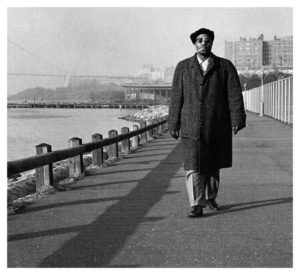

At the top of this man-made hill you will find the first poem I’ve finished in several years. It is also the shortest poem I’ve ever written. Because pride is a sin I will say only that I am happier with it than I expected. It may not have the Whitman-esque oomph of Muhammad Ali’s immortal “Me!/Whee!” It is also not entirely original since I borrowed the “Clonk!” from Jack Kerouac’s verbal approximation of a Thelonious Monk chord: “the clonk of [Monk’s] millennial piano like anvils in Petrograd.” The sounds of both “onk” words seem exotic on first encounter, but make perfect, even logical sense when joined together.

Much like the music Thelonious Monk made: The direct statement augmented by something you may not have expected.

Today (Oct. 10) is Monk’s 100th birthday and, though he’s been dead for 35 years, the “clonk” of fresh discovery abides in his life’s work. You can still trip over things you didn’t know before and, once you recover your balance, find yourself dancing along with its ramifications. Just as he did.

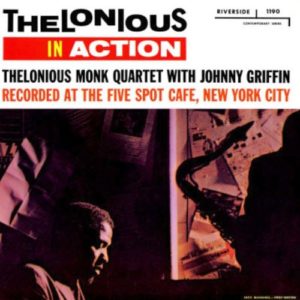

For example: I’m embarrassed to ask this out loud, but how did I manage to live this long and NOT get caught up, until now, in the whirlwind of Monk’s 1958 Five Spot sessions with Johnny Griffin? Some would-be smart-alecks think of Griffin as little more than the answer to a trivia question: Who was Monk’s tenor saxophonist between John Coltrane and Charlie Rouse? But the “Little Giant,” who died in 2008 at age 80, was hardly a footnote in anybody’s history.

Griffin was both paradigm and paragon of the hard-blowing Chicago saxophonists who roared through mid-to-late-20th century jazz music. Once Griffin reached peak intensity in his tone (bottom-heavy, reflecting his apprenticeship with rhythm-and-blues bands), he could spin chorus after breathtaking chorus of thick, fluid phrases, bulging with allusions to Italian arias, arcane folk melodies and Tin Pan Alley ditties as well as his own startling, vertically driven inventions. He may not have had Coltrane’s commanding austerity and fearsome range or Rouse’s dry wit and leathery brio. But what Griffin did have put the mercurial maestro of time and space in his comfort zone. And you can hear its overall effect resound happily in the performances compiled on the two-disc Thelonious Monk and Johnny Griffin: Complete Live at the Five Spot (2012, Phoenix Records). For those who now only have ears for vinyl, Thelonious In Action is apparently easily available and while Mysterioso, the other original Riverside LP covering these sessions, appears to be only available on CD.

I’d be happy to dwell on the specifics of Monk-Griffin, believing that I’d uncovered a whole expanse of untilled territory to cultivate. But I found out that none other than Dean Robert Christgau got there a good while before me and I am more than happy to yield my remaining time on this topic to him. And also to this.

Meanwhile, the Monk Century is getting its proper due from many precincts, the most attention by far going to the homage submitted to the marketplace only a few days ago by Joey Alexander, the preeminent jazz prodigy of the post-Millennium. He’s 14, they tell me, though I often wonder watching performances like this one how ANY 14-year-old carries himself with as much composure as he stretches the parameters of Monk’s “Evidence,” while respecting, even enhancing the piece’s spacious design. There’s a whole album of this stuff, Joey Live Monk (Motema) ready for downloading and it’s enough to for me to admit that whatever qualms I may have entertained about this kid beforehand have now gone away and hidden under an abandoned back porch. He is, as we sportscasters like to say, For Real.

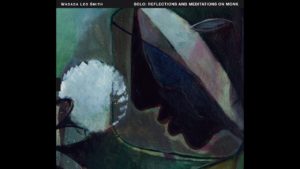

At the other end of the spectrum, in more ways than one, is Wadada Leo Smith’s Solo: Reflections and Meditations on Monk (TUM). At age 75, Smith is enjoying a bountiful winter of recognition for his life’s work as trumpeter, composer and bandleader, creating fresh contexts for orchestrated jazz and delivering plaintive, ruminative yet remarkably agile narratives on his horn. His liner notes acknowledge his considerable debt to Monk, “an inspiration that arcs straight across the structured invisible world.” Smith’s own art, whether alone or in groups, uses intervals as nimbly as the master. In his own renditions of “Ruby, My Dear,” “Reflections,” “Crepuscule with Nellie” and “Round Midnight” (all of which dare the bold and the thoughtful to bring their “A” Game), Smith seems to know precisely how to sustain spaces between phrases and, more important, when to come in hard, when to use stealth – and, in the case with “Nellie,” when to let its essential form do most of the work. He rounds out the album with original pieces, a couple of them stimulated by visual depictions of the pianist at work (“Monk and his Five-Point Ring at the Five Spot Café,” “Adagio Monk, the Composer in Sepia – A Second Vision”) and another, intriguingly speculative narrative (“Monk and Bud Powell at Shea Stadium – A Mystery”). Generations of jazz musicians have brought their adorations of Monk to his legacy’s front door. I doubt there is any other musician alive who could have presented anything as austere, adventurous and cordially challenging as Smith’s recital.

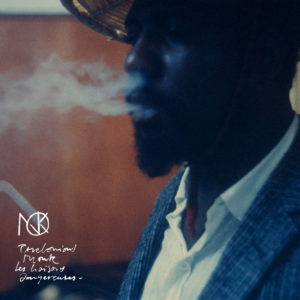

But perhaps the centennial year’s brightest jewel was unearthed earlier this year and, properly, it comes from Monk’s own archives. Les liasons dangereuses 1960 (Sam Records/Sag) delivers a substantial, previously unreleased account of a July, 1959 session of Monk’s quartet providing soundtrack material for Roger Vadim’s, modern-dress adaptation of the salacious 18th-century saga of seduction and betrayal among the French elite. Professional and psychological travails prevented Monk from providing original compositions for Vadim’s movie. (The liner notes by Robin D.G. Kelley, author of the definitive 2009 biography, Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original, are lucid and comprehensive.) Thus most of Monk’s contributions to the soundtrack are renditions of “Rhythm-a-Ning,” “Pannonica,” “Six in One” and his other familiar standards. The vogue for modern jazz being what it was in the late 1950s, most of the movie’s patrons found these songs to be properly hip ornaments to the spicy on-screen actions. Independent of the film, they present Monk in one of his happier, friskier states-of-being that overcame an especially arduous time in his life. The aforementioned Charlie Rouse and the then 22-year-old French tenor player Barney Wilen either traded off solos or fronted together on saxophone on these sessions while bassist Sam Jones and drummer Art Taylor provided backup. In this work-for-hire, one hears the stirrings of Monk’s 1960s period of wider popularity and greater opportunity. He plays here as though he knows that better times (relatively speaking) were around the corner.