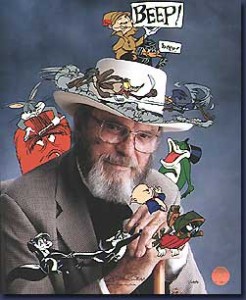

Today is Chuck Jones’ 100th birthday and they’re having a party for him out in Glendale, California tonight to mark the occasion. That’s great, but I thought an even-broader fuss would be made over one of the greatest American filmmakers. (And don’t you dare say he “only” made cartoons, which is somewhat like saying Chopin “only” wrote piano pieces.) If that clause requires justification, consider that three of Jones’ Warner Bros. shorts were among the films chosen by an army of critics and filmmakers in the recently-unveiled 2012 Sight-and-Sound poll of Greatest Films Ever Made.

If I’d had a ballot, I’d have made sure I put a Chuck Jones film on it. But I’d have a helluva time picking one. The three I’d found on the S&S list – “Duck Amuck” (1953), “What’s Opera, Doc?” (1957) and (a mild surprise) “The Ducksters” (1950) – surely qualify. But that leaves out so much: “The Draft Horse” (1942), “Tom Turk and Daffy” (1944) (“The yams did it!! The yams did it!!!…), “The Eager Beaver” (1946), “Mouse-Wreckers” (1949), “Long-Haired Hare” (1949) (“What do they do on a rainy night in Riiiio?….”)“The Scarlet Pumpernickel” (1950), “The Rabbit of Seville” (1950), “Two’s a Crowd” (1950) (The first appearance of the floppy-eared puppy whose yapping sends Claude Cat to the ceiling), “Chow Hound” (1951) (a personal favorite precisely because it freaks so many people out), “Bully for Bugs” (1953), “Duck Dodgers in the 241/2 Century” (1953)….

Sheesh! And even this leaves out so much: All of Pepe Le Pew, Marvin the Martian, Wile E. Coyote (and his Arcadian counterpart Ralph Wolf), that kitten-loving lummox Marc Anthony, the unwanted mongrel Charlie Dog, Sam the Sheepdog, the Road-Runner, Sniffles, Hubie, Bert and assorted other mice.

And why stop with the Warners Bros, stuff? There’s this Oscar winner from his MGM period that holds up as well as any full-length feature of comparable ambition. (I’ll think of one, eventually):

I’m not sure there’s more to be said for this and other great, small works of Jones — except maybe to speculate that the reason why these keep killing us from one century to the next can be found in their simplicity of intent. Mack Sennett, the silent comedy impresario who likely helped Chuck Jones the small boy become Chuck Jones the artist, once deflated solemn critical analyses of his productions by writing, “We merely went to work and tried to be funny.” Jones often said similar things in his own interviews, but as “Dot and the Line” indicates, he was also intent on sliding low comedy to higher ground. Sometimes, as with Chaplin, he was obvious about it; other times, as with Keaton, he was sneaky with it. (I preferred the sneaky stuff, which is to say, most of the Warner stuff from the 1940s and 1950s. )

Either way, he made it look easy. So easy, in fact, that no one today seems to be able to do it as well. Which is not his fault.