April 1st, 2021 — movie reviews

Just so we’re clear, movies aren’t dead, though multiplexes are likely dying. And that process was well underway before COVID-19 locked down the world.

We keep hearing that there’s light at the end of this tunnel we’ve been trudging through for a year. But keep in mind, whether immunized or not, that we’re still in a tunnel, even as I’m writing this. And whenever we all can safely stagger into this light-at-the-end, it’s going to take a while for us to get our cloistered senses re-adjusted. Things will at the very least look a lot different at the outset from how they did a year ago, the movie business being among the familiar institutions most conspicuously affected by a year of closures and strictly enforced re-openings here and there.

Of course, I too have missed going to movie theaters, even the ugliest, most utilitarian of them. No matter how big an HDTV screen you’re able to squeeze into your kitchen or bathroom, the experience of watching any moving picture, whether as intimate as Persona or as populated as Rear Window is nowhere near as immersive as sitting with strangers in even the narrowest darkened room. As with any other self-respecting cinephile, I regret what seems an irreversible decline in a kind of romantic, near-heroic age of moviegoing commemorated by Martin Scorsese during the past year. Streams and clouds are no longer alternatives to theater-going. They are now, pretty much, The Ball Game. Given the choice between figuring out logistics for going out to see a blockbuster or watch that blockbuster at your own convenience as soon as it “drops,” how many would rather pony up the baby-sitting money, root around for gas and parking expenses and line up single file for whatever dubiously packaged snack will adequately meet their needs and those of the kids tagging along?

But we’ll still have movie houses; better yet, all those repertory houses that were devoured by the multiplex could come back to life and restore the romance and adventure celebrated by Scorsese. If whatever’s left of the multiplexes still think they can make a go of it by including all kinds of other distractions – arcade games, dining, aerial acts, whatever – they’ll carry on and some may even thrive in such reinvention.

And the really good news, at least as far as I’m concerned, is that the Age of Clouds and Streams will better enable greater diversity of both product and producers. Studios will no longer have to wonder about whether certain scripts and stories are too “niche-ey” to reap theatrical profits worldwide. In other words, Black and other minority filmmakers will have more and better outlets to tell their stories and, through such exposure, may eventually be empowered enough to carry those stories into wider marketplaces.

But that’s all for later. For now, the movies are still trying to pick their way through a bewildering, anxious and altogether strange year that may someday be regarded as a transformative one. Whether the transformations are for better or worse won’t be settled or even suggested by this year’s Oscars that, whatever else you want to say about them, don’t look a whole lot like the Oscars of a decade or even a half-decade before

As always, projected winners are in bold face and, whenever necessary, a FWIW (For Whatever It’s Worth) disclaimer/appendix will follow.

Oh…and one more thing: if you’ve been annually wagering on my picks, please don’t do that this year because this year, as opposed to its predecessors, I expect to be wrong about most, if not all of these.

Best Picture

Judas and the Black Messiah

Mank

Minari

Nomadland

Promising Young Woman

Sound of Metal

The Father

The Trial of the Chicago 7

After all those serial film festival triumphs, rapturous reviews and probing inquiries into its up-to-the-minute-neo-Grapes-of-Wrath relevance (or lack thereof), Nomadland has become this season’s catch-all for smarty-pants revisionism. Critics and civilians alike seem to be groping for reasons to dislike or dismiss it, many of them insisting on greater detail or added socio-political content that the movie’s structure was never built to contain in the first place. Why? Who’s that helping? And aren’t we supposed to be smart enough to tease out such inferences on our own? What happened to the idea of making the audiences work even a little bit instead of the story doing all the work for them?

I still believe in Nomadland, even if I’m no longer certain the Academy does. But what kind of Academy vote will matter here? If it’s the same Academy that punched Green Book’s ticket two years ago, then Mank, The Father or Chicago 7, the closest things to “traditional” Oscar bait, will get this one. If it’s the Academy that gave Parasite its unprecedented near-sweep of a year ago, then Minari, Judas and, yes, Nomadland lead the pack. This leaves Sound of Metal and Promising Young Woman, both very dark in very different ways. If you think the Best Picture vote is the best reflection of an overall industry mood, then I’m going to presume here that the overall industry is both anxious and angry over what’s happened over the last twelve months, or four years, or whatever index you choose to use. The mordant humor of Promising Young Woman is, from this vantage point, best suited to ride that wave. If on the other hand events since January 20th are making Hollywood feel more hopeful than not, then any of the others could take this one home. As with just about every category on the board this year, nothing’s set in granite.

