So this is what happens when you’re double-sequestered by piles of snow from a big, beautiful nor’easter along with the ongoing threat of pandemic – and NO damn vaccines available and accessible within miles of where you are. You hear a Herbie Nichols record and think to yourself: this is exactly what makes sense right now.

It wasn’t the music itself that brought me back to Nichols so much as a YouTube video posted by Jason Moran a few weeks ago featuring a rare WBAI radio interview with Nichols from 1962, which meant it took place on Mait Eady’s “The Scope of Jazz” show when the nonpareil pianist-composer had months left to live before dying, at 44, in April, 1963 from leukemia.

The conversation is, therefore, a blessed gift from the universe. It retains Nichols’ lovely and lucid speaking voice and affirms what writers like A.B. Spellman have attested about his warmth and wide-ranging intelligence. One also infers that if Nichols was getting interviews like these, then the relative obscurity he’d faced after his mid-1950s run of albums for Blue Note and Bethlehem may have shown signs of dissipating at last and that listeners were ready to engage what once seemed even to the adventurous an eccentric body-of-work.

It’s only towards the end of this fascinating interview, with plenty of his compositions and recordings weaved into the mix, that you hear Nichols’ frustration with being marginalized in comparison with fellow modernists such as Thelonious Monk, who was by the Kennedy years enjoying a burgeoning nationwide vogue thanks to his contract with Columbia Records. Nichols aims his irritation, ever so gently, at jazz critics, who he wishes had more grounding in formal musical education and could therefore better appreciate, or at least begin to understand what he’d been trying to do. Eady, sounding somewhat flustered, confesses to Nichols that he has no musical training, prompting Nichols to suggest, with all the geniality at his disposal, that he should consider getting some.

In my time as a jazz journalist, I used to hear this a lot from musicians who believed, not entirely without justification, that we were getting in the way of their transactions with the audience by not being able to satisfactorily explain the technical nuances of what they’re doing. Once, early in my jazz reporting tenure at New York Newsday, I was taking notes at a Carnegie Hall concert when I glanced across the aisle at a competitor for another daily who seemed to be scribbling harder than I was. I tried to match his intensity before leaning close enough to see what he was writing: not words, impressions and titles (as I was), but actual musical notation! Like…notes, key signatures, clefs, man!

I slunk into my chair, despondent, believing myself to be an imposter and wondering what the hell I thought I was doing here. But I still had a deadline to meet and went back to whatever it was I was doing.

In time, I got over this by eventually reminding myself that my job, in the end, wasn’t to deconstruct technical information well enough to satisfy the demands of those I was writing about. My job was to report back to readers how it sounded to me and, in doing so, convey to those who weren’t at Carnegie Hall that night or any other venue on any other engagement what it felt like to be there. My readers and, for that matter, the musicians on stage were just going to have to trust that I’d listened to enough jazz, done enough background research and cultivated my instincts sufficiently enough to tell my story to others who, to varying degrees, were as familiar with, or more to the point, as interested in the subject as I was.

That was all. Maybe it wasn’t enough for some. But my readers trusted me for a long enough time to put up with my reporting. So I must have done something right.

And while I understand the frustration of musicians like Herbie Nichols, I now believe that having critics with the keenest first-hand musical knowledge try to mediate their art with the public doesn’t necessarily guarantee a bigger, more receptive audience. Even scholarly musicologists, I submit, can be overly influenced by conventional wisdom and they can be just as oblivious to Something Totally New as whatever musicians imagine to be the clueless masses. It’s as true with all art: movies, books, paintings, dance and fashion. There are whole eras where it’s hip to be square, or at least, safe. Even “square” can catch people off-guard when they’re expecting something more rhomboid or triangular. If that makes any sense…

Whatever. It’s just a pleasure to be able to argue with a long-lost master in absentia. And as long as we’re here, in case you aren’t aware of who Herbie Nichols was and why he mattered to so many of us who still exult in modernism’s resilient wonders, here’s an entry I wrote for a long-defunct biographical jazz site. It also places before the court an example of how a relative “amateur” in formal musicology tries explaining genius to whomever shows up to listen. Consider this, also, a sideways homage to Frank Kimbrough, a keeper of Nichols’ flame and a great pianist in his own right, whom we lost sometime close to the start of this new, presumably better, year.

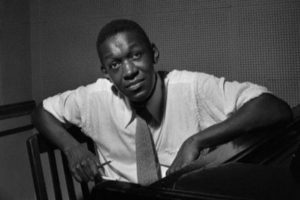

NICHOLS, HERBIE (HERBERT HORATIO) Jan. 3, 1919-April 12, 1963

Herbie Nichols’ compulsively inquisitive spirit lives within every session player struggling to cultivate an individual sound within the din of the marketplace. Nichols spent most of his career working in bands whose music wasn’t nearly as idiosyncratic or progressive as his was. If the stars had been better aligned in his favor (or, as some of his friends have suggested, he was less self-effacing), Nichols would have been regarded in his lifetime as a modern jazz pianist as innovative as Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk. Yet it is only in the years since his death, at 44, from leukemia that Nichols has slowly achieved the stature he deserves. He has seduced subsequent generations of listeners and musicians with his angular melodies and rhythmically-sculpted harmonies.

The son of emigrants from Trinidad and St. Kitts, Herbie Nichols was born Jan. 3, 1919 in New York City’s San Juan Hill section in the West 60s. At age 7, he moved with his family further uptown to Harlem where, two years later, he began studying piano with a teacher who stressed classical training. As a youth, Nichols was said to be introspective and fun-loving, good at checkers and chess, steeped in books (a favorite author, according to his friend, trombonist Roswell Rudd, was the Russian Nikolai Gogol) and attracted enough to the popular music of his teen years to play jazz with a high school combo.

