June 15th, 2015 — jazz reviews

OK, Stranger Than Paradise, right? Jim Jarmusch? 1984? That one. See it soon, if you haven’t yet. Holds up pretty well.

That’s not the main reason I’m calling this meeting, but anyway…

Remember how Screamin’ Jay Hawkins original 1956 recording of “I Put A Spell On You” was a recurring motif because it was the only record that Eva (Eszter Balint), the movie’s truculent teen-aged Hungarian émigré, wanted to listen to? Now remember, also, when Eva gets into a car with Eddie (John Lurie), her lizard-cool cousin from the Lower East Side, and his not-quite-as-cool sidekick Eddie (Richard Edson) for a New York-to-Cleveland road trip and she insists they put on her Screamin’ Jay tape. And even though Willie’s borderline-sick of the tune, Eddie’s really into it.

“This,” Eddie proclaims, “is driving music!”

Well now…

Last Friday afternoon, I drove from Bloomfield, Connecticut to Brooklyn, New York, a three-and-a-half-hour trip that ended up being more like five hours. (I did mention it was a Friday afternoon.) And in tribute to Ornette Coleman, who had joined the ancestors the day before, I had my IPod patched into my car speakers and locked throughout on Total Ornette Shuffle, covering the gamut from his 1958 Something Else Pacific Jazz sessions through the groundbreaking Atlantic sides including The Shape of Jazz to Come, Free Jazz and This Is Our Music, and the funky electro-boogie of his Prime Time band all the way to his 2007 live concert disc Sound Museum that helped him win a Pulitzer Prize.

By the time I crawled off the Van Wyck and squeezed myself onto the Jackie Robinson Parkway, I was struck dumb by the following revelation: Ornette Coleman is kickass driving music! It doesn’t matter whether you’re cruising through the woods or mired in gridlock. Coleman’s music in all his varied settings, even on his inflammatory -at-the-time tenor album from 1962, can transfix you into a state that’s somehow both chillaxed and vigilant. In some quadrants, it’s called being Very Much Alive To Your Moment. Whatever you call it, it’s odd (but not really) that I’m somehow more attentive to Coleman while in motion than when sitting still, either when watching him live or listening to his records.

Indeed, I was fond of telling city folk of varying ages claiming they could not, or would not ever engage Ornette Coleman’s compulsively renegade art that in the era of digital-portable music being piped inside one’s head, there were rewards and maybe even illumination to be found in letting, say, “Lonely Woman.” “Change of the Century,” or “Song X” weave through the beautiful mosaic of ambient urban sound. Whether your day needed added propulsion or a demilitarized zone, the music, at any tempo or tone, could provide both. To think that there are people who remember when all this music was able to do was make people mad — even those who should have known better, and eventually did.

Did anybody take me up on it? Don’t know, don’t care, because I kept at it even though I knew what I was up against: Trying to explain “harmolodics.” It was Coleman’s own term for his aesthetic principles, and while there is no altogether satisfying definition for the word, it may be characterized in part as organic music that invents and re-invents itself off improvisation itself and not on chords. Even though his music has been around for at least a couple generations, there are those who still have trouble with the harmolodic concept, however much the music associated with it evokes powerful strains of both bebop and the blues at full cry.

Listen to that saxophone! I would say to the hardheads. If a singer made those sounds, you’d be swooning, swaying and even rocking with it. Those sounds over time did make my point, and then some. I’m hardly the first to insist that, however much Coleman’s ringing, vibrating tone was associated with all things modern and abstract, there was also something about his phrasing that was deep-rooted, even embryonic. But then there was the music’s relationship with its rhythm section. What was there to hold onto? the hardheads complained. I insisted that were always beats you could not only ride, but also dance to, if you bothered to look for them.. The problem (I always added mostly for their benefit) was that the dancing that went along with those beats hadn’t been invented yet.

That last part, of course, is so very wrong. Lost of people I knew did dance to Coleman’s music; sometimes spontaneously, even organically off the improvisations as the music mandated; and sometimes, as they did at Lincoln Center in the summer of 1997 to the jams laid down by that aforementioned Prime Time band. This was at the climax of a weeklong tribute to All Things Ornette, whose sundry participants included the New York Philharmonic and the downtown power company known as Lou Reed and Laurie Anderson. I reviewed that festival for Newsday, concluding somewhat cheekily that we’d all been living in Coleman’s world for decades now, only we’re now beginning to notice it.

