July 5th, 2018 — jazz reviews

John Coltrane will have been with the ancestors for fifty-one years this month. Yet he remains jazz’s toughest act to follow. Many people, not all of them fans, insist that jazz history stopped moving when Coltrane’s heart stopped beating in a Long Island hospital on July 17, 1967. Even those who were mystified, if not altogether alienated by Coltrane’s headlong voyages beyond the stratospheric boundaries of tone and invention acknowledged him as a bellwether for whatever would happen next for the music. His death at just 40 years old seemed to signal that there would be no more “next,” only whatever happened before.

So it’s hardly a wonder that a large crowd gathers whenever somebody uncovers Coltrane music that nobody’s heard on record before. They all swarmed four years before when a 1966 concert of Coltrane’s second, most experimental quartet was packaged and released to the public as Offering: Live at Temple University (Impulse!/Resonance). Though it was unavailable for digital downloads, Offering was at or near the top of the Billboard jazz charts for several weeks. My guess is that a majority of those purchasers were just as confounded by the music at that concert as they were by such late-period Coltrane LPs as Kulu Sé Mama, Expression, Meditations and Interstellar Space (about which more later). But its success affirmed what now seems an everlasting attraction to John Coltrane as karmic messenger; it’s as though we’ve all agreed that somewhere in Trane’s legacy there’s something we’re missing and we need only pay close attention when another such discovery is made.

Hence the buzz and jubilation surrounding this month’s release of Both Directions At Once: The Lost Album (Impulse!). These are never-before-released recordings of a March 6, 1963 studio session with Coltrane and his “classic quartet” of pianist McCoy Tyner, drummer Elvin Jones and bassist Jimmy Garrison. The set, recorded at Rudy Van Gelder’s legendary studio in Englewood Cliffs, N.J., includes several takes of Coltrane’s “Impressions,” the standard he’d built using the same harmonic baseline as Miles Davis’ “So What” on 1959’s epoch-making Kind of Blue. (Ashley Kahn’s typically informative liner notes mention that Trane himself wrote “So What” on the box holding the “Impressions” tapes.) There’s also a three-minute-plus take on “Nature Boy” and a couple of versions of “One Up, One Down” (not to be confused with “One Down, One Up,” which the quartet delivered with stunning abandon in a February1965 live broadcast at the Half Note previously released as part of a 2005 bootleg).

To me, the most fascinating of this “found” album’s storylines involves “Untitled Original 11386” (again, not to be confused with “Untitled Original 11383,” a hard-driving blues piece that opens the two-disc package and isn’t heard from again, even though you wish you could). It’s one of the quartet’s more buoyant riff extensions and it exemplifies the principal pleasure offered by this release: Listening to each member of this exemplary group interact, enhance and add to each other’s contribution whether it’s Jones’ loping and rolling combinations (especially when it’s just his trap set and Trane’s soprano doing a pas de deux), Tyner’s unobtrusive, yet bracing comps and Garrison’s sleek, powerful lines. Not that anybody needed to be reminded of this quartet’s pre-eminence above all others in its time, but even the minor glories of this session seem especially portentous given what would from this point on prove to be the group’s most productive and illuminating period (the Johnny Hartman sessions were a day away, the Birdland performances would be recorded in just seven months and the following year would yield the near-blinding sunburst that was A Love Supreme.)

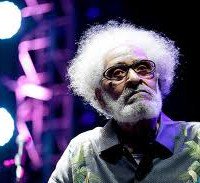

Sonny Rollins’ vivid encomium for this package, “This is like finding a new room in the great pyramid,” encapsulates every fan’s enthusiasm for Both Directions At Once. Still, while it’s only proper to have Rollins’ benediction on such an auspicious occasion and though I yield to no human in my devotion to the Colossus, I don’t think there are any startling discoveries to be found here regarding Coltrane’s genius. Beyond the renewed appreciation for the workaday brilliance of the quartet, of which there can never be enough examples (and is, by itself, no small virtue), I think the revelations of this disc have less to do with Trane and more to do with how jazz music used to produce both accessibility and adventure with both assurance and fortitude. The modal innovations pioneered and expanded by Coltrane have become so commonplace in jazz that it becomes easy to forget how exhilarating and easy to love its themes were.

Moreover, I think that when many listeners, whether jazz aficionados or not, embrace this music, they are consciously or not cleaving to a moment in time just before Coltrane decided to accelerate his inquiries into deeper, wider possibilities. Put less charitably, it’s at or near the spot where even the most devoted and forbearing listeners said “Adios” to Trane as he soared headlong into what they believed were impenetrable regions of tonal and rhythmic chaos.

So while I’m hoping that this “lost album” re-galvanizes the faithful while indoctrinating new generations to this quartet’s glories, I’d also commend all these listeners to use this occasion to slide over to where Coltrane began to press the edges of the envelope. I’m referring to 1965’s Ascension, the polyphonic freeform ensemble piece that joins Coltrane, Jones, Tyner and Garrison with such avatars of what used to be called “The New Thing” as saxophonists Archie Shepp, Pharoah Sanders, Marion Brown, John Tchicai and the enigmatic trumpeter Dewey Johnson, who played alongside Freddie Hubbard here and never recorded again. Those non-indoctrinated or hostile to free jazz hear nothing but random chaos in this piece. But if you pay attention from the start, you find that the whole sprawling, intermittently surging work can be viewed as the picaresque adventures of a five-note phrase – well, four notes actually since one of them is repeated. But try to keep up with that phrase throughout and you may find that while the whole apparatus seems to take you all over the place, it can also keep you centered in surprising ways. Which I’ve always suspected were Coltrane’s intentions all along.

If that trip seems in any way fruitful, then I’d recommend you jump ahead several albums and two more years to Interstellar Space, released by Impulse a year after Coltrane’s death and which has thus been called “the final masterpiece” by The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings. This is by no means a consensus opinion, given the many listeners who can’t get past the wailing, keening tone of Coltrane’s tenor in the first few bars of “Mars” as he and drummer Rashid Ali detonate their five-piece cosmic duet. But what some view as run-amuck obscurity, I prefer to accept as an act of willed ecstasy, a release from any obvious constraints of space and time (in the musical sense) and a daring leap towards a more organic means of fashioning unity in sound and meaning.

Some believe that “getting” such music requires sticking your head as close to the speakers as you can until its “meaning” materializes in front of you. That’s almost the right idea, but as I’ve suggested before in other contexts, I think you’re better off carrying the music with you and allow it to blend in with the other more inchoate sounds in your life. That’s how I “got” it – or more to the point, appreciated it.

Another suggestion: After letting these “Interstellar” sounds live in you for a while, go back to Both Directions At Once. And yes: there’s a hint of an explanation to All Things Trane in that title, but you’ll have to finish the rest of the course on your own.

