It’s Sunday afternoon in the Universe and one of the appliances in my apartment insists on telling me that football is back. I change the channel to make it stop, but there are at least several other voices on other channels screaming the same thing. I flip over to Turner Classic Movies, which is showing Alfred Hitchcock’s Suspicion, and I could swear Cary Grant is telling Joan Fontaine that football is back. (Probably trying to make her crazy or paranoid or something…)

Once upon a time and not all that long ago, I would have been tingly and warm all over with the idea of football being back in my life. But I’m not feeling it so much now. Given what’s been happening with professional football over the last few years, I can’t imagine any sentient being with any degree of empathy embracing block-and-tackle football with unconditional love and abandon. Fear and loathing may be closer, but still too extreme in the other direction.

Speaking of fear and loathing: Hunter S. Thompson once characterized pro football as “a hip and private kind of vice to be into.” He was, at the time — 1974 – applying those words in the past tense since by that time, then-commissioner Pete Rozelle had already been referring to professional football as “The Product.” Thompson yearned for his version of the good old days of watching the 49ers play at decrepit Kezar Stadium in the mid-1960s “with 15 beers in a plastic cooler and a Dr. Grabow pipe filled with bad hash” while trying to avoid the mean drunks looking for reasons to punch somebody out, especially if the Niners were losing, as happened frequently in those days.

But even in those funkier times, pro football had already become a “Product” with competing brand names (a.k.a. NFL vs. AFL) willing themselves toward merger through the irresistible might of television revenues. The outlaw mystique that Thompson pined for was by 1965 already being nudged aside for what would, by the country’s Bicentennial 11 years hence, become a family-friendly franchise of hype and muscle itching to spread its influence beyond the USA’s boundaries.

The astonishing rise of the National Football League from sandlot outlier to global money machine remains the prevailing narrative of American-style football, a bedtime story the management class loves to hear before drifting back to sleep. You can tell, though, that even the NFL begins this season more nervous and self-conscious about its own standing.

What’s been called “the health crisis” is the biggest factor and the cumulative effect of concussions on pro players’ lifespans isn’t the half of it. (The league’s ham-handed attempts to degrade, if not outright lie about the evidence are even worse.) But what that scandal has done most tellingly is widen the space for scrutinizing other discomfiting aspects of America’s Game that are killing or, at least, muting the buzz of unconditional fandom.

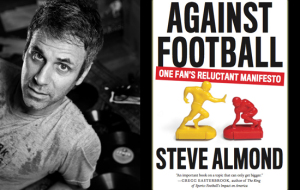

Against Football (Melville House) is written by Steve Almond, who describes himself as a long-time and, more recently, long-suffering Raiders fan. It’s probably a given that he writes this silken-swift j’accuse more from sorrow than anger; though he still sounds pretty mad at the NFL and, in equal measure, with “the two disparate synapses that fire in my brain that when I hear the word, “football”: the one that calls out, Who’s playing? What channel? and the one that murmurs, Shame on you.” This is from his introduction. He has me at “Hello.”

Almond goes on to debunk, among other things, the fallacy of the league’s “socialism” based on its revenue-sharing policy, which, through “a canny form of market manipulation” along with deft congressional lobbying allowed the NFL to circumvent anti-trust regulations. He also stretches open, to wince-inducing degrees, the homophobia, sexism and racism, conscious or otherwise, that fester beneath the sleek, supposedly more humane surface of 21st century play-for-pay tackle football. One chapter is entitled, “The Love Song of Richie Incognito,” which, given the story behind that name, sounds like a movie worth making, if not seeing. Another chapter title, “Their Sons Grow Suicidally Beautiful,” is taken from a James Wright poem about football (the best such poem from an American) and takes up the myriad ills of “amateur” football at all levels; not least of which the manner in which the collegiate game has become little more than a feeder system for the pro league in both manpower and added publicity, which, at this point, it can never get enough of. (I’m kidding.)