UPDATE (4/8/21): Is it plausible to imagine a world in which the in-your-face storytelling of The Trial of the Chicago 7 vanquishes the sublimities of Nomadland or even Minari (which would be my personal choice)? Doesn’t take much imagining, because that world has been with us for as far back as the 1940s when issue-oriented melodramas such as Gentlemen’s Agreement could prevail over David Lean’s Great Expectations. (A greater, if not necessarily bigger movie than either Lean’s Bridge Over the River Kwai or Lawrence of Arabia. ) It’s still anybody’s ballgame as far as I’m concerned. But somehow Aaron Sorkin’s look-back-in-anger over what happened to Fred Hampton in 1969 seems more of an industry crowd-pleaser (and prototypical Oscar-winning Best Picture) than, say, Shaka King’s angrier one.

Best Director

Chloe Zhao, Nomadland

David Fincher, Mank

Emerald Fennel, Promising Young Woman

Lee Issac Chung, Minari

Thomas Vinterberg, Another Round

Zhao’s ascension is as compelling and inspiring a story as her movie’s. Besides which, it’s past time for a woman-of-color to win one of these

Best Actor

Anthony Hopkins, The Father

Chadwick Boseman, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom

Gary Oldman, Mank

Riz Ahmed, Sound of Metal

Steven Yeun, Minari

There’s been some chatter, as the NSA likes to put it, over how Hopkins’ portrayal of an Alzheimer’s victim is so consummately good that voters may decide he deserves another one of these after all. But Old and New Hollywood, in whatever post-Millennium forms they assume, were deeply shaken by Boseman’s passing last August and his widow’s acceptance speech at the Globes was so startlingly beautiful and moving that voters would love a reprise.

FWIW: Since we’re here, would it be OK if we take a brief tour of Boseman’s (brief) life’s work to determine which of his roles would or should have gotten this award beforehand? We can eliminate Black Panther ‘s title role, even though he evinced a lot of star power in all the MCU movies where his character appeared. Of the historical figures Boseman brought to life, his portrayal of James Brown in 2014’s Get On Up is the one that was at once the most electrifying and credible, though the Jackie Robinson he played in 2013’s 42 was more complex and cogent than was generally acknowledged at the time. A few words, but no more than a few, should be submitted on behalf of his impressive star turn in the 2019 NYPD thriller, 21 Bridges. But what in many ways represented Boseman at his most magnetic was his scene-stealing performance in Spike Lee’s Da 5 Bloods as the charismatic, doomed patrol leader for which he richly deserved a Supporting Actor nomination – and, for that matter, the Oscar. Have I mentioned yet that this particular nomination is only his first? How could I have forgotten to mention that? Oh, and about 5 Bloods? Delroy Lindo was screwed.

Best Actress

Andra Day, The United States vs. Billie Holiday

Carey Mulligan, Promising Young Woman

Frances McDormand, Nomadland

Viola Davis, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom

Vanessa Kirby, Pieces of a Woman

In any other year, this might have been the occasion for yet another win for Academy fave McDormand. But this a formidable quintet competing in what is almost, but not quite, as wide open a contest as this year’s Supporting Actress race (see below). Early on, Day’s Golden Globe victory took so many by surprise that it compelled several hundred eyes to gaze upon her intuitively intelligent rendering of Billie Holiday. The rest of her movie, however, can’t keep up with her and, in some ways, drags her down. She could still take it. But Mulligan’s been poised for some time towards Oscar’s embrace the same way that a heat-seeking missile is poised to take down an enemy compound. And this all-out performance of a fierce, wounded feminist avenger, especially when juxtaposed with her un-nominated, but noteworthy turn as an emotionally-tough-yet-physically-fragile aristocrat in The Dig, seals Mulligan’s reputation for range and raw nerve.