I’d still like to believe that, especially given the play given last week to Coleman’s passing in major news outlets. Yet there somehow seemed greater attention paid in mass-market precincts to Christopher Lee, the venerable British character actor and horror-movie cult star, whose death was reported the same day. I’m as much in thrall to movie cults as any dork, but there’s a very big difference between being a reliably accomplished bogeyman and changing the furniture in people’s heads.

Yet the deep sadness that reverberates among those who do appreciate Coleman’s significance over his death comes from two places. One is the belief that, even at 85, he was ready and able to keep working in public. (There was at least one scheduled tour date for later this year, in Paris.) The other, more complicated, resides in a melancholy suspicion that with Ornette Coleman’s departure, we’re also saying goodbye to the future; or perhaps more to the point, a belief in the future’s possibilities. The risks he took back in the fifties embodied jazz’s last great modernist convulsion. As long as he was around, it was possible to imagine him still leading the charge for further discovery.

But as long as there remain multitudes out there who still don’t quite “get” what Coleman was up to, the future he mapped out will always be with us, indoctrinating new enlistees in the harmolodic cause, tempting fresh crops of painters, poets, dancers and, of course, musicians in all marketing categories to think organically – or think different, at least. As I wrote 18 years ago, it’s still Ornette’s world, no matter how long it takes for the rest of that world to figure it out.

In the meantime…If you think you’re missing something in Ornette’s music and really wish to “know” more, the way to do it is not by sitting rock-still and barber-close to the speakers hoping to somehow catch a key phrase or progression that will somehow reveal the universe’s secrets. Take the music with you when you move, whether on foot or in a vehicle. When his sounds merge with the colors, sensations, thoughts and white noise passing through you, they still may not make anything resembling what you consider “sense, but they may well pry open your senses to new ways of living and feeling your way through time. There are, as Art always knows, no conclusions and Art doesn’t want you to find them anyway. Art says: Here are new frequencies and stations for you to follow. Carry them with you and everything you think is old may turn out to be shrink-wrapped and shiny.

December 18th, 2014 — movie reviews, on writing lit -- and unlit, TV reviews

Because I don’t have to, I’m not going to bother with a Top-Ten movie list this year. This is also because there wasn’t a whole lot I saw at the multiplexes in 2014 that got me as wound up as the stuff I’m listing below. And if I bothered to enumerate the movies that did, I’d likely end up with a list that more or less looks like everybody else’s, which precisely none of us wants.

Instead, I’m going to pull together a rag basket of items that for various reasons made the most resounding connections with my frontal lobes through the prevailing media din of weapons-grade white noise and free-styling schaudenfreude. Most came out this year; some didn’t, but I got around to them for the first time this year, so they count. (My list, my rules.)

Quite likely, I’m forgetting, or blocking some stuff. It’s been that kind of year. And there were some things I couldn’t bring myself to include, whatever my absorption level. Scandal, to take one example, remains for many people I trust an irresistible sack of Screaming Yellow Zonkers. But outside of Joe Morton’s righteously Shatner-esque scenery chewing and the mad electricity vibrating in Kerry Washington’s eyeballs, I’ve found that its live-action anime antics can go on without me for at least a couple weeks at a time.

So anyway…(as this fellow might out it)

