Entries Tagged 'movie reviews' ↓

August 14th, 2013 — movie reviews

I never knew before seeing Blue Jasmine that so many people in San Francisco talk as though they lived in Bensonhurst all their lives. Nor, for that matter, did I know there was anyone under the age of, say, 50, who at this point in our history needed to go to something called “computer school” as a step towards taking on-line interior decorating courses. Then again, I bet I could tell Woody Allen a lot of things he doesn’t seem to know from watching his latest movie; for instance, that living in Brooklyn these days isn’t such a comedown from living in Manhattan. I mean, has he even noticed what a two-bedroom-one-bath apartment now goes for in Park Slope? Or even Bed-Stuy?

I’m aware that I now sound like all the knee-jerk Woody bashers who love finding fault with everything he does, inflating their contrarian capital off a reputation that hasn’t been nearly as impregnable as it was in 1979. What I mostly find admirable about Woody Allen these days (and it’s no small thing) is his tenacity in stepping up to the plate every other year just to see if he connects — and how far he can take the ball, whether the critics or the public like it or not. Don’t like that metaphor? How about the old saw of throwing a pile of you-know-what against the wall to see what shape it makes? However you look at it, this is what Allen chooses to do with his life now and if what sometimes results from his habit can be as satisfying as Vicky Cristina Barcelona or as haphazardly diverting as Midnight in Paris, then I’m thinking there are far less salutary ways for a 77-year-old man to spend his time.

Blue Jasmine has been wildly hailed, even by a few habitual Woody bashers, as being one of his best. I wanted to agree, partly because I prefer to cheer Allen on, but mostly because of what’s been proclaimed the movie’s principal asset: Cate Blanchett, playing a lapsed socialite driven to a slow-motion breakdown by the fiscal and marital cheating of her ponzi-scheming husband (Alec Baldwin)., Blanchett borrows much of the Day-Glo manic intensity she brought to her legendary stage rendition of Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named Desire to make her Jasmine a moist, quivering tower of jolting mood swings and ruined dignity. You stare at her face the same way you can be hypnotized by a wall-sized relief map of the world. All that’s familiar about her is every bit as exotic and mysterious as the places you didn’t know existed. Though she’s more formidable a physical presence than anybody else on-screen, Jasmine still teeters on the edge of sanity like a china figurine on the ledge of a shelf. You just want to be able to keep her from shattering when a fresh trauma jostles the ground beneath her.

It was only after the movie was over and she’d succeeded in breaking down my emotional defenses that I began to wonder whether Blanchett’s virtuosity amounted to a thinking-person’s special effect; something to “ooh” and “aah” over as you’re watching it block out the relatively threadbare thinking that went into the rest of the movie. Once Blanchett’s spell had dissipated, I even began to wonder how clever it really was for Allen’s movie to crib from the Tennessee Williams playbook to evoke the present-day reverb from the post-Millennial bust. It may flatter the professional and amateur spectators in the house to notice how Chili (Bobby Cannavalle), the earthy, volatile fiancée of Jasmine’s sister Ginger (Sally Hawkins) does or, mostly, doesn’t resemble Blanche’s bête-noire Stanley Kowalski. But that’s a lot different from responding to him as a human being. Even when he’s crying, Chili’s more a narrative device than a person. And this in turn places every other character’s humanity, even Jasmine’s, in doubt.

I’m willing to entertain the possibility that the artificiality of Allen’s tactics may be his point; that crises make us all, either wittingly or not, helpless characters in melodramas scripted by somebody else. However awkward or unearned the San Francisco milieu seems here (even the creepy-crawly dentist Jasmine fends off seems like someone whose office would more likely be based on Montague Street in Brooklyn Heights), it’s drawn out Allen’s better technical instincts. His cameras get more moodiness out of Ginger’s cluttered apartment than a less-experienced filmmaker would have dared. But the discordances in the storytelling, including the ones cited at the start of this piece, detract from such graces. I’m still not sure what to make of Jasmine’s harrowing rant in front of Ginger’s children beyond being another occasion to be riveted by the chromatic map of Cate Blanchett’s face. I’m mesmerized by the spectacle while wondering what it’s doing there at that moment.

There’s another performance in Blue Jasmine that’s just as transformative, maybe more so, than Blanchett’s. It belongs to Andrew Dice Clay as Ginger’s ex-husband Augie, whose marriage and life fell apart from investing his own modest fortune into a ponzi scheme. In his relatively few scenes, Clay conveys all the conflicting emotions of helplessness, bewilderment and unfocused rage common among those of us living in the aftermath of the burst economic bubble. I never thought I’d say this about anything to do with Clay, but I would pay to see a whole movie about that guy and I could even imagine Woody Allen making it – that is, if he could burst through his own bubble and see how the world beyond the East End and the Upper East Side truly lives now.

July 26th, 2013 — movie reviews

The creepiest, most phantasmagorical movie I’ve seen this summer has no zombies, vampires, aliens or mutants. Unless, that is, you wished to apply any or all of the above to characterize Anwar Congo, the Indonesian gangster and wannabe moviemaker profiled in The Act of Killing, Joshua Oppenheimer’s true-life chronicle of how Congo tried to make a glorified cinematic re-enactment of his country’s mid-1960s massacre of thousands of men, women and children suspected of communism. This enterprisingly deadpan inquiry into the banality of evil has slithered its way into our season of sun-and-fun to announce that not only is fiction dead, but so is black (as in absurdist) comedy. Why even bother trying to outgun Nathaniel West when Real Life can hand off an acrid fungus of a storyline such as this?

It helps not only to have reality be so obliging, but to have the collective vanity of killers comply with Oppenheimer’s audacious request. Then again, what is viewed as atrocity almost everywhere else in the civilized world is still embraced as glory by many Indonesians, especially the far-right paramilitary group Permuda Panacasila whose members swarm around the edges of this saga like mean orange hornets. This cluster of baby martinets owes its existence, apparently, to Anwar Congo, who before the failed 1965 coup that led to the Suharto regime, dealt in black market movie tickets and other relatively petty thuggery. For two years, Congo led death squads throughout North Sumatra in a bloody purge of those suspected of being communists, including several hundred ethnic Chinese from whom he and his goons extorted money in lieu of death. Of the estimated half-million-to-a-million murdered throughout the country in 1965-66, Congo figures he personally killed roughly a thousand, mostly by garroting.

In the here-and-now of Oppenheimer’s film, Congo seems less a monster than a foxy grandpa, a leathery coot who clearly loves movies, especially the American musicals and action films that he claims to have been prohibited from showing in theaters by those reform-minded folk briefly in power between Sukarno and Suharto. To the adoring delight of Permuda Panacasila’s younger zealots, he constantly translates the word, “gangster”, as “free man,” which, one supposes, is Congo’s way of justifying wholesale slaughter as a type of cowboy heroism, a celebration of freedom without democracy. (The latter of which is viewed by a paramilitary leader, while whacking golf balls, as a nuisance getting in the way of progress. With such sentiments still holding sway in Indonesia’s government, you understand why most of the movie’s credits, including a co-director, are accompanied by the name, “Anonymous.”)

Congo, our (Scot-)Free Man of Indonesia, is not merely willing to put together staged re-enactments of his violent, terroristic acts; he’s jumping-up-and-down anxious for the chance to show posterity the valor and glory of his murdering, torturing brigands, complete with song-and-dance numbers. One of his larger, more menacing henchman even agrees to pose in drag-and-makeup as a gang-rape victim. He reminds you so much of the late great Divine that you think there has to be somebody in this outfit who’s got some sense of irony here. But they’re as serious about their entertainment in contemporary Indonesia as we are about our own reality TV indulgences. (Irony, I guess, is something you can better afford in more democratic realms.)

