March 7th, 2013 — on writing lit -- and unlit

Ta-Nehisi Coates got his inevitable close-up in this week’s New York Observer and, as anyone who’s followed his work on- and off-line in The Atlantic will tell you, he deserves all the love he’s getting here. He has the grace to be embarrassed by these garlands – which of course only makes him worthier of them, especially when the one encomium that makes him cringe the most is being labeled “the best writer on the subject of race in America.”

While it’s true, as articles like this (from last fall) or this (more recent) make radiantly, abundantly clear, that Coates can slice through racial cant with this dude’s ruthless efficiency, even a casual tour of Coates’ blog site discloses his facility with such subjects as history, politics, sports, science and music. Cultural arbiters will insist that, however eclectic his interests, they are filtered through an African-American point-of-view. Well, yes. He’s a young African American and he has points-of-view that are informed by his life experiences. But what if he chose to write solely (and with comparable grace and precision) about, say, chess or music videos or physics or economics? Would his mastery of these subjects be recognized, much less lionized? Probably. We live, after all, in a world where black writers become famous on TV for being sports journalists and a film reviewer-of-color receives the Pulitzer Prize, just for being excellent and eclectic.

Still, African American writers remain the default setting for editors seeking that all-important-all-encompassing “black perspective.” And that’s by no means an inconsiderable, or unnecessary thing. There are things we know, feelings we have access to that white editors and writers don’t. We ask the questions that others may not. Our loyalty and devotion to our race confers a responsibility to enlighten our white country-persons if only to make sure they don’t assume, presume or otherwise say (or do) something stupid, insensitive or ill-informed to and/or about us. Still, why should Being Black be the one-and-only-thing about which we are always counted on to deliver an informed opinion?

Coates shouldn’t have to fall into a “spokesman-for-his-people” niche conferred by whatever passes for a post-millennial media establishment, though the risk is always there. That unofficial pedestal prevented my adolescent self from fully appreciating James Baldwin back in the 1960s when I too often thought he was speaking “for” me rather than “to” me. (It’s only as a much older adult that I’ve come to value Baldwin as the visionary essayist and undervalued novelist he was at his peak.) As master of the blogging art, in emceeing and in posting, Coates has more space than his predecessors did in trumping and deflating any attempt to make him The Black Spokesperson; it also helps that he’s been generous enough to give his peers some props, something too few of our predecessors did in a more competitive era.

But black writers shouldn’t always have to be the go-to source for writing about race. Indeed, some of the finest nonfiction on this topic has come from Caucasian writers as well. Larry L. King, whose recent obituary saw fit to highlight his collaboration on a successful little musical about Texas hookers, wrote a brave, candid essay, “Confessions of a White Racist,” that was expanded to an even better memoir. And I’m now in the midst of re-reading Joan Didion’s “Sentimental Journeys,” her exhaustive and masterly 1990 report about the hysteria surrounding the 1989 rape and near-murder of a white woman jogging in Central Park. Having seen Ken and Sarah Burns’ recently-released, award-winning cinematic j’accuse, Central Park Five, I now find Didion’s epic dissection of the crime and the subsequent police investigation, arrests, convictions and warring points-of-view to be one of the most cogent examinations of how race, class, politics and hype conspire against simple justice – and, given how things turned out with those five convictions, Didion also proved how steely and forbiddingly prescient an observer she is. Could any other writer, black or white, have shown as much composure at a time when emotions about the case, for and against the original convictions, were still strident and raw? I can usually imagine almost anything I want, but I’m having trouble with that one.

Sometimes, I think everything you write about when you write about America is about race – except when it isn’t. (And when it isn’t, I’m tempted to think the writer’s trying to hide something.) But as Coates as written, it’s in the particular rather than in the general that a writer can find her true voice on this volatile topic. When the voice reaches too far, too hard and too broadly, bad things tend to happen. I shall let the Best Writer on The Subject of Race have the last words:

“No one who wants to write beautifully should ever — in their entire life — write an essay about ‘the subject of race.’ You can write beautifully about the reaction to LeBron James and ‘The Decision.’ You can write beautifully about integrating your local high school. You can write gorgeously about the Underground Railroad. But you can never write beautifully about the fact of race, anymore than you can write beautifully about the fact of hillsides. All you’ll end up with is a lot of words, and a comment section filled with internet skinheads and people who have nothing better to do with their time then to argue internet skinheads.”