Best Supporting Actor

Daniel Kaluuya, Judas and the Black Messiah

LaKeith Stanfield, Judas and the Black Messiah

Leslie Odom Jr., One Night in Miami

Paul Raci, Sound of Metal

Sacha Baron Cohen, The Trial of the Chicago 7

Yet another example of what should have been acknowledged as a lead performance that’s (kind of) a ringer in the supporting category. Some think having Stanfield in the mix make a cancelling-out effect, or even a tie, inevitable. Ties are not unprecedented, but it won’t happen here. And I’ve been hearing about “cancelling-out effects” for most of my adult life and now believe them to be as mythological as sports teams getting a championship for no other reason except that they’re “due.” Gambling tip: next time you hear somebody make a pronouncement like that, hook them immediately for whatever hard cash you can risk. And thank me later.

FWIW: If I had a vote, it’d go to Raci, without a second thought.

Best Supporting Actress

Amanda Seyfried, Mank

Maria Bakalova, Borat Subsequent Moviefilm

Glenn Close, Hillbilly Elegy

Olivia Coleman, The Father

Youn Yuh-jung, Minari

So wide open, as noted earlier, that there’s no such thing as a dumb guess here. Coleman’s recent win for The Favourite makes her the least likely winner. But as I’d warned the year she got that Best Actress prize, quite a lot of people love her and as noted above, The Father’s been picking up some momentum on the home stretch. Close’s work was, by common consent, the best thing about her movie and the Academy seems to be searching for some way, any way, to give her a win after eight tries. Bakalova’s turn as apprentice Kazakh journalist and would-be-sex-partner to Rudy Giuliani may have been the century’s most audacious comedic impersonation and she’s been getting considerable buzz for it. Seyfried already has amassed a great deal of industry-wide affection, and it’s hard to imagine an Oscar contender going away empty-handed after picking Gary Oldman’s pocket in a black-and-white movie in which Orson Welles is more of a supporting character than hers is. Except..in situations such as this, dark horses always have a chance. And since the marvelously bawdy and winsome Youn Yuh-jung has won the SAG, she’s no longer a dark horse. Nevertheless I insist it’s still wide-open.

Best Adapted Screenplay

Borat Subsequent Moviefilm

Nomadland

One Night in Miami

The Father

The White Tiger

Usually I go with the Writers. Guild on these, but I’m having trouble picturing the same crowd who put their heads together on Borat Subsequent Moviefilm converging here as one big winner, though it’d certainly be my preference. Kemp Powers is already assured of a win for co-directing Soul (see below). But he’s been such a conspicuously entertaining media presence throughout the Oscar campaign season that it isn’t hard to see him scoring a rare double here. Of course, if Nomadland gets a monster surge of momentum towards the home stretch, I’m an idiot once again.

Best Original Screenplay

Judas and the Black Messiah

Minari

Promising Young Woman

Sound of Metal

The Trial of the Chicago 7

Definitely going along with WGA on this one for its serrated edges and willful ingenuity. Dark as hell, almost literally speaking, but in its weird, deterministic way, the most fun of these assembled nominees. (I mean, not that “fun” has anything to do with it, but…)

Best International Feature

Another Round (Druk)

Better Days (Shaonian de ni)

Collective

Quo Vadis, Adia?

The Man Who Sold His Skin

Thomas Vinterberg’s Best Director nomination was about as big a “tell” as you can expect as to how this one’s going to go. But it’s also the closest Vinterberg has come to a “feel-good” movie and that will count for a great deal with the general consensus.

Best Documentary Feature

Collective

Crip Camp

My Octopus Teacher

The Mole Agent

Time

I took Crip Camp to my heart for how authoritative and touching it was in rendering the rise of the handicapped-rights movement. And this grizzled old newspaperman greatly appreciated Collective’s intricate, rousing examination of how investigative journalism can effect change, even in a government as corrupt as Romania’s. But Garrett Bradley’s multi-layered chronicle of a Black woman entrepreneur’s efforts to overcome heavily stacked odds in freeing her husband out from under an egregiously lengthy prison stretch is the most innovative picture among this year’s entire slate of feature films, fiction or nonfiction. This doesn’t necessarily mean it will win. But for those who still appreciate how movies can still catch you by surprise in the things they do (or don’t), it’s, so to speak, Time.

UPDATE (4/23/21): Way too late to take my hand off this piece, but the New York Times this morning has My Octopus Teacher the overwhelming favorite and I should’ve known it carried even more of a feel-good vibe than Time. I’m prepared to concede defeat on this one. My only comfort is that it won’t be the only one.