December 4th, 2014 — jazz reviews

A strange year, an exasperating year; maybe even an ominous one for jazz music’s already diminished stature in the marketplace. First this happened, followed closely by this. And then this came up and so did all the resulting cawing and cackling on the social media sites. When you add the very public, free-falling disgrace of the nation’s leading — or, at the very least, most famous — jazz devotee, you may as well shrink wrap and label 2014 as a bummer despite the varied finery listed below.

And I know what you saner, stoic ones are going to say: That a list such as mine, or anyone else’s, represents the best possible counterargument to the signifying-nothing that is sound-and-fury, on- or offline. Art doesn’t care what the Washington Post or New Yorker says or does – or mostly doesn’t. Art walks its own serene path through the fire towards high ground. Art is a ninja-warrior aristocrat with two layers of body armor and an unrelenting poker face. Art would assure me, in firm, modulated timbres, that just because some people think jazz stopped being cool doesn’t mean it has.

Knowing all that, however, doesn’t improve my end-of-the-year mood; one that can’t be quantified as good or bad, but is, all at once, restless, melancholy, somewhat manic and predominantly wary. All told, I’m just a little anxious to see what’s coming next – in jazz and everywhere else.

You ask: Dread or hope? I say: Turtles are cool.

1.) Ambrose Akinmusire, “The Imagined Savior is Far Easier To Paint” (Blue Note) – As with its illustrious Blue Note predecessors from fifty years ago, Akinmusire’s second effort for the label meshes with the subconscious fabric of its turbulent times without needing to be explicit in its content (except when it chooses to do so). Just as Donald Byrd’s “A New Perspective,” which brought this into the world, is still redolent of all that America was going through in the early sixties, so do the somber, mostly minor-key soundscapes in “The Imagined Savior…” reflect present-day sorrow, regret and barely-contained anger with thwarted possibilities. The anger breaks into full, unfettered view in the sepulchral “Rollcall for Those Absent” on which the voice of young Muna Blake, backed only by Akinmusire’s keyboard and Sam Harris’ Mellotron is heard reading the names of young black men shot to death by police, including Amadou Diallo and Trayvon Martin, whose names are intoned more than once. That more names could have been added to this roll since it was recorded only enhances the disc’s up-to-the-minute capital. Adding to this Tapestry of Now is “Our Basement (ed)”, written and sung by Becca Stevens, which is told from the perspective of a homeless man. What counters the ruminative gloom and anxiety of these and other pieces is the vigorous musicianship displayed by Akinmusire as both trumpeter and bandleader. In both capacities, he has a fluid command of phrase that comes across the way electricity would if you could hold it in your hands. Whether letting fly with his regular combo, including front-line partner Walter Smith on tenor sax, or blending with a string quartet, Akinmusire’s horn reaches for and often achieves attributes of the human voice, a quality that clearly marks him as one with all the greats on his instrument who preceded him. If you wonder (as my erstwhile colleague and friend A.O. Scott does) if there are artists who can speak directly and indirectly to the Way We Live Now, look in this corner of the room and get to know its dimensions. Be advised: They can only get bigger from here on.

2.) Allen Lowe, “Mulatto Radio: Field Recordings 1-4 (or: A Jew At Large in the Minstrel Diaspora”)(Constant Sorrow 101) – In the 32-page liner notes accompanying this package, which constitute some of the finest music criticism I’ve read all year, Lowe begins by talking about his “strange encounter” with fellow classicist/bandleader Wynton Marsalis, with whom he dared discuss “the modernist implications of minstrelsy,” which Marsalis pointedly refused to engage since he’s predisposed to regard hip-hop in general and ”Gangsta Rap” in particular as “neo-minstrelsy” catering to racial stereotypes. Which was far from the point that Lowe was attempting to make in the first place. In the six years since that brush-off, Lowe, a polymath who’s as incisive with his shtick as he is with his sax, dove headfirst into what some would consider the mongrelized, or creole-lized foundation of 20th century popular music where shotgun-shack juke joints and free-swinging black vernacular found communion with the tunesmiths piecing together their slick contraptions on Tin Pan Alley, or in the Brill Building. The result of Lowe’s restless search for a proper response to Marsalis is this four-disc omnibus of mostly home-cooked sessions (Lowe lives in Maine) in which several traditions – gutbucket, gospel, early New Orleans, ragtime, bebop, stride, avant-garde, nightclub swing, noir soundtrack, beat poetry and backwoods country – are probed, prodded and often pulled inside out (so to speak) with an eclectic array of musicians from saxophonist J.D. Allen, trumpeter Randy Sandke and clarinetist Ken Peplowski to saxophonist Noel Preminger, pianist Matthew Shipp and singer Dean Bowman. Along with other reeds, horns and rhythm players, there’s also a tuba (Christopher Meeder), a fellow musicologist (Lewis Porter) who plays wicked piano, alone or accompanied, and – of course, what else? – a novelist (Rick Moody). Even some of the titles of these pieces – “Jim Crow Variations”, “The Discreet Charm of the Underclass,” “When My Alarm Clock Rings on Central Park West” (Lowe’s variation of “When it’s Sleepy Time Down South”) – are provocative, mischievous throw-downs to whatever passes these days for dialogue about jazz. And after a year such as this, the prevailing conversation can use some spritzing and shaking-up. (Don’t try to get this through Amazon or I-Tunes. You’re better off ordering it this way.)

3.) Sonny Rollins, “Road Shows: Volume 3” (Okeh/Doxy)— I’m well aware that we who worship at the Altar of the Colossus often get carried away. My own effusions are tempered by what a fellow patron said about the GLTS (Greatest Living Tenor Saxophonist): that he’s a lot like Mickey Mantle because their strikeouts can be just as spectacular as their home runs. Still, you have to believe me when I tell you that this third installment of recent live Rollins feels richer, goes deeper and is altogether more rewarding than its predecessors. And I say this as somebody who tried, at first, to distract myself from its lure by doing…well I don’t remember exactly. But I do remember feeling my head swivel sharply upon hearing Rollins’ variations on “Someday I’ll Find You,” the album’s second track, from a 2006 performance in Toulouse. This Noel Coward ballad begs to be crooned in the grandest of tenor styles. Rollins never croons, at least not here. He asserts the theme while veering ever so modestly off its edges to let you know what’s coming as soon as he retrieves center stage from guitarist Bobby Broom. When it’s his turn to speak, Rollins slides into the first bars of the melody, pulling at its corners before he really gets to work somewhere around the third chorus. (Or is it the fourth? Never mind.) He’s clearing away open spaces for whatever direction he wants to go. At one point, he’s playing with the harmonies in the grand modernist manner of pulling them apart and rearranging them in different patters; maybe he’ll become fond of a riff and run with it to see if it opens still more territory, making just enough room for one of his licks to leap into the sky if only so he can find out where it lands. He’s trying to figure it all out as hard as we are. That’s why we’ve borne witness all these years: To collaborate in his process and share his potential surprise with what’s disclosed. There’s plenty more enlightenment to be found on these arias. And, jumping back a couple metaphors, there’s not a strikeout in the bunch.

