(On 115th anniversary of what, according to his Baptismal certificate, was Louis Armstrong’s actual birth date, I am reposting a piece I wrote in 2001 for SeeingBlack.com & for whatever reason, is now lost in the digital ether.)

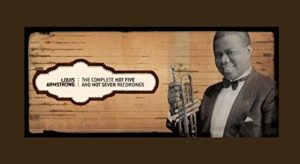

Louis Armstrong may be the only American musician who gets two centennial celebrations. He is certainly the only one who deserves them. Last year, nodding to the July 4, 1900 date Armstrong believed to be his birthday, record companies unloaded a rich harvest of retrospectives and boxed sets, notably Columbia-Legacy’s four-disc The Complete Hot Five and Hot Seven Recordings of Louis Armstrong, with the history-making sessions between 1925 and 1929 that, in essence, created 20th century music.

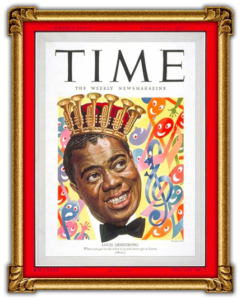

Given the relatively recent discovery that Armstrong was actually born August 4, 1901, the centennial celebrations are likely to continue through the end of this year. The keynote was certainly struck in January with the broadcast of Ken Burns’ epochal PBS series, Jazz. Armstrong’s spirit informs all 19 hours of the documentary, establishing him—once and for all and in timely fashion—as a towering figure in world history. People in other countries had no trouble with this notion. In Europe, he was an important musical artist. In Africa, he was a king. If you doubt this, watch documentary footage of Armstrong’s concert tour of that continent. They knew they were in the presence of a hero. Though you may find few who’ll admit it now, there were many black folks in this country who doubted this, including me.

I know now that I badly needed Louis Armstrong as a hero when I was growing up. Being a creative child who was never happier than when I was drawing pictures, making up skits or putting strange words or sounds together, I couldn’t possibly have found more positive reinforcement for my undefined dreams than the first great American improviser himself. Armstrong’s own account of his 16-year-old self, playing a horn in a rough Mississippi River-front honky-tonk, exemplified the kind of self-containment and artistic poise to which I’d subconsciously aspired ever since I learned to read and write:

“[The Brick House]…was one of the toughest joints I ever played in…Guys would drink and fight one another like circle saws. Bottles would come flying over the bandstand like crazy and there was lots of plain common shooting and cutting. But somehow all that jive didn’t faze me at all. I was so happy to have some place to blow my horn.” (From Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans, 1954)

Unfortunately, I didn’t encounter such inspiring anecdotes until I’d grown well past the need for role models. (To paraphrase what a famous African-American actor once said to me: Role models are useful up until the age of 17. After which time, if you still need one, what you really need is therapy.) By that time, I had also come to realize other things about Louis Armstrong that made him seem even greater a hero than I was conditioned to believe as a teenager. His well-publicized rancor with the U.S. government over President Eisenhower’s reluctance to send federal troops to Little Rock in 1957 to enforce school integration revealed a fiery militancy very much at odds with the jovial, hanky-brandishing persona that was the only Armstrong my generation knew.

Getting past that image was something that even my parents’ generation had to be talked into, given its too-close association of Armstrong with the hambone minstrelsy of a fading era. However warmly they may have felt towards Pops, my folks and their peers found it easy to dismiss him as, at best, Yesterday’s News. And if my parents weren’t going to guide me towards Armstrong’s example, my fellow baby-boomers were even less help. To them, Armstrong was Everybody’s Foxy Grandpa—always entertaining you with his sandpaper voice and cute expressions but lacking the raw aggression of James Brown, the stiletto-edge danger of Huey Newton and the sex appeal of any pop star of our era.

Let’s be plainer still: What the boomers believed at their worst was that Louis Armstrong was a prototypical sellout pandering to the crowds; an Uncle Tom. I never (I don’t think) went that far. But received “wisdom” of this magnitude was powerful enough to keep me from engaging Armstrong’s music, no matter how much of it came my way.

“Political correctness” was a concept whose usage was pretty much confined to Marxists when Armstrong died in 1971. But professing an informed fondness for Louis Armstrong and all he personified was something of a liability for young African Americans who in those Nixon years were being goaded to the barricades, literally and figuratively. Part of me accepts these circumstances because that’s the way it wuz in dem days. Most of me will always resent empty socio-political baggage put between a potentially nourishing life force and my unfulfilled self.

It wasn’t until four years after Armstrong’s death that the piercing clarity of his horn shattered my pre-fabricated resistance. It was the 1927 recording of “Struttin’ With Some Barbecue” included on the first edition of The Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz. Armstrong seized my attention and curiosity from the opening chorus with the kind of force that one imagines it had almost a half-century before on an earlier generation of listeners. That was the beginning of a long, happy re-acquaintance with King Louis during which I listened to all the majestic 1920’s recordings with fresh, revitalized ears (Three words. “West End Blues.” Go now and listen to it!) while reading whatever I could find about him. Throughout these years, I sought to make amends with his spirit. Many surprises awaited me on the journey.

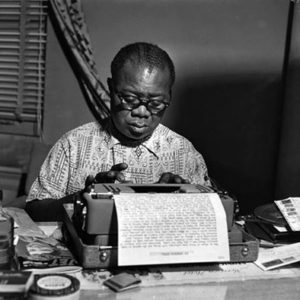

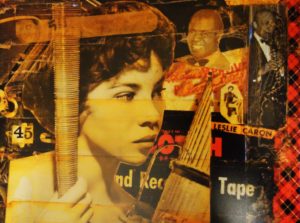

I knew of his disdain for modern jazz, especially the beboppers. What I hadn’t known about was his fondness for Guy Lombardo and rock and roll, his R-rated sense of humor (Three more words. “Tight Like That.” It should be on the same circa-1928 disc as “West End Blues. Seek. Find. Laugh.), the letters he wrote on the road or at home, the collages he made by hand and, most revealing of all, the anger at racism of all kinds that he concealed behind his amiable mask until it became necessary to let it loose (as it was when Ike was tardy with backup). The more I found out, the more enigmatic and mysterious I found this man who seemingly gave all of himself to his public.

Ossie Davis alluded to such chimeras in his on-camera testimony in Ken Burns’ series. As with many who came of age after Armstrong’s early breakthroughs, Davis had trouble getting past what he called “ooftah,” his name for the shucking-and-jiving stage antics that Armstrong deployed like a poker dealer. But when he’d seen Armstrong sitting alone off-camera during a shoot of Sammy Davis Jr.s 1965 movie, “A Man Called Adam,” Davis was moved by the intensity of Armstrong’s immobile expression to re-evaluate his opinion. Maybe, Davis thought, Armstrong was concealing lethal weaponry beneath that broad grin, ubiquitous hanky and gilded trumpet.

The way I feel now, I don’t care whether that horn, in Davis’ words, “could kill a man.” I just know that it’s taken longer than necessary to give Armstrong a break for whatever he was supposed to have done to African Americans and their self-image—and for me to figure out what I needed him for. Everyone else should try as well. After all, it’s his birthday.