Best Animated Feature

A Shaun the Sheep Movie: Farmageddon

Onward

Over the Moon

Soul

WolfWalkers

A lay-up, of course. All the same, it’s a drag that Pixar releases one of its finest features the same year that the Ireland-based Cartoon Saloon gives cel painted animation a gratifying jolt with the enrapturing WolfWalkers. The jazz beaux and the romantic folklorist living within me are deeply divided — though I doubt either of them will grieve all that much if the Saloon scores the (unlikely) upset.

Best Cinematography

Judas and the Black Messiah (Sean Bobbitt)

Mank (Erik Messerschmidt)

News of the World (Darius Wolski)

Nomadland (Joshua James Richards)

The Trial of the Chicago 7 (Phedon Papamichael)

I don’t know who has the edge here, so I’m going to presume that what Messerschmidt does with shadows and light emit dazzle sufficient enough to carry the day.

FWIW: Of course, if Nomadland runs the table, etc etc.

Best Original Score

Da 5 Bloods (Terence Blanchard)

Mank (Trent Reznor & Atticus Ross)

Minari (Emile Mosseri)

News of the World (James Newton Howard)

Soul (Trent Reznor, Atticus Ross & Jon Baptiste)

Reznor and Ross’ only real competition here is with themselves and Stephen Colbert’s unflappable bandleader pushes this one over the hump with the kind of acoustic jazz charts the movies have hitherto forsaken.

Best Song

“Husavik” from Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga

“Fight for You” from Judas and the Black Messiah

“Speak Now” from One Night in Miami

“Io Se (Seen)” from The Life Ahead

“Hear My Voice” from The Trial of the Chicago 7

Leslie Odum Jr., the song’s co-writer and performer is compensated for not getting the Supporting Actor prize for re-enacting Sam Cooke. It must be nice….

December 18th, 2014 — movie reviews, on writing lit -- and unlit, TV reviews

Because I don’t have to, I’m not going to bother with a Top-Ten movie list this year. This is also because there wasn’t a whole lot I saw at the multiplexes in 2014 that got me as wound up as the stuff I’m listing below. And if I bothered to enumerate the movies that did, I’d likely end up with a list that more or less looks like everybody else’s, which precisely none of us wants.

Instead, I’m going to pull together a rag basket of items that for various reasons made the most resounding connections with my frontal lobes through the prevailing media din of weapons-grade white noise and free-styling schaudenfreude. Most came out this year; some didn’t, but I got around to them for the first time this year, so they count. (My list, my rules.)

Quite likely, I’m forgetting, or blocking some stuff. It’s been that kind of year. And there were some things I couldn’t bring myself to include, whatever my absorption level. Scandal, to take one example, remains for many people I trust an irresistible sack of Screaming Yellow Zonkers. But outside of Joe Morton’s righteously Shatner-esque scenery chewing and the mad electricity vibrating in Kerry Washington’s eyeballs, I’ve found that its live-action anime antics can go on without me for at least a couple weeks at a time.

So anyway…(as this fellow might out it)

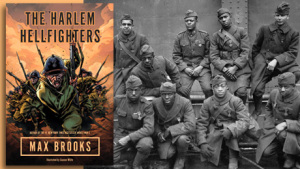

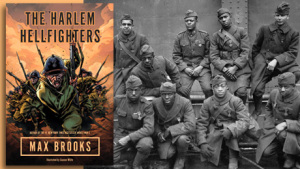

The Harlem Hellfighters by Max Brooks –Brooks made his name mythologizing the walking-dead (World War Z, The Zombie Survival Guide). But he proves himself just as conscientious in rendering factually grounded savagery in this fire-breathing graphic (in every sense) novel about the legendary all-black 369th Infantry Regiment that roared out of Harlem to fight in World War I, the hinge between post-Reconstruction’s legally-sanctioned terrorism of African Americans and the gathering pre-dawn of the civil rights movement. Though the Hellfighters’ passage from raw, often humiliated recruits to take-neither-prisoners-or-shit-from-anybody warriors is rousing, the visual depictions of squalor, disease and violence (thanks to the classic-war-comics élan of illustrator Canaan White) deepen the many ironies layered onto this saga; not the least of which was that it was only through the horrific, demeaning process of war that black men could begin proving their worthiness as American citizens – and even that wasn’t enough. To establish its own validity as historical fiction, Brooks’ account brings in such real-life badasses as James Reese Europe, Henry Lincoln Johnson and Henri Gouraud for colorful cameos. Of course, a movie is planned. Good luck trying to top this

