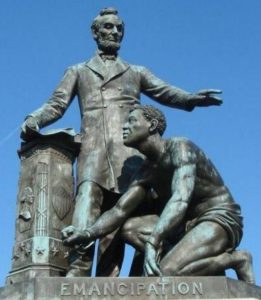

Both my age and my lifelong inclination to study History place me squarely on the side of those who want to leave the Emancipation Statue where it is in DC’s Lincoln Park. I do, however, understand the problem today’s Black Lives Matter generation of activists have with it and why they’d like to see it go away. The sight of a newly freed slave crouched beneath the Great White Father/Emancipator looks so patronizing when framed against the present-day urgency that it likely doesn’t matter to Millennials and Generation-Z African American activists that this particular piece of public art was paid for almost entirely by freed Black slaves and that it was unveiled in 1876, which would be the last year of post-Civil War Reconstruction and the beginning of Jim Crow’s reign of terror in the South and elsewhere. Nor will it matter to them that before that statue (sculpted by a white artist named Thomas Ball) there were precisely no statues in the Nation’s Capital depicting a black person and quite likely a very long time before there would be another.

No, I suppose that there may be from here on a dispute between generations of Black folk in Washington and elsewhere over the optics of this statue. But “optics,” I’m thinking, are the least of it. This isn’t just a dispute over a statue. It revives an ongoing referendum Black Americans have had for at least a couple generations over the legacy of Abraham Lincoln. It’s a dilemma that goes all the way back to the statue’s unveiling, when Frederick Douglass, who spoke at the dedication ceremony, rehashed some of his own mixed feelings towards the 16th president he got to know well enough to be impatient with him when it came to not only Emancipation, but what would, or could, happen afterwards.

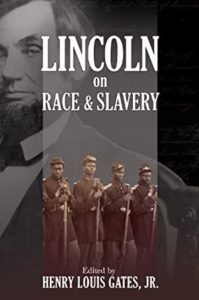

I came of age at the outset of Lincoln revisionism among Black writers and historians such as Lerone Bennett Jr. and Julius Lester during the 1960s. Decades later, I had a chance to openly declare where I landed, more or less, on the Lincoln dilemma when in 2009, the bicentennial year of his birth, American History magazine assigned me to review Lincoln on Race and Slavery (Princeton University Press), in which Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Donald Yacovone gathered together excerpts from speeches, letters, and debates to create a mosaic of Lincoln’s racial politics which, though by no means conclusive or satisfying to anyone, may well be the best we’ll ever get in one volume beyond making the effort to sift through his papers ourselves.

My piece, printed in its full (pre-publication) form below, wont settle anything either. But I love the process of coming-to-grips with things that are as American as a burger stand or a blues joint. Which is why I love the arguments over the Emancipation Statue for their own sake. I hope they never stop arguing about it because, to a considerable extent, it serves Mr. Lincoln right.

This year’s bicentennial celebration of Abraham Lincoln’s birthday finds us in a far different state-of-mind than 100 years ago, when the 16th president’s stature as a secular saint was pretty much taken for granted. Now we have questions. They come from many walks of life, but the civil rights movement that, many believe, finished what Lincoln started, has especially made African Americans, once his most devoted and unequivocal acolytes, turn a more gimlet eye towards the Great Emancipator and his legacy.

Among their questions: If Lincoln really hated slavery, why did it take so long for him to declare emancipation? And is it possible that he didn’t love black people as much as they loved him? After all, he kept insisting that, once slaves were freed, he’d rather have them all shipped back to Africa rather than given the same rights as all American citizens. Or did he?

You can get whiplash sifting for answers to these and related questions through the corpus of Lincoln’s letters, speeches and official documents. So Henry Louis Gates Jr. does the work for you with Lincoln on Race and Slavery, a compilation of excerpts from Lincoln’s writings dating back to his earliest anti-slavery statements as an Illinois legislator in the late 1830’s to his last public address on April 11, 1865, in which he said black Union troops proved they were worthy of enfranchisement as voters. John Wilkes Booth heard those words and decided the president had to die for them – which, with Booth’s help, he did four days later.

Along with the PBS documentary Looking for Lincoln, Lincoln on Race and Slavery represents Gates’ conscientious effort to re-engage, if not altogether reconcile, with Abraham Lincoln as man and legend, hero and conundrum. The film, however, is more travelogue than analysis. Gates, both host and co-producer, lugs Lincoln’s complexities and contradictions into personal encounters with fellow scholars, tour guides, schoolchildren and even some present-day stars-and-bars sympathizers. The image of the nation’s “go-to” black public intellectual making nice with proud sons and daughters of the Confederacy makes for interesting television, but seems symptomatic of the intermittently provocative drift permeating the entire enterprise. Viewers could be forgiven for complaining that the film doesn’t answer any of the above (or related) questions; nor does it resolve issues it raises.

But as Gates makes clear in his far more cogent introductory essay to Lincoln on Race and Slavery, looking for simple or comforting resolution even in the man’s own words (the only rational option at hand) may be a fool’s errand. With a surgeon’s deftness, Gates (with help from editor-writer Donald Yacavone) fashions a simulacrum of a state-of-mind at constant war with its assumptions and ambitions. To read the segments gleaned from the epochal 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debates, you’d think Lincoln spent most of his time reassuring his white audiences that, of course, he didn’t believe blacks were sufficiently human to mix with their kind; at the same time, he kept insisting that the Declaration of Independence’s assertion that “all men are created equal” applied to black men as well. A contemporary reader could at once bemoan such brazen avoidance of consistency while marveling at the rhetorical agility of what Robert Lowell, in an otherwise disapproving sonnet to the Emancipator, deemed “our one genius in politics.”

And yet, the artifacts of that genius become more tangible, more manifest, when they surge from beneath the web of its owner’s calculation, forcing his listeners to confront not only “the better angels of our nature” but the darker forces within. One thinks, particularly, of the moment in his 1858 speech in Edwardsville, Illinois when he dares to ask whites about dehumanizing and subjugating blacks: “Are you quite sure the demon which you have roused will not turn and rend you?” Skeptics of all colors are free to doubt whether Lincoln still belongs to the ages. But when you see how such a question may still be posed in your own life and times, you’re hard-pressed to deny lasting resonance to such fierce and mighty words.