Entries from June 2013 ↓

June 19th, 2013 — jazz reviews

My live-music drought ended last week as I attended a couple of club dates associated with the DC Jazz Festival. I saw Cyrus Chestnut at the Hamilton and couldn’t decide whether I was more astonished at how much better he’s gotten at this piano-trio thing or that he’s now months shy of his 50th birthday. (Watching him be clever, engaging and soulful at the same time makes me think he not only compensates for Mulgrew Miller’s absence, but Dave Brubeck’s, too.) I also made my long-overdue first trip to the Bohemian Caverns on U Street to hear the seemingly unstoppable Pharaoh Sanders lead his secular-spiritual congregation in song. (His tenor doesn’t have a fastball any more, but it can still pull a high, hard one out of thin air when he needs it.)

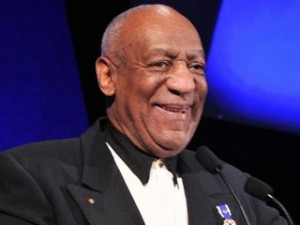

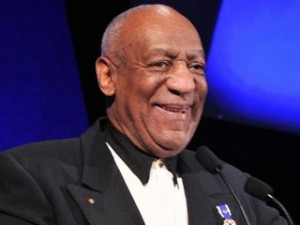

But the best jazz performance I saw this past week wasn’t affiliated with the festival. It was Saturday night at Wolf Trap as Dr. William Henry Cosby Jr. had the Filene Center stage all to himself, sharing it with no one but a pair of sign-language specialists trading off translation duty for the whole two-and-a-half-hours-with-no-intermission-whatsoever show. He spent the whole time talking, just talking…in roughly the same manner that Ben Webster or Pee Wee Russell were just groping for notes on their respective instruments.

Now before I go on…

It’s become a conditioned reflex, especially on the Internet, to acknowledge anything with the words, “Bill Cosby”, as a prelude to (or occasion for) sanctimony or indignation. He has, within the last decade, gone from being an ecumenically beloved entertainer to a polarizing figure, especially within the African American community, whose adults he has challenged or chastised, depending on how you hear him submit his case, to take greater responsibility for their children’s well-being and education. Some believe he speaks the truth that few want to hear while others think he speaks with the haughty arrogance of the wealthy. Then again, even if he hadn’t brought all this up, people will still say he’s haughty and arrogant only because he IS wealthy. Take your pick, brothers and sisters: A passionate “race man” using his power and fame to staunch long-festering socio-cultural wounds with astringent medicine or just another plutocrat playing his own version of that venerable board game, “Blame the Victim.”

I say, with a clear conscience: Whatever. I’ve heard and, at times, even said some of the same things Cosby has about community responsibility — and been resoundingly, unanimously ignored for my trouble. On the other hand, if the Michael Eric Dysons of the world want to rip Cosby a new one, it’s no skin off my ass nose. I don’t have an investment in Bill Cosby the public scourge, philanthropist, educator and TV icon. I am, however, quite weary of the way all these other classifications further diminish or obscure the enduring artistry of a master storyteller adjusting his craft to the pressing demands of age and time.

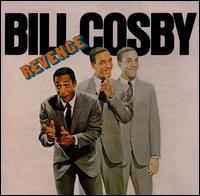

After all, just about everything I’ve ever learned about narrative development didn’t begin with my reading Dickens or Chekhov or even Garcia Marquez. It began with my exposure to Cosby’s LPs of the 1960s. If all you remember of the first “Fat Albert” story from the 1967 LP, Revenge, is that damned “Hey-Hey-Hey!”, then you’re part of this problem. What I remember is that part of the track where Cosby’s recalling the time he tried to get a rise out of Albert by pushing, shoving and jamming him up several flights of stairs leading to a dimly-lit, horror-movie cut-out of a monster. All the while, the younger Cosby’s anticipating the hilarity that will ensue when jovial Albert is frightened out of his wits. The build-up climaxes with the appearance of the scarifying cutout, punctuated by this sound: “AAARRRRAAAUWWGH” (or something to that effect).

Then there’s a pause, not long, but spacious enough to allow Cosby to say, as blankly and blandly as possible: “I forgot I was behind him.” The sentence stands there, suspended in mid-air. Forty-plus years later, I’m still trying to write something as immaculately framed and timed as that.

