematic attacks are as revealing of his insurgent sensibility as any of his more sprawling solos, even though “Brain Work,” his one solo track here, is as quirkily laconic as anything he plays with the others. Bassist Michael Bisio and drummer Nicholas Taylor Baker have worked with Shipp for over a decade and their comfort level with each other is such that it takes just a few interlocking phrases from each to detonate “The Function,” whose loping pulse and recombinant harmonies forge a kind of astral boogie-woogie for the 21st century. As quirky and willfully abstract as ever, Shipp and his men here present what could be the most accessible gateway to the Wilmington Whirlwind’s body-of-work, alone or with others.

9.) Allen Lowe & the Constant Sorrow Orchestra, Louis Armstrong’s America, Vols. 1 & 2 (ESP) – If you know Lowe, you know better than to expect a Louis Armstrong homage that dutifully trots out the classic Pops songbook and does whatever it can to replicate the great man’s music. Instead, this four-disc set, at once gnomic and epochal, typifying whatever one means by, or expects from the “Allen Lowe Experience,” is more intent on evoking the anarchic spirit of invention that propelled Armstrong’s innovations of a century ago. As with the greatest American inventors, Armstrong used whatever was close at hand to construct his voice as player, singer, and performer and this project carries that same freewheeling, go-for-broke spirit in its tossed salad of gutbucket blues, neo-bop, amplified rock, even a little backwoods swing. It is also worth mentioning here that Lowe, who has faced daunting health challenges over the last several years, plays his tenor sax with greater energy and freer-flowing lyricism. He brings along his customary large and eclectic supporting cast that includes pianists Lewis Porter, Matthew Shipp, and Loren Schoenberg, trumpeter Frank Lacy, guitarist Marc Ribot, trombonist Ray Anderson and banjoist Ray Suhy (who could be the album’s equivalent of the Energizer Bunny, if the leader’s indefatigable performance weren’t as inexorable throughout.) And as ever, there’s the textual stuff, the liner notes that explain why he came up with tunes and titles like “Aaron Copland Has the Blues,” “Lester Lopes In,” “Joi Lansing Escapes from the Web of Love,” “In Dreams Begin Isaac Rosenfeld,” and “Beefhart’s on Parade,” the latter of which is a play on Pops’ “Sweethearts on Parade,” though, as you can already surmise, the former has little to do with the latter beyond the same chord changes. Except, maybe, in the old-time modernist impulse to Make It New – and, if plausible, Make It Swing.

10.) Christian McBride & Edgar Meyer, But Who’s Gonna Play the Melody? (Mack Avenue) – Maybe it’s my age, but I’m finding that lately, whether live or on record, a fresh slice of music is as likely to grab my attention with its bass line than whatever the front-line players are doing. (Genetics. Same thing happened eventually with my dad.) Still, the idea of double-bass players occupying the core of a whole album seemed a bridge too far (or a gimmick too blatant). And so, it took some time for me to suss out the savory charms of this unusual summit meeting. It’d be too easy to declare at the outset that McBride brings out the blues swinger in Meyer and that Meyer conversely brings out the eclectic classicist in McBride because the more you listen to the whole album, the harder it is to discern any difference between them. After McBride counts off at the start of his “Philly Slop,” you presume that Meyer is merrily juking and slipping through the brick-solid 4/4 beat McBride is laying down. Or is it the other way around? It doesn’t matter. The whole point of this colloquy is to blur any distinctions between the Philadelphia-bred R&B kid who grew into jazz music’s most recognizable bass master and the gentleman from Tennessee who can pivot on a dime from the classical repertoire to a bluegrass jam. They both acquit themselves with distinction tearing through Miles Davis’s “Solar” at high velocity just as they do on Bill Monroe’s “Tennessee Blues.” Who’s playing what? In America, they can play whatever they want, however they want, in however big a space they can get. That’s the whole point of this album – and should be the whole point of everything else.

HONORABLE MENTION

Luke Stewart Silt Trio (PI), Kenny Barron, Beyond This Place (Artwork), Vijay Iyer, Compassion (ECM), Marta Sanchez Trio, Perpetual Void (Intakt), Steve Coleman and Five Elements, PolyTropos/Of Many Turns (PI), Abdullah Ibrahim, Three (Gearbox)

ARCHIVAL

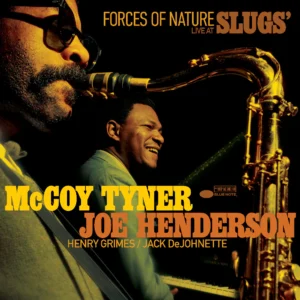

1. )McCoy Tyner & Joe Henderson, Forces of Nature: Live at Slugs (Blue Note)

2.) Bobby Hutcherson, Complete Blue Note Sessions, 1963-1970 (Mosaic)

3.) Ron Miles, Old Man Chapel (Blue Note)

4.) Mal Waldron & Steve Lacy, The Mighty Warriors (Elemental)

5.) Yusef Lateef, Atlantis Lullaby: The Concert from Avignon (Elemental)

LATIN

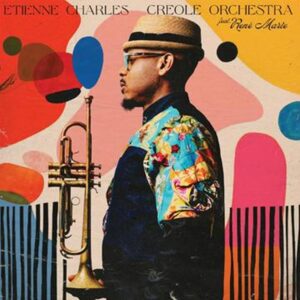

Etienne Charles Creole Orchestra (Culture Shock)

Miguel Zenon, Golden City (Miel Music)

VOCAL

Samara Joy, Portrait (Verve)

Kurt Elling & Sullivan Fortner, Wildflowers Vol. 1 (Edition)

Luciana Souza, Twenty-Four Short Musical Episodes (Sunnyside)