Other citizens seem just as happy to perform as victims, predators or rabble in this historic epic. He even gets one of his ex-associates to fly in to help, though this associate looks as if he’s already been weighed down through the years with self-recrimination – a warning, unheeded by Congo, of what’s in store. The only things that seem to bother Congo, on viewing rushes of his movie have more to do with verisimilitude e.g. fashion. (He says he wouldn’t have worn white pants while garroting a victim as shown in one scene. Always dark pants. He never says why…and why should he have to?)

But a pall seeps into the process as one actor, who boasts about turning in his girlfriend’s Chinese father to the death squads back in the day, is helping re-enact a brutal interrogation. At first, he can’t quite get into character as a trussed-up victim who knows he’s going to die no matter what he tells his inquisitors. After a few takes, he starts weeping and sobbing as convincingly as the child performers who were earlier directed to wail over the brutal capture of their grandfather in their living room. It isn’t long before Congo, who casts himself as a movie exhibitor beaten by gangsters for refusing to yield to the autocracy, starts to feel a little queasy himself. By the end of this movie (not the one Congo’s making, but the one he’s abetting), this nausea literally erupts into an ugly, savage retching that, oddly (and perhaps appropriately), leaves no visible residue.

It’s possible that viewers will demand from The Act of Killing more emotional residue; or at least a less abstract approach to such wanton and still-unpunished mass murders. And yet, in being forced to take a more indirect approach to an historic atrocity, Oppenheimer’s film somehow manages to slice your nerves as deeply as any series of gruesome testimonies from survivors. Watching deformed memories deform society is infuriating. Yet this movie’s outcome represents one of the most perversely satisfying of any muckraking documentary of its kind. The Act of Killing reminds you that no matter how much denial is embedded in a nation’s collective culture, imagination somehow manages to step in as the mind’s own truth squad, the crafty, elusive enemy of anybody’s Thought Police – even our own.

July 10th, 2013 — movie reviews

IMMEDIATE REACTION: What does it mean that while only 26 percent of critics on Rotten Tomatoes’ scale approved of this movie, 68 percent of audiences have so far liked what they saw? Probably nothing. Maybe everything.

It’s way too long – as are so many big-studio blockbusters intent on showing every single dollar spent on screen. It’s at times a tad too pleased with itself, especially in the way it blatantly samples from so many other (better) movies from Little Big Man to The General (lots and lots from The General, in fact, given all those intersecting locomotives) to the collected works of Sergio Leone, Steven Spielberg and even its own director Gore Verbinski. And while it’s far more respectful towards indigenous Americans than you might believe, you still wonder why they all…well, I wouldn’t want to give too much away even if you have no intention whatsoever of seeing The Lone Ranger. And a lot of you don’t, I’m sure, based on its overwhelmingly negative reviews and its underwhelming box-office results thus far.

That bad odor followed me into a bargain matinee of Lone Ranger this week. I couldn’t help it, being of a certain age wherein I cut my teeth on the 1950s Clayton Moore-Jay Silverheels TV series, devoured the legend’s crudely captivating mid-1960s animated TV version and was as recently as a year ago pulling people’s coats about Brett Matthews and Sergio Cariello’s controversial graphic (in every sense of the word) novel which steeped the creaky old mythos in oily western noir. I had to see for myself how bad the movie was and as I watched, I kept waiting for it to start getting as irredeemably awful as everybody warned me it would. It never happened.

In fact, for all of its problems, The Lone Ranger turns out to be a buoyant, insouciantly subversive ragbag epic. As only a few others besides me have noted, even the aforementioned samples from other movies contribute to Lone Ranger’s fun-house distortions of both frontier mythology and popular culture. Yes, it conspicuously takes on the trappings of a gimmicky action blockbuster with a campy Johnny Depp star turn jury-rigged to draw in those who unconditionally loved the last couple of gimmicky action blockbusters with a campy Johnny Depp star turn. But the movie subjects its own motives and methods to constant scrutiny and, in hit-and-miss fashion, weaves this self-awareness into the narrative with goofball nonchalance. It’s every bit the arch, intricately designed feature-length cartoon that the Verbinski-Depp collaboration, Ringo (2011) was, only with more flesh, blood and gore, so to speak. If this version had come out back in 1981, instead of that misbegotten, deservedly forgotten The Legend of the Lone Ranger, it might have been seen as a genre-transforming breakthrough. Now, it’s just a big fat Hollywood summer movie that seemed destined for cautionary-tale status even before it opened.

I wonder why. Just about every summer preview I’d seen this past spring seemed to be spraying Lone Ranger with bad juju. And, as always, the pundits were more concerned with the packaging than with whatever was inside the box. Why, they wondered, dredge up an eighty-something-year-old radio serial that no one under 50 (maybe, more like 55) knows or cares about? The fact that Disney brought back the “team” that gave a grateful world the Pirates of the Caribbean trilogy – which, to this viewer, was at least a movie-and-a-half more than the world needed – seemed to some more like a cynical money-grubbing gesture than a calculated gamble; as if the Giant Mouse was desperately reaching back to “those thrilling days of yesteryear” for its theme parks’ Next Big Thing (though, having seen the movie, I’m damned if I can figure out what thrill ride the company’s going to get out of this one.)

There was also an undercurrent of Depp Fatigue in these advance warnings. In this age of gnat-wing attention spans, the air was buzzing with whispers that Johnny Depp’s high-concept dress-ups were getting thin and (more to the point) less lucrative. Last year’s Dark Shadows applied a coup de grace to the idea of Depp’s outrageousness carrying a movie along. His Barnaby Collins was a blissfully, sometimes poignantly realized reboot. But you kept waiting in vain for the rest of the movie to get better – or get moving. So one imagines the long knives were unsheathed for this Depp turn, especially since he had the cheek to assume the role of Tonto, the title character’s Native American companion. Geez, why not the Lone Ranger? After all, he’s…you know…and you’re…like…and Tonto…He’s…Oh jeez, this is SO awkward….

I’m not going to spend too much time and space here unpacking this issue in all its historical and cultural permutations – and don’t you start with me either. But in the first place, why in the name of John Reid WOULD Depp choose to play the Lone Ranger? Even in the graphic novel, Reid is a decent, dashing fellow who, despite his patrician polish and random knowledge of small firearms, science and anatomy, is the biggest cube in the icebox. Arnie Hammer’s been taking knocks for being a bland, toothy cipher. But that’s what the Masked Man essentially is – and also what Verbinski’s movie chooses to emphasize. Hammer’s just fine in the role; though he does at times betray a level of embarrassment with the hissy fits the movie requires him to toss, especially at Depp’s Tonto, whose reinvention here as both sham and shaman, as trickster and bumbler, as sleazy sidekick and alpha dog, should be lauded rather than castigated. It’s certainly an improvement over the kind of routine abuse Bill Cosby once cited in the second all-time best Lone Ranger shtick by a stand-up comic. (This, of course, is the first.)

And sure, it would have been wonderful for Disney and company to seek out a Native American actor who could bring to this Tonto the kind of comedic timing, deadpan agility and glam-rock swagger that made Depp a star. But we don’t live in that world now. (We should, but we never did and likely won’t in the foreseeable future because trees are smarter, braver and more imaginative than most of the bean counters running the movie industry these days.) As he did with Barnaby Collins and, to a lesser extent, with Willy Wonka, Depp inhabits not just a pop-culture figment of somebody else’s imagination, but our own tangled presumptions about that character to the point where he can upend, shatter and remake those presumptions to his own eccentric specifications. Put another way, it’s hard to think of Depp’s Tonto as red or white (not even with that threadbare makeup cracking and peeling before our eyes.) He’s the stone-faced imp in our collective memory bank, rewiring a hallowed, if anachronistic pop myth so emphatically that even that Kemosabe cube has to rethink his heretofore tidy value system. Also, how can anyone say this Lone Ranger maintains the hierarchical status quo when just about every one of its pale male characters, especially its eponymous hero-savant, comes across as some variant of a “stupid white man”?