Watching Cosby work at Wolf Trap (and he’s been touring with most of this material for some time now), I’m aware that, at 75, his build-ups and pay-offs don’t have that same giddyap they did when he was the 28-year-old phenom able to connect his North Philadelphia childhood memories with the world-at-large either through the telling little detail (“idiot mittens”) or the plausibly implausible exaggeration (“Nine-hundred cop cars!”) And yet, paraphrasing his late friend Dizzy Gillespie, Cosby has benefited from a lifetime’s experience in learning what NOT to say and when NOT to say it. So he now uses bigger frames and larger spaces, letting them do more of the work than the words. Most comedians (and musicians) temper their deliveries, slow their rolls as they age without showing any lapses in their command of time and space. And Cosby, a far more formidable rhythm master as a public speaker than as an actual drummer (by his own admission), can make an evening zoom by while seeming to amble along in measured, deliberate steps. How he’s managed to fill amphitheaters with this slow-hand delivery in the digital age is both a major mystery and a minor miracle.

I’d heard the centerpiece story before: An epic ramble about his eldest daughter’s misadventures with higher education – though I suspect he has by now conflated the experiences with other offspring. He braided this version with other, comparably familiar narrative strands. For instance, how a girlfriend, with the emphasis on the last syllable, changes everything, including the balance of domestic power, upon becoming a spouse. (Yes, Camille comes in for yet more ridicule, but something tells me she enables this treatment — up to what point I suppose we’ll never really know.) Then there are the vagaries of being rich and influential. (Upon asking the president of a college to which his daughter seeks admission whether he could use a hospital, the president asks, “And just how bad were those SAT scores, Mr. Cosby?”) He’s gotten cuffed over the last thirty years for leaning on this persona, to which one can only say that he has as much right, even a duty, to mine material from his rich-and-influential life. He was the lovable curmudgeon throughout, yet the evening was generally sanctimony-free – unless you count his rendering of a college graduation in which the top two students of the class, both foreign-born, accepted their diplomas with circumspection and restraint, while the relative underachievers went into ever-more-elaborate variations of the end-zone celebration. Grouchy or not, the displays made their point, each marking one of the precious few times he got up from his chair.

I’ve read elsewhere that 90 minutes is usually his limit. But the fact that he went over his anticipated two-hour time allotment suggests he was enjoying himself. And maybe these concerts are now his down time from being pressed for commentary about families and education. There are worse ways to blow off steam than frolicking with sound the way a painter plays with light. Hardly anyone thinks of Bill Cosby in such aesthetic terms. And it may be partly his fault that more people don’t. But they should.

June 16th, 2013 — movie reviews

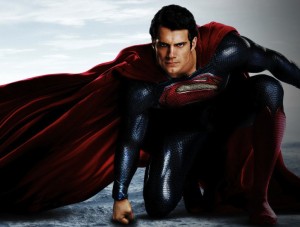

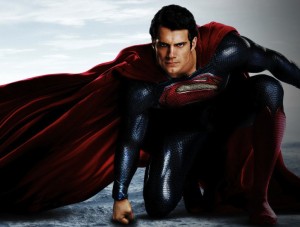

This really shouldn’t have surprised anybody. I’ll go out on a very slender limb and predict that the 71 percent drop for Man of Steel will be even more precipitous over the next few weekends. Summer blockbusters eat each other like the savage carnivores they are and it’s more than probable that by Bastille Day (or, maybe, the Fourth), Clark Kent will join Tony Stark and Mister Spock at the rickety refuse-truck stop on the outskirts of Hype City wondering where the buzz went. The latter two shouldn’t worry too much about coming back. But Superman? He’s in a vulnerable spot. The last time they tried to retrofit him into a new movie franchise, they did it with a movie with an impressive cast, a generally favorable critical consensus (though hardly an overpowering one) and the requisite big-bang set pieces. But for whatever reason, Superman Returns (2006) collected a indecipherable odor that kept it from re-igniting the franchise. In retrospect, Hollywoodland, the neo-noir biopic probing the mysterious death of George Reeves, was the Superman movie that more people talked about that same year. Maybe because it had a better lead actor? You be the judge. I think it may have had something to do with where the world now places its collective memory of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s 75-year-old creation…and whether it believes it can now do without the myth of Krypton’s Last Son.