4.) Kenny Barron & Dave Holland, “The Art of Conversation” (Blue Note) – Barron has proven to be such a compelling partner in previous recorded colloquies with Stan Getz, Charlie Haden and Regina Carter that it’s a wonder it’s taken this long for him to have a sustained sit-down with the indefatigable Mr. H. To say their meeting doesn’t disappoint would be understating matters to a felonious degree. They engage in an organic, mutually respectful flow of ideas and storylines with each man giving leeway to the other seemingly by intuition more than design. They hit all the lights on such standards as Parker’s “Segment” (which, for this occasion, should have worn its alternate title, “Diversity”), Monk’s “In Walked Bud” and, especially, Strayhorn’s “Daydream.” The revelations are more pronounced when it comes to each player’s compositions: Barron’s “Rain” opens vistas of lyrical expression for Holland while the latter’s “Dr. Do Right” craftily indulges Barron’s affinity for the Latin beat. I’m especially partial to the opening track, Holland’s “The Oracle,” because it is so reminiscent of one of my all-time favorite trio albums of the same name led by the late great Hank Jones and featuring Holland and the also-now-departed Billy Higgins. That album is out of print. This one more than compensates for its absence.

5.) Marc Ribot Trio, “Live at the Village Vanguard” (PI) – I have for decades challenged those who love hard rock, but hate progressive jazz to imagine, when listening to an outer-limits tenor sax solo, that there’s an electric guitar laying down the same pipe. I’ve urged jazz heads to do the reverse for heavy-metal speed runs. No takers at either end. But who’s going to listen to me anyway? Better that they should all listen to this, because when guitarist Ribot, drummer Chad Taylor and bassist Henry Grimes Go Outside as did John Coltrane (“Dearly Beloved,” “Sun Ship”) and Albert Ayler (“The Wizard,” “Bells”), they don’t merely make my point. They drive it home like a high-performance car going down on a steep hill at top speed. This unit’s been mining such territory for some time now and the revelations burn hotter within the hallowed confines of jazz’s Holy Dive. Oddly enough, though, it’s when Ribot and company do a 180 and apply their eclectic chops to light-footed, more conventional renditions of “Old Man River” and “I’m Confessin’ (That I Love You)” that they really seem to be taking chances; each man carefully spreading their range onto these chestnuts without unnecessary spillage. Their solicitousness within the body of each song gives greater magnitude to what they do outside the lines. Just to re-emphasize: Anything that’s done to amplify the enigmatic, yet persevering legacy of Grimes’ old boss Albert Ayler is worth the investment of energy; theirs, and yours.

6.) David Weiss, “When Words Fail” (Motema) – Most of the music here is so buoyant and luminous that you would never guess that the project is haunted by sadness and loss. Trumpeter Weiss, whose myriad activities include leadership of The Cookers, a septet formed in tribute to Freddie Hubbard, composed most of the pieces on this disc and writes in the liner notes of a full year of sudden, deepening tragedy beginning with the death of seven-year-old Ana Grace Marquez Greene, daughter of saxophonist Jimmy Greene, in the December, 2012 Sandy Hook School massacre. The father of the Motema label’s founder passed away during the ensuing year as did such jazz luminaries as Jim Hall, Donald Byrd, Mulgrew Miller, Butch Morris, George Duke and Cedar Walton. And just weeks after this session was completed, its bassist Dwayne Burro, died from pneumonia. The title track, named for the beginning of a Hans Christian Anderson quote that ends with “music speaks,” is dedicated to Burro while “Passage Into Eternity” was written with the Greene family in mind.. Here and elsewhere, you expect something somber and funereal, but instead find lively, propulsive small-group jazz that gives off warmth while staying resolutely cool. When the world keeps saying, “No,” music as joyfully rendered as this insists on saying, “Yes.”

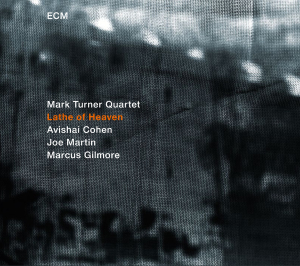

7.) Mark Turner Quartet, “Lathe of Heaven” (ECM)— Somewhere in the alchemic Ursula K. Le Guin novel that gives this disc its title, there’s a quote from Victor Hugo that describes dreaming as “nothing other than the approach of an invisible reality.” As with the book, much of the music on this album, Turner’s first as a leader in 13 years, shifts time and space while somehow remaining self-contained and grounded. Not since the passing of Joe Henderson has there been a narrative artist on tenor saxophone such as Turner, who, as with Henderson, makes his statements through stealth, cunning and patience, his phrases cohering into shapes that are at once familiar and esoteric. He finds in trumpeter Avishai Cohen a worthy harmonic partner in thematic expression; Cohen bringing a fiery, full-bodied tone to compliment Turner’s cool, dry musings. The overall pace seems locked in neutral, the better to allow the mercurial front line to simulate invisible realities, though the rhythm section of bassist Joe Martin and, especially, drummer Marcus Gilmore execute throughout a slipstream swing compatible with weaving dreams. You couldn’t call this a comeback since Turner’s been quite busy in many venues and combos. But having him return out front, so to speak, affirms the hopes he inspired a decade-and-a-half ago as a tenor player skating to a softer drumbeat.

8.) Steve Lehman Octet, “Mise en Abime” (PI) – Though not packaged as such, Lehman’s latest series of experiments in sound mosaics represents a kind of deep-space 90th birthday party for Bud Powell, given that at least two of the tormented bop genius’s pieces, “Glass Enclosure” and “Parisian Thoroughfare,” are so drastically reinvented as to be barely recognizable, except for the angular dynamics Lehman applies to their abstract designs. Because his intellectual qualifications are part of Lehman’s hype, you’re tempted to think of his work as composer, arranger and altoist in purely cerebral terms. But given his all-star lineup of some of the brightest young players (trumpeter Jonathan Finlayson, trombonist Tim Albright, saxophonist Mark Shim vibraphonist Chris Dingman and drummer Tyshawn Sorey among others), Lehman has too much firepower at his disposal to leave listeners on ice, so to speak. He’s so creative in his harmonic combinations and electronic enhancements that I’m a little curious to see what he does in more specified contexts; Christmas, say, or 1940s rhythm-and-blues, or the Sun Ra Songbook.

9.) Matt Wilson Quartet with John Medeski, “Gathering Call” (Palmetto) – I’ll just repeat what I posted back in January since a whole lot’s happened since then: Hard bop, late-1960s/early 1970s vintage, played without apologies and with an open-hearted joie de vivre that can make even the hardest of hard-core progressives wonder why they ever thought the genre was old news. I suppose some would still think it old news, even if they liked it. But there’s nothing musty or creaky about Wilson’s easygoing command of the trap set in all situations or his group’s saucy renditions of such Ellingtonia as “Main Stem” or “You Dirty Dog.” The quartet also pays homage to the recently departed bassist Butch Warren by playing the latter’s “Barack Obama” with the delicacy, wonder and cautious optimism you suspect the composer had in mind as he wrote it. You’re happy for the leader, one of the perennial Good Guys in the jazz business, which in turn makes you hopeful for the business itself.