This won’t mitigate the carping and it shouldn’t. Just like it shouldn’t have taken 145 minutes to make an entertaining western adventure-spoof. (Blazing Saddles clocks in at 93 minutes; even The Mask of Zorro managed to maintain a brisk, eye-filling pace at 136 minutes, complete with set pieces.) Half the plot strands, even the slingshot-wielding kid who is maybe the Green Hornet’s grandfather, could have been dispensed with. But more not less is, as noted, the profile Hollywood insists upon for action movies. Verbinski’s movie can’t help but resemble a mammoth popcorn spectacle given the global market demands. The real fatigue Lone Ranger represents isn’t with Johnny Depp or even with westerns, though this movie’s perceived failure may have further pushed back the genre’s dim prospects for resuscitation. It’s with the hidebound hot-air chatter over summer tent-poles and trillion-dollar spectacles. If the two guys most responsible for initiating this era of movies now foresee its demise, then the timing for Lone Ranger Redux is even worse. This version should have been made at least thirty years sooner. It could be another twenty years before we can say for sure whether it’s bad or good.

June 16th, 2013 — movie reviews

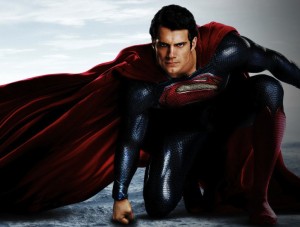

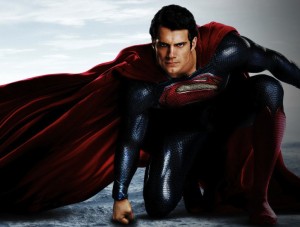

This really shouldn’t have surprised anybody. I’ll go out on a very slender limb and predict that the 71 percent drop for Man of Steel will be even more precipitous over the next few weekends. Summer blockbusters eat each other like the savage carnivores they are and it’s more than probable that by Bastille Day (or, maybe, the Fourth), Clark Kent will join Tony Stark and Mister Spock at the rickety refuse-truck stop on the outskirts of Hype City wondering where the buzz went. The latter two shouldn’t worry too much about coming back. But Superman? He’s in a vulnerable spot. The last time they tried to retrofit him into a new movie franchise, they did it with a movie with an impressive cast, a generally favorable critical consensus (though hardly an overpowering one) and the requisite big-bang set pieces. But for whatever reason, Superman Returns (2006) collected a indecipherable odor that kept it from re-igniting the franchise. In retrospect, Hollywoodland, the neo-noir biopic probing the mysterious death of George Reeves, was the Superman movie that more people talked about that same year. Maybe because it had a better lead actor? You be the judge. I think it may have had something to do with where the world now places its collective memory of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s 75-year-old creation…and whether it believes it can now do without the myth of Krypton’s Last Son.

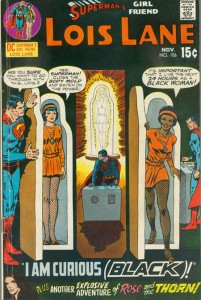

Some of this tangled feeling poked through many of the reviews for Man of Steel (a less impressive consensus this time around, but deceptively so) which moped about Zach Snyder’s reboot having few of the “fun” trappings of Superman’s earlier TV and movie incarnations. These pundits lamented what they saw as the heavy hand of producer Christopher Nolan imposing upon their Superman (whoever that may be) the kind of murky shadows and psychological depth that informed his Dark Knight trilogy’s re-framing of Batman. I found most of these complaints inane and ill-informed. Anybody who grew up reading DC comics at any point in the last 50 or even 60 years knows that there is not now and never has been a life story of Superman that wasn’t subject to revision or tweaking short of making him a refugee from somewhere other than Krypton who landed somewhere other than Kansas.. (Remember all those “what-if” issues of the late 1950s and early 1960s? “What If Lex Luthor Was Superman’s Friend?”, “What If Superman’s Real Parents Came to Earth With Him?” and my all-time favorite, “What If Lois Lane Were Black?” You can look that one up yourself.) For what it’s worth, I always preferred the animated versions of Superman above those with Reeves and even Reeve. Look here and here….and, what the hell, even here.

Ah, yes, that reminds me…Remember the first “teaser” trailers they were showing for Man of Steel, the ones that started running sometime during last summer’s political conventions? They were a gauzy montage of images; a butterfly on a swing, some farmland shrouded in morning fog, a fishing boat with grimy bearded men, a little boy playing with his dog amidst backyard clotheslines with some big red towel or blanket trailing behind him…

At the time, I thought: “Smallville Mon Amour”? I’d be up for that. I figured if Nolan, Snyder and screenwriter David S. Goyer were REALLY serious about dialing everything down to zero and rebuilding the myth from there, they could do a lot worse than take things sideways and make it a more intimate and, thus, more daring species of superhero movie. Sure, you would have bewildered more mass circulation critics, spooked the global distributors and angered the carny rabble. You might even risk flopping worse than, say, Breakfast of Champions or Gigli. Good or bad, you wouldn’t have left anyone indifferent. And what’s more: People would have been talking about your movie beyond opening weekend and (maybe) kept the buzz going all summer long.

As it is, Snyder’s reboot manages to broaden the myth’s expressive possibilities while fulfilling the corporate mandate of blowing things up, literally and figuratively speaking. (More on this later.) Up till now, the romance of being Faster Than…, More Powerful Than…, Able to Leap…, etc. emitted such a powerful hold on our imaginations, at whatever age, that it rarely , if ever, occurred to us to ask what should have been the myth’s most pressing question: How do you adjust to life among other humans if you’re so drastically, even cosmically different from everybody else? A lot of us ran to comic books looking for heroes who were empowered, rather than diminished by being different. What’s best about Man of Steel is its willingness to drink deep from that dilemma. I loved the whole subplot about Clark (and, later, the other Krypton survivors) reeling from the sensory overload caused by being able to see through and hear everything around them. It’s the last thing the lazier savants want to hear: that being super is just another way of being seriously fucked.

There was one moment that chilled me more than anything else in Man of Steel or any other superhero movie in recent memory. It came when Kevin Costner, in his most striking big-screen performance in decades as Jonathan Kent, is reminding his adopted son to resist disclosing his powers, even if they were needed to save his schoolmates from drowning in a waterlogged school bus. “Should I have let them die?” Clark asks. A pause from Pa seems to last forever before he finally mutters, “Maybe.” There’s a web of weary, conflicted emotion enveloping that reply and if the rest of Man of Steel managed to modulate its gaudier impulses in the same manner as Clark struggled to rein in his hearing, it might have been something major, instead of…just big…

…and loud…and messy…I mean I hate being predictable, but count me among the wet blankets who left the theaters grousing about the ringing in their ears and metal shavings in their mouths from all the concussive property damage, the bloodless (and thus, ultimately, numbing) carnage and the multiple rounds of false climaxes that are supposed to let everybody know how much Warner Bros. has spent to keep you distracted. (At least that last Dark Knight movie tried to be clever with its post-traumatic red herrings.) I think I also agree with this writer that there was something especially unnerving about the last of its climaxes — and not in a good or even terribly imaginative way; while I can’t believe I’m still not trying to spoil anything at this point, that climax also looked as if the movie makers were trying to extricate themselves (literally) from a corner & copped out with the least fuss possible.