These and many other defects tabulated in Against Football aren’t exactly news to those old enough to have read the first-hand accounts of such renegade players of the sixties as Dave Meggysey, Bernie Parish and Peter Gent. But because Almond’s book is aimed as much as his own psyche as it is at ours, the passages that sting the most delve into the psychology of football fandom. He quotes, from Frederick Exley’s A Fan’s Notes, how the book’s autobiographical surrogate “gained…the feeling of being alive” from watching Giants games in dive bars. “His hero,” Almond writes of Exley, “looks to the Giants each Sunday to awaken him from the spiritual stupor of his life. That could be religion – or addiction.” (Italics added.)

I envision millions of people who hate the game but love a fan in their lives nodding their heads in rueful recognition of this phenomenon. And yet neither Almond nor I have easy answers as to whether being ambivalent about the game, but watching it anyway is a more destructive equivalent to substance abuse than loving the game while completely ignoring its moral and ethical lapses. That the question is posed at all raises this book above the level of a mere screed.

As trenchant as Almond is, he remains solicitous and compassionate throughout towards those whose devotion to football remains absolute. At one point, he quotes a close friend who, upon hearing of the book Almond intends to write, implores, “Please don’t take this away from me.” Towards the end, he’s utterly abased by a conversation he has with a young woman, a lifelong Philadelphia Eagles fan who tells him that football “was what kept her connected to her hometown, and to her dad especially.” Guess how low he felt when he answered her query as to what his book was about.

The Eagles. They do seem to inspire a river-deep-mountain-high devotion in their fan base. I spent eight years living and working in Philadelphia and though I was never converted to the Eagles cause (I do think you need to have grown up there to truly belong), I appreciated the city’s collective investment of passion somewhat more than those who from a distance view Eagles fans with varying degrees of alarm. Having interviewed those fans in full fury (and illumination) against their team, I can say that while they can be…how to put this…vivid in their expressiveness, I felt very safe in their company – as long as I never told them that I’d grown up in a Giants household. Such intense devotion along with a substantial historic legacy in professional football deserves more than one measly championship in the last 55 years to show for it.

Ray Didinger grew up an Eagles fan and spent most of his professional life writing about them for at least two local newspapers. He walks the walk, talks the talk of the true fan, but he’s so much more composed and rational about his engagement, which makes the second edition of The New Eagles Encyclopedia (Temple University Press), revised by Didinger from the 2005 edition he’d composed with the late Robert S, Lyons, both an invaluable tonic for the stressed-out Eagles follower and an absorbing read for anyone who savors colorful history and folklore, no matter where it’s from or what it’s about.

To pluck one example from many: Didinger’s chapter, new for this edition, about the team’s rivalry with the Dallas Cowboys. OK, OK…like, almost everybody has a rivalry with the Dallas Cowboys; at times, the Cowboys even hate themselves. But with the Eagles, it’s as if there are festering internal injuries that haven’t healed with time. And Didinger, who’s got the memory of an intelligence agency’s deep-background file system, reaches back to the mid-1960s when the two teams traded a series of wins and losses that climaxed with a jaw-breaking, teeth-severing clothesline tackle on Philadelphia running back Timmy Brown by Dallas linebacker Lee Roy Jordan. Eagle partisans maintain to this day that Jordan’s hit was late and cheap. Jordan insists otherwise. What Didinger characterizes as a “blood feud” was established from then on.

Brown, for what it’s worth, retained sufficient enough use of his oral equipment to have to a respectable career as a screen actor. (He’s in Nashville! Singing!) But in the context of this species of football book, physical injury is just the spoke on a wheel whose hub is the process of professional athletics itself. And even at a time when thoughtful people are coming to grips with their long-term affection for a brutal sport, Didinger’s book reminds you that devotion to a team and the people who live and die with its every game isn’t the only thing to think about when thinking about football. But for many people, it’s everything…and, much as some of us may disagree, enough.