Scarlett Johansson –I’ve already waxed rhapsodic about the commanding way she works the alien-enigmatic in the polarizing Under the Skin. By contrast, the art-house crowd showed relatively little-to-no-interest in Lucy in which she played a hapless, sponge-faced drug mule accidently injected with a drug transmuting her into a time-distorting, matter-altering, ass-kicking wonder woman. But Luc Besson’s acrylic pulp fantasy proved that few, if any movie actresses today are as cavalierly brilliant at throwing down wire-to-wire magnetism in such nutty eye candy. Manny Farber would have wallowed in the termite splendor of it all. Even her by-now borderline-gratuitous Black Widow turn in support of yet another Marvel money machine (Captain America: The Winter Soldier) retained enough droll slinkiness to make one suspect that giving the Widow her own vehicle might be a bit of a let-down. Then again, Ms. Scarlett never let me down once this year, so why dwell upon the purely speculative?

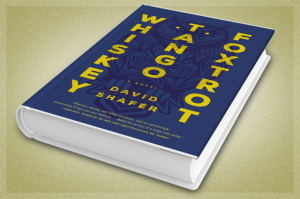

Whiskey Tango Foxtrot By David Shafer – This novel took me by surprise as it did several other critics this past summer. Up till that point, it hadn’t occurred to me that the legacies of both Richard Condon and Ross Thomas could, or even should be filled. Nevertheless, anyone whose familiarity with these authors’ works extends beyond Condon’s The Manchurian Candidate or Thomas’ The Fools In Town Are On Our Side will recognize Shafer’s sardonic humor, crafty plotting and humane characterizations as reminiscent of both authors – which is another way of saying these qualities aren’t what readers of contemporary techno-thrillers are used to. Also, much like Condon, Shafer knows, or strongly suspects, what we’re all afraid of, deep down, and finds a surrogate for this fear that’s both outrageous and plausible; in this case, a sinister cabal of one-percenters planning to seize total control of storing and transmitting information worldwide, thereby making recent abuses by the NSA, or whoever has it in for Sony Pictures, seem like benign neglect. This premise scrapes somewhat against territory controlled by what used to be called the “Cyberpunk School” as well as Thomas Pynchon, except that Shafer’s three 30-ish hero-protagonists are at once unlikely and recognizably human: an Iranian-American NCO operative who stumbles into the conspiracy so haphazardly she’s not sure what it is until it goes after her family, a self-loathing self-help guru in debt to his eyeballs who’s recruited by the cabal to be its “chief storyteller” and his estranged childhood friend, a substance-abusing misfit with a trust fund as thick as his psychiatric case file. They are all swept into an underground movement called “Dear Diary” which knows what the cabal is up to and is deploying its own secret network to bring it down. Social comedy, political melodrama and digital menace don’t always blend as well as they do here. And this is only Shafer’s first novel, meaning, as with the other masters cited above, he can only get better at this stuff from here on.

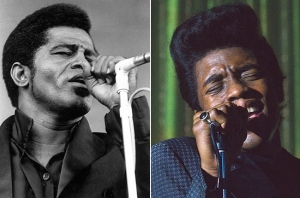

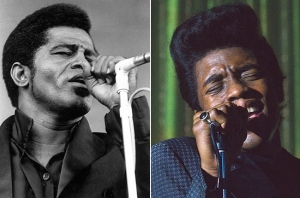

Get On Up & Mr. Dynamite: The Rise of James Brown – The former is a feature biopic; the latter an HBO-exhibited documentary. Both told me things I didn’t know about their shared subject – or, maybe more to the point, framing what I already knew about James Brown’s story in a manner that showed him as far more than an unholy force-of-nature. If I lean more towards the documentary, it’s because the revelations are more striking (not just the spectacular “what” of Brown’s showmanship, but the painstaking “how” of its components along with its savvy adjustments over time). And its testimonies are altogether more enlightening (Mick Jagger, who co-produced both, sets the record straight on how the “T.A.M.I. Show” sequence of acts really went down) I loved listening to band members let loose on what they really thought of their sometimes thoughtless boss as well as what second-generation Fabulous Flames as Bootsy Collins learned on and off the road from Brown. Tate Taylor’s biopic has a different agenda, but it strives to be just as faithful, if not always to the facts, to the facets of Brown’s fiery, hair-trigger temperament. Maybe it tried too hard. (As far as B.O. was concerned, Get On Up…didn’t.) But Chadwick Boseman’s, conscientious rendering of Brown’s tics and turbulence is almost as breathtaking to watch as one of the Godfather’s actual Soul Train appearances. Now that Boseman’s successfully portrayed two historic icons, I remain anxious to see what he can do with a Regular Guy role sometime between now and Marvel’s Black Panther movie.

