I had not only hoped, but also expected that Mulgrew Miller would have one of those lives and careers that endured for decades longer than he was allotted. He seemed destined to become one of those gray eminences of the jazz keyboard who would be around for another generation or two as a living exemplar of jazz piano’s essential verities very much in the manner of Hank Jones, Tommy Flanagan, John Hicks, Kenny Barron and Barry Harris. He’d found a niche at William Paterson University as director of jazz studies in which role he formally – and from the evidence here, effectively – carried out what he’d been doing informally since his 20s: influencing and mentoring younger musicians eager to follow his example.

As others have been pointing out since yesterday and will likely continue to do so over the next several days, Mulgrew Miller played with a faultless blend of grace, lyricism, clarity and unassuming resourcefulness that threaten to attract the label of “jazz pianist’s jazz pianist.” While this is intended as a compliment (and there are far worse things people can say about you), it also feels reductive, inexact and inefficient – especially when one gazes at the vast and expanding field of jazz pianists who have legitimate claim to that title. Each of us, in whatever trade or calling we pursue, is the sum of our accumulated influences and experiences; it’s what we do with that internal file that matters. When I listen to Miller play, I hear a generosity of spirit, inventive enough to keep your attention, yet deeply grounded in the rhythmic and harmonic foundations of what, for want of a better term, is considered “post-bop” jazz. You don’t always have to bend or twist tradition out of shape in order to get a rise out your listeners. You can endow the familiar with such authority, power and dynamism that it achieves a kind of eloquence that lingers in the imagination. As a leader and as a sideman, Miller hit those points so frequently that he created his own posse of devotees who followed him from an evening’s session at the late, lamented Bradley’s in the Village to whatever album was lucky enough to have him in the roster.

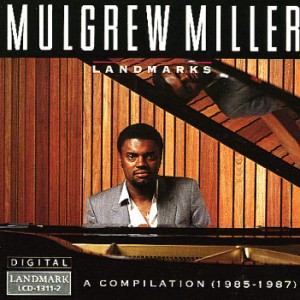

I’m lucky, in any event, to still have some of the now out-of-print discs he recorded in the early-to-mid-1990s for Orrin Keepnews’ Landmark label and on Steve Backer’s Novus series. (My favorite from the former: 1992’s Time and Again; from the latter, 1995’s With Our Own Eyes. They’re both worth hunting for in used-music bins, on- or off-line.) He also assembled quite a catalog as a leader on the MaxJazz label, especially the two-disc Live at Yoshi’s trio sessions. He always seemed so prolific and busy that you took it for granted that his protean work ethic would receive even greater rewards further down the road with the kind of wider recognition that reached Flanagan, Jones and others in their golden years. But he – and we – have been cheated out of that prospect. Dammit. Again.