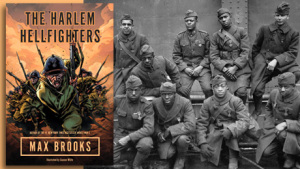

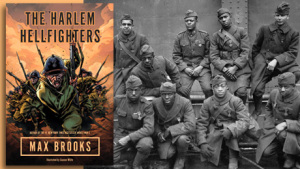

The Harlem Hellfighters by Max Brooks –Brooks made his name mythologizing the walking-dead (World War Z, The Zombie Survival Guide). But he proves himself just as conscientious in rendering factually grounded savagery in this fire-breathing graphic (in every sense) novel about the legendary all-black 369th Infantry Regiment that roared out of Harlem to fight in World War I, the hinge between post-Reconstruction’s legally-sanctioned terrorism of African Americans and the gathering pre-dawn of the civil rights movement. Though the Hellfighters’ passage from raw, often humiliated recruits to take-neither-prisoners-or-shit-from-anybody warriors is rousing, the visual depictions of squalor, disease and violence (thanks to the classic-war-comics élan of illustrator Canaan White) deepen the many ironies layered onto this saga; not the least of which was that it was only through the horrific, demeaning process of war that black men could begin proving their worthiness as American citizens – and even that wasn’t enough. To establish its own validity as historical fiction, Brooks’ account brings in such real-life badasses as James Reese Europe, Henry Lincoln Johnson and Henri Gouraud for colorful cameos. Of course, a movie is planned. Good luck trying to top this

Scarlett Johansson –I’ve already waxed rhapsodic about the commanding way she works the alien-enigmatic in the polarizing Under the Skin. By contrast, the art-house crowd showed relatively little-to-no-interest in Lucy in which she played a hapless, sponge-faced drug mule accidently injected with a drug transmuting her into a time-distorting, matter-altering, ass-kicking wonder woman. But Luc Besson’s acrylic pulp fantasy proved that few, if any movie actresses today are as cavalierly brilliant at throwing down wire-to-wire magnetism in such nutty eye candy. Manny Farber would have wallowed in the termite splendor of it all. Even her by-now borderline-gratuitous Black Widow turn in support of yet another Marvel money machine (Captain America: The Winter Soldier) retained enough droll slinkiness to make one suspect that giving the Widow her own vehicle might be a bit of a let-down. Then again, Ms. Scarlett never let me down once this year, so why dwell upon the purely speculative?

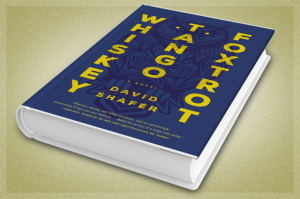

Whiskey Tango Foxtrot By David Shafer – This novel took me by surprise as it did several other critics this past summer. Up till that point, it hadn’t occurred to me that the legacies of both Richard Condon and Ross Thomas could, or even should be filled. Nevertheless, anyone whose familiarity with these authors’ works extends beyond Condon’s The Manchurian Candidate or Thomas’ The Fools In Town Are On Our Side will recognize Shafer’s sardonic humor, crafty plotting and humane characterizations as reminiscent of both authors – which is another way of saying these qualities aren’t what readers of contemporary techno-thrillers are used to. Also, much like Condon, Shafer knows, or strongly suspects, what we’re all afraid of, deep down, and finds a surrogate for this fear that’s both outrageous and plausible; in this case, a sinister cabal of one-percenters planning to seize total control of storing and transmitting information worldwide, thereby making recent abuses by the NSA, or whoever has it in for Sony Pictures, seem like benign neglect. This premise scrapes somewhat against territory controlled by what used to be called the “Cyberpunk School” as well as Thomas Pynchon, except that Shafer’s three 30-ish hero-protagonists are at once unlikely and recognizably human: an Iranian-American NCO operative who stumbles into the conspiracy so haphazardly she’s not sure what it is until it goes after her family, a self-loathing self-help guru in debt to his eyeballs who’s recruited by the cabal to be its “chief storyteller” and his estranged childhood friend, a substance-abusing misfit with a trust fund as thick as his psychiatric case file. They are all swept into an underground movement called “Dear Diary” which knows what the cabal is up to and is deploying its own secret network to bring it down. Social comedy, political melodrama and digital menace don’t always blend as well as they do here. And this is only Shafer’s first novel, meaning, as with the other masters cited above, he can only get better at this stuff from here on.