To sum up: Rather than open new ways to expand or interrogate the Superman myth, this movie turns him into just another action hero who, though he may indeed be hotter than any other (at this point, the only thing people keep talking about after the show’s over is Henry Cavill’s off-the-charts eye-candy quotient) doesn’t exactly make you curious to see where he goes next. And maybe that’s the movie’s biggest problem. But it may also be a problem with our first true superhero, the template upon which all others have been fashioned. The novelty of seeing a man fly faster than sound has worn off, though we’ll never get tired of seeing him surprise others with his feats of strength. (Those vignettes of Clark wandering from one grimy outpost to another, leaving shock and awe in his wake, make up what genuine charm the movie carries.) However Man of Steel ultimately fares in the marketplace, I don’t think they’ll leave the story hanging this time. But rather than whatever the movie’s detractors claim to miss in wit and charm, I’d settle for the simple pleasures of the unexpected next time around.

For instance — and this is in no way a knock on Amy Adams, to whom I remain avidly (avidly) devoted — but, I mean, what about…I mean…why not:

As I said, a sense of wonder….

May 24th, 2013 — movie reviews

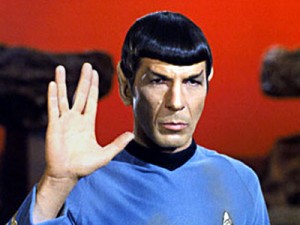

IMMEDIATE REACTION: I had a good time. I expected to. I needed more.

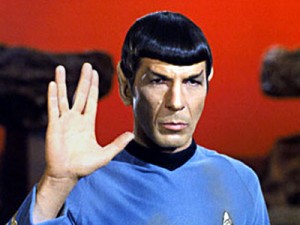

By now, unless you’re sticking your fingers in your ears and going “La-la-la-la” whenever somebody brings the matter up, you’ve probably heard that Star Trek: Into Darkness is supposed to be a riff on 1982’s The Wrath of Khan. Either I’m on the wrong meds or more senile than I imagine, but wasn’t its predecessor supposed to be a rejiggered version of Khan? And if so, is this how it’s going to be from now on, all these new actors in old roles and “classic” uniforms replaying variations on the same story (e.g. evil madman seeks apocalyptic revenge for real and/or imagined crimes)?

If so, then I guess nobody wants to make Star Trek movies any more. Because, let’s face it: Into Darkness isn’t a Trek movie. It’s got all the characters from Trek and the actors who play them are all very good; in one, maybe two cases, even better than their predecessors. But it’s more a movie about Trek than it is a Trek movie. It roots around the attic, appropriating old tropes and familiar names to make the devotees nod in recognition. But what I liked most about J.J. Abrams’s 2009 reboot was its impudent intent to make everything new while remaining attentive to the basic enthusiasm for human possibility that made Gene Roddenberry’s franchise linger for so long in the collective unconscious. (From one dedicated, mildly crazed TV show-runner to another…) Abrams’s follow-up, by contrast, seems content to use Kirk, Spock, Scotty and the rest as action figures that serve the corporate model for summer thrillers; most especially, the Great American Multiplex’s persistant yearning for revenge fantasies along with the attendant surges of explosions, kick-boxing, mass carnage and the obligatory, egregious deaths of beloved father figures. (Be warned: I’m going to respect the “NO SPOILERS” mandate only so much. If you care that much about what happens in this movie, you’ve had plenty of time to see for yourselves.)

True, I wasn’t bored. Which surprises me since there was so little about In Darkness that was new, either in the plot points germane to the Trek mythos or in the usual heavy machinery assembled for standard-issue popcorn phantasmagoria. In fact, I bet the hard-core Trekkers (sic) had themselves a fine time pointing out all the scenes, set pieces and dialogue that had some connection with any and all of the varied Star Trek TV shows and movies. I bet if they tried really hard — and, trust me, so many of them don’t need to try – the SF-movie savants could point out references to other big-ticket movies in their favorite genre. Independence Day cornered the market on such shamelessness, only no one to this day considers it shameless. (It’s a classic, doncha know?) Whatever you call it, this sampling would be barely tolerable if it weren’t offset by the pleasure you get from watching the cast settle into their retrofitted characters. Chris Pine’s Kirk, though properly brash and impulsive, doesn’t yet have the William Shatner strut, though he seems to be quietly assembling his own brand of hauteur to carry into future episodes. Zachary Quinto’s Spock here shows more of the character’s original diffidence; of all the new actors, he’s the most thoroughly comfortable in his (tinted) skin. I still do not buy the office romance between Spock and Zoe Saldana’s Uhura for a nanosecond, but I am loving how she’s taking advantage of Trek 2.0’s greater breadth and depth of her character’s conception. I wish there were much more of John Cho’s rigorously circumspect Sulu, Anton Yelchin’s super callow Chekov and Karl Urban’s somewhat constrained Bones McCoy. I can’t yet tell whether Abrams and his team aren’t quite into the idea of McCoy, which would be a fatal mistake, or whether Urban doesn’t yet have a handle on him. The writers do seem very fond of the idea of Scotty rendered by Simon Pegg as a puckish grump with overcompensation issues. The revision plays to Pegg’s strengths and I’m guessing this series has bigger plans for him than they do for Urban – which would, again, be a big mistake since Trek’s classic verities are rooted in the tug-of-war between the hyper-passionate ship’s doctor and the coolly rational First Officer.

But I’m no longer sure Abrams really cares about the foundations of the old Star Trek as he does in critiquing, if not subverting Roddenberry’s vision. Let me put it another way: Why bother doing the Khan story, not once, but twice? Is it just to show how you can build a better Enterprise? As much as we love these characters in action no matter who’s playing them, it wasn’t just who they were or what they did, but what they represented to us back in 1966: Hope for the future. We’ve not only made it further out in space, but we seem to have managed to make ourselves better, smarter, more tolerant people. We figured out how to live together so well that we seem to be able to get along with people from other planets without being freaked out by the shape of their ears. Now what? That’s what we came for every week. What do we do with this wider perception of our own humanity as we head out yonder? Just as important, what DON’T we do? What is it about this expanded knowledge that keeps us from acting as stupid as some of the beings we encountered on this five-year mission, human or extraterrestrial?

These are the kinds of questions we counted on science fiction to engage, if not necessarily answer. And while we dug watching Kirk and the crew in all those cool martial-arts matches with Klingons and Romulans, the action sequences were access points for the question we knew Star Trek had to ask at some point every week: What does it mean to be human? Into Darkness is into the action sequences, but they seem placed there to sustain our thirst for retribution, which the movies seem to have been exploiting ever since (I’m going to say) 9/11. We no longer seem interested in seeking new life and new civilizations, but in kicking ass and taking names of those bullies who slaughter innocents and blow up our buildings. This yearning for the big win over terror may be who we are. But is it who we want to be? If Abrams and his co-writers are serious about this five-year mission the Enterprise is about to begin, maybe they’ll allow us to find out. But I don’t hold a lot of hope about this. Maybe that’s who I am.

April 16th, 2013 — movie reviews

If you retold Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by moving it several hundred miles upriver, replacing Huck with an older, craftier version of his friend Tom Sawyer and making Jim a younger, more articulate family man, you might well have the true-life, mid-20th-century’s Greatest Story Ever Told: How Branch Rickey and Jackie Robinson engaged on a perilous two-man odyssey to force racial integration down major-league baseball’s throat and make America like it. The difference being that Huck, in refusing to turn Jim over to slave hunters, only thought he was going to hell. Jackie Robinson, throughout that trailblazing 1947 season of triumph and torment (mostly the latter), came as close to an earthbound purgatory as any mortal should have endured.

It’s a story that, much like Huck’s, never loses its power to simultaneously unsettle and inspire. And as with Twain’s masterpiece, no feature film could adequately do it justice, though at least one, The Jackie Robinson Story (1950), made a crude, earnest attempt with the genuine article sportingly, if woodenly, starring as himself. (It’s still interesting to see as a curio of its time and for watching two of our greatest actresses, Ruby Dee and Louise Beavers, on-screen even if they’re only playing silhouettes of Robinson’s real-life wife and mother respectively.)