His first professional gig came in 1937 with the Royal Baron Orchestra, led by saxophonist Freddie Williams and featuring bassist George Duvivier. A year later, Nichols began working regularly at Monroe’s Uptown House which, along with another Harlem venue, Minton’s Playhouse, would become legendary in jazz lore as an incubator for the modernist upheaval in jazz music. In later interviews, Nichols would say he was both stimulated and put off by the hothouse competitive atmosphere generated by the virtuosi who would invent bebop and other post-swing genres. He was unhappy with what he later characterized as a clique mentality among the musicians who worked at Monroe’s and Minton’s. The critic Leonard Feather, in liner notes written for one of Nichols’ 1955 Blue Note albums, recalled Nichols being “pushed off the piano stool” at after-hours jam sessions by less-talented players.

He was drafted in 1941 and served 18 months in the Infantry with little opportunity to either take part in battle or play music. When he returned to New York in 1943, Nichols was unable to connect with the burgeoning bebop movement, playing mostly with rhythm-and-blues or New Orleans-style bands. Among his more prominent employers from the mid-1940s through the early 1950s were Danny Barker, Hal Singer, Illinois Jacquet, Snub Mosely, Arnett Cobb, Edgar Sampson and John Kirby. Through it all, Nichols was also struggling to find his way as a composer, sending off musical pieces that were either neglected or rejected by publishers.

Then in 1951, Nichols met Mary Lou Williams, a pianist attracted to the kind of quirky, insurgent music being written by Monk and his contemporaries. After hearing Nichols play some of his compositions, Williams recorded three of his tunes, “The Bebop Waltz” (which she re-titled “Mary’s Waltz”), “Stennell,” which she dubbed “Opus 2” and “At Da Function.” (Nichols’ flair with titling his own work would become apparent as he recorded as a leader, though his most famous piece, “Lady Sings the Blues” was originally dubbed “Serenade,” until Billie Holiday heard it and was so taken with the melody that she wrote her own lyrics to the tune, whose new name was also the title of her 1955 autobiography.)

Nichols continued to work mostly for traditional jazz and swing bands throughout the northeastern United States while auditioning for his own club dates and recording sessions. Blue Note Records co-owner Alfred Lion remembers Nichols being especially persistent for more than a decade in asking for a chance to record his own music. Lion gave Nichols his shot. In May and August, 1955, Nichols recorded with bassist Al McKibbon and drummers Art Blakey and Max Roach. He recorded another session the following August with Roach and bassist Teddy Kotick. Two 10-inch albums were released by Blue Note from those sessions and were immediately hailed by critics, though relatively neglected by the public. The same outcome greeted his only other album as a leader, Love, Gloom, Cash, Love, released in 1957 by Bethlehem to glowing reviews and anemic sales.

Nichols went back to playing Dixieland music for dough, though in his latter years, his recordings had acquired cult status among an emergent generation of progressive musicians, including Archie Shepp, Cecil Taylor, Buell Neidlinger and Roswell Rudd. Nichols’ reputation as a composer and innovator was still a well-kept secret and his frustration only deepened with every throwaway gig, every indifferent audience he faced. “He seemed to be dying of disillusionment,” wrote A.B. Spellman, the critic and historian whose 1966 book, Four Lives in the Bebop Business, helped set in motion Nichols’ posthumous restoration. “He knew his worth, but it seemed as if nobody else did.”

Perhaps only a sensibility as independent, contemplative, wistful and tenacious as Nichols could have forged such alluring, yet provocative music. As with his friend and rival Monk, Nichols plays and writes with calculated indifference to melodic and harmonic convention. His main themes, as with the aforementioned “Lady Sings the Blues”, are accessible and even “hum-able.” Yet his variations often spread themselves in eccentric patterns within, around and through the song’s intervals. Listen, for instance, to his rendition of “The Gig” on his Blue Note collection and you’ll hear phrases repeated, stretched, smashed and re-shaped along a seeming riot of tempo shifts that never veer too far from the rhythmic core. You sometimes wonder whether the piano is bracing up the rhythm section or vice-versa. Either is plausible, given Nichols’ affinity for harmonies that keep time as much as they play with it.

The title track from Love Gloom Cash Love is as melancholy as acerbic as its title would lead you to believe. Yet its progression owes as much to classical music as it does to Tin Pan Alley song structure. Nichols’ sense of mood, drama and narrative timing can be found in just about any one of his compositions, such as “House Party Starting,” which trumps the sense of anticipation aroused at the start for the eponymous party with what Nichols, in liner notes he’d written for one of the Blue Note albums, “grave and silent doubts as to whether there is really going to be a parry, whether there is going to be lots of fun.” Contrasts stalk a Herbie Nichols composition as disappointment often trailed his life’s achievements.

After Nichols’ death, a host of musicians from Rudd, Neidlinger and Shepp to John Coltrane, Steve Lacy and Misha Mengleberg performed and enhanced his work in order to help fix his name in the global jazz repertoire. One can also hear Nichols’ influence in an eclectic assortment of younger piano talents, notably Geri Allen, Jason Moran and Frank Kimbrough, who in the 1990s helped spearhead the Herbie Nichols Project, an ensemble of musicians dedicated to performing Nichols’ compositions, including those never before performed, though ensconced in the Library of Congress.

RECORDINGS

Herbie Nichols: The Complete Blue Note Recordings (1955-6) (Blue Note), 3 Discs.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Spellman, A.B., Four Lives in the Bebop Business, 1966, Limelight paperback

Davis, Francis, “The Mystery of Herbie Nichols” from Outcats: Jazz Composers, Instrumentalists and Singers, 1990, Oxford University Press.