There’s so much stuff to keep track of these days that it’s easy to lose track of stuff that seemed so great to watch, read, or even glean. So, this took a longer time to assemble than previous lists because it took that long a time to process the maelstrom that was 2022. I’m not going to tell you what I think is missing here because you’ll all have your own lists, some of which will likely include, say, the January 6th hearings or Everything Everywhere All at Once. The Multiverse itself likely deserves a slot all its own, except how do I know I don’t have a whole other list somewhere that’s all different. But there’s no time left to figure all that out. This is what I’m going with, and, except for the very last item, I feel altogether good about it. As always, these are not in any particular order – except, again, for the last one.

Reservation Dogs – Two things, I’ve recently decided, make life worth living: a sense of purpose and an active connection with each other’s souls, no matter how remote or hostile. Such were the animating forces of Sterlin Harjo and Taika Waititi’s poignant blend of teen anomie, vacant-lot naturalism, and stoner surrealism. As with its predecessor, Season Two found its indigenous American kids adrift in their ramshackle Oklahoma hood, still grieving the suicide of their friend Daniel and still getting haphazard and not altogether lucid counsel from varied elders, living and dead. My personal favorites among the latter demographic include, among the dead, William “Spirit” Knifeman (Dallas Goldtooth), a Lakota ancestor to confused-and-abandoned Bear (D’Pharoah Woon-A-Tai), whose half-baked advice to his teen descendant include lyrics from “Carry On Now Wayward Son” (yes, that one); among the living, it’s a three-way tie between Officer Big (Zahn McClarnon), a tribal policeman who stumbles his way towards a wholly innate sense of law, order, and even (such as it is) justice; woozy, weed-mongering Uncle Brownie (Gary Farmer), and the oracular-if-shabby Bucky (the great Wes Studi), with his hard-won cosmic wisdom. Still, it’s the kids who occupy the series’ fitful center; not just Bear, but also Cheese (Lane Factor), Willie Jack (Paulina Alexis), and Elora (Devery Jacobs), whose single-minded path towards California anchored the second-season narrative, and now appears ready to affect her friends’ destinies. Whatever happens and wherever all the rest of the grownups and kids end up, I hope I see more of those rapping, bike-riding bros LilMike and FunnyBone. Even if I don’t, I’ll happily settle for more Bucky and Brownie.

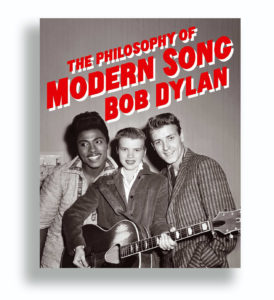

The Philosophy of Modern Song — Don’t call it “Bob Dylan’s Pop-Rock Criticism” or apply any socio-political ideology to its 60-plus selections. More than anything else, this is the authentic follow-up to Dylan’s 2004 memoir, Chronicles, Volume One and should be acknowledged as the autobiography of a personal aesthetic. Its illustrations and its text are as illuminating, evocative, cryptic, funny, and exploratory as “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream,” “From a Buick 6,” “Positively 4th Street,” or any other Dylan song, even those with no numerals in them. Also as with a Dylan song, whatever its intentions or origins, much of the raw content of these mini-essays, addenda, outbursts, and eruptions may arouse your subconscious to something it never considered before but recognizes as familiar. And no, I’m not going to explain what I mean by that. (At least not here. Later on, I do. Sorta.)

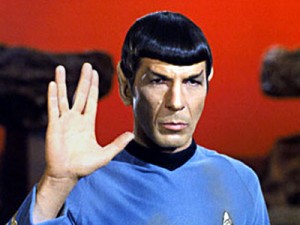

Star Trek: Lower Decks – I’ll always place Matt Groening’s ribald space opera Futurama first above equals among animated science fiction TV series, even above the underappreciated, trailblazing, and scarily prescient Jetsons, which marked its 60th anniversary this year. Nevertheless, after three seasons, this doughty, wily offshoot of the ever-expanding-like-the-universe-itself Trek franchise has not only leaped towards the front of this personal pantheon, but it also threatens to become my favorite among the Trek shows that streamed into being over the last five years. As its title implies, the show moves its focus away from the Alpha Dogs of Star Fleet like Kirk, Spock, Sulu, Picard, Riker, La Forge, and other Heroes on the Enterprise Bridge and more towards the scrubs, swabs, and junior grade drudges several floors down from whose ranks would routinely come cannon fodder with imperiled landing parties in previous Trek incarnations. The series’ core clique waiting and serving on the USS Cerritos (itself a relative second-stringer among Star Fleet ships) is made up of science nerd D’Vana Tendi (Noêl Wells), super-striving Brad Boimler (Jack Quaid), sweet-tempered cyborg Sam Rutherford (Eugene Cordero), and last-and-certainly-not-least Beckett Mariner (Tawny Newsome), thorny, determinedly underachieving daughter of the ship’s captain Carol Freeman (Dawnn Lewis), whose own insecurities and thwarted ambitions are of such comparable dimension that you come away from this ingenious, often touching series affirmed that even in deep space, nobody ever gets out of high school, dead or alive.