FX– The third, and best, season of Veep; the harrowing, jaw-dropping single-take night scene in True Detective; Billy Crystal’s astute, heartwarming 700 Sundays; Girls and its discontents; the sheer how-can-it-possibly top-itself-again-and-again momentum of Game of Thrones…There was so much to love about HBO this year that I feel like an ingrate for professing my affection for a rival, even though there are things in both FX and HBO that I’ve neglected (American Horror Story, Boardwalk Empire) or shortchanged (The Strain, The Leftovers). Nonetheless anyplace I can find Louie, Archer, The Americans and (for me, especially) Justified is a cozy, stimulating home for my mind. Add to this the deep-dish pleasures of Fargo, whose greatness sneaked up on me the way Billy Bob Thornton’s meatiest, slimiest character since Bad Santa slithered through the frozen tundra, and of The Bridge, whose shrewd and nervy evolution from its first, somewhat derivative season went mostly unnoticed by the professional spectator classes and I’m not sure FX doesn’t have a deeper bench, pound for pound, than its bigger rivals., I prefer a lean, mean FX that takes so many worthy, edgy chances that it can be forgiven for something as lame and sad as Partners. (Never heard of it? Good. We shall speak no more.)

The Oxford American “Summer Music Issue” – I, along with many of my friends, have lots of reasons for being mad at the once-and-future Republic of Texas. But I still love its literary heritage and, most especially, its thick, spicy blend of home-grown music, which takes up C&W, R&B, Tex-Mex, swing, funk, hip-hop and even some avant-garde jazz courtesy of native son Ornette Coleman. They’re all represented on a disc accompanying a special edition of this always mind-expanding quarterly. Compiled by Rick Clark, this CD provides the kind of kicks your smarter buds used to slap together on cassette as a stocking stuffer. Besides the aforementioned Ornette (“Ramblin’”), there’s some solo Buddy Holly (“You’re the One”), early Freddy Fender (“Paloma Querida”), priceless Ray Price (“A Girl in the Night”) and the unavoidable Kinky Friedman (“We Reserve the Right to Refuse Service to You”). The left-field surprises include an especially noir-ish take of Waylon Jennings doing his signature “Just To Satisfy You,” a deep-blue rendition of “Sittin’ On Top of the World” by none other than Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys, Ruthie Foster’s espresso-laden performance of “Death Came a-Knockin’” and Port Arthur’s own Janis Joplin fronting Big Brother and The Holding Company on a “Bye, Bye, Baby” that swings as sweet as Julio Franco once did. I don’t want to shortchange the actual magazine, which includes James Bigboy Medlin’s reminiscences of working with Doug Sahm, Tamara Saviano’s portrait of Guy Clark and Joe Nick Patoski’s story about Paul English, Willie Nelson’s longtime drummer. It doesn’t beat a spring-break bar tour of Austin, but it’ll do until I get a real one someday.

April 16th, 2013 — movie reviews

If you retold Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by moving it several hundred miles upriver, replacing Huck with an older, craftier version of his friend Tom Sawyer and making Jim a younger, more articulate family man, you might well have the true-life, mid-20th-century’s Greatest Story Ever Told: How Branch Rickey and Jackie Robinson engaged on a perilous two-man odyssey to force racial integration down major-league baseball’s throat and make America like it. The difference being that Huck, in refusing to turn Jim over to slave hunters, only thought he was going to hell. Jackie Robinson, throughout that trailblazing 1947 season of triumph and torment (mostly the latter), came as close to an earthbound purgatory as any mortal should have endured.

