You had to wait till HBO’s Perry Mason ran its course to realize how good it was in the same way you had to wait till the end of a vintage CBS Perry Mason episode to find out who the real murderer was.

It was good and, at times, great. But it was touch and go throughout, world. If you’re binge-watching it now, you might not appreciate how many of us who took each episode in weekly installments were ready to bail on this old/new/new/old iteration of the Lawyer Who Never Loses. The art direction, which remained the true star of the series till the end, kept our heads in the game with its meticulous recreation of Los Angeles in the deepest pit of the Great Depression.

But brothers and sisters, did this ship take its sweet old time to reach port! It seemed intent, at times, on creating its own fog and squalls along the way. One more histrionic revival meeting, one more instance of Perry (Matthew Rhys) physically and emotionally getting his butt kicked, and some of us were ready to abandon ship without bothering to find out what kind of asshole sews open the eyelids of a dead infant as a way of making his parents think he’s still alive.

Which doesn’t sound even remotely like the kind of murder case that would create billable hours for Raymond Burr’s Perry Mason back when he was sweeping the courtroom floors with William Talman’s Hamilton Burger on CBS’s prime-time schedule in the late fifties and early sixties. Granted, those old shows could get pretty weird themselves with their noir-ish SoCal landscapes, berserk red herrings, cobra-like plot shifts and absurdly alliterative episode titles like “The Case of the Woeful Widower,” “The Case of the Bountiful Beauty,” “The Case of the Devious Delinquent” – and that was just the seventh season!

Yet I happily and regularly devour those old CBS episodes as have many of my friends lately for the tasty, caloric comfort food for the soul they always were. Yes, they were formulaic. But as art critic Dave Hickey writes in his wondrous essay, “The Little Church of Perry Mason,” there remains after all these years something at once sublime, gnomish, fortifying and finely wrought about the series; Hickey especially appreciates how, after a murderer’s confession was successfully yoked on a witness stand, Perry, Paul Drake (William Hopper), Della Street (Barbara Hale), and sometimes Ham Burger and LAPD Lieutenant Tragg (Ray Collins) would always get together for coffee, dinner or a late-night office nosh to go over how Perry figured out yet another one.

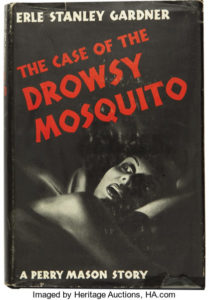

I came later to read some of the original Perry Mason mysteries by his creator Erle Stanley Gardner. In all there were roughly 80 such novels published between 1933 and 1973 (two years after Gardner’s death) and I know only one person who managed to read all of them after combing through used bookstores, tag sales, church basements and garages. Apparently, he finds them just as addictive as the old TV show. They can seem just as formulaic but, to their immense credit, just as unaffected and straightforward in their overall presentation.

“I write to make money,” Gardner once said, “and I write to give the reader sheer fun.” He called himself a “Fiction Factory” and he dictated his stories to typists, at least two or three books at a time, or so I’m guessing. Every once in a while, they read as if they were dictated and Gardner’s friend Raymond Chandler once wrote a note warning him of occasional discrepancies and inadvertent repetitions finding their way into published texts.

Even so, the Mason books are fun to read, as crafty, rakish, unflappable and droll as their hero. Burr’s interpretation of Mason retains the character’s almost eerie composure and serene command of the legal code to the point of breezy, but never brash arrogance.

Speaking of Raymond Chandler, here’s part of a morale booster he wrote to his friend Gardner in early 1946 that pretty much sums up how the world felt about Mason even before he became a TV icon :

“I regard myself as a pretty exacting reader; detective stories as such don’t mean a thing to me. [NOTE: THEY REALLY DIDN’T] But it must be obvious that if I have half a dozen unread books beside my chair and one of them is a Perry Mason, and I reach for the Perry Mason and let the others wait, that book must have quality….

“You owed nothing to Hammett or Hemingway. Your books have no brutality or sadism, very little sex, and the blood doesn’t count. What counts, at least for me, is a supremely skillful combination of the mental quality of the detective story and the movement of the mystery-adventure story….Perry Mason is the perfect detective because he has the intellectual approach of the judicial mind and at the same time the restless quality of the adventurer who won’t stay put. I think he is just about perfect…”

HBO’s Perry Mason, on the other hand, has plenty of brutality, blood, sadism and sex…all the lurid stuff that Chandler appreciated the Gardner books for avoiding. You could say it’s a lot closer to Chandler’s vision than to his friend’s. Try imagining, to press the point further, what Day of the Locust, Nathaniel West’s house-of-horrors vision of Depression-era Los Angeles would read like if Chandler had written it instead.

