I often think Norman Mailer would have been better remembered on his 100th birthday if he’d used his engineering degree from Harvard to write science fiction. Assuming he’d also retained what he’d absorbed from Dos Passos, Tolstoy, Stendhal, Hemingway, James T. Farrell and Rafael “Captain Blood” Sabatini, Mailer might have melded such anomalous elements with the influences of Kafka, Verne, H.G. Wells, Olaf Stapleton, Karel Capek, and the pulp magazine prodigies to lift the SF genre to a higher literary standing – and in the process learned not to be so intimidated by the contingencies of plot. Hints of this furtive lyricism with technology can be found throughout the second half of Of a Fire on the Moon, his freewheeling, undervalued reflections on the 1969 Apollo 11 lunar landing. (Check out his chapter on “The Psychology of Machines” and tell me if you don’t think Arthur C. Clarke wouldn’t have envied such virtuoso empathy with the mechanical.) If he’d followed this aspect of his muse from the start, Mailer could have been the proto-socialist yang to Robert Heinlein’s libertarian-right yin, an Americanized Stanislaw Lem, Philip K. Dick with the sex, drugs, and paranoia ramped up…

Then again, forget it. For better and worse, we got the Norman Mailer he and we likely deserved. If he’s largely neglected and considered irrelevant in the 21st century, it’s mostly because he made himself so visible in the 20th. In his Advertisements for Myself, the 1959 miscellany that jump-started his literary reputation, Mailer proclaimed that he “was imprisoned with a perception that will settle for nothing less than making a revolution in the consciousness of our time.” Of the myriad risks Mailer took with this impulse, however, the biggest was making himself so unavoidable in his own time that his work wouldn’t endure in public renown too far beyond it.

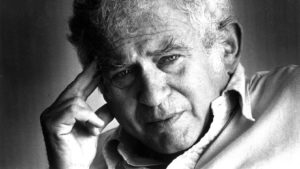

On some level, he asked for it. For much of his lifetime (he died in 2007 at 84), Mailer was not only a household name as a novelist, but he was also a provocateur, an enfant terrible whose public displays of rancor and violence often overshadowed his literary output. He’d stabbed his second wife Adele Morales at a November, 1960 party celebrating his impending candidacy for major of New York City. (He didn’t run for mayor until 1969 and finished fourth in a field of five in that year’s Democratic primary.) He behaved badly on television, made independent movies (in one of which he bit Rip Torn’s ear), sealed his legacy as an anti-feminist after publishing The Prisoner of Sex in 1971 and summarily got into a shouting match at Town Hall with feminists on stage and in the audience. (That was all caught on film, too.)

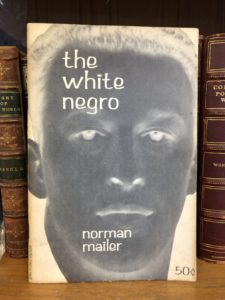

Even in absentia from the known world, Mailer’s still causing trouble. A year ago, there were online reports that Random House cancelled plans to publish a collection of Mailer’s political writings because “a junior staffer” objected to the title of Mailer’s 1957 essay, “The White Negro.” The publisher, Mailer’s son, and agent denied the reports. But it was a straw fire that made Mailer conspicuous once more and aroused this thoughtful evaluation from Darryl Pinckney, an African American novelist and journalist.

My own relationship with “White Negro” is complicated and all but sums up how I feel about Norman Mailer to this day. When I started reading his work as a teenager enraptured mostly with his journalism (about which more later), friends, Black and White alike, kept urging me to read “The White Negro” before I read anything else. So, I tried. And tried. And tried again. And I couldn’t get past the first, to me, impenetrable paragraphs of that chapbook edition that made the rounds in those days. I tried again when I finally got around to Advertisements for Myself and even then, I ended up sort of going around it as though it were a dead oak that keeled over in the middle of an intersection.

Indeed, it wasn’t until deep into my forties or maybe even fifties, that I managed to read it all the way through and decided that the reason I couldn’t push my frontal lobes past “White Negro’s” first page was that it was totally, ridiculously alien to my own knowledge of what it meant to be Black or, for that matter, to be Hip. In short, I thought it was too absurd (again, not the way he’d likely intended) to be taken seriously as anything more than an anxious glandular discharge. I couldn’t even get angry with it the way Black people did (and still do) because I think it’s too dumb to get worked up over, even after reading Mailer’s subsequent writing about African Americans, as when he argued against Ralph Ellison’s conception of “invisibility” in Black Americans, saying that we were, in fact, the MOST visible people in America. “That’s not how he meant it, dammit!!” I always shouted back — though in his typically adroit sussing-out of individual psyches, Mailer did correctly perceive the depths of anger simmering beneath Ellison’s patrician scholar’s patina.

(And while we’re passing by Advertisements, what has occurred to me in recent years is that his grandiloquent pastiche of stories, novel fragments, reviews, polemics, and autobiographical spritzing can now be viewed retroactively as a precursor to the blog site or Substack page. I can’t possibly be the first one to notice this, but it would be Very Mailer of me to assume that I am.)

You could always count on Mailer being spectacularly wrong when trying to take History’s heartbeat. (I read somewhere that Marina Oswald, no less, was dryly amused by Mailer’s aspirations to be America’s Tolstoy.) But he was so much better with the human than with cosmic than most give him credit for. That was why I kept faith with him even when he self-sabotaged in public and in print.

Besides which, I owe him too much, even if I haven’t – and likely won’t – read every single book he’s written.