10.) The Microscopic Septet, “Manhattan Moonrise”(Cuneiform) — Where in their 1980s flowering they suggested, as a perspicacious observer put it, a “wedding band from Mars,” these wily retro sharpies now look on the inside-cover photos of this disc like a weathered, motley council of wizards from a Tolkien homage hiding out from Sauron on a band bus touring the Dakotas in the winter of 1939. Yet even with added snow in some of their membership’s facial hair, the Micros still sound airtight, agile and ready for anything co-founders Joel Forrester and Philip Johnston toss into their playpen, whether it’s a funk stomp a la Johnston’s “Obeying the Chemicals,” a Monk-ish pastiche from Forrester, “A Snapshot of the Soul” or the snap-brim eminently danceable swinger, also from Forrester, that gives the disc its title. Cards on the table, I’m at a loss to explain what “MM” by TMS is doing here since it doesn’t exactly break new ground either for the group or for its genre. But it’s a genre that they, and they alone, own: Microscopic Septet music at its most proficient, inquisitive and enjoyable. There may have been more significant and ambitious albums I heard or missed out on this year, but few that had as much trouble staying out of my machines as this. Long Live The Micros! And Long Live Jazz – whatever the heck that means!

HONORABLE MENTION: “Frank Kimbrough Quartet” (Palmetto); Tyshawn Sorey, “Alloy” (PI); Regina Carter, “Southern Comfort” (Masterworks ); Omer Avital, “New Song” (Motema); Ron Miles, “Circuit Rider” (Enja); Keith Jarrett & Charlie Haden, “Last Dance” (ECM); Randy Ingram, “Sky/Lift” (Sunnyside); Jason Jackson, “Inspiration” (Jack & Hill); Matthew Shipp, “I’ve Been To Many Places” (Thirsty Ear); Richard Galliano, “Sentimentale” (Resonance); Aaron Goldberg, “The Now” (Sunnyside).

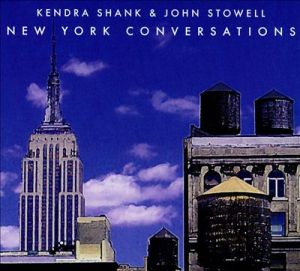

BEST VOCAL ALBUM: Kendra Shank and John Stowell, “New York Conversations” (TCB)

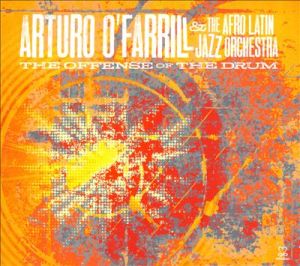

BEST LATIN ALBUM: Arturo O’Farrill & the Afro-Latin Jazz

Orchestra, “The Offense of the Drum” (Motema)

BEST REISSUE: John Coltrane, “Offering: Live at Temple University” (Impulse!)

HONORABLE MENTION: Charles Lloyd, “Manhattan Stories” (Resonance)

August 7th, 2014 — jazz reviews

Back in the winter of 1993, I threw a newsroom tantrum over an article that appeared in Spy magazine under the title, “Admit It. Jazz Sucks.” Written by Joe Queenan, then riding the ascending curve as a go-to contrarian crank for major media outlets, the piece was a mordant rant against what he perceived as a stuffed-shirt conspiracy to shove jazz music down the zeitgeist’s collective throat.

Most readers, even those unsympathetic to Queenan’s sentiments (and no, he wasn’t kidding about those), found it relatively easy back then to take the whole thing as bilious faux-regular-guy philistinism and move on with their lives. But I’d come across this screed at a time when I was still struggling to convince my New York Newsday editors that jazz music deserved a broader, bigger regular presence in its pages. The last thing I needed to hear from a national magazine, ANY national magazine, was a brash, loud voice suggesting to the editors that, well, yeah, maybe we don’t need to deal with this intimidating, complicated, provocative music that isn’t even as popular as it used to be. In other words, I took the damn thing personally – and stomped my feet, bellowed out loud, pounded furniture, etc. to let everybody I worked for, and with, know of my purple-cheeked displeasure.

And another thing: How exactly did Queenan figure that jazz was this domineering entity imposing itself upon whatever culture he believed himself to represent? If anything, jazz was catching more hell from the mainstream than it was receiving. Why the hell didn’t Spy magazine pick on somebody/something its own size? On top of everything else, it wasn’t even funny. Or smart. Even one of my editors, a rock-and-roller who like to bait me with similar anti-jazz bombs, thought the piece was lame –and, therefore, not worth getting ulcers over.

Indeed, after I’d calmed down and realized that I was all alone not just in detesting, but even caring much about the piece, it occurred to me that the very lack of furor generated by the article was dismal proof that even if Queenan was right about this conspiracy, it was already failing.

So life did in fact go on: Spy eventually folded. Queenan wrote better, if more bilious pieces. Newsday ended its noble New York City-based experiment. And jazz still came out at the other end of the century barely breaking even in the music marketplace. So all I can say to all my friends and fellow-travelers in the jazz universe who’ve been seething since last week over what I’ve come to know as the “Unfunny Sonny” blog on The New Yorker’s web site is this: I been there already.

Briefly, for the rest of you: About a week ago (though it seems longer), a piece began circulating on the web under the New Yorker’s aegis under the title, “Sonny Rollins: In His Own Words.” Only it sure didn’t sound like Sonny Rollins; more like a whiny savant who likened the sound of a saxophone to a “scared pig” and doesn’t see the point of jazz and hates his whole life. “If I could do it all over again, I’d probably be a process server or an accountant. They make good money.” You get the idea. If you don’t, here’s the rest of it.

It now sounds weird, but more than a few people who first came across this thing on social media sites actually thought that this was Rollins’ voice. (I recall one musician first reacted by thinking that this outburst was the result of Rollins playing for too long with substandard backup musicians. Which was almost as funny – or not – as the piece itself.) As the civilized world now knows, a senior writer for The Onion named Django Gold wrote it and, as you’ll now notice, the blog now comes with disclaimers. Why? Partly because of this loud, resounding, universal outcry from the jazz musicians, fans and journalists that, collectively, made my office tantrum of twenty-one whole years ago seem like a sneeze in a noisy stadium. (By the way, after reading Gold’s piece again, make sure you watch this afterwards if only to make clearer whose voice is who’s.)

I suppose I, too, was more annoyed than amused by Gold’s little joke at jazz’s expense and the reasons are pretty much in line with those enumerated over the last few days. To wit:

1.) You mean The New Yorker no longer has the time or space to cover jazz on a regular basis and THIS is what they decide to contribute instead?