42, the freshest rendition of the Jackie Robinson parable, is shinier and more authentic than its predecessor – which doesn’t mean it’s any less earnest or doggedly elemental in its execution. I would have no trouble whatsoever exposing a young girl or boy to Brian Helgeland’s digitally enhanced diorama. (It should probably come with one of those labels Milton Bradley used to put on its board-game boxes saying, “Ages 7-14.”) As Robinson, Chadwick Boseman emits the same smoldering intensity as the genuine article while suggesting, at times, some of the prickly-heat feistiness the major leagues would see once he no longer had to turn the other cheek. His scenes with Nicole Beharie as Rachel Robinson have a genuine ardor and unassuming sweetness rare in any movie with an African-American romantic couple. I’d be tempted to say it was a breakthrough for black movies if I thought the movie was all about them. And it isn’t.

For what the story of Jackie Robinson’s trial-by-fire has by now become (in ways that Huckleberry Finn never could) is an occasion for America in general and white people in particular to congratulate themselves on their capacity for change. Boseman’s Robinson may have more dimensions than the version Robinson himself enacted sixty-something years ago. But he is still less a fully fleshed character than a stoic presence, sustaining unspeakable punishment for his country’s sins. This doesn’t in any way mitigate his heroism or importance. But much as America’s astronauts, however fearless, were basically instruments of their country’s scientific and political will, Robinson was the instrument of one man’s far-sighted vision – and determination to overcome his own shame for his beloved game’s racial myopia .

We’re talking, of course, about Branch Rickey, 42’s true protagonist, the man who pulled the strings for this “great experiment” and made sure none of them were clipped. There sometimes seemed almost as many leading men in Hollywood yearning to play Rickey as there were wanting to play Chet Baker, though a far more motley group in the latter queue. Harrison Ford makes the most of his rare opportunity to go big, broad and hard. I hear some gripes about Ford going too far over the top – which discloses nothing so much as the complainers’ ignorance of baseball history. Outside of, say, Bill Veeck, Larry McPhail and George Steinbrenner, Branch Rickey is the only baseball executive whose larger-than-life presence is worthy of a movie. If anything, Ford seems at times a little too conscious of Rickey’s many facets (which, in Red Smith’s immortal turn-of-phrase, were all turned on). But it’s such an endearing performance throughout that you even enjoy Ford’s straining to get it just right.

The rest of the actors pretty much carry out their roles in this parable as expected, though history would have been better served by showing that Philadelphia Phillies manager Ben Chapman (the admirable, under-appreciated Alan Tudyk) wasn’t the only one in that team’s dugout ragging Robinson so viciously. (The late Richie Ashburn was one of the few players on that team in that era who owned up to such taunting and expressed his deep regret for it.) Poor old Dixie Walker (Ryan Merriman) must once again be properly humiliated for trying to whip up his white Dodger teammates in opposition to Robinson – though in later years, he pleaded for forgiveness from the press and public. As for Christopher Meloni’s Leo Durocher, he’s such a magnetically funny and vividly rendered character in his precious few moments onscreen that when he’s compelled to leave the team (and the movie), you wish you could follow him out the locker room door to watch what happens to him – and, of course, Laraine Day (Jud Tylor). There’s another movie waiting to be made, and if they’re smart, they’ll let Meloni continue in the role.

As for 42, it may not cut as deep as most of us would like. But it may say something about my own diminished expectations of Hollywood that I doubt we’re going to get a better movie version of this story for some time to come. Dioramas and comic books are what sell in the multiplexes these days and as long as the outlines and colors are reasonably aligned and the proper emotions are aroused, then I’m willing to settle for harmlessness as a virtue; just as long as nobody tries to sell 42 as genuine progress. Popular culture as a whole still can’t accommodate the complexity of a real-life Jackie Robinson who in the years since his arduous rookie season was fueled by unceasing rage and uncompromising passion for justice. Indeed, Hollywood movies in general still can’t adequately deal with emotional complexity of any kind — and may have stopped trying.

February 25th, 2013 — movie reviews

Here are some things I didn’t have time or space to squeeze into this CNN thingee. (I had to sleep sometime after all):

1.) Watching some of “Jimmy Kimmel Live” last night & noting how the post-Oscar cast was more enjoyable, and a tad funnier, than what it followed (& that includes Your Local News), it occurred to me that all awards shows, except maybe the Tonys, will have to become desk-and-couch affairs if they expect to survive as annual broadcasts. I know historians now regard David Letterman’s turn-at-bat as a cataclysmic whiff. But imagine how he’d have done if he’d been in his comfort zone with Paul pouring the necessary smarm over everything. It may be another ten years or so before that happens, by which time desk-and-couch shows will be as obsolete as analog phones.

2.) If this year’s producers were so damned anxious to have a Broadway feel to this thing, why didn’t they just call Neil Patrick Harris to the captain’s chair & let him go nuts? He & Billy Crystal may be the only two people alive who know how to go meta with this glitz while still respecting it as glitz. Good luck boosting next year’s ratings.

3.) You know what was even more enjoyable than Kimmel or the Oscars? Cruising Facebook & Twitter for immediate reactions to last night’s awards. Maybe the future will really involve people showing up on red carpets in fancy clothes before heading into chat rooms to tap out the individual impressions through their FB pages or shoot their own video. The Academy will take care of the rest by mailing out the statuettes in advance. In Anne Hathaway’s case, at least, I though they did, anyway.

4.) I wasn’t surprised that both Lincoln and Zero Dark Thirty got relatively shut out, even though I thought right up to the end that the hacks respected Tony Kushner’s ability to effectively dramatize difficult material. Instead, the hacks got theirs by raising a middle finger to those who slapped Quentin Tarantino upside his head for turning slavery into, if you will, pulp fiction. (As I told CNN, wait twenty years…)

5.) Paraphrasing Oliver Stone, there’s the way America is & the way we ought to be. Argo, as I wrote in my CNN piece, was the way Hollywood & America prefer imagining themselves while Lincoln, The Master and Zero Dark Thirty reflected, in different ways, what they, and we, really are. That the Academy voters let controversy (or at least its prospect) get in the way of acknowledging those movies suggests that even the opposite edges of the continent are as polarized & tied-up-in-knots as the rest of America.

6.) People ooh-ed and aah-ed over Michelle Obama’s hook-up with Jack “King” Nicholson. (She has that effect on people, especially after she did the hippy-hippy-shake with Jimmy Fallon last week.) What I was hoping for, ever since last summer, was an excuse to put Clint Eastwood on stage last night and have Michelle’s husband show up in a chair off to Eastwood’s left. “Did you have something to tell me?” the president would have asked in, of course, the nicest possible way. A braver world than this would have allowed it to happen. As last night awards made clearer than ever, we do not live in a brave world, except when we’re tossing snark through our keyboards. In the meantime, I love you, Amy Adams & wish you better luck next time.

February 17th, 2013 — movie reviews

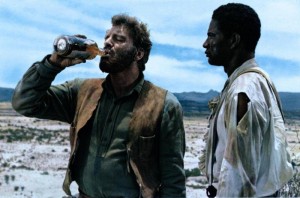

Not to press the point too hard, but for those who’ve seen Django Unchained and still wonder, or even care, about its relative closeness to historical authenticity, there is this much about which they can be reasonably assured: Most white folks were as serious as cancer about not letting black people ride horses. Didn’t matter if they were free or not. After all, if slaves see other colored people on horses, they may start getting…ideas. Livestock wasn’t supposed to have ideas. And livestock wasn’t supposed to be riding on top of other livestock either. Silliest damned thing a southern planter with any wits about him could bear to imagine. Like having a goddam goat riding a pig! Now don’t that sound wrong as hell?