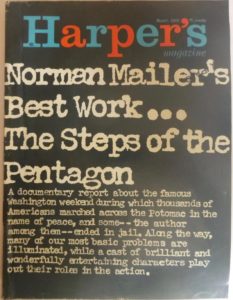

I remember the anticipation accompanying a magazine article with Mailer’s byline about a major event that, though it happened months ago, was made fresh and new again by his freewheeling imagination, and flamboyant prose style. We all knew what happened at the 1968 political conventions, Ali-Foreman in Zaire, or the Apollo 11 moon mission. But some of us looked to Mailer for deep, wide dispatches from beneath the surface of things, whether dragged from within the subconscious (his and others’) or projected from the outside. This process allowed him to dig up insights or angles that we either dimly suspected or couldn’t perceive in the moment. At its most lucid and vivid, the prose could lead you in the dark towards a light switch you didn’t know was there. Whole continents could be evoked by this style, as in this lead paragraph to the second section of Miami and the Siege of Chicago from 1968:

“Chicago is the great American city. New York is a world capital and Los Angeles is a constellation of plastic. San Francisco is a lady. Boston has become Urban Renewal. Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington wink like dull diamonds in the smog of Eastern Megalopolis and New Orleans is unremarkable past the French quarter. Detroit is a one-trade town. Pittsburgh has lost its golden triangle. St. Louis has become the golden arch of the corporation, and nights in Kansas City close early. The oil depletion allowance makes Houston and Dallas naught but checkerboards for this sort of game. But Chicago is a great American city. Perhaps it is the last of the great American cities.”

Paragraphs like this made me want to write paragraphs like this; also, pages and whole books. It’s an example of what Joan Didion was talking about in her review of Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song (1979) when she wrote: “It is a largely unremarked fact about Mailer that he is a great and obsessed stylist, a writer to whom the shape of the sentence is the story.” Maybe that’s why I go back to Mailer’s sentences more often than his books, though I’m one of the few people I know who’s read The Naked and the Dead three times, most recently just three years ago. Though it made history in its time as a contender for Best World War II Novel by an American, Naked and the Dead is, I believe, better viewed as one of the very last novels of the Depression (its flashbacks to the past lives of its soldiers) and among the first to intimate the coming socio-political tumult set off by the Cold War. And even though this once phenomenal best-seller has been somewhat undervalued compared with Mailer’s other work (by Mailer, too) because he hadn’t yet found the “voice” he achieved in Advertisements, the novel’s accumulation of raw details, its depictions of dread, drudgery, and the physical sensations of combat can now be seen as nascent signs of the gifted reporter Mailer would become. (A new edition of the book, published by the Library of America, includes letters Mailer wrote home from the Pacific Theater to his first wife Beatrice, which taken together come across as a working notebook for the novel.)

Mailer wasn’t as big on baseball as he was on boxing or football. (You know, the violent sports.) But as with great sluggers like Ruth, Mantle, or Reggie Jackson, Mailer’s swings and misses were as compelling to watch as the home runs, even when the odds were against him. At times, he could be embarrassing, abusive, or thin-skinned; at others, he could be magnanimous, urbane, and warm-hearted. Mercurial as Mailer was, there were two things you could always count on: his self-deprecating humor and his irrepressible candor. You could get mad at him. But you always believed what he said, even when he was wrong. And it was part of his grace that he could cop to being wrong and move on. In fact, being “right,” whatever that meant, didn’t seem as important to Mailer as maintaining an intensity of focus on one’s interior life and a constant, even heedless surge of energy towards acting on what one discovers from such self-scrutiny. This, I now think, was what Mailer meant when he kept using the word, “existential,” though I still don’t know if that’s a precise definition of the word.

Mailer’s honesty, I think, also compelled him to bend and reshape journalism the way his beloved Picasso transfigured representational art. Acknowledging that “objectivity” is a myth, Mailer leaned hard into subjectivity, eventually making himself the protagonist of his own account of actual events. Conventional wisdom still asserts this makes such accounts suspect, but to this day, the intensity of Mailer’s vision of the actual framed with the idiosyncrasies of his personality somehow makes you trust his version of the Pentagon March and the other events. Other reporters envied or hated him for getting away with this third-person approach. But as many found out when they tried it themselves, it could only work with Norman Mailer because he had the knack for simultaneously inflating and deflating his persona to the proper pitch as a trumpeter tests his tone and tempo.

And what does this have to do with the Self-Advertising Sexist Monster Ego of the Great White Male Bully Avenger of the 20th Century? While all the hype and bluster is hard to overlook and, in many cases, excuse, I doubt in the very long run it will matter. Because while I agree that much of the nonsense Mailer attached himself to is outmoded and of no use to anybody in the 21st, his renderings of the self, pressed hard by history as it happens, offer plenty of room for writers of all persuasions to probe further. If I were to let every dumb thing a smart man says and does get in the way of learning from his better side, I wouldn’t learn anything at all. In that spirit, I conclude with a memory of a graduate seminar on the history of nonfiction I taught at NYU sometime in the aughts. One of my texts was a collection of articles about the 1962 heavyweight bout between Floyd Patterson and Sonny Liston that included such journalistic heavyweights as James Baldwin, Jimmy Breslin, Pete Hamill, and A.J. Libeling. To this class of eight women and one (minority) male, I singled out Mailer’s “Ten Thousand Words a Minute,” his Esquire essay on the bout notable for its digression into the welterweight bout earlier that year between Emile Griffith and Benny “Kid” Paret that ended with Griffith savagely beating Paret into a coma from which the latter never recovered, dying ten days later. That traumatic event, broadcast live on network TV, aroused some of Mailer’s most lyrical and poignant reportage and when, towards the end of that semester, I gave the class the option of writing about any of the pieces we’d discussed throughout, most chose Mailer’s fight piece.

One way or another, the art always leaks through time’s cages. Fact, not theory.