2.) Jazz is still fighting to hold on to its sliver of the music marketplace and here’s one of the leading publications in the country demeaning its greatest living improviser? How dare they! Would they do this to Tom Stoppard or Suzanne Farrell or anybody in opera?

3.) It’s not all that funny to begin with. Why waste the space, especially at jazz’s expense? I’m probably leaving out a few other complaints, but these three are among the more frequent, making it easier to take them each of them one at a time:

1.) That the New Yorker hasn’t bothered finding room for regular jazz coverage, especially after establishing a tradition for such through the late Whitney Balliett is, of course, an ongoing scandal. But no one else in the magazine world is bothering with it either. I can understand concerns among my fellow jazz lovers that the snide tone informing this parody will convince the music’s haters of their fine judgment and good taste. I don’t know. Outright jazz hate is annoying, but widespread indifference is worse. Does anyone besides me remember Stanley Crouch’s 2005 straight-ahead New Yorker profile of Rollins? Do I remember any profile of any jazz musician since then of similar heft and dimension? I do not. And whenever a newspaper or mainstream publication paid me to write about jazz, I often felt as if I were dropping pebbles down a deep, dark well waiting for the splash. I’d like to think the furor aroused by Gold’s prank would shame editors into changing this situation. I know better. They’d prefer more pranks. So does the Internet. So do the people who get caught up in the Internet. I play the sincerity card with jazz because I respect it too much to do otherwise. But when I praise Sonny Rollins, I’m basically telling people what they already know, whether they’ve heard him for themselves or not. Snide plays better than sincere. Or don’t you listen to “Wait, Wait, Don’t Tell Me” every week on NPR? Figured as much.

2.) Nevertheless, I, too, would rather read or write about the latest installment of Rollins’ “Road Shows” albums than see somebody reduce Sonny to the rough equivalent of a petulant preppie. I’ve often said that while critics sometimes pump up everything Rollins does with little discrimination, the public-at-large seriously underrates or altogether ignores his glorious inventiveness. (Those who wonder why everybody in jazz got so riled by Gold’s piece should immediately buy Road Shows, Vol. 3 or, to get it all over with, Saxophone Colossus.) On the other hand, Gold or his editors must already think that Rollins has the kind of heft and dimension as a figure to be poked at and hazed in the public square, which is kinda sorta a backhanded acknowledgment of his significance. Would somebody do the same to Tom Stoppard or Suzanne Farrell or anybody in opera? You bet your sweet ass somebody would, anybody would, early and often! To say that jazz can’t take even the most half-baked pies tossed at its kisser is to make it seem as reductive as snobs in the higher elevations of Culture Gulch believe it to be.

3.) Then, too, opera buffs and balletomanes in those higher elevations are often regarded as humorless wet blankets who can’t abide the cheap jokes as their expense. The jazz cognoscenti may even acknowledge the irony that its collective cri-de-coeur over Gold’s blog only confirms the outer world’s suspicions that we’re all a bunch of insular, thin-skinned spoilsports who can’t take a joke. But that the joke in question needed a disclaimer to chill out the complainers may prove that the joke in question wasn’t all that funny to begin with. For what it’s worth, it’s a helluva lot funnier than Queenan’s smug tirade, though, unlike Queenan, Gold doesn’t seem at all sure of what he’s skewering in the first place — and neither does the reader. It’s a piece interested more in striking a pose than making a point. It assumes an attitude about something that isn’t the least bit connected or concerned with what its satirizing; unlike Donald Barthelme’s New Yorker story, “The King of Jazz,” which was the kind of blithe-but-pointed mockery that only a true fan (which Barthelme was) could pull off. Nevertheless, given the new-school dynamics of media transactions, strike a pose conspicuously enough and most of the gawkers will believe you’ve made your point anyway. And while jazz fans are shamed by Gold, he’s not shamed at all. He’s hearing tinkling sounds – bells, coins — whenever somebody mentions his name. If taking Gold to task for demeaning jazz makes me look like a slow-burning Edgar Kennedy to his blithe Harpo Marx, I’d just as soon go back to bed and wait for the wind to die down.

All this said, I’m glad, and even proud, that jazz got on its hind legs and roared back at this squib. The furor wont raise the music’s profile any higher than it is now. Too many other things have to happen for that to change. But as with that Spy magazine assault long ago, the effects of which I think I’m finally over by now, jazz under whatever name in whatever state will go on, oblivious to whatever the lovers and haters say about it. As I said earlier: I been here before. So will the divine mysteries of music. And so, I trust, will writers who can riff, lick and even vogue better than…no, sorry. I’m not going to mention the name again. I’d rather give my remaining time to this guy –– and, just as I eventually did twenty years ago, move on.

December 19th, 2011 — jazz reviews

Before we get to this year’s Top Ten, some random thoughts: 2011 has been such a mean, tumultuous, uprooting year for me that it was a challenge to keep track of the latest recordings. With the year almost over, I’m factory-sealed certain that I’ve left several worthy candidates behind. See them? They’re glaring at me from behind, standing with hands on hips or waving at my dust trail as if to say, “What?”

Then again, I find myself wondering what the hell they’re doing there. Seems to me I heard at some point this fall that Termination Day for CDs is approaching even faster than one had been led to believe. If we want the latest Keith Jarrett or Aaron Neville, we need only reach into a cloud — a.k.a. THE Cloud — and snatch whatever track we want. I still can’t believe that’s all we’ll eventually be left with. But it’s what all the salespeople insist is happening and they’ve never lied to us before. Ever.

And yet, you’re all here, aren’t you? Even though I haven’t yet learned how to download album covers or to make the necessary links to specific tracks. Someday, maybe even next year, that’ll be in place. For now, some tough choices from a tough year…

1.) Sonny Rollins, “Road Shows Vol. 2” (Doxy) – The Greatest Live Act in Jazz, headlined by the Greatest Living Improviser, keeps rolling along, its every flourish and delicacy captured for what promises to be an epochal series of recordings from past and (one hopes) future concerts. This second installment’s tracks are just a year old, but you understand why they needed to be out there in a hurry. They celebrate the start of the Colossus’ ninth decade as observed in Japan and, most notably, at last September’s “Sonny Rollins @80” concert @ New York’s Beacon Theater. On that evening, the celebrant, leonine and fit, sounded frisky and responsive to the electricity of the moment, his furry tone combed to a bristly sheen. He brought out guitarist Jim Hall, his comparably indefatigable 1960s playmate (to dive into “In a Sentimental Mood,” of course) as well as trumpeter Roy Hargrove who, as with the leader, always brings his A-game in front of onlookers. This disc is the next best thing to having been there. Yet it still makes you wish you’d been able to share the audience’s excitement at seeing Ornette Coleman wander on-stage for a characteristically insurgent solo on “Sonnymoon for Two” wherein he lures the Colossus “outside” the regular changes for some buoyant give-and-take. If Rollins is now the de-facto king of whatever it is we mean when we talk about jazz, then this edition of “Road Shows” shows him to be a wise, benevolent ruler whose domain, however small it may seem to outsiders, feels accessible enough to meet your most urgent needs and expansive enough to contain multitudes.

