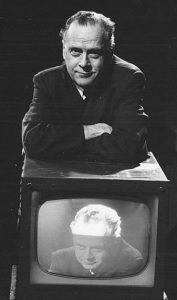

I discovered Marshall McLuhan where you were supposed to: on television. It was during the late winter of 1967 in what was in those days referred to as the Sunday afternoon “ghetto” for “highbrow” programming. The series was called NBC Experiment in Television and it featured everything from absurdist theater to unknown Black writers in Watts workshopping their poetry and prose. Even then, my teeming high-school-age brain was a sucker for eclecticism served up fresh and hot and that lizard brain somehow seemed especially primed for a white middle-aged Canadian college professor shooting off aphoristic sparklers about my best and most faithful pal, TV, and why it mattered.

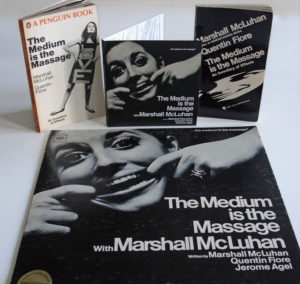

The show was called “This is Marshall McLuhan: The Medium is the Massage” which was basically a filmed adaptation of the paperback book with the same title (the latter half, anyway) and whose hip, flashy visual design was laid out by Quentin Fiore. But the book and the documentary ramped up the heat on McLuhan’s then-burgeoning fame for his ideas about “hot” and “cool” mediums; how electronic media has all but overrun print’s autonomy over civilization and that mass communication has transformed the world into a “global village” that is, as McLuhan characterized it in the film and elsewhere, “as wide as the planet and as small as a little town where everybody is engaged in everybody else’s business.”

I was so dazzled by it all that I not only secured a copy of that slick little book as soon as I could get my hands on it, but I wrote my senior AP term paper on McLuhan three years later. On a typewriter, of course, because who knew from computers back then except as those big blocky things with magnetic tape at my father’s workplace. (He, by the way, dug most of what McLuhan was laying down on that NBC special, even if he wasn’t entirely sure of all the specifics.) I ended up reading some of the McLuhan books with no pictures like Understanding Media (1964) and even The Gutenberg Galaxy (1962). even if I ended up cherry-picking my way through the latter for material that I found mostly to be similar, at times word for word, as the later book.

Which was a big reason why my teenage self connected with him. Even without pictures and fancy graphics to augment it, McLuhan’s prose was what many readers, pro and con, called mosaic-like; I’m guessing what they meant was the way his oracular, inscrutable assertions and observations swooped, doubled back, and swooped again (in case you didn’t get them the first time) in flashy, sometimes puffy and dense, but riveting patterns, much like the panels in the Marvel comic books I was devouring at about the same time. He kept you reading for the same reason as Tom Wolfe, one of his first promotors (“What If He is Right?”). Put a toga on him and the Romans would have had to invent their own word for “beatnik” to classify him.

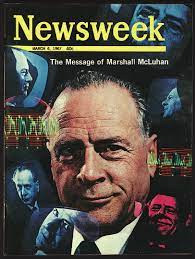

Even at the time I wrote my school paper, he was getting divebombed by scholars and various other defenders of the status-quo believing him to be too slick to be taken seriously. They thought he was a charlatan, spinning the kind of buzzy phrases (“hot” and “cool” mediums, “global village,” “participation mystique,”) that only baby boomers and the advertising agencies that catered to them could embrace as higher wisdom. I might even have mentioned some of these qualms in my paper, though I’m sure that if I did, I chose to give them cursory attention.

Still, for most of what was left of the 20th century, cursory attention is what I mostly gave McLuhan and his vision of the future. Like everybody else who saw Annie Hall in 1977, I was charmed by Woody Allen dragging him from off-screen to suavely scold the obnoxious pedant waiting in line to see a movie about knowing “nothing of my ideas,” even though in the years since, I’ve wondered how much space in the soul of that same movie’s writer-director-star is rented by said pedant. The year before, I remember being pleasantly surprised that McLuhan’s observations of the Carter-Ford presidential debate, as registered the morning after on the Today show, were as sour as my own.

But as the 20th century wound down and the 21st began, McLuhan himself seemed less present in the culture than his observations – most of which, thanks to the Internet and its myriad spoils, were coming true. As one writer put it, we were too busy living out McLuhan’s prophecies to go back and read them. Or watch them.

Until I did, for the first time in over fifty years. It’s no longer a matter of, as Tom Wolfe asked, “What If He Is Right?” It’s how “right” is he? Watch the show above. Now watch this excerpt from a 1966 interview. Think he’s just talking about TV? He’s also talking about the Internet…and AI!