Having this iteration of Mason start out as a bottom-feeding private eye is at least consistent with Gardner’s roots as a Black Mask contributor of hard-boiled crime stories in the twenties and thirties. But devotees believed it altogether inappropriate to bring up the baggage of Mason being a shell-shocked WWI vet adrift and hopeless in 1931 Los Angeles, all too ready to dive headfirst into a Hooverville, a speakeasy or between the legs of his sultry Latina lover (Veronica Falcón). I suppose it’s possible to imagine this grimy, war-haunted vagrant evolving from the depths of the Depression into the coolly competent smoothie we remember from the dawn of the Space Age. In those latter days, we would never expect Mason to get into the kind of trouble this poor schlub endures.

Burr’s Mason, as noted, was like a sheet of ice on the sidewalk at night: too cold, too slippery and too devious to get stuck in mundane dangers like guns to the head or being roughed up and tortured by goons. What danger was for Mason, especially in the Gardner novels, was risking disbarment for – how did Della put it? – “stepping over the line” to prove his client’s innocence. The law for that Perry Mason wasn’t an occasion to be cynical; it was a near-holy order, a call to secular grace:

“I have never stuck up for any criminal. I have merely asked for the orderly administration of an impartial justice … Due legal process is my own safeguard against being convicted unjustly. To my mind, that’s government. That’s law and order.” – from 1943’s The Case of the Drowsy Mosquito.

Matthew Rhys’ Mason climbs up from the mire to where he’s supposed to be, eventually. There are hints throughout the series that he was always there, even if for much of the series he looks less like a budding smoothie and, in his still moments, like the ravaged, doom-haunted photos of James Agee taken by Walker Evans in the late thirties while they were struggling to finish Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.

The kidnap-murder of the infant boy and its ties to an evangelical church run by an Aimee Semple McPherson-style superstar preacher (Tatiana Maslany) is so sordid and complicated that you look forward to the light-and-lively banter among Mason, legal secretary Della Street (Juliet Rylance) and her cuddly, curmudgeonly boss Elias Birchard “E.B.” Jonathan (John Lithgow). But Mason can’t truly relax with them any more than he can figure out how to hold on to his family farm somewhere near the Mojave. Or figure out how he can get enough scratch for his keyhole-peeping to cover himself and his partner-mentor Pete Strickland (Shea Whigham).

But this apparent inaugural season isn’t about a dead baby, a glitzy temple or even a murder case whose thinness, wearing away even more during the trial, makes one wonder the same thing Murray Kempton wondered while covering New York City’s (Black) “Panther 21” trial in 1971 after the prosecution rested its case: “And is it all no more than this?” (from Kempton’s The Briar Patch, 1973). It is, in short, not about the central mystery at all. It’s about the growth of a human being.

“And is it all no more than this?” you may well ask. Quite a bit more, especially at this point in our own real-life history.

Let’s do what we always do in a Perry Mason story and look for clues. To me, the biggest clue comes towards the end of the first episode, when a movie mogul and Groucho Marx look-alike takes Mason into a back room and has him trussed up by a couple of goons, shaking him down for the compromising photos he took of a naked horndog comedian. “You need to think about your actions,” the mogul purrs to Mason who’s about to get a heated gun barrel applied to his chest. ”You need to decide what kind of person you want to be.”

The protests we’ve been seeing since May throughout the country over police brutality and systemic racism have been asking variations of the same question. And it’s been hurting us to ask that of ourselves, about as much as that hot rod is hurting Mason.

It’s worth remembering here that Erle Stanley Gardner shared the same view of justice vs. law-and-order that his lead character did. His early career as a litigator was taken up with defending underdogs, often Mexican and Chinese immigrants, who he believed were unjustly indicted and couldn’t afford the defense they deserved. In the early forties, he formed an organization, “The Court of Last Resort”, devoted to helping those imprisoned unfairly or couldn’t get a fair trial. Both a prize-winning book and a short-lived TV series carried the name and the mission of Gardner’s precursor to today’s Innocence Project.

Maybe watching Rhys’ Mason, as opposed to Burr’s, struggle, stumble, whine and grumble his way towards his ultimate destiny is an analogue for our own halting, stumbling and grudging efforts to restore balance and fairness to our legal system. And while Gardner, if he were alive today, would likely shudder over just how much of a mess the American criminal justice system has become, he would likely put his man, high-handed tactics and all, in the forefront of setting it all right again.

From the apparent success of the HBO series, we’re going to see more of this new/old Mason, and it’ll be interesting to see how or if his self-improvement continues as his cases get as weird or weirder than the ones his predecessors dealt with on- and off-screen. I’m also wondering just how the producers are going to finesse a Black Paul Drake (Chris Chalk) trying to pry buried secrets from white people in an L.A. mired in Depression, impending war and racial segregation.

No, it’s not your father’s or grandfather’s Perry Mason. But this stressed-out, caffeinated and volatile Perry Mason belongs to us more than we’re willing to acknowledge. He knows we’re all guilty. But that doesn’t mean he’s giving up on us. So don’t give up on him.