Livestock: Let’s be emphatic, shall we, as we “observe” yet another Black History Month. It didn’t matter way back when whether the black people looked like Kerry Washington or Oprah Winfrey, like Jamie Foxx or LeBron James, like the incumbent president of the United States or his stunning wife or their two lovely daughters. If they were in the American South before 1863, they were all livestock and not even papers claiming their freedom could ensure that they wouldn’t be arbitrarily tossed into a corral, roped, branded, chained and treated only a feather or two better than the chickens.

If you’re livestock and leave the corral, they’ll put you in a cage. And you don’t ride anywhere unless the cage somehow rides with you – or you walk behind any white man on a horse, even if that white man is stupider than you, or his horse.

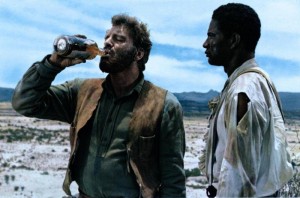

A movie, I say with mild embarrassment, first placed this gross disparity before my callow sight line. The Scalphunters, released in 1968, was the third feature film directed by Sydney Pollack, a name I’d recognized from some quirky television work as well as a feature he’d directed three years before, The Slender Thread with Sidney Poitier and Telly Savalas as psychiatric caseworkers trying to save Anne Bancroft from suicide. This particular movie was a western with another intriguing interracial star pairing: Burt Lancaster as a fur trapper and Ossie Davis as an educated fugitive slave he’s forced to acquire as compensation for the pelts he loses to a group of cagey, sybaritic Kiowa.

The trapper, Joe Bass, rides off after the tribe while making the slave, Joseph Lee, stumble along the trail after him, mostly on foot. Joe is, after all, a man of his times and those times dictate that he should eventually sell off Joseph Lee to whomever offers the best price. To his credit. Joe does let Joseph Lee ride the horse just long enough for the latter to attempt a getaway. One whistle from Joe and the horse tosses the disconcerted slave from the saddle. (Bass: “You seem to have an uncommon prejudice against service to the white-skinned race.” Joseph Lee: “I don’t mean to be narrow in my attitude.”)

When they catch up with the Kiowa, they’ve pretty much emptied Joe’s whiskey supply. “You ever fight twelve drunk Indians?” Joe Bass asks Joseph Lee. “No, sir,” the latter replies, “but I’d like to see it done.” But before that show can start, it’s pre-empted by marauders roaring and slaughtering and relieving the tribesmen of their scalps and of Joe’s purloined furs. Joe Bass considers the genus of outlaw making money off dead Indians’ hair to be “the wickedest, crookedest trade to ever turn a dollar.” Joseph Lee, who intimately knows an even more wicked way of making money, can only stare back in what seems to be incredulity. We’re not quite sure how long before the Civil War this tale is set. (I’ve read some accounts that place it in 1860.) But we know by this point that Joseph Lee’s smart enough to keep his counsel here.

Still, for the first part of the movie, you wonder how Ossie Davis maintains his own composure. At the time this movie was made, Davis had achieved international esteem as both an actor and a writer with a successful play, Purlie Victorious, in his resume. He’d also established considerable credibility as an activist and was the principal eulogist at Malcolm X’s funeral in 1965. One was used to seeing Davis by the late 1960s, in varied roles on-screen – save for a leading one, despite his magnetism and warmth. Despite his reputation, Davis was billed beneath Lancaster, Shelly Winters and Telly Savalas. So however shrewd the movie’s tactics were, he must have thought a little harder than usual about the idea of playing in an antebellum comedy-western in which the only role available to him would be that of a runaway slave, albeit one who spent most of the movie choking down rage and humiliation with foxy erudition and oneupmanship.

Keep in mind, also, that the year this movie was released (the same week that Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered in Memphis), Davis was in the vanguard of a wave of African American writers publicly chastising William Styron for writing what they believed to be a facile (at best) novel about Nat Turner and his 1831 slave revolt. At the time, many of these writers, including Davis, were asked why they hadn’t written a novel or play about slavery. Davis, I seem to recall, at least acknowledged that he hadn’t written his own work challenging Styron’s vision — though he would in 1969 appear in a movie, Slaves, memorable, if at all, for being Dionne Warwick’s first — and last — starring role in a motion picture.

Davis didn’t have to perform in that silly, overwrought movie or write his own play or book to contribute to the culture’s evolving view of American slavery. If he wanted to make his own response to Styron’s Nat Turner, either as correction or counter-text, his Joseph Lee was more than enough. Within minutes of his appearance on-screen, Davis lets you see his character’s cultivation, grace and instinctive ability to tame the savage white man. You also see his wit, dignity and, as noted, his slyness. The joke of a black slave being smarter than the he-man white hero made for a nice gimmick in the years when multi-racial casting in westerns was still a relative rarity; westerns themselves now being relative rarities. Indeed, the white male characters in Scalphunters, including the marauders’ bonehead ringleader Jim Howie (Savalas) are nowhere near as smart as Joseph Lee, the crafty Kiowa chief Two Crows (Armando Silvestre) and Howie’s sassy significant-other Kate (Winters, sultry and kittenish in what was likely her last sex-bomb role).

But there’s a point in the movie – a sharp, glistening point – when Davis emerges as much more than a clever plot device. It comes as Joseph Lee, having accidentally fallen into the marauders’ camp and then finagling his way into accompanying them to the Mexican border, goes back to where Joe Bass has been a one-man guerilla force in pursuit of his pelts. He greets Bass’ hostility with both a supplicating smile and a bottle of whiskey from Jim Howie’s private stock. “I thought,” Joseph Lee grins, “you could maybe use a drink about now.” Bass takes the bottle with contempt for the way Lee accommodated himself with the gang, not even bothering to acknowledge Lee’s facility for survival – or his urgent need to go to a country where there is no slavery All Joe can say of Joseph’s resourcefulness is: “Throw you in the pig pen, you’d come out vice-president of the hogs,” he spits. (See? Livestock…)

When Joseph then asks if he could have a sip, Bass snarls back, “If I was to give you a drink of this whiskey, it’d be like pourin’ it out in the sand. This is a man’s drink. And you aint no man. You aint no part of a man. You’re a mealy-mouthed shuffle-butt of a slave and you picked yourself a master. So don’t go askin’ to take a drink with a man.”

At that dreadful moment, all of Joseph Lee’s canny defense mechanisms vanish, exposing a shaken, wounded, and somewhat volatile visage. It’s as if Bass’s cruel words yanked away the slave’s shirt to expose the scars of several dozen lashings, not all of them physical. Davis makes his face register a host of warring emotions before it changes into something harder and tougher than what the audience, up to that point, had been accustomed to seeing. As with the greatest actors, he does this before you’re even aware that it’s happened. And Davis, make no mistake, was one of our greatest actors.

Joseph, recovering his voice, lowers it. He tells Joe Bass just how small and stupid he really is, without using either of those words. And then he says, “You know how long you’d last as a colored man? About one minute.” That single line does the work of several-hundred words of steamy, hopped-up rhetoric by Leonardo DiCaprio or Christoph Waltz in Django about the ingrained distortions of humanity that remain the principal legacy of America’s Original Sin. Before long, the two of them will end up slugging each other in a mud hole, only to ultimately be left behind yet again, with one horse, no furs and no passage to freedom. The difference is that, this time, they both wear brackish, grayish coatings of caked, wet dirt. With no color distinctions between them, they’re just another pair of wayward desert flotsam.