2.) Ambrose Akinmusir, “When the Heart Emerges Glistening” (Blue Note) – Only four years removed from winning the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Competition, this 29-year-old trumpeter has delivered on his grand promise with an album of startling depth and range. Once you get past the challenges of pronouncing his intimidating surname (ah-kin-MOO-sir-ee) and of getting past the album’s knotty title, you’re free to acclimate with his big, brilliant sound or unravel the intricacies of his soloing – which, while layered with the trills, glissandos and arpeggios emblematic of the jazz trumpet’s heritage, share the probing detail and varied attack of sax icon Joe Henderson and of pianist (and album co-producer) Jason Moran. For all his agility and command, Akinmusire leans heavily on his band-mates (tenor saxophonist Walter Smith III, pianist Gerald Clayton, bassist Harish Raghavan and drummer Justin Brown); all of whom are worthy collaborators, collectively and individually. Word is out that these guys are all part of a big band that Akinmusire is leading. Can’t wait to hear what that’s like.

2.) Ambrose Akinmusir, “When the Heart Emerges Glistening” (Blue Note) – Only four years removed from winning the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Competition, this 29-year-old trumpeter has delivered on his grand promise with an album of startling depth and range. Once you get past the challenges of pronouncing his intimidating surname (ah-kin-MOO-sir-ee) and of getting past the album’s knotty title, you’re free to acclimate with his big, brilliant sound or unravel the intricacies of his soloing – which, while layered with the trills, glissandos and arpeggios emblematic of the jazz trumpet’s heritage, share the probing detail and varied attack of sax icon Joe Henderson and of pianist (and album co-producer) Jason Moran. For all his agility and command, Akinmusire leans heavily on his band-mates (tenor saxophonist Walter Smith III, pianist Gerald Clayton, bassist Harish Raghavan and drummer Justin Brown); all of whom are worthy collaborators, collectively and individually. Word is out that these guys are all part of a big band that Akinmusire is leading. Can’t wait to hear what that’s like.

3.) Noah Preminger, “Before the Rain” (Palmetto) – At age 24, Preminger, a front-rank tenor saxophonist on just his second album as a leader, plays ballads as if he were a seventy-something road-warrior. He already knows, on instinct, how to approach a melody from behind; where to hang the drapery on a chord change and when to gently pull it away. And he doesn’t seem in a hurry to disclose everything he knows, not even on his original compositions (the title track, “Abreaction,” “Jamie”) or on Ornette Coleman’s “Toy Dance.” As with Akinmusire, Preminger is blessed with a eerily compatible rhythm section of bassist John Herbert, drummer Matt Wilson and pianist Frank Kimbrough, who contributes a couple of his prodigious compositions (“Quickening,” “November”) to the cause. By the time this group gets to massage a sturdy war horse such as “Until the Real Thing Comes Along,” you’re utterly convinced that Preminger is the real thing – and that he’s coming along quite nicely.

3.) Noah Preminger, “Before the Rain” (Palmetto) – At age 24, Preminger, a front-rank tenor saxophonist on just his second album as a leader, plays ballads as if he were a seventy-something road-warrior. He already knows, on instinct, how to approach a melody from behind; where to hang the drapery on a chord change and when to gently pull it away. And he doesn’t seem in a hurry to disclose everything he knows, not even on his original compositions (the title track, “Abreaction,” “Jamie”) or on Ornette Coleman’s “Toy Dance.” As with Akinmusire, Preminger is blessed with a eerily compatible rhythm section of bassist John Herbert, drummer Matt Wilson and pianist Frank Kimbrough, who contributes a couple of his prodigious compositions (“Quickening,” “November”) to the cause. By the time this group gets to massage a sturdy war horse such as “Until the Real Thing Comes Along,” you’re utterly convinced that Preminger is the real thing – and that he’s coming along quite nicely.

4.) Allen Lowe, “Blues and the Empirical Truth” (Music & Arts) – Is it music or is it scholarship? Or musical scholarship? Is it criticism of the blues or just critical of them (or at least of what people say about them)? These and dozens of other questions aroused by “Blues and the Empirical Truth” are far more significant than any answers I or anyone else pretending to know more about music than Allen Lowe can cobble together. Lowe is a gnomic, compulsively idiosyncratic polymath who lives in Maine, plays a red-hot saxophone and has for years put together epic inquiries into the history and nature of American music and how it shapes – or doesn’t – the national character. On this three-disc set, recorded over a two-year period, Lowe arranges, composes and plays “inside” and “outside” jazz as well as such makeshift forms as neo-gutbucket-progressive-punk (at least that’s what I’m calling it for the moment.) He is backed by a typically eclectic guest list that includes guitarist Marc Ribot, pianist Matthew Shipp, trombonist Roswell Rudd and Lowe’s fellow musicologist Lewis Porter, contributing here and there on keyboards. Along the way, tribute is made to civil rights activists Pauli Murray and Ella Mae Wiggins, forgotten or obscure musicians such as saxophonist Dave Schildkraft and pianist Blind Tom Bethune and…Doris Day, who should have been invited to Portland to jam with this crowd; except you have to wonder what she would have made of a song list with such titles as “Speckled Shaw Crippled Pete Boogie,” “Blues in Transfiguration,” “Elvis Died With His Sins Intact,” “In a Harlem Ashram” and “(Bull Connor Sees) Darkies on the Delta.” Guess it doesn’t matter as long as no animals were harmed in the process.

4.) Allen Lowe, “Blues and the Empirical Truth” (Music & Arts) – Is it music or is it scholarship? Or musical scholarship? Is it criticism of the blues or just critical of them (or at least of what people say about them)? These and dozens of other questions aroused by “Blues and the Empirical Truth” are far more significant than any answers I or anyone else pretending to know more about music than Allen Lowe can cobble together. Lowe is a gnomic, compulsively idiosyncratic polymath who lives in Maine, plays a red-hot saxophone and has for years put together epic inquiries into the history and nature of American music and how it shapes – or doesn’t – the national character. On this three-disc set, recorded over a two-year period, Lowe arranges, composes and plays “inside” and “outside” jazz as well as such makeshift forms as neo-gutbucket-progressive-punk (at least that’s what I’m calling it for the moment.) He is backed by a typically eclectic guest list that includes guitarist Marc Ribot, pianist Matthew Shipp, trombonist Roswell Rudd and Lowe’s fellow musicologist Lewis Porter, contributing here and there on keyboards. Along the way, tribute is made to civil rights activists Pauli Murray and Ella Mae Wiggins, forgotten or obscure musicians such as saxophonist Dave Schildkraft and pianist Blind Tom Bethune and…Doris Day, who should have been invited to Portland to jam with this crowd; except you have to wonder what she would have made of a song list with such titles as “Speckled Shaw Crippled Pete Boogie,” “Blues in Transfiguration,” “Elvis Died With His Sins Intact,” “In a Harlem Ashram” and “(Bull Connor Sees) Darkies on the Delta.” Guess it doesn’t matter as long as no animals were harmed in the process.

