Bill Conlin was a terrific writer and a dreadful person. He was larger than life and among the lowest forms of life. This is where things begin and end with him and I’d just as soon start here with how it ended since that’s what so many now think foremost about him while preferring to forget everything else.

On December 20, 2011, less than six months after he’d accepted the J. G. Taylor Spink Award from the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown for lifetime achievement in sports writing, Bill Conlin abruptly retired from the Philadelphia Daily News when its sister paper, the Inquirer, published accusations from three women and one man that he’d sexually molested them as children during the 1970s. (One of the alleged victims, a prosecutor based in Atlantic City, was Conlin’s niece.) Three more people later made similar accusations.

From what I’ve read in several outlets, it’s clear that as horrific as the crimes were (and because the statute of limitations had long expired, he was never formally charged), the manner in which he was said to have intimidated, browbeaten and otherwise manipulated children and their parents to remain silent for so long was as despicable as the crimes themselves. Worse – but then cover-ups often are.

Conlin, protesting his innocence to the end, banished himself to Largo, Florida where he spent the remainder of his days in debilitating seclusion before his death in January 2014, at 79, from kidney failure. Among its many unbearable-in-retrospect outcomes, Conlin’s steep, rapid and mortifying fall from grace was a hard kick in the collective stomach of those of us who consider ourselves proud veterans of the Philadelphia Daily News, for which he’d been among its more glittering ornaments.

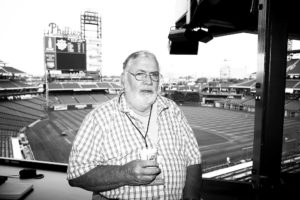

During my own tenure at the “People Paper,” accounting for just nine of the forty-five years he’d spent there, I saw Conlin in person just once. It was sometime in the mid-1980s when he’d come to pose for photos with other Daily News stars for a magazine article about the paper. His appearance in broad daylight was a rarity, given the wee hours he kept at work and at leisure, along with the fact that he did practically all of his writing from his New Jersey home.

Those of us on the clock that afternoon peppered his Brobidngnagian aura with smart-to-semi-stupid questions about baseball, its content and discontents. He didn’t mind answering any of them. In fact, one had the feeling that the only thing he loved more than baseball was talking at length about baseball, sharing clubhouse gossip about the Phillies and their National League antagonists, dropping the occasional dime on a general manager or player for this or that off-the-books peccadillo and theorizing with abandon on any number of topics whether it was the Battle of Balaclava or Larry Bowa’s endless war on third-base umpires.

Yet for all his rangy intelligence and lordly indulgence, Conlin also gave off the unsettling aura of one of those broad shouldered smartasses you remembered from high school who out of sheer boredom would body-slam you against the lockers while you were on your way to class, shouting loud enough for the hall monitors to hear that he was sorry about your chipped tooth, but you were in his way and made him late for chem lab, so later, gator!

Hence my first and only one-on-one impression: A bully; bright, expansive, sophisticated, but a bully, nonetheless.

And, as it turned out in the end, much worse besides.

Almost ten years will have soon passed since the disclosures and Conlin’s soul still drifts in a Negative Zone, from which there is neither a chance of, nor inclination towards recovery or escape.

However…

It’s March again. And as usual around this time of year, I am engaged in my annual ritual of poking and gleaning my library of baseball books as a way of psyching myself for the forthcoming season. One of those books I always turn to is Batting Cleanup, Bill Conlin, an anthology of Conlin’s newspaper writing collected and published in 1997 by Kevin Kerrane. I remember buying the book that year on my one and, thus far, only visit to Cooperstown and that it was at or very near the peak of Conlin’s national fame as resident curmudgeon on Dick Schaap’s Sunday-morning panel show The Sports Reporters on ESPN.

