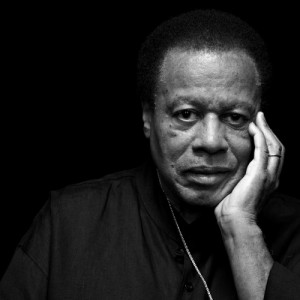

1.) During the one time I interviewed Wayne Shorter, I asked why no one had ever asked him to compose a film score. This set him off on an epic soliloquy on how male movie stars walk from Bogart, Gable and Cagney to Lancaster, McQueen and (I think) Poitier. He got up out of his chair and gave brief, impromptu imitations. He even brought Kirk Douglas into the discussion by which time he got me so caught up in whatever he was saying that I tried to bring such contemporary-cool avatars as Douglas’s son Michael and Denzel Washington into the mix (to little avail). He digressed into matters of posture, pace and the way people sway their arms in stride. It was enrapturing, frenzied and elliptical; like much of his music, only with words. I didn’t, couldn’t write any of it down because I knew I’d never get it in my paper. I wish I could find the tape, though. I also wish he’d answered my original question – and still wish that that somebody, anybody else would, too.

1.) During the one time I interviewed Wayne Shorter, I asked why no one had ever asked him to compose a film score. This set him off on an epic soliloquy on how male movie stars walk from Bogart, Gable and Cagney to Lancaster, McQueen and (I think) Poitier. He got up out of his chair and gave brief, impromptu imitations. He even brought Kirk Douglas into the discussion by which time he got me so caught up in whatever he was saying that I tried to bring such contemporary-cool avatars as Douglas’s son Michael and Denzel Washington into the mix (to little avail). He digressed into matters of posture, pace and the way people sway their arms in stride. It was enrapturing, frenzied and elliptical; like much of his music, only with words. I didn’t, couldn’t write any of it down because I knew I’d never get it in my paper. I wish I could find the tape, though. I also wish he’d answered my original question – and still wish that that somebody, anybody else would, too.

2.) In the summer of 2001, he appeared – materialized? – at New York’s JVC Jazz Festival in one of the first live appearances of the quartet that many now consider the best small combo in jazz. (This is by no means a unanimous opinion; more later about this.) So much time had passed since people heard him playing acoustic jazz with a rhythm section that there were several red-zone levels of anticipation for this show, the closing act of a three-tiered bill that, if memory served, included a crowd-pleasing Chick Corea set. The house fell in on him as soon as he walked on-stage. But the glow receded as soon as he started playing. He seemed reticent, even tentative, as if he were still hugging corners of the shadow-world in which he’d embedded himself for most of the previous decade. It wasn’t quite the rouser everyone in Avery Fisher Hall was amped for and one remembers how deflated even the most indulgent true believers looked as they filed out that night — though, to be fair, that acoustically-challenged venue may not have been the most ideal for a quartet seeking a détente between rumination and momentum.

3.) On the other hand, what else DID they expect? A John Coltrane-style secular-mystical revival, radiant fire breathing and all? That’s not what you anticipate – or even desire – from Wayne Shorter, though he’s certainly proven himself capable of such incantatory drive. (I don’t know how many times I’ve played Juju among friends and found those unfamiliar with the album swear that it was Coltrane playing that tenor, even after I’ve told them otherwise.) Shorter, going all the way back to his mid-1960s tenure with Miles Davis (and more so with his Blue Note albums of that period) always connected with the writer within me. He had a distinctive, near-oblique narrative voice: lyrical, inquisitive, restless, but always with a solid harmonic foundation bracing his often-eccentric digressions. The sound of his saxophone didn’t swallow you whole as Coltrane’s could, but rather carried you along like a magical-realist storyteller. As with the best music of that era, Shorter’s playing and composing didn’t impose their mystique upon you so much as invite you to come up with your own poetic responses. George Harrison would have understood where Shorter was coming from – and for all I know, likely did.

4.) I just now remembered something else from that interview: His abiding interest in comic books and in one series in particular featuring a dauntless young aviator named “Airboy.” (There was one other hero whose name now escapes me. I’ve GOT to find that tape!) It occurred to me at that moment to ask why he never wrote a tune with “Airboy” as a title, but somehow we got caught up on another subject.

5.) As for writing a score for movies….what the hell. The way Hollywood is now, he’d be a lot better for them than they’d be to him. Best to make up your own movies in your head while listening to “Chief Crazy Horse” or “Mah-Jong” or “Schizophrenia” or “Over Shadow Hill Way” or “Calm” or “Face of the Deep” or “Deluge” or “The All-Seeing Eye” and…Know what? Even some of the titles, when you throw them in the air come across like some allusive, inscrutable and faintly volatile Shorter solo when they hit the page.

6.) So then…what about the other guys – Danilo Perez on piano, John Patitucci on bass and Brian Blade on drums? Do they and their leader deserve to be mentioned in the same breath as the Davis-Shorter-Hancock-Carter-Williams tandem – or any other classic small-jazz group that you can think of? Maybe it’s enough that Shorter always looks on-stage as if he’s overjoyed to be with them. I always had the feeling that from the start of their association, each member of the rhythm section was using his own resources to draw Shorter further out into the open. If their latest album, the aptly titled Without a Net (Blue Note) is any indication, they’re still tugging, coaxing and, especially in Blade’s case, shoving Shorter towards the deeper end of the pool. Often, it sounds as though he’s hanging back at the start, letting his fellas set the table before allowing whatever’s in his head seep or leap into view. Hence his off-the-cuff rendering of the “Lester Leaps In” theme that opens “S.S. Golden Mean,” which seems calculated to get Patitucci, Perez and Blade to ramp it up a little more. They do and this in turn gets Shorter to toss more angular shards of phrasing at unexpected times. (See what you do with this one! Wait! Think fast! I got another one.) Taking in all this freewheeling interplay is like making one’s way through a murder mystery written by a surrealist poet. There are enough familiar signposts of the genre to string you along, but the prose trips you up as often as the plot.

7.) On record, it’s engrossing; on-stage, it’s challenging, but no more so than a Bartok string quartet. (You’ll have plenty of opportunities to find out as the beginning of Shorter’s ninth decade is celebrated in live performance here and elsewhere throughout the year.) Still, many listeners coming with their own preconceived notions of what jazz is, or should be, find this quartet’s method too arbitrary and unfocused. Some might suspect the quartet’s colloquies are little more than expanded, busier editions of the airy, abstracted interplay in which Shorter and his old friend Herbie Hancock engaged with mixed results in their 1997 duet album, 1+1 (Verve).

8.) I’m nowhere near as negative, but I understand why others are. When Shorter edged his way back into full view less than twenty years ago, I hoped he’d carry with him some hooks and melodies evoking the familiar, relative solidity of “Speak No Evil” or “Adam’s Apple” – which, lest any of us forget, were considered pretty far out in their own time by those who left their hearts and heads with hard bop and cool jazz. It would seem that Shorter, whose place in history as a composer is safe and secure, now wants to find ways of inventing off the imperatives of a given moment, just as Miles Davis insisted on doing to the end. He’d just as soon share such moments with his team, the better to see where they can take him. I don’t mind the extra work they give me because as a listener, I’m taking the leap with them. True, I wouldn’t mind a net, or even a soft, wet towel at the bottom. But if “Airboy” can fly through the thickest, stickiest obstacles, Shorter believes we should at least try. You may come out the other end thinking bigger than you did before — or at least, more different.