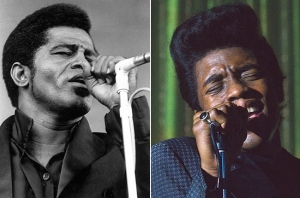

Get On Up & Mr. Dynamite: The Rise of James Brown – The former is a feature biopic; the latter an HBO-exhibited documentary. Both told me things I didn’t know about their shared subject – or, maybe more to the point, framing what I already knew about James Brown’s story in a manner that showed him as far more than an unholy force-of-nature. If I lean more towards the documentary, it’s because the revelations are more striking (not just the spectacular “what” of Brown’s showmanship, but the painstaking “how” of its components along with its savvy adjustments over time). And its testimonies are altogether more enlightening (Mick Jagger, who co-produced both, sets the record straight on how the “T.A.M.I. Show” sequence of acts really went down) I loved listening to band members let loose on what they really thought of their sometimes thoughtless boss as well as what second-generation Fabulous Flames as Bootsy Collins learned on and off the road from Brown. Tate Taylor’s biopic has a different agenda, but it strives to be just as faithful, if not always to the facts, to the facets of Brown’s fiery, hair-trigger temperament. Maybe it tried too hard. (As far as B.O. was concerned, Get On Up…didn’t.) But Chadwick Boseman’s, conscientious rendering of Brown’s tics and turbulence is almost as breathtaking to watch as one of the Godfather’s actual Soul Train appearances. Now that Boseman’s successfully portrayed two historic icons, I remain anxious to see what he can do with a Regular Guy role sometime between now and Marvel’s Black Panther movie.

FX– The third, and best, season of Veep; the harrowing, jaw-dropping single-take night scene in True Detective; Billy Crystal’s astute, heartwarming 700 Sundays; Girls and its discontents; the sheer how-can-it-possibly top-itself-again-and-again momentum of Game of Thrones…There was so much to love about HBO this year that I feel like an ingrate for professing my affection for a rival, even though there are things in both FX and HBO that I’ve neglected (American Horror Story, Boardwalk Empire) or shortchanged (The Strain, The Leftovers). Nonetheless anyplace I can find Louie, Archer, The Americans and (for me, especially) Justified is a cozy, stimulating home for my mind. Add to this the deep-dish pleasures of Fargo, whose greatness sneaked up on me the way Billy Bob Thornton’s meatiest, slimiest character since Bad Santa slithered through the frozen tundra, and of The Bridge, whose shrewd and nervy evolution from its first, somewhat derivative season went mostly unnoticed by the professional spectator classes and I’m not sure FX doesn’t have a deeper bench, pound for pound, than its bigger rivals., I prefer a lean, mean FX that takes so many worthy, edgy chances that it can be forgiven for something as lame and sad as Partners. (Never heard of it? Good. We shall speak no more.)

The Oxford American “Summer Music Issue” – I, along with many of my friends, have lots of reasons for being mad at the once-and-future Republic of Texas. But I still love its literary heritage and, most especially, its thick, spicy blend of home-grown music, which takes up C&W, R&B, Tex-Mex, swing, funk, hip-hop and even some avant-garde jazz courtesy of native son Ornette Coleman. They’re all represented on a disc accompanying a special edition of this always mind-expanding quarterly. Compiled by Rick Clark, this CD provides the kind of kicks your smarter buds used to slap together on cassette as a stocking stuffer. Besides the aforementioned Ornette (“Ramblin’”), there’s some solo Buddy Holly (“You’re the One”), early Freddy Fender (“Paloma Querida”), priceless Ray Price (“A Girl in the Night”) and the unavoidable Kinky Friedman (“We Reserve the Right to Refuse Service to You”). The left-field surprises include an especially noir-ish take of Waylon Jennings doing his signature “Just To Satisfy You,” a deep-blue rendition of “Sittin’ On Top of the World” by none other than Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys, Ruthie Foster’s espresso-laden performance of “Death Came a-Knockin’” and Port Arthur’s own Janis Joplin fronting Big Brother and The Holding Company on a “Bye, Bye, Baby” that swings as sweet as Julio Franco once did. I don’t want to shortchange the actual magazine, which includes James Bigboy Medlin’s reminiscences of working with Doug Sahm, Tamara Saviano’s portrait of Guy Clark and Joe Nick Patoski’s story about Paul English, Willie Nelson’s longtime drummer. It doesn’t beat a spring-break bar tour of Austin, but it’ll do until I get a real one someday.