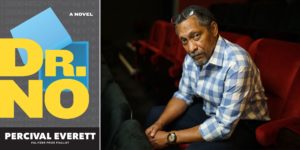

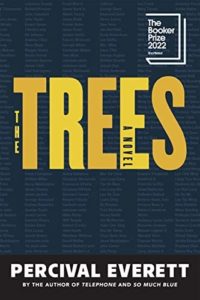

Percival Everett – Suppose Chester Himes was an actual cowboy who spent as much time working out ontological riddles as riding ranges and fishing in mountain lakes. At age 65, Everett, who claims Himes as an influence, along with Herman Melville, has published more than twenty works of fiction of startling range, deadpan humor, and formidable intelligence. This year, for instance, he published Dr. No, where he borrows both a title and a plotline from Ian Fleming’s James Bond’s novels to fashion a blackout-adventure spoof judiciously seasoned with red herrings and philosophical conundrums. If I told you it’s about Nothing, you’d still read it, right? You’d have to read it. But if I were you, I wouldn’t start with the new one, but the one just before that was short-listed for the Booker Prize: The Trees, a very different, but no less provocative and inspired comedy thriller in which cool, dry Black agents from, the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation (MBI) investigate the serial murders of white racists whose bodies are somehow accompanied by the corpses of long-dead lynching victims, including Emmett Till. It made you almost wish Hollywood had made this into a movie instead of Till. But Hollywood was barely ready for that straight-ahead story to be told on-screen. And I doubt it’ll ever be ready for Percival Everett. But you might be. (Other recommended titles: Glyph, Erasure, I Am Not Sidney Poitier, For Her Dark Skin, Damned If I Do.)

Nope – Though I honor the memory of Rod Serling and what he did for me as a child in the warm bath of his Twilight Zone, the grownup I am now is less drawn to those Serling-esque episodes making broad and direct sociopolitical points and more towards those Zone stories written by Richard Matheson and Charles Beaumont that were more interested in pure jolts and unsettling visions for their own sake. Maybe that’s why I think this third feature by Jordan Peele is his best thus far for the same reasons much of the word-of-mouth I’d heard when it came out was so antagonistic: it was all over the map, in both theme and tone; it didn’t sustain a straight storyline or deliver a hard, sharp point. And it left me with more to unravel and think/dream about than either Get Out or Us. Yes, there’s a racial subtext (what Hollywood did for, and mostly to its Black workers, on- and off-camera), but it’s only one of several layers in this aliens-from-outer-space movie that manages to evoke the dry-mouth aura of a 1950s drive-in chiller while being up to date with its eccentric supporting cast, especially the marvelous Keke Palmer as steely, feisty sister to Daniel Kaluuya’s dispirited horse trainer. For the record, Michael Abels’s score reaches new heights here, too. Almost as high, maybe higher, than the big black disc in the sky that causes all the trouble.

Abbott Elementary – As I’ve previously testified in public, I was so much in love at first sight with Quinta Brunson’s tender and whimsical workplace comedy series about an economically challenged South Philly public school that I took its premature cancellation as an inevitability. Now it’s a firmly established hit which may well be single-handedly rescuing the analog network sitcom from oblivion. Somewhere, Mister Peepers is grinning – and idly wondering how he’d cope with a principal like Ava Coleman.

Matthew Goode in The Offer — For most of Goode’s career, I thought I had him nailed down as a pleasant, perfectly comported prototype of the British smoothie capable of an eccentric tic (in the manner of British smoothies) or even a swerve into hysteria because of, say, combat fatigue from whatever beastly war harshed his erstwhile empire’s mellow. Watching him bring Robert Evans back to life in The Offer was a massive revelation. Those who know or have seen the 2002 documentary The Kid Stays in the Picture don’t need to be told that Evans was something of a Hollywood superhero in the mid-1970s when the movie business was generally lost at sea while the art form was at its peak. Evans’ one major misfire of that decade was The Great Gatsby and what you see in Goode’s evocation discloses where he went wrong: to do Gatsby right, what Evans really needed to do was to let cameras follow him around for a year and have somebody edit all the raw footage into a feature. That hypothetical verité could have been just as innovative and grand an achievement as both Godfathers and Chinatown. As it was, Goode’s rendering of a Gatsby-esque Hollywood legend, a “Last Tycoon,” if you will, elevated an otherwise middling docudrama to near-classic tragedy.