5.) Muhal Richard Abrams, “SoundDance” (Pi) – Just so you know, Sonny Rollins isn’t the only octogenarian legend who’s still getting the job done. Abrams, the peerless pianist-composer who co-founded the legendary Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) nearly 50 years ago, marked his own ninth decade by engaging in colloquies of such breadth and magnitude that they each needed their own disc. One of these is a dialogue with tenor saxophonist Fred Anderson that took place in October, 2009, a year before the latter’s death, though it’s a strain to detect signs of sagging energy in his playing. Both Abrams and Anderson seem energized by the task of extending or enhancing each other’s thoughts and even listeners resistant to free-form improvisation won’t miss a beat (so to speak). A year later, Abrams engaged in a sonic pas de deux with fellow innovator, author and AACM veteran George Lewis, who brought both his trombone and his laptop to the party. These two masters of orchestration create intricate, spiraling patterns that are at once imposing and puckish. You can wander in and out of their gallery of sound and find something strange, shiny and, in a peculiar way, companionable.

5.) Muhal Richard Abrams, “SoundDance” (Pi) – Just so you know, Sonny Rollins isn’t the only octogenarian legend who’s still getting the job done. Abrams, the peerless pianist-composer who co-founded the legendary Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) nearly 50 years ago, marked his own ninth decade by engaging in colloquies of such breadth and magnitude that they each needed their own disc. One of these is a dialogue with tenor saxophonist Fred Anderson that took place in October, 2009, a year before the latter’s death, though it’s a strain to detect signs of sagging energy in his playing. Both Abrams and Anderson seem energized by the task of extending or enhancing each other’s thoughts and even listeners resistant to free-form improvisation won’t miss a beat (so to speak). A year later, Abrams engaged in a sonic pas de deux with fellow innovator, author and AACM veteran George Lewis, who brought both his trombone and his laptop to the party. These two masters of orchestration create intricate, spiraling patterns that are at once imposing and puckish. You can wander in and out of their gallery of sound and find something strange, shiny and, in a peculiar way, companionable.

6.) Craig Taborn, “Avenging Angel” (EMI) – A title of one track could easily apply to most of the others: “A Difficult Thing Said Simply.” Taborn, who owns one of the most eclectic curriculum vitae in contemporary music (Tim Berne AND James Carter?), approaches the art of solo jazz piano as if he were translating complex code from a distant star. Often, he binds the information in tightly-wound chords struck down as if on anvils to forge unusual shapes. At other times (the aptly-named “Glossolalia”), he lets things twirl in the air like dazed, tiny phantasms squeezed out of an overcrowded basement. As with the early work of Keith Jarrett, Taborn is prone to lean to too hard on a riff, but (again, as with Jarrett) the digging can occasionally lead to an illuminated strike. In what’s been a vintage year for solo jazz piano discs (see the honorable-mention list below), this stood out for one simple reason: It sounded the most different from what its genre had yielded before.

6.) Craig Taborn, “Avenging Angel” (EMI) – A title of one track could easily apply to most of the others: “A Difficult Thing Said Simply.” Taborn, who owns one of the most eclectic curriculum vitae in contemporary music (Tim Berne AND James Carter?), approaches the art of solo jazz piano as if he were translating complex code from a distant star. Often, he binds the information in tightly-wound chords struck down as if on anvils to forge unusual shapes. At other times (the aptly-named “Glossolalia”), he lets things twirl in the air like dazed, tiny phantasms squeezed out of an overcrowded basement. As with the early work of Keith Jarrett, Taborn is prone to lean to too hard on a riff, but (again, as with Jarrett) the digging can occasionally lead to an illuminated strike. In what’s been a vintage year for solo jazz piano discs (see the honorable-mention list below), this stood out for one simple reason: It sounded the most different from what its genre had yielded before.

7.) Youn Sun Nah, “Same Girl” (ACT) – Didn’t know a thing about her when this disc slipped into in my mailbox earlier in the year. After one track, I found myself asking, “Where has she been all my life?” (In Europe, apparently, where this album was first released last winter.) She is steeped in the French chanson tradition, but as with the most interesting singers beyond the boomer generation – Is she really 42? – she’s willing to try anything from Broadway (“My Favorite Things”) to Brazil (“Song of No Regrets”), from the folk music of her native Korea (“Kangwondo Aririang”) to the mellow sounds of Metallica (“Enter Sandman”). And she can scat real good, too, as proven on the quiet-fire “Breakfast in Baghdad.” The minimalist backing she gets from guitarist Ulf Wakenius, bassist-cellist Lars Danielson and percussionist Xavier Desandre lets her rangy, limber voice roam, run and leap about at will, even when the material is dipped in deep blue. Nothing seems to scare or stop her. Good as this disc is, it makes you wish she’d dare even more.

7.) Youn Sun Nah, “Same Girl” (ACT) – Didn’t know a thing about her when this disc slipped into in my mailbox earlier in the year. After one track, I found myself asking, “Where has she been all my life?” (In Europe, apparently, where this album was first released last winter.) She is steeped in the French chanson tradition, but as with the most interesting singers beyond the boomer generation – Is she really 42? – she’s willing to try anything from Broadway (“My Favorite Things”) to Brazil (“Song of No Regrets”), from the folk music of her native Korea (“Kangwondo Aririang”) to the mellow sounds of Metallica (“Enter Sandman”). And she can scat real good, too, as proven on the quiet-fire “Breakfast in Baghdad.” The minimalist backing she gets from guitarist Ulf Wakenius, bassist-cellist Lars Danielson and percussionist Xavier Desandre lets her rangy, limber voice roam, run and leap about at will, even when the material is dipped in deep blue. Nothing seems to scare or stop her. Good as this disc is, it makes you wish she’d dare even more.

8.) Bill Frisell, “Sign of Life” (Savoy) – At its most inquisitive and unfettered, Bill Frisell’s music can be as evocative of the “the old, weird America” as Bob Dylan’s 1967 basement tapes. (Come and get me, Greil Marcus!) He has a boho-folk artist’s affinity for both the pastoral and the abstract. Beneath even his most glowing, spacious-skies landscapes, there are flickering shadows and misshapen objects that don’t distort the view, but are blended to make a slightly cockeyed, but still arresting picture, “Sign of Life,” performed by his 858 Quartet of violinist Jenny Schienman, violist Eyvind Kang and cellist Hank Roberts, is his best-realized sound painting since 2001’s “Blues Dream,” whose noir-ish cloaking devices I still appreciate, even if others didn’t. This is a sunnier compound of motifs and riffs that give off an aura of mystery, even danger – especially when the irrepressible Scheinman starts throwing paraphrases and adornments like left jabs. It’s clearer than ever that with both this disc and the John Lennon tribute released in the same year, Frisell can’t be stopped – or even contained. Only sampled – and what would NPR do for filler between news stories if his music weren’t around?