There are those who insist that reading old newspaper articles is about as useful or as transformative as reading old newspapers – which is to say not much. And there are those like me who avidly read old newspaper articles, between hard covers or not, because, at their best, they can convey the immediacy of a past moment more vividly than a work of history conceived years after the fact. It is like that with Batting Cleanup: Conlin’s deadline artistry was such that one of his columns can, like a “golden oldie” pop hit, take you back to the moment they were new, fresh and in the air, most especially when baseball was the topic.

I don’t want to stretch the point too much; in some ways I am as conflicted about Conlin the writer as I am towards the thorny pathos of his personality. Even during my time in Philadelphia, I never shared in the all-but-universal acclaim Conlin received on the Phillies beat as Earth’s Mightiest Baseball Writer. My own tastes in newspaper baseball scribes in the seventies and eighties tended to favor the Boston Globe’s super-grinding hard rocking Peter Gammons and the Washington Post’s wry and graceful Tom Boswell.

But however impressive were Gammons’ and Boswell’s respective strengths as well as those of countless others who regularly covered baseball over decades, there is general agreement that Conlin had few peers (if any) in being able to break down the nuts and bolts of any game and lay them out for readers who, having already heard the score on radio or TV, looked for something edgier and more “inside” from an informed, idiosyncratic spectator. Unlike Gammons, Boswell, the New York Times’ George Vecsey and other more urbane sportswriters roughly in his generation, Conlin cast his lot with a scratchier, more combative tradition, extolling both Jimmy Cannon and Dick Young as his role models. These influences made Conlin a sometimes unwieldy, but often compelling compound of street corner poet and barroom brawler – the latter of which he literally, habitually, notoriously was.

His single greatest column, since I now have the floor, was his 1970 sendoff to Connie Mack Stadium, written in sorrow, bile and reverie, from which it is all but impossible not to quote at length:

“Connie Mack Stadium is an old woman dancing nude at the Medicare Senior Prom. You know what she might have been , but tonight she is an obscene accordion of yellow flesh.

“Connie Mack Stadium is a joke played by a 1909 high school class in Architecture. At its best, the architectural style could be described as St. Louis World’s Fair Lavatory. It makes [Philadelphia] City Hall look like the Palace of Versailles.

“Connie Mack Stadium is the adrenaline pumping, the terror rising as furtive footsteps draw closer at 1 a.m. after a twi-night double header.

“Connie Mack Stadium is four flat tires on Smedley Street. Next time, you’ll let that kid watch your car for a dollar. Maybe next time you’ll stay in the suburbs and mow your lawn…

“Connie Mack Stadium is a night under a Lehigh Avenue moon, first discovered by the noted astronomer [longtime Phils broadcaster] By Saam. It is Saam making the game come alive for those of you at home scoring in bed. It is Rich Ashburn in his floppy tennis hat, preceded by a decade of floppy singles.

“Connie Mack Stadium is a [Richie] Allen drive searing the night, the wonder of it leaping a tall sign and muting the boobirds. It is Allen tracing out “Oct. 2” in the first base dirt while Bowie Kuhn blanched. It is a lone couple necking in the upper deck in rightfield.

“Connie Mack Stadium is an old man sitting in erect in a sun-drenched dugout. It is where the organ lady quit one night, to be replaced by years of scratchy Guy Lombardo records.

“Connie Mack Stadium is the lengthened shadow of a man sliding finally to rest. A small step for any other city, a giant step for Philadelphia.”

This is what you could read beneath Conlin’s byline somewhere in October, 1977, the day after what was then a prototypical Phillies Phold in crunch time:

“Dusty Baker hit a tough chopper to third, and Mike Schmidt pounded on the wicked short hop like a jaguar running down a rabbit.

“That was one out in the top of the ninth, seven straight ground balls thrown by Gene Garber . And 63,719 fans were on their feet , a shrieking chorus that all afternoon had roared with the blood lust of a Roman Coliseum mob rooting for the lion.

“Rick Monday bounced out to Teddy Sizemore. The Vet throng was chanting ‘DEEFENSE.’ Eight straight ground balls by Geno. Game three was history. One more out, Geno baby, and this was a 5-3 Phillies victory. The Dodgers had coughed up two eighth-inning runs to go with the three the crowd and plate umpire Harry Wendelstedt had bled from starter Burt Hooten in the second.