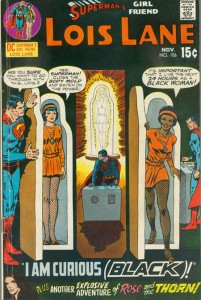

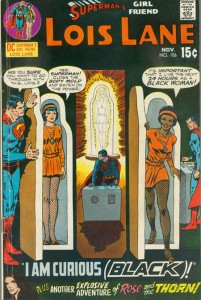

Some of this tangled feeling poked through many of the reviews for Man of Steel (a less impressive consensus this time around, but deceptively so) which moped about Zach Snyder’s reboot having few of the “fun” trappings of Superman’s earlier TV and movie incarnations. These pundits lamented what they saw as the heavy hand of producer Christopher Nolan imposing upon their Superman (whoever that may be) the kind of murky shadows and psychological depth that informed his Dark Knight trilogy’s re-framing of Batman. I found most of these complaints inane and ill-informed. Anybody who grew up reading DC comics at any point in the last 50 or even 60 years knows that there is not now and never has been a life story of Superman that wasn’t subject to revision or tweaking short of making him a refugee from somewhere other than Krypton who landed somewhere other than Kansas.. (Remember all those “what-if” issues of the late 1950s and early 1960s? “What If Lex Luthor Was Superman’s Friend?”, “What If Superman’s Real Parents Came to Earth With Him?” and my all-time favorite, “What If Lois Lane Were Black?” You can look that one up yourself.) For what it’s worth, I always preferred the animated versions of Superman above those with Reeves and even Reeve. Look here and here….and, what the hell, even here.

Ah, yes, that reminds me…Remember the first “teaser” trailers they were showing for Man of Steel, the ones that started running sometime during last summer’s political conventions? They were a gauzy montage of images; a butterfly on a swing, some farmland shrouded in morning fog, a fishing boat with grimy bearded men, a little boy playing with his dog amidst backyard clotheslines with some big red towel or blanket trailing behind him…

At the time, I thought: “Smallville Mon Amour”? I’d be up for that. I figured if Nolan, Snyder and screenwriter David S. Goyer were REALLY serious about dialing everything down to zero and rebuilding the myth from there, they could do a lot worse than take things sideways and make it a more intimate and, thus, more daring species of superhero movie. Sure, you would have bewildered more mass circulation critics, spooked the global distributors and angered the carny rabble. You might even risk flopping worse than, say, Breakfast of Champions or Gigli. Good or bad, you wouldn’t have left anyone indifferent. And what’s more: People would have been talking about your movie beyond opening weekend and (maybe) kept the buzz going all summer long.

As it is, Snyder’s reboot manages to broaden the myth’s expressive possibilities while fulfilling the corporate mandate of blowing things up, literally and figuratively speaking. (More on this later.) Up till now, the romance of being Faster Than…, More Powerful Than…, Able to Leap…, etc. emitted such a powerful hold on our imaginations, at whatever age, that it rarely , if ever, occurred to us to ask what should have been the myth’s most pressing question: How do you adjust to life among other humans if you’re so drastically, even cosmically different from everybody else? A lot of us ran to comic books looking for heroes who were empowered, rather than diminished by being different. What’s best about Man of Steel is its willingness to drink deep from that dilemma. I loved the whole subplot about Clark (and, later, the other Krypton survivors) reeling from the sensory overload caused by being able to see through and hear everything around them. It’s the last thing the lazier savants want to hear: that being super is just another way of being seriously fucked.

There was one moment that chilled me more than anything else in Man of Steel or any other superhero movie in recent memory. It came when Kevin Costner, in his most striking big-screen performance in decades as Jonathan Kent, is reminding his adopted son to resist disclosing his powers, even if they were needed to save his schoolmates from drowning in a waterlogged school bus. “Should I have let them die?” Clark asks. A pause from Pa seems to last forever before he finally mutters, “Maybe.” There’s a web of weary, conflicted emotion enveloping that reply and if the rest of Man of Steel managed to modulate its gaudier impulses in the same manner as Clark struggled to rein in his hearing, it might have been something major, instead of…just big…

…and loud…and messy…I mean I hate being predictable, but count me among the wet blankets who left the theaters grousing about the ringing in their ears and metal shavings in their mouths from all the concussive property damage, the bloodless (and thus, ultimately, numbing) carnage and the multiple rounds of false climaxes that are supposed to let everybody know how much Warner Bros. has spent to keep you distracted. (At least that last Dark Knight movie tried to be clever with its post-traumatic red herrings.) I think I also agree with this writer that there was something especially unnerving about the last of its climaxes — and not in a good or even terribly imaginative way; while I can’t believe I’m still not trying to spoil anything at this point, that climax also looked as if the movie makers were trying to extricate themselves (literally) from a corner & copped out with the least fuss possible.