Back in 1968, there were some who likely believed such an ending rubbed the audience’s faces in social consciousness, so to speak. Yet I’m willing to bet if any contemporary Hollywood movie tried the same approach, some would say they were being too subtle. A movie like The Scalphunters could take its time, keep things light, make its points by stealth. Now some would wonder if it’s being too frivolous. As the many Joseph Lees in history who made up their beings as they went along would tell you, there are as many ways to be tough and resilient as they are to telling stories. This crafty little movie, which somehow got lost in an emergent wave of boundary-busting Hollywood films, deserves our attention for making that deceptively simple point.

January 29th, 2013 — movie reviews

IMMEDIATE REACTION: I know what you’re thinking. At this late date, who am I to put twigs on a fire that’s dying out anyway? After all, nobody cares a fig what I think about torture. I’m not sure I care either. It’s like what Randy Newman said about the Spanish Inquisition that “put people in a terrible position/I don’t even like to think about it/Well…sometimes I like to think about it….”

1.) I’m just going to throw this out: The Hurt Locker is a better movie, though there are stretches of righteous filmmaking in this one; not surprisingly, they all come as the movie approaches the precipice of shattering violence. (The build-ups to both bombings, especially the Christmas morning attack; the whole climax, etc.) It’s not entirely Kathryn Bigelow’s fault any more than it’s Jessica Chastain’s fault that she’s stuck playing not a character so much as a state-of-mind. (More on this in a minute.) To me, doing this story so soon is like someone making JFK in 1966 — and something tells me if Oliver Stone were able to do so back then, he would have. Even before the movie was released, I was wondering what the rush was to get this story on-screen, irrespective of the controversy over torture. (More on THAT in a minute, too.) If I chose to practice armchair psychology (& since it’s just us talking, why not), I’d guess that K.B. was drawn to the idea of a brilliant, ballsy young heroine whom no one — no MEN, specifically — takes as seriously as she demands to be taken. (I’d love to see K.B. someday do HER side of James Cameron’s The Abyss, though it wouldn’t necessarily have to be the same story.) I think Zero Dark Thirty is taking a beating mostly because its narrative is still current enough to be mistaken for journalism where if it were made and/or released ten or twenty years from now, the movie would be viewed correctly as historic events filtered through imagination. It may take twenty years for that to happen anyway.

2.) By now, I’ve read & heard just about every attack on Zero for its depiction of torture; that it glorifies or misrepresents torture as being key to getting a lock on Bin Laden’s whereabouts or is shilling some kind of thinking-person’s version of “USA! USA! USA!” triumphalism. (For balance’s sake, I shall include both Greg Mitchell’s measured dissent of the movie in his Nation blog and Glenn Kenny’s elegant and thorough skewering of the movie’s attackers.) As I’ve already said, I think the movie kind of asked for the pummeling it’s getting by throwing all this stuff out there unmediated by time’s passage & the intervening revisions & disclosures that could broaden understanding of the whole War-on-Terror era. But if the leftist pundits out there truly believe that the movie’s audiences are going to watch these waterboarding-and-boxing-in scenes & feel in any way ennobled or roused by the CIA’s savvy, then it sounds to me as though they’re not only underestimating people’s intelligence (to say nothing of their capacity to be grossed-out), they’re sort of buying into the blinkered bullshit about the Power of Movies without any real knowledge, intuitive or otherwise, of what that Power really is. (Getting back to JFK, do you really think that movie changed anybody’s mind about whether or not Oswald acted alone? If anything, that movie bullied people into thinking, “Who cares anymore who killed Kennedy?” — just as, it could be argued, Spike Lee’s Malcolm X swallowed or exhausted whatever public acrimony or controversy remained about its subject, too.)

3.) And as for the triumphalism, I REALLY don’t get where that criticism comes from. You most emphatically do not walk away from Zero Dark Thirty feeling cleansed, cathartic or especially patriotic. If anything, it comes across as an anti-revenge revenge movie, if that makes any sense. From the very beginning when you hear the wailing of the soon-to-be-dead woman in the soon-to-collapse Twin Towers to the very end when you see Chastain’s Maya, isolated on a transport plane she has all to herself, weeping & desolate & not quite sure anymore who she is or where she goes from here, Zero Dark Thirty resounds as nothing so much as a melancholy dirge on America in the ten years between the raids of both 9/11 and 5/1; of what we became or compelled ourselves to become in the wake of a heretofore unimaginable trauma. (This review, from what seem like eons ago, puts it better than I just did. )Maya is the embodiment of that mind-set, a blank space upon which we’re supposed to project our own seething desire for closure or payback. She doesn’t have any past except the one we’re supposed to conjecture. (Did she have some connection with the woman on the phone in that 9/11 prelude? I haven’t read anything that suggests that, though I’m sure it’s out there somewhere.) That Chastain makes this enigma substantial enough to carry this movie is, I suppose, reason enough to give her an Oscar nomination. Still, a blank space is no substitute for a real person & not even that moist coda she delivers is enough to make me believe in her. She likely had less to work with in The Tree of Life & she somehow evoked everything about that mother’s past, present & future. I guess if Zero does anything for her, it’ll make her a convincing starship captain in some Star Trek sequel, assuming she ever wants to go where no method actress has gone before.

4.) So little does Zero troll for patriotic cheers that I think it hurts its own chances for collecting any Oscar whatsoever. Argo. Now THERE’S a movie that makes you stand up and go “USA! USA! USA!” at the end. It’s the principal reason the Academy now regrets not giving Ben Affleck a director’s nod & why it now looks as though his movie’s poised to eat everybody else’s lunch, even Abe’s. Just as Rocky trounced All the President’s Men & Network in 1976 & Crash beat out Brokeback Mountain in 2006, the movie that makes Hollywood feel better about itself will likely clobber the movies that feel too much like Homework. (Remember: I’m forcing myself not to care this year who wins what…)

January 8th, 2013 — movie reviews

NOTE: I’ve also written a piece for CNN.com covering most of the same ground here. If you want to compare or contrast, click here.

IMMEDIATE REACTION: If loving Django Unchained is wrong, then I don’t…well, let’s see. What is it exactly I don’t want to be? That is the question. One of many…

Let’s tip off with a question that may not have an immediate or easy answer: Which movie better empowers black audiences? An historic drama, more or less factually-based, in which white men argue over and eventually move towards ending slavery – if not racism? Or an historic fantasy, rife with vulgarity, anachronism and impropriety, in which a freed black slave lays waste to every white southerner impeding his reunion with his wife — and gets away with it?

I am not asking which is the better movie, Lincoln or Django Unchained. Both have their problems. But it’s possible, despite their flaws, to enjoy them both for what they are, while accepting what they are not. I did not expect Lincoln to be much different from any other Steven Spielberg movie (though, until the ending, it is) and I certainly didn’t expect Django to be anything other than a Quentin Tarantino movie (and it is, only more so, for better and worse.)

For whatever it’s worth, my issues with the movie have more to do with craft than substance. I think Django talks too much, even for a Tarantino movie; and I also think that many of its scenes go on for too long, almost as if the movie’s afraid to let go of whatever effect it thinks it’s making with those people in the dark. It occurs to me, as well, that Tarantino’s been ripping himself off too cavalierly. I watch the set-pieces of wholesale slaughter and think, if I didn’t know any better, I’d swear I was watching Kill Bill Vol. 1 and the Japanese have been turned into southern whites.

Still, I couldn’t help myself. I laughed at Don Johnson and his night-riding stooges throwing hissy fits over whether to keep their masks on. I was almost touched by the slave girl’s impromptu bon mot aimed at Django’s baby-blue fop’s outfit. “You’re free…and you want to dress like that?” I didn’t buy any of it. But I was into it. And part of me hates myself for it. But I’m not sorry I saw it.