July 23rd, 2014 — jazz reviews

As of this Friday, Charlie Haden will have been off the planet for two weeks. Yet I’m still tripping over him in unexpected places. Earlier this week, for instance, I put on an ECM compilation of Carla Bley’s work and all of a sudden, this voice pours out of the speakers that sounded a lot like Linda Ronstadt’s from her daisy-fresh Stone Poneys days. Turned out that’s exactly who it was: Ronstadt doing lead vocals on Bley’s “Why?” from the 1971 jazz opera, Escalator Over The Hill. And who should be vocally harmonizing with her on this track, in what sounds like the bluegrass idiom of his childhood professional days, but Haden, who also played double-bass for Bley’s orchestra.

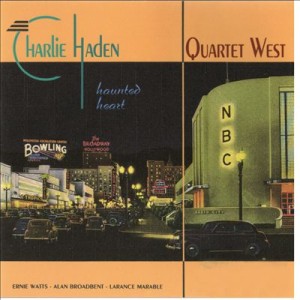

As of this Friday, Charlie Haden will have been off the planet for two weeks. Yet I’m still tripping over him in unexpected places. Earlier this week, for instance, I put on an ECM compilation of Carla Bley’s work and all of a sudden, this voice pours out of the speakers that sounded a lot like Linda Ronstadt’s from her daisy-fresh Stone Poneys days. Turned out that’s exactly who it was: Ronstadt doing lead vocals on Bley’s “Why?” from the 1971 jazz opera, Escalator Over The Hill. And who should be vocally harmonizing with her on this track, in what sounds like the bluegrass idiom of his childhood professional days, but Haden, who also played double-bass for Bley’s orchestra.  A day later, I finally caught hold of Last Dance, the recently-released ECM album with Haden and one of his old bosses, Keith Jarrett, performing classic pop standards. Though these duets were recorded in 2007, the album’s ruminative tone and sepulchral title, augmented by having “Every Time We Say Goodbye” and, then, “Goodbye” as back-to-back concluding numbers, seem to emit melancholy prophesy. Except I don’t feel in any way saddened while listening to these intimate conversations between two veterans who, though working with traditional chord progressions and stone-ground rhythms, find new ways to make these warhorses enrapture and inspire. Which may be another way of saying that nothing much has changed and Charlie Haden will somehow always be with us, letting his romanticist’s gospel of Beauty and Truth filter through the world where, through most of his 76 years, he spread this gospel broadly, but never thinly. We could be spending almost as many years wandering through and assessing his prolific contributions as sideman, leader, composer, collaborator and movie director. You read right. Movie director. And while you wont find his name listed as such on the Internet Movie Database, Charlie Haden excelled at making movies of the mind, even when he wasn’t trying. Born in 1937, Haden was a child of both motion pictures and the radio and, thus, instinctively understood how the former so robustly fed people’s imaginations, which were comparably stimulated by the latter. Just as the movies could make you want to get up and dance, orchestrated sounds could make you lie back and dream. By the 1950s, the movies would help dictate how we listen to music. (Think of all those set-the-mood-for-making-out LPs of the era with lush strings.) And Haden became one of the auteurs of concept albums that, openly or otherwise, borrowed their tropes from cinema. Most especially, what became known as the Hollywood noir movies of the forties and fifties became a recurring motif with Haden’s Quartet West albums on Verve, beginning with 1986’s eponymous album introducing the quartet – saxophonist Ernie Watts, pianist Alan Broadbent and drummer Billy Higgins, Haden’s onetime band mate with Ornette Coleman, replaced with Larance Marable on 1988’s In Angel City.

