I’m going to say it was 1993 because who’s going to tell me it wasn’t, right? It was, in any case, one of those blessed years when a good chunk of my weekly salary was earned talking regularly to jazz musicians and I was having an especially jovial and illuminating conversation with McCoy Tyner about, mostly, the big band he sometimes, though not often enough, drove onto concert stages. Somewhere, the talk took a slight veer into the tricky issue of progenitors and I asked Tyner what he thought of Erroll Garner.

Why? This is where it gets hazy, because I’m not altogether sure how it came up unless Garner came to my packrat mind as an example of a jazz pianist who rarely (if ever) fronted or accompanied large ensembles, owing to a sprawling, multi-layered attack that telegraphed plenty of orchestration on its own. I also think that I was hearing much of the same lavish, often rousing ornamentation in Tyner’s late style – though I thought it prudent not to frame the question in this fashion.

Tatum, Monk, Bud Powell…these were the names Tyner was willing, even eager to claim as influences. But Erroll Garner? Not so much and, though I never used his remarks on this topic till now, I distinctly remember him saying of Garner, not unkindly, that unlike the others in his pantheon, “he never made the piano sound like anything other than a piano.”

I thought, back then, I knew what Tyner meant; that Garner, whatever his many attributes, wasn’t considered one of those innovators who transformed the landscape around them, and not just jazz, or the piano. As I say, I didn’t use the material in my piece, in large part because I thought Tyner’s estimation was a kinder, gentler variation of the ways in which Garner’s once-glowing reputation had dimmed along jazz’s upper reaches.

Not that plenty of people weren’t trying hard twenty-something years ago to stoke those fires again; esoteric classicists such as Dick Hyman would talk Garner up any chance he got. Always there were the inexhaustible efforts of Garner’s manager Martha Glaser, whose devotion to her client’s best interests endured well beyond her client’s death in 1977. She was always ready to talk on the phone about Garner and promote an event celebrating his legacy – and on those occasions when I obliged her, I routinely insisted to my readers that Erroll Garner deserved to remembered as much more than the man who wrote “Misty.”

My readers, I like to think, may have been smarter about such things than musicians since Garner’s crowd-pleasing, readily accessible swing left them feeling very happy. Glaser herself died a year ago next month at 93. What’s happened since would make her very happy.

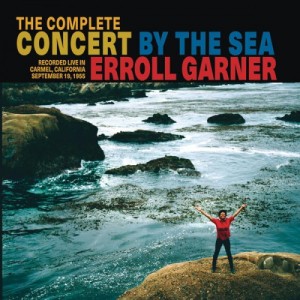

For this has been the year that Erroll Garner’s reputation has been rejuvenated by the release in September of The Complete Concert by the Sea (Sony Legacy), a three-disc package that presents in unedited form on the first two discs the live performance on September 19, 1955 (yes, if you’re scoring, 60 years ago) by Garner, drummer Denzil Best and bassist Eddie Calhoun in what is now the Sunset Arts Center in Carmel, California. The third disc offers the same edited version of the concert that, along with Time Out and Kind of Blue, became one of Columbia’s evergreen jazz LPs of the decade.

Not everybody loved it, though I never quite understood the beefs since they seemed to have little if anything to do with the music. After I finally bought my own copy of the original LP in the mid-1970s having heard so much about it for years, a perpetually grouchy friend of mine sneered that it wasn’t an album so much as a mood-setting accessory for “swinging” bachelors. This jaundiced view, I’m embarrassed to say, held unjust dominion over my own; when at first, I was captivated by Garner’s high spirits, jaunty humor, and infectious cleverness, I would instead see these qualities as happy hour ruffles and flourishes intended to get a rise out of the Carmel crowd, which seemed cued to applaud every ornate lick and at every point when a familiar melody made its presence known. Then and now, I wondered what they were really clapping for: Garner’s prefatory inventions or their own ability to, so to speak, Name That Tune when it materialized.

And yet, my inner crank was at war with my even younger self, who was enchanted with Garner’s witty, crafty 1947 solo, “Frankie and Johnny Fantasy” or immersed myself in my parents’ 1967 LP, That’s My Kick, with its double conga drums and hooky original compositions, “Nervous Waltz” and “Like It Is.” A self-taught, ambidextrous pianist who couldn’t help growling at the keyboard seemed eccentric enough to avoid being diminished as lightweight. Yet as with such sui generis pianists as Ahmad Jamal and Keith Jarrett (who also makes strange noises while he plays), Garner’s popularity with the public seemed something of an indictment to jazz snobs.

But as with the futile complaints against Ella Fitzgerald’s unfettered glee in invention, carping against Garner’s similar instincts for joy and fun is ultimately a losing battle. Also, Garner is held in high regard by such jazz-snob favorites as Martial Solal and Cecil Taylor, who (again, if memory serves) thought the free-form preludes Garner often indulged before he dug into a melody were too often overlooked on their own merits. The peerlessly resourceful contemporary pianist Geri Allen is one of the principal forces behind restoring The Complete Concert by the Sea to the marketplace and her contribution to the liner notes makes a persuasive case for “Mr. Garner’s innovative, singular piano technique and exuberant musicality personifies a joy of fearless virtuosity and exploration…the very spirit of swing, free improvisation and the blues.”

Suits me, and apparently it likewise suits the critical cognoscenti who have all but unanimously deemed this package the year’s best re-issue – though I suppose it’s not technically a reissue if it’s more than doubling the original LPs 11 tracks with previously unreleased pieces, including a near-breathtaking turn on “The Nearness of You” and a deeply satisfying run-through of “Bernie’s Tune.”

More than anything, the set has put Garner’s name back in play for pantheon status, though who really wants to engage in that game when Joy is the final arbiter? I’ll let that somewhat confounding question sit in mid-air while one begins reconsidering how much Erroll Garner lives in the spirits of jazz pianists past and present, young and old, “progressive” and “mainstream” (or however you make such distinctions in your own mind). Other than similar re-packaged goods it augurs, Complete Concert by the Sea opens up that potentially delicious discussion. And whatever its virtues of resiliency, “Misty” hasn’t all that much to do with it.