Prey – This was the prequel to the Predator franchise than no one, not even those who don’t care about hunter-gatherers from outer space, knew they wanted until it materialized in front of them. Set in a primeval American Great Plains more than three centuries before Arnold Schwarzenegger was a gleam in his mother’s eye, the film stars the magnetic Amber Midthunder as Nuru, an indigenous young warrior itching to show her brother and the other young tribesmen that she’s as great at stalking and hunting as they are. But the first in a series of hairy, insect-faced extraterrestrial hunters begins to pick off the incredulous young braves, eventually leaving her to figure out how to protect the rest of her village from being harvested. The special effects are, in their elemental way, just as spectacular as the hi-tech pyrotechnics of previous installments. (You will believe a bear can fly.) But Midthunder is, on many levels, the most dazzling of the movie’s assets, her character’s intensity and self-possession announcing both a young woman’s coming-of-age and a screen star’s arrival.

Atlanta: The Final Season(s) – Where to begin? The crew’s WTAF adventures during Paper Boi’s (Bryan Tyree Henry) European tour, including strange encounters with, among others, a friendly-but-oddly-abusive Liam Neeson, some well-heeled gourmet cannibals, a Blackface Dutch Christmas icon, along with streams of misread signals, overpriced fashion goods, exotic and dangerous drugs, and a missing phone. Or what about the seemingly “free-standing” stories, including the one about the wealthy white Manhattanites who discover their little boy is emotionally and psychically closer to their recently deceased Caribbean caregiver? Things got even weirder when Earn (creator-producer Donald Glover) and his posse returned to Atlanta where things are as dislocated as ever; how Van (Zazie Beets) somehow ends up searching for her daughter within a sinister cult-like entertainment complex run by the exploitative, enigmatic Mister Chocolate (Glover), all of it finishing off somehow with harrowing adventures in sensory deprivation with perpetually stoned Darius (Lakeith Stanfield). And that just scrapes the surface of this layers-within-layers, worlds-within-worlds cultural excursion that resembled exactly nothing else anywhere on any screen. They say it’s over. Not in my head, it isn’t.

Top Gun: Maverick – This is on the list primarily for its significance as a cultural phenomenon and not so much because it’s a great, or even very good movie. Not that I didn’t like it. In fact, I liked it a whole lot more than its 1986 predecessor, when its star’s grin was devouring everything in its path, symbolizing both the era’s avarice and obliviousness. TG:M provided such a massive, exhilarating surge to theaters struggling to shake loose from the COVID-19 doldrums that some audiences used the word “great” without qualification or irony. There were great things in it, most having to do with aerial ballet. But as all-American paeans to duty go, I much prefer John Ford’s calvary trilogy (Fort Apache, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, Rio Grande) and even with Ed Harris around for the first act, I’d still rather watch The Right Stuff than either Top Gun movie.

In that first act (and if I’m really spoiling things for you here, then, dammit, go watch it on a streaming channel), Tom Cruise’s Maverick flies a state-of-the-art craft based on the now-decommissioned SR-71 “Black Bird” modified to reach Mach 10. Harris’s crusty admiral is about to shut down the manned flight experiment in place of drones, which kinda sorta makes sense. But “Mav” being “Mav”, he takes the plane up into the stratosphere and not only reaches the optimum speed but decides to stretch that old envelope a tad past Mach 10, which causes the plane to break up in flight. The next thing you see is Maverick, woozily lugging his parachute into a small-town diner, chugging ice water and asking where he is to which a small boy replies, “Earth.”

Now I don’t claim to be an aeronautical engineer. But I’ve absorbed enough histories of test flight and space travel to know that any corporeal being who even tries to eject from a flying object traveling past Mach 5 (a.k.a. hypersonic speed) will at the very least break every single bone and rend almost every tissue in its body, even in the highly unlikely event that a parachute opens. I’ve heard explanations (a.k.a. excuses) that the plane was likely equipped with some manner of “escape pod” that broke away and carried its pilot safely to the ground.

Yes, well…

It’s only a movie, right? And a movie that works so conscientiously to please its audience as Top Gun: Maverick needs to sacrifice credulity to roll the turnstiles and leave everybody happy.

But suppose, just suppose, that what we see when that plane breaks up high in the sky is the death of Captain Pete Mitchell, USN? And what if everything we see afterwards, including – and especially – Maverick’s reunions with his ailing wingman and the embittered son of the Lost Goose, make up an extended posthumous dream sequence, a Sixth Sense with G suits and F-35s? You’d have a less satisfying popcorn epic. You might also have a resonant masterwork of American storytelling.

As it stands now, it’s likely the loudest, most ornately apportioned shout of “olly-olly-oxen-free” ever issued to the moviegoing public. Thus, it’s a masterstroke of some kind. But not quite the one we, or the movies, really needed.