It’s a story that, much like Huck’s, never loses its power to simultaneously unsettle and inspire. And as with Twain’s masterpiece, no feature film could adequately do it justice, though at least one, The Jackie Robinson Story (1950), made a crude, earnest attempt with the genuine article sportingly, if woodenly, starring as himself. (It’s still interesting to see as a curio of its time and for watching two of our greatest actresses, Ruby Dee and Louise Beavers, on-screen even if they’re only playing silhouettes of Robinson’s real-life wife and mother respectively.)

42, the freshest rendition of the Jackie Robinson parable, is shinier and more authentic than its predecessor – which doesn’t mean it’s any less earnest or doggedly elemental in its execution. I would have no trouble whatsoever exposing a young girl or boy to Brian Helgeland’s digitally enhanced diorama. (It should probably come with one of those labels Milton Bradley used to put on its board-game boxes saying, “Ages 7-14.”) As Robinson, Chadwick Boseman emits the same smoldering intensity as the genuine article while suggesting, at times, some of the prickly-heat feistiness the major leagues would see once he no longer had to turn the other cheek. His scenes with Nicole Beharie as Rachel Robinson have a genuine ardor and unassuming sweetness rare in any movie with an African-American romantic couple. I’d be tempted to say it was a breakthrough for black movies if I thought the movie was all about them. And it isn’t.

For what the story of Jackie Robinson’s trial-by-fire has by now become (in ways that Huckleberry Finn never could) is an occasion for America in general and white people in particular to congratulate themselves on their capacity for change. Boseman’s Robinson may have more dimensions than the version Robinson himself enacted sixty-something years ago. But he is still less a fully fleshed character than a stoic presence, sustaining unspeakable punishment for his country’s sins. This doesn’t in any way mitigate his heroism or importance. But much as America’s astronauts, however fearless, were basically instruments of their country’s scientific and political will, Robinson was the instrument of one man’s far-sighted vision – and determination to overcome his own shame for his beloved game’s racial myopia .

We’re talking, of course, about Branch Rickey, 42’s true protagonist, the man who pulled the strings for this “great experiment” and made sure none of them were clipped. There sometimes seemed almost as many leading men in Hollywood yearning to play Rickey as there were wanting to play Chet Baker, though a far more motley group in the latter queue. Harrison Ford makes the most of his rare opportunity to go big, broad and hard. I hear some gripes about Ford going too far over the top – which discloses nothing so much as the complainers’ ignorance of baseball history. Outside of, say, Bill Veeck, Larry McPhail and George Steinbrenner, Branch Rickey is the only baseball executive whose larger-than-life presence is worthy of a movie. If anything, Ford seems at times a little too conscious of Rickey’s many facets (which, in Red Smith’s immortal turn-of-phrase, were all turned on). But it’s such an endearing performance throughout that you even enjoy Ford’s straining to get it just right.

The rest of the actors pretty much carry out their roles in this parable as expected, though history would have been better served by showing that Philadelphia Phillies manager Ben Chapman (the admirable, under-appreciated Alan Tudyk) wasn’t the only one in that team’s dugout ragging Robinson so viciously. (The late Richie Ashburn was one of the few players on that team in that era who owned up to such taunting and expressed his deep regret for it.) Poor old Dixie Walker (Ryan Merriman) must once again be properly humiliated for trying to whip up his white Dodger teammates in opposition to Robinson – though in later years, he pleaded for forgiveness from the press and public. As for Christopher Meloni’s Leo Durocher, he’s such a magnetically funny and vividly rendered character in his precious few moments onscreen that when he’s compelled to leave the team (and the movie), you wish you could follow him out the locker room door to watch what happens to him – and, of course, Laraine Day (Jud Tylor). There’s another movie waiting to be made, and if they’re smart, they’ll let Meloni continue in the role.

As for 42, it may not cut as deep as most of us would like. But it may say something about my own diminished expectations of Hollywood that I doubt we’re going to get a better movie version of this story for some time to come. Dioramas and comic books are what sell in the multiplexes these days and as long as the outlines and colors are reasonably aligned and the proper emotions are aroused, then I’m willing to settle for harmlessness as a virtue; just as long as nobody tries to sell 42 as genuine progress. Popular culture as a whole still can’t accommodate the complexity of a real-life Jackie Robinson who in the years since his arduous rookie season was fueled by unceasing rage and uncompromising passion for justice. Indeed, Hollywood movies in general still can’t adequately deal with emotional complexity of any kind — and may have stopped trying.