A day later, I finally caught hold of Last Dance, the recently-released ECM album with Haden and one of his old bosses, Keith Jarrett, performing classic pop standards. Though these duets were recorded in 2007, the album’s ruminative tone and sepulchral title, augmented by having “Every Time We Say Goodbye” and, then, “Goodbye” as back-to-back concluding numbers, seem to emit melancholy prophesy. Except I don’t feel in any way saddened while listening to these intimate conversations between two veterans who, though working with traditional chord progressions and stone-ground rhythms, find new ways to make these warhorses enrapture and inspire. Which may be another way of saying that nothing much has changed and Charlie Haden will somehow always be with us, letting his romanticist’s gospel of Beauty and Truth filter through the world where, through most of his 76 years, he spread this gospel broadly, but never thinly. We could be spending almost as many years wandering through and assessing his prolific contributions as sideman, leader, composer, collaborator and movie director. You read right. Movie director. And while you wont find his name listed as such on the Internet Movie Database, Charlie Haden excelled at making movies of the mind, even when he wasn’t trying. Born in 1937, Haden was a child of both motion pictures and the radio and, thus, instinctively understood how the former so robustly fed people’s imaginations, which were comparably stimulated by the latter. Just as the movies could make you want to get up and dance, orchestrated sounds could make you lie back and dream. By the 1950s, the movies would help dictate how we listen to music. (Think of all those set-the-mood-for-making-out LPs of the era with lush strings.) And Haden became one of the auteurs of concept albums that, openly or otherwise, borrowed their tropes from cinema. Most especially, what became known as the Hollywood noir movies of the forties and fifties became a recurring motif with Haden’s Quartet West albums on Verve, beginning with 1986’s eponymous album introducing the quartet – saxophonist Ernie Watts, pianist Alan Broadbent and drummer Billy Higgins, Haden’s onetime band mate with Ornette Coleman, replaced with Larance Marable on 1988’s In Angel City.  The other Quartet West Verves – 1990’s Haunted Heart, 1993’s Always Say Goodbye, 1995’s Now is the Hour and 1999’s The Art of the Song – were more or less pastiches of movie soundtracks, vintage recordings by such diverse artists as Jo Stafford, Jeri Southern, Chet Baker, Billie Holiday, Duke Ellington, Coleman Hawkins and Django Reinhardt. (In the last entry, a full orchestra and singers Shirley Horn and Bill Henderson joined the quartet in the studio.) Critics were mostly enchanted with these discs when they were first released, even though you could hear grousing from some corners that Haden was squandering his considerable energies on studio gimmickry; a kind of “sampling” for nostalgic grownups. But Haden had earned wellsprings of credibility that began to collect around his name in the late 1950s when he’d helped rearrange the furniture in listeners’ heads for all time as a member of Ornette Coleman’s epochal quartet. He’d also put his music where his progressive politics were as founder-leader of the Liberation Music Orchestra and burnished his reputation by helping enhance those of such diverse artists as Geri Allen, Kenny Barron, Hampton Hawes, Abbey Lincoln, Hank Jones, Paul Motian, Bley and Jarrett by sitting in or collaborating with them, live or on record. Whether you dug Haunted Heart or Always Say Goodbye depends on how much you happen to be into the same old movies that Haden was. And Haden’s affinity for Raymond Chandler and other SoCal literary lights was genuine enough to give added integrity and sturdiness to his dreamscapes. Unlike a lot of actual filmmakers, Haden didn’t see those crime melodramas as excuses for ironic reinvention or post-modern hijinks. He thought Chandler and his ilk were funny, incisive and, most of all, relevant enough for whatever present-day reality you inhabit. His perpetual sense of wonder with the sunset-infused landscape of modern jazz and tarnished dreams was infectious – and you were motivated as he seemed to be to imagine your own movies sequences to match the music.