To sum up: Rather than open new ways to expand or interrogate the Superman myth, this movie turns him into just another action hero who, though he may indeed be hotter than any other (at this point, the only thing people keep talking about after the show’s over is Henry Cavill’s off-the-charts eye-candy quotient) doesn’t exactly make you curious to see where he goes next. And maybe that’s the movie’s biggest problem. But it may also be a problem with our first true superhero, the template upon which all others have been fashioned. The novelty of seeing a man fly faster than sound has worn off, though we’ll never get tired of seeing him surprise others with his feats of strength. (Those vignettes of Clark wandering from one grimy outpost to another, leaving shock and awe in his wake, make up what genuine charm the movie carries.) However Man of Steel ultimately fares in the marketplace, I don’t think they’ll leave the story hanging this time. But rather than whatever the movie’s detractors claim to miss in wit and charm, I’d settle for the simple pleasures of the unexpected next time around.

For instance — and this is in no way a knock on Amy Adams, to whom I remain avidly (avidly) devoted — but, I mean, what about…I mean…why not:

As I said, a sense of wonder….

June 12th, 2013 — jazz reviews

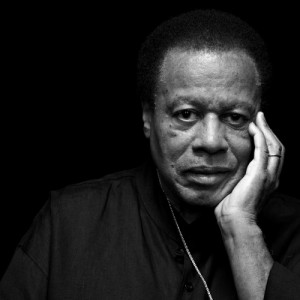

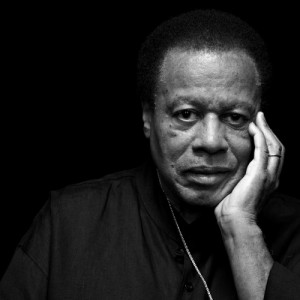

1.) During the one time I interviewed Wayne Shorter, I asked why no one had ever asked him to compose a film score. This set him off on an epic soliloquy on how male movie stars walk from Bogart, Gable and Cagney to Lancaster, McQueen and (I think) Poitier. He got up out of his chair and gave brief, impromptu imitations. He even brought Kirk Douglas into the discussion by which time he got me so caught up in whatever he was saying that I tried to bring such contemporary-cool avatars as Douglas’s son Michael and Denzel Washington into the mix (to little avail). He digressed into matters of posture, pace and the way people sway their arms in stride. It was enrapturing, frenzied and elliptical; like much of his music, only with words. I didn’t, couldn’t write any of it down because I knew I’d never get it in my paper. I wish I could find the tape, though. I also wish he’d answered my original question – and still wish that that somebody, anybody else would, too.

1.) During the one time I interviewed Wayne Shorter, I asked why no one had ever asked him to compose a film score. This set him off on an epic soliloquy on how male movie stars walk from Bogart, Gable and Cagney to Lancaster, McQueen and (I think) Poitier. He got up out of his chair and gave brief, impromptu imitations. He even brought Kirk Douglas into the discussion by which time he got me so caught up in whatever he was saying that I tried to bring such contemporary-cool avatars as Douglas’s son Michael and Denzel Washington into the mix (to little avail). He digressed into matters of posture, pace and the way people sway their arms in stride. It was enrapturing, frenzied and elliptical; like much of his music, only with words. I didn’t, couldn’t write any of it down because I knew I’d never get it in my paper. I wish I could find the tape, though. I also wish he’d answered my original question – and still wish that that somebody, anybody else would, too.

2.) In the summer of 2001, he appeared – materialized? – at New York’s JVC Jazz Festival in one of the first live appearances of the quartet that many now consider the best small combo in jazz. (This is by no means a unanimous opinion; more later about this.) So much time had passed since people heard him playing acoustic jazz with a rhythm section that there were several red-zone levels of anticipation for this show, the closing act of a three-tiered bill that, if memory served, included a crowd-pleasing Chick Corea set. The house fell in on him as soon as he walked on-stage. But the glow receded as soon as he started playing. He seemed reticent, even tentative, as if he were still hugging corners of the shadow-world in which he’d embedded himself for most of the previous decade. It wasn’t quite the rouser everyone in Avery Fisher Hall was amped for and one remembers how deflated even the most indulgent true believers looked as they filed out that night — though, to be fair, that acoustically-challenged venue may not have been the most ideal for a quartet seeking a détente between rumination and momentum.