“The Dodgers were down to their suspect bench. Ancient Vic Davallio hauled his well-traveled bones to the plate, more wrinkles on his leather face than there were base hits left in his bat. On deck was Manny Mota, 39 years old, one final straw for Tommy Lasorda to clutch at should Davallio reach first base.

“Thus began the shortest, most devastating nightmare in the history of a town steeped in an athletic tradition of flood, fire and famine, a place where down seemed like a long way up.”

It doesn’t matter whether you had a dog in this race (though Conlin’s constituency obviously did). These graphs put you in that park with a sweep and intensity that no digital feed can match.

Here’s another lead from 1981 recounting a night when the Cardinals “chain-sawed” the Phillies 11-3:

“Last night, the Phillies outfielders spent more time in the alleys than the Guardian Angels. And by the time the Cardinals savaged Dickie Noles for five ninth-inning runs, the infielders were suffering from advanced windburn. When they weren’t ducking bullets, Larry Bowa and Manny Trillo were sprinting to the outfield to take relay throws from the warning track. Pete Rose spent so much time crouched at the cutoff position, he could have been designated an historic landmark.”

Somewhere between these two calamities, the Phillies won their first “world’s championship” in 1980 and this was how Conlin chose to end his back-page lead story of the sixth and final game:

“[T]o paraphrase William Butler Yeats, 97 years of stony sleep were vexed to nightmare by a rocking ballpark. And this rough beast of a ball club slouched towards JFK Stadium to be reborn.”

A risky conceit for a baseball beat writer to drag Yeats from left field, so to speak. But Conlin’s copy often dared going to places it didn’t belong. He could be both antic and lyrical in the same paragraph with little strain or clutter showing in the result, “antic” and “lyrical” comprising an unruly juxtaposition of terms that fit neatly over the collective personality of his tabloid home.

It may be a kind of chicken-egg question as to how much the Philadelphia Daily News’ house style, to the extent there was one, empowered Conlin’s style and those of others. Clearly, his presence was large enough to have encouraged those of us who wrote in different sections of our paper to be as brashly erudite as he was. Along with the other members of the Philadelphia Daily News’ storied sports staff (and such front-of-the-paper columnists as Pete Dexter and This Guy), Conlin’s way of writing influenced our own and those of us affected/infected with its swagger forged our own variations on his pugnacious energy.

Again, I don’t want to overstate things: There was in Conlin’s writing a streak of cruelty poking through the crustiness of his persona that, as with his idol Dick Young, could egregiously bruise and bloody someone who made him angry. I prefer instead to acknowledge those bluff interludes of tenderness he could summon, as he did for the passing of Arthur Ashe in 1993: “…when a genius dies, you grieve for the acts of genius left undone…Black or white, rich or poor, gay or straight, athlete or couch potato…we are all terribly diminished.”

Still it’s difficult, if not impossible to reconcile my admiration of Conlin’s “termite art” (and pantheon movie critic Manny Farber, if he’d read any Conlin, would surely place him in that category he’d coined) with the craven squalor of his crimes against children. But I haven’t in the years since Conlin’s death been able to abruptly or casually “cancel” such prose from my life because, whether I like it or not, it’s part of swarm of voices that helped me create my own. He was never as great a professional role model for me as others I’ve met along the way. And I never knew him well enough to regard him, abstractly or otherwise, as even an acquaintance. But I reject the idea that his sordid deeds inflect his work with toxins that might somehow infect me with his same disease if I were to pick up a clipping or a chapter with his name on it.

We are all left with the good and bad of what others leave behind and as furious as I am on behalf of his victims and those he bullied into keeping their pain under wraps, I can, along with the rest of you, only move into the baseball seasons ahead with recrimination, regret and, every once in a while, sadness over the deep scars ruining what could have otherwise been an awesome legacy.