All right, then. So what am I asking? Get comfortable. I’m going to digress.

Back in 2006, I reviewed Blood Diamond for Newsday, giving it the two stars I routinely doled out to generic Hollywood mediocrity. I acknowledged the importance of the movie’s theme, which was the exploitation and wholesale murder of black Africans for the sake of the pink diamond trade. But I found myself chafing over the way this movie, along with so many of its kind, depicted its dark-skinned characters “as wholesale cannon fodder, doomed-but-noble ciphers or sneering bloodthirsty sociopaths.” I also lamented how the always-exemplary Djimon Hounsou, cast as a fisherman from Sierra Leone searching for his captured son, was used mainly as a vehicle through which the morally indolent white mercenary played by Leonardo DiCaprio Finds His Humanity (or something like that). At one point, Hounsou’s character even wonders aloud whether his people’s black skin constitutes some sort of curse “and [that] we were better off when the white man ruled.” No one, certainly not DiCaprio’s character, bothers to engage, much less contradict, this query. And, of the movie’s critics, I recall only the Nation’s Stuart Klawans calling the movie on this odious hogwash.

This is how I ended my own review:

“I suppose we should be grateful that there have been so many commercial features in recent years (“Hotel Rwanda,” “The Constant Gardener” among them) that pay attention to Africa’s woes. But even the best of them seem to writhe from hopelessness to despair and back again. Maybe what the continent needs are some empowering pulp myths far beyond the hoary model of Tarzan. A good start would be to cast Hounsou as the lead in a movie about the Black Panther, Marvel Comics’ first superhero-of-color. An African king who’s both a world-class physicist and a supreme martial artist may not be plausible, but he could broaden moviegoers’ sense of what’s possible.” (ITALICS ADDED).

Some readers, at least those who got that far, seemed to have a problem with this notion. One used the word, “infantile” (which over time I’ve accepted as a back-handed compliment). But what is so childish about African American audiences wanting their on-screen counterparts (or surrogates) to be more than merely victims? I believe even white audiences get excited when conventional expectations, especially in race and cultural matters, are upended, if not exactly transcended.

This is the excitement I hear from people after they’d just seen Django Unchained. I doubt whether any of these viewers bought their tickets with the expectation of seeing some historically faithful saga of antebellum life, and neither did I. They were buying a comic book. Many people have a grievance against the very notion of comic books, but I don’t. I understand that comic books as a medium are limited in what they offer their clientele. So are the movies, especially those who cruise the multiplexes for loose coin. Expect a movie or a comic book to explain everything about anything and all you earn is surplus sadness in your life that you don’t really need.

Even with the narrowest expectations about historical veracity, however, things get complicated when the subject matter is American slavery, European Holocaust or any number of similar assaults upon humanity. Hence the reaction to Django, after less than a month of swimming in the mainstream, ranges from sheer exhilaration to outright hostility, with the usual gradations in between.

Much of the resentment seems aimed exclusively towards Tarantino himself; a visceral dislike which I think has a lot to do with Spike Lee’s outright refusal to see the movie, tossing grenades at it all the way. Ishmael Reed, writing in the Wall Street Journal, believes Tarantino shows willful, if not willed ignorance of history, both American and cinematic. He writes: “To compare this movie to a spaghetti western and a blaxploitation film is an insult to both genres. It’s a Tarantino home movie with all the racist licks of his other movies.” Reed aimed this laser shot at the Oscar-nominated actor who plays the treacherous “house slave”: “Samuel L. Jackson…plays himself.”

I doubt Jackson felt the blow. He has, in fact, further provoked the movie’s antagonists by running straight at an interviewer asking about the movie’s prolific use of the “N-word,” refusing to answer the question unless the reporter, who is white, actually says the dread epithet aloud. (He didn’t.)

Though I disagree with Reed’s conclusions, I think everyone who saw Django should read his piece for its flying shrapnel of loose insight and, most important, its disclosure of what has always been a relevant source of disquiet: The debate over whether white artists have the right to tell any part of the black American story – which, as Reed writes, is as old as Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

It is also as recent as 1967 when the white southern novelist William Styron published The Confessions of Nat Turner, a Pulitzer Prize-winning novel told in the first-person voice of the brilliant-but-doomed leader of an 1831 slave rebellion. The outcry from African American novelists was so intense that a collection of essays, William Styron’s Nat Turner: Ten Black Writers Respond was published a year later. When I was a credulous, anxious-to-please teenager, I was so in thrall to the authority exerted by those black writers that for decades afterwards, I refused to even go near Styron’s book.

I still haven’t read it. But I plan to, because I now believe that James Baldwin, a friend of Styron who was one of the few African American authors speaking out on the book’s behalf, had the right take from the beginning: “I will not tell another writer what to write. If you don’t like their alternative, write yours.”

It’s still sound advice – and in the intervening years, black authors have taken it. Indeed, if anyone’s earned the right to rail at Django, it’s Ishmael Reed since, unlike Spike Lee, he’s actually created his own antebellum thriller that’s as funny, provocative and calculatedly anachronistic as Tarantino’s. I can almost hear Reed erupting with outrage over the sheer notion of my comparing Django with his 1976 book, Flight to Canada. But as I insisted to friends and fellow readers at the time (and continue to do so), even with all its musical-comedy interludes, burlesque elements and television cameras, Reed’s shrewd take on the slave-narrative genre had more trenchant, telling and useful things to say about the Peculiar Institution than Alex Haley’s Roots, which was ascending, that same year, to the rare stature of pop-cultural phenomenon. When Haley’s book became a television mini-series, it affected America’s racial attitudes as nothing of its literary kind since…Uncle Tom’s Cabin. No one’s bothered to do anything with cinematic Flight to Canada. Or, for that matter, with Charles Johnson’s Oxherding Tale and Middle Passage, two other antebellum satiric adventures written by an award-winning black author.

In 1987, there was Toni Morrison’s Beloved, which did get adapted for the big screen eleven years later by Jonathan Demme. But even with Oprah Winfrey’s imprimatur as producer and co-star, the movie earned about $26,000,000, roughly half of its $50,000,000 budget. And while all I have is anecdotal evidence, I remember many of my African American relatives and friends who told me they were not going to see Beloved, no matter how good it was or who was in it, because they simply did not want to watch a movie about slavery, or its legacy.

This reluctance to engage with the subject of slavery is duly noted in Jelani Cobb’s ruminative take on Django:

“In my sixteen years of teaching African-American history, one sadly common theme has been the number of black students who shy away from courses dealing with slavery out of shame that slaves never fought back. It seems almost pedantic to point out that slavery was nothing like this. The slaveholding class existed in a state of constant paranoia about slave rebellions, escapes, and a litany of more subtle attempts to undermine the institution. Nearly two hundred thousand black men, most of them former slaves, enlisted in the Union Army in order to accomplish en masse precisely what Django attempts to do alone: risk death in order to free those whom they loved. Tarantino’s attempt to craft a hero who stands apart from the other men—black and white—of his time is not a riff on history, it’s a riff on the mythology we’ve mistaken for history. Were the film aware of that distinction, Django would be far less troubling—but it would also be far less resonant. The alternate history is found not in the story of vengeful ex-slave but in the idea that he could be the only one.”

Cobb’s ambivalence approaches my own point-of-view, even though I still liked the movie better than he did. As with other critics, he laments Django’s lapse into revenge-movie mode. I lament the fact that almost EVERY big-studio film is built for revenge, even romantic comedies. (What, after all, is Skyfall but the mother-of-all-revenge-fantasies with different agendas for vengeance overlapping and colliding into each other like a freeway pile-up?) No matter. If Django Unchained did nothing else but arouse re-examination of “the mythology we’ve mistaken for history,” then all the trouble and fuss it’s caused will have been worth it.