The other Quartet West Verves – 1990’s Haunted Heart, 1993’s Always Say Goodbye, 1995’s Now is the Hour and 1999’s The Art of the Song – were more or less pastiches of movie soundtracks, vintage recordings by such diverse artists as Jo Stafford, Jeri Southern, Chet Baker, Billie Holiday, Duke Ellington, Coleman Hawkins and Django Reinhardt. (In the last entry, a full orchestra and singers Shirley Horn and Bill Henderson joined the quartet in the studio.) Critics were mostly enchanted with these discs when they were first released, even though you could hear grousing from some corners that Haden was squandering his considerable energies on studio gimmickry; a kind of “sampling” for nostalgic grownups. But Haden had earned wellsprings of credibility that began to collect around his name in the late 1950s when he’d helped rearrange the furniture in listeners’ heads for all time as a member of Ornette Coleman’s epochal quartet. He’d also put his music where his progressive politics were as founder-leader of the Liberation Music Orchestra and burnished his reputation by helping enhance those of such diverse artists as Geri Allen, Kenny Barron, Hampton Hawes, Abbey Lincoln, Hank Jones, Paul Motian, Bley and Jarrett by sitting in or collaborating with them, live or on record. Whether you dug Haunted Heart or Always Say Goodbye depends on how much you happen to be into the same old movies that Haden was. And Haden’s affinity for Raymond Chandler and other SoCal literary lights was genuine enough to give added integrity and sturdiness to his dreamscapes. Unlike a lot of actual filmmakers, Haden didn’t see those crime melodramas as excuses for ironic reinvention or post-modern hijinks. He thought Chandler and his ilk were funny, incisive and, most of all, relevant enough for whatever present-day reality you inhabit. His perpetual sense of wonder with the sunset-infused landscape of modern jazz and tarnished dreams was infectious – and you were motivated as he seemed to be to imagine your own movies sequences to match the music.  As fond as I am of the Quartet West discs, I’ve come to believe since his passing that Haden’s greatest achievement as a moviemaker-for-the-mind lies somewhere beyond its body of work. It took me a long time even to appreciate Beyond the Missouri Sky, Haden’s 1996 session with guitarist Pat Metheny as anything more than a decorative collection of spare, wide-open-spacey duets. I am now one with the eighth edition of The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings, which places Missouri Sky among its “Core Collection” rankings. Even as a studio artifact, this album handsomely rewards re-listening with its overdubs and harmonic tracks. Haden’s melodic tone on the bass achieves depth and richness that coax greater fluidity and fineness from Metheny’s playing. The landscapes they evoke have big skies and gilded shadows. The mind movies here are less rooted in genre and more reminiscent of Rohmer or Antonioni in an avuncular mood. The latter didn’t make Cinema Paradiso, but there are nonetheless two pieces from that movie’s soundtrack along with Henry Mancini’s poignant theme from Two for the Road. And it gets even more personal than usual here: Roy Acuff’s “The Precious Jewel,” the mountain folk song, “He’s Gone Away” and Haden’s haunting original hymn, “Spiritual” are clearly intended to be tributes to the bassist’s parents, with whom he’d performed bluegrass and country ballads on radio when he was a little boy. Beyond the Missouri Sky was the first thing I thought of playing when I’d heard he’d died – and the sun was actually setting by the time “Spiritual” had run its course. It was less a funereal experience than a healing one. And I suspect it wont be the last time it will help ease the sting of bad news. After all, the movies he made weren’t distractions. Charlie Haden intended for his music – all of it — to be of use. What else are Truth and Beauty for?

As fond as I am of the Quartet West discs, I’ve come to believe since his passing that Haden’s greatest achievement as a moviemaker-for-the-mind lies somewhere beyond its body of work. It took me a long time even to appreciate Beyond the Missouri Sky, Haden’s 1996 session with guitarist Pat Metheny as anything more than a decorative collection of spare, wide-open-spacey duets. I am now one with the eighth edition of The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings, which places Missouri Sky among its “Core Collection” rankings. Even as a studio artifact, this album handsomely rewards re-listening with its overdubs and harmonic tracks. Haden’s melodic tone on the bass achieves depth and richness that coax greater fluidity and fineness from Metheny’s playing. The landscapes they evoke have big skies and gilded shadows. The mind movies here are less rooted in genre and more reminiscent of Rohmer or Antonioni in an avuncular mood. The latter didn’t make Cinema Paradiso, but there are nonetheless two pieces from that movie’s soundtrack along with Henry Mancini’s poignant theme from Two for the Road. And it gets even more personal than usual here: Roy Acuff’s “The Precious Jewel,” the mountain folk song, “He’s Gone Away” and Haden’s haunting original hymn, “Spiritual” are clearly intended to be tributes to the bassist’s parents, with whom he’d performed bluegrass and country ballads on radio when he was a little boy. Beyond the Missouri Sky was the first thing I thought of playing when I’d heard he’d died – and the sun was actually setting by the time “Spiritual” had run its course. It was less a funereal experience than a healing one. And I suspect it wont be the last time it will help ease the sting of bad news. After all, the movies he made weren’t distractions. Charlie Haden intended for his music – all of it — to be of use. What else are Truth and Beauty for?