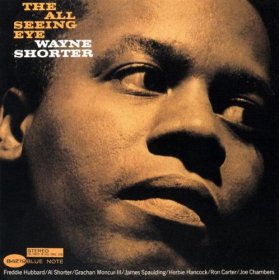

3.) On the other hand, what else DID they expect? A John Coltrane-style secular-mystical revival, radiant fire breathing and all? That’s not what you anticipate – or even desire – from Wayne Shorter, though he’s certainly proven himself capable of such incantatory drive. (I don’t know how many times I’ve played Juju among friends and found those unfamiliar with the album swear that it was Coltrane playing that tenor, even after I’ve told them otherwise.) Shorter, going all the way back to his mid-1960s tenure with Miles Davis (and more so with his Blue Note albums of that period) always connected with the writer within me. He had a distinctive, near-oblique narrative voice: lyrical, inquisitive, restless, but always with a solid harmonic foundation bracing his often-eccentric digressions. The sound of his saxophone didn’t swallow you whole as Coltrane’s could, but rather carried you along like a magical-realist storyteller. As with the best music of that era, Shorter’s playing and composing didn’t impose their mystique upon you so much as invite you to come up with your own poetic responses. George Harrison would have understood where Shorter was coming from – and for all I know, likely did.

4.) I just now remembered something else from that interview: His abiding interest in comic books and in one series in particular featuring a dauntless young aviator named “Airboy.” (There was one other hero whose name now escapes me. I’ve GOT to find that tape!) It occurred to me at that moment to ask why he never wrote a tune with “Airboy” as a title, but somehow we got caught up on another subject.

5.) As for writing a score for movies….what the hell. The way Hollywood is now, he’d be a lot better for them than they’d be to him. Best to make up your own movies in your head while listening to “Chief Crazy Horse” or “Mah-Jong” or “Schizophrenia” or “Over Shadow Hill Way” or “Calm” or “Face of the Deep” or “Deluge” or “The All-Seeing Eye” and…Know what? Even some of the titles, when you throw them in the air come across like some allusive, inscrutable and faintly volatile Shorter solo when they hit the page.

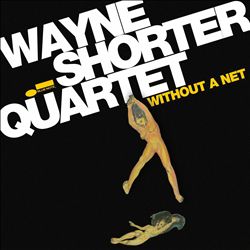

6.) So then…what about the other guys – Danilo Perez on piano, John Patitucci on bass and Brian Blade on drums? Do they and their leader deserve to be mentioned in the same breath as the Davis-Shorter-Hancock-Carter-Williams tandem – or any other classic small-jazz group that you can think of? Maybe it’s enough that Shorter always looks on-stage as if he’s overjoyed to be with them. I always had the feeling that from the start of their association, each member of the rhythm section was using his own resources to draw Shorter further out into the open. If their latest album, the aptly titled Without a Net (Blue Note) is any indication, they’re still tugging, coaxing and, especially in Blade’s case, shoving Shorter towards the deeper end of the pool. Often, it sounds as though he’s hanging back at the start, letting his fellas set the table before allowing whatever’s in his head seep or leap into view. Hence his off-the-cuff rendering of the “Lester Leaps In” theme that opens “S.S. Golden Mean,” which seems calculated to get Patitucci, Perez and Blade to ramp it up a little more. They do and this in turn gets Shorter to toss more angular shards of phrasing at unexpected times. (See what you do with this one! Wait! Think fast! I got another one.) Taking in all this freewheeling interplay is like making one’s way through a murder mystery written by a surrealist poet. There are enough familiar signposts of the genre to string you along, but the prose trips you up as often as the plot.

7.) On record, it’s engrossing; on-stage, it’s challenging, but no more so than a Bartok string quartet. (You’ll have plenty of opportunities to find out as the beginning of Shorter’s ninth decade is celebrated in live performance here and elsewhere throughout the year.) Still, many listeners coming with their own preconceived notions of what jazz is, or should be, find this quartet’s method too arbitrary and unfocused. Some might suspect the quartet’s colloquies are little more than expanded, busier editions of the airy, abstracted interplay in which Shorter and his old friend Herbie Hancock engaged with mixed results in their 1997 duet album, 1+1 (Verve).

8.) I’m nowhere near as negative, but I understand why others are. When Shorter edged his way back into full view less than twenty years ago, I hoped he’d carry with him some hooks and melodies evoking the familiar, relative solidity of “Speak No Evil” or “Adam’s Apple” – which, lest any of us forget, were considered pretty far out in their own time by those who left their hearts and heads with hard bop and cool jazz. It would seem that Shorter, whose place in history as a composer is safe and secure, now wants to find ways of inventing off the imperatives of a given moment, just as Miles Davis insisted on doing to the end. He’d just as soon share such moments with his team, the better to see where they can take him. I don’t mind the extra work they give me because as a listener, I’m taking the leap with them. True, I wouldn’t mind a net, or even a soft, wet towel at the bottom. But if “Airboy” can fly through the thickest, stickiest obstacles, Shorter believes we should at least try. You may come out the other end thinking bigger than you did before — or at least, more different.