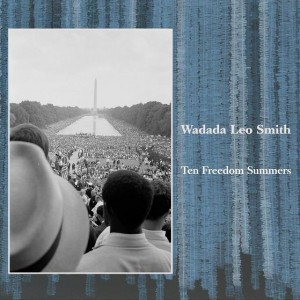

The best jazz recording of 2012, much like science or magic, doesn’t easily yield its secrets – which is the main reason it didn’t make my Top-10 list. I simply didn’t get to it all in time. Still, with or without me (and gratifyingly so), Wadada Leo Smith’s Ten Freedom Summers has by now received most of the formal acclamation it deserves: Finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in music, awards from the Jazz Journalists Association for Smith as musician and trumpeter of the year, a three-night live premiere last week at the Roulette in Brooklyn. I suspect that once the four-disc set on Cuneiform Records seeps into the shared consciousness of receptive listeners, it will continue to provoke, haunt and inspire. The greatest music – the greatest anything – doesn’t end when you stop absorbing it. Your reactions, primary and secondary, are part of the artistic process. They’re supposed to be, anyway.

Each of the nineteen compositions in Smith’s five-plus-hour opus announces itself as a chapter in American history from the 1857 Dred Scott case to the 9/11 terrorist attacks. But the thematic core of Ten Freedom Summers, as its title suggests, is the decade of national transformation that began with the 1954 Supreme Court decision declaring school segregation unconstitutional and the 1964 summer that saw both Congress’s passage of the most sweeping civil-rights legislation since Reconstruction and the Mississippi “Freedom Summer” Project during which activists risked (and lost) their lives trying to enfranchise the state’s besieged African-Americans. With Smith on trumpet leading both his Golden Quartet/Quintet of pianist Anthony Davis, bassist John Lindberg, percussionists Pheeroan ak-Laff and Susie Ibarra and the nine-member Southwest Chamber Music Ensemble conducted by Jeff von der Schmidt, the work spools forth as a meticulous inventory of mood more than a sweeping pageant of struggle. It doesn’t chronicle its noteworthy events so much as search for their deeper emotional currents and, in doing so, compels the listener to react to history beyond text and shadow – and even further beyond the blithely-dispensed shorthand of newsreels, archival photos and sound bites.

I wonder, though, whether I’m probing or merely projecting whenever I hear some of its chapters. Just to take one example, the piece entitled, “Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott, 381 Days.” It begins with a major-key dirge by Smith’s trumpet, with a tone and tempo reminiscent of such mid-1960s elegiac milestones as Lee Morgan’s “Search for the New Land” and John Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme.” One can easily interpret this table-setting incantation as signaling the no-turning-back-now gesture by Parks in her epoch-making refusal to sit in the back of an Alabama public transport. Then, for several bars afterward, a chugging 4/4 beat, driven by ak-Laff with bouncy strides, conveys the “381 Days” of the resultant boycott, which forced hundreds of domestics, office workers and laborers to walk instead of ride to work and shop, thus representing the first of the era’s significant civil-rights marches.

I’m confident I’ve sussed that out correctly. But when I hear the strains of bluesy strutting at either end of “Thurgood Marshall and Brown Vs. Board of Education: A Dream of Equal Education,” am I being cued to imagine the swagger and bravado of its eponymous heroic lawyer making his way through several litigious hurdles to reach his finish line at the Highest Court in the Land? And would I know enough to respond to such cues if I didn’t know what its title was? Or, for that matter, know who Thurgood Marshall was and the kind of ribald, larger-than-life figure he was?

It helps to know the history behind the music. But it’s not necessary. Because even if you can sense why Smith and his musicians make the choices in what they play and how they extend their ideas (together or separately), it’s the spacious-skies expansiveness of the concept itself, its willingness to do the unexpected – a segment on the “Black Church” that’s all swirling chamber music and no gospel tropes whatsoever – and let you deal with its implications, that allow you to sense that “freedom” is far more than the theme of Smith’s work here. It’s both his method and his objective.

Smith, after all, was forged in the crucible of what, for want of a better description, we still label “avant-garde jazz.” And what would be a better description? There are so many options. Some like “progressive jazz,” though you kind of feel an anachronistic draft when you hear those words. Others cling to such sixties taglines as “New Thing,” “Fourth Stream,” “Outside” and even “Free Jazz,” though some of the renegades of subsequent decades embraced old-school polyphony that kept things flying in fairly close order. Gary Giddins quixotically tried to coin the word, “parajazz” (or was it “Para-Jazz”?) as an all-purpose umbrella. I like it, but I can’t find anybody else who does.

I also like “creative music” — bringing us back to Smith, who was part of the groundbreaking Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) that nurtured and/or inspired such experimentalists as Henry Threadgill, Anthony Braxton, Roscoe Mitchell, Joseph Jarman, George Lewis, Leroy Jenkins and many more. Their music was as idiosyncratic, original and unconventional as they were. Jazz fans who drew their lines at whatever Miles Davis was doing in 1965 (if not sooner) thought the AACM and their kind were too “way out” to even taste. But back in the seventies, I warmed to the freewheeling, sometimes breakneck invention of the renegades. It’s true they made mosaics out of traditional rhythmic pattern and carried thematic ideas down dark alleys and wooded glades you never thought of visiting. But as with avant-gardists of the past, they weren’t upending the order-out-of-chaos imperative of art as much as encouraging listeners to re-fashion or, at least, reconsider their own notions of order. In other words, they weren’t the only ones creating the music; you had to join in the process, too. And where previous generations did so by dancing, we did it by thinking or feeling our way through the changes.

Smith, now 71, has for decades advanced his own vision of creativity into finding new ways of fusing improvisation and notation. (He explains this process in far greater detail here, though, as with his music, one run-through won’t be enough.) Ten Freedom Summers uses the late 20th century’s upheaval to apply firmer context to the process. Those unaccustomed to such compulsively creative composition may think it’s haphazard, even if they know the historical facts being represented or dramatized. But as it was with the avant-garde’s loft concerts of the 1970s or for that matter, some of the late, lamented Knitting Factory’s wilder nights of the 1990s, the whole idea was to listen and to be attentive always for whatever is familiar in one’s own memory, private or public, and for what could be something you never knew before. From such surprises, you can make your own connections to this freedom struggle – or any other such struggle you can imagine. It may well have been this openness to possibility that the Pulitzer committee recognized in almost-but-not-quite giving their top prize to Ten Freedom Summers. If so, then it’s a whole way of thinking about music, and not just jazz, that’s received its just desserts.