8.) Bill Frisell, “Sign of Life” (Savoy) – At its most inquisitive and unfettered, Bill Frisell’s music can be as evocative of the “the old, weird America” as Bob Dylan’s 1967 basement tapes. (Come and get me, Greil Marcus!) He has a boho-folk artist’s affinity for both the pastoral and the abstract. Beneath even his most glowing, spacious-skies landscapes, there are flickering shadows and misshapen objects that don’t distort the view, but are blended to make a slightly cockeyed, but still arresting picture, “Sign of Life,” performed by his 858 Quartet of violinist Jenny Schienman, violist Eyvind Kang and cellist Hank Roberts, is his best-realized sound painting since 2001’s “Blues Dream,” whose noir-ish cloaking devices I still appreciate, even if others didn’t. This is a sunnier compound of motifs and riffs that give off an aura of mystery, even danger – especially when the irrepressible Scheinman starts throwing paraphrases and adornments like left jabs. It’s clearer than ever that with both this disc and the John Lennon tribute released in the same year, Frisell can’t be stopped – or even contained. Only sampled – and what would NPR do for filler between news stories if his music weren’t around?

9.) Miguel Zenon, “Alma Adento: The Puerto Rican Songbook” (Marsalis Music) – Not only was this the year’s best Latin jazz album, it was also among the more inspired examples of that overpopulated subgenre, the tribute album. Zenon’s homage isn’t to a single artist or composer, but to the men and women who wrote the classic pop tunes of his native land. He and arranger Guillermo Klein practically reinvent crooner Bobby Capo’s “Incomprendido” as a slow-drying lament. Conversely, Rafael Hernandez’s “Silencio,” revived by the “Buena Vista Social Club” some years back, is given a near-chimerical, tempo-shifting transformation. The centerpiece, literally and figuratively, comprises two pieces by Sylvia Rexach: the title track and “Olas y Areenas,” both of which are treated by Zenon and Klein with passionate intensity and solicitous intelligence. Zenon may sometimes risk going overboard with his ambition and with his playing, but that’s part of the attraction. And if his alto-sax soars like a rocket plane, he’s becoming more adroit at gliding to pinpoint landings. .

9.) Miguel Zenon, “Alma Adento: The Puerto Rican Songbook” (Marsalis Music) – Not only was this the year’s best Latin jazz album, it was also among the more inspired examples of that overpopulated subgenre, the tribute album. Zenon’s homage isn’t to a single artist or composer, but to the men and women who wrote the classic pop tunes of his native land. He and arranger Guillermo Klein practically reinvent crooner Bobby Capo’s “Incomprendido” as a slow-drying lament. Conversely, Rafael Hernandez’s “Silencio,” revived by the “Buena Vista Social Club” some years back, is given a near-chimerical, tempo-shifting transformation. The centerpiece, literally and figuratively, comprises two pieces by Sylvia Rexach: the title track and “Olas y Areenas,” both of which are treated by Zenon and Klein with passionate intensity and solicitous intelligence. Zenon may sometimes risk going overboard with his ambition and with his playing, but that’s part of the attraction. And if his alto-sax soars like a rocket plane, he’s becoming more adroit at gliding to pinpoint landings. .

10.) Evan Christopher, “Remembering Song” (Arbors) – If you paid close attention to “Treme” this year…no, wait. I have to digress just a little here. I’ve been hearing fans of “The Wire” complain that they find “Treme” too slow, too dense and not as – what? – urgently engrossing as its predecessor. I am compelled to remind these folks that it took at least three seasons for “The Wire” to find a following. And that only when it was nearly over did people begin thinking of it as a “classic.” So though it’s no longer fashionable in pop-culture circles to counsel patience, call me unfashionable. Watch and wait…Anyway, if you did pay close attention to “Treme,” you probably saw Christopher jamming with Tom McDermott and the luminous Lucia Micarelli on Scott Joplin’s “Heliotrope Bouquet.” He has been one of Crescent City’s most lyrical and stalwart clarinetists and this love letter to his adopted hometown is both a wistful lament for the unshakable legacy of Katrina and a bittersweet celebration of the spirit that refuses to wither or retreat from that legacy. His original compositions – e.g., “The River by the Road”, “You Gotta Treat It Gentle” – show that he’s not trying to reinvent tradition, but fulfill its demands. Sometimes, you don’t need to listen to something that changes the world. Easing its pain is enough. And for me, this year especially, it was more than enough.

10.) Evan Christopher, “Remembering Song” (Arbors) – If you paid close attention to “Treme” this year…no, wait. I have to digress just a little here. I’ve been hearing fans of “The Wire” complain that they find “Treme” too slow, too dense and not as – what? – urgently engrossing as its predecessor. I am compelled to remind these folks that it took at least three seasons for “The Wire” to find a following. And that only when it was nearly over did people begin thinking of it as a “classic.” So though it’s no longer fashionable in pop-culture circles to counsel patience, call me unfashionable. Watch and wait…Anyway, if you did pay close attention to “Treme,” you probably saw Christopher jamming with Tom McDermott and the luminous Lucia Micarelli on Scott Joplin’s “Heliotrope Bouquet.” He has been one of Crescent City’s most lyrical and stalwart clarinetists and this love letter to his adopted hometown is both a wistful lament for the unshakable legacy of Katrina and a bittersweet celebration of the spirit that refuses to wither or retreat from that legacy. His original compositions – e.g., “The River by the Road”, “You Gotta Treat It Gentle” – show that he’s not trying to reinvent tradition, but fulfill its demands. Sometimes, you don’t need to listen to something that changes the world. Easing its pain is enough. And for me, this year especially, it was more than enough.

HONORABLE MENTION:

1.) Gonzalo Rubalcaba, “Fe Faith” (5Passion)

2.) Matthew Shipp Trip, “The Art of the Improviser” (Thirsty Ear)

3.) Larry Goldings, “In My Room” (BFM)

4.) Charles Lloyd & Maria Farantouri, “Athens Concert” (EMI)

5.) Terrell Stafford, “This Side of Strayhorn (MaxJazz)

BEST NEW ARTIST

Chris Dingman, “Waking Dreams” (Between Worlds Music)

BEST VOCAL

Youn Sun Nah, “Same Girl” (see above)

BEST LATIN ALBUIM

Zenon, “Alma Adento: The Puerto Rican Songbook” (see above)

BEST REISSUE

Julius Hemphill, “Dogon A.D.” (Arista/Freedom) HONORABLE MENTION: Bill Dixon Orchestra, “Intents and Purposes” (RCA/Dynagroove)