February 25th, 2013 — movie reviews

Here are some things I didn’t have time or space to squeeze into this CNN thingee. (I had to sleep sometime after all):

1.) Watching some of “Jimmy Kimmel Live” last night & noting how the post-Oscar cast was more enjoyable, and a tad funnier, than what it followed (& that includes Your Local News), it occurred to me that all awards shows, except maybe the Tonys, will have to become desk-and-couch affairs if they expect to survive as annual broadcasts. I know historians now regard David Letterman’s turn-at-bat as a cataclysmic whiff. But imagine how he’d have done if he’d been in his comfort zone with Paul pouring the necessary smarm over everything. It may be another ten years or so before that happens, by which time desk-and-couch shows will be as obsolete as analog phones.

2.) If this year’s producers were so damned anxious to have a Broadway feel to this thing, why didn’t they just call Neil Patrick Harris to the captain’s chair & let him go nuts? He & Billy Crystal may be the only two people alive who know how to go meta with this glitz while still respecting it as glitz. Good luck boosting next year’s ratings.

3.) You know what was even more enjoyable than Kimmel or the Oscars? Cruising Facebook & Twitter for immediate reactions to last night’s awards. Maybe the future will really involve people showing up on red carpets in fancy clothes before heading into chat rooms to tap out the individual impressions through their FB pages or shoot their own video. The Academy will take care of the rest by mailing out the statuettes in advance. In Anne Hathaway’s case, at least, I though they did, anyway.

4.) I wasn’t surprised that both Lincoln and Zero Dark Thirty got relatively shut out, even though I thought right up to the end that the hacks respected Tony Kushner’s ability to effectively dramatize difficult material. Instead, the hacks got theirs by raising a middle finger to those who slapped Quentin Tarantino upside his head for turning slavery into, if you will, pulp fiction. (As I told CNN, wait twenty years…)

5.) Paraphrasing Oliver Stone, there’s the way America is & the way we ought to be. Argo, as I wrote in my CNN piece, was the way Hollywood & America prefer imagining themselves while Lincoln, The Master and Zero Dark Thirty reflected, in different ways, what they, and we, really are. That the Academy voters let controversy (or at least its prospect) get in the way of acknowledging those movies suggests that even the opposite edges of the continent are as polarized & tied-up-in-knots as the rest of America.

6.) People ooh-ed and aah-ed over Michelle Obama’s hook-up with Jack “King” Nicholson. (She has that effect on people, especially after she did the hippy-hippy-shake with Jimmy Fallon last week.) What I was hoping for, ever since last summer, was an excuse to put Clint Eastwood on stage last night and have Michelle’s husband show up in a chair off to Eastwood’s left. “Did you have something to tell me?” the president would have asked in, of course, the nicest possible way. A braver world than this would have allowed it to happen. As last night awards made clearer than ever, we do not live in a brave world, except when we’re tossing snark through our keyboards. In the meantime, I love you, Amy Adams & wish you better luck next time.

February 17th, 2013 — movie reviews

Not to press the point too hard, but for those who’ve seen Django Unchained and still wonder, or even care, about its relative closeness to historical authenticity, there is this much about which they can be reasonably assured: Most white folks were as serious as cancer about not letting black people ride horses. Didn’t matter if they were free or not. After all, if slaves see other colored people on horses, they may start getting…ideas. Livestock wasn’t supposed to have ideas. And livestock wasn’t supposed to be riding on top of other livestock either. Silliest damned thing a southern planter with any wits about him could bear to imagine. Like having a goddam goat riding a pig! Now don’t that sound wrong as hell?

Livestock: Let’s be emphatic, shall we, as we “observe” yet another Black History Month. It didn’t matter way back when whether the black people looked like Kerry Washington or Oprah Winfrey, like Jamie Foxx or LeBron James, like the incumbent president of the United States or his stunning wife or their two lovely daughters. If they were in the American South before 1863, they were all livestock and not even papers claiming their freedom could ensure that they wouldn’t be arbitrarily tossed into a corral, roped, branded, chained and treated only a feather or two better than the chickens.

If you’re livestock and leave the corral, they’ll put you in a cage. And you don’t ride anywhere unless the cage somehow rides with you – or you walk behind any white man on a horse, even if that white man is stupider than you, or his horse.

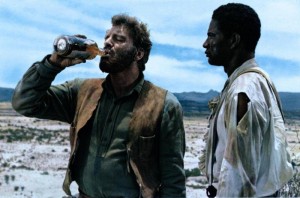

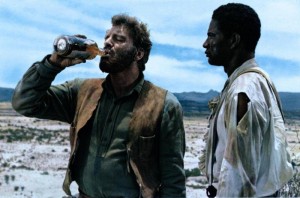

A movie, I say with mild embarrassment, first placed this gross disparity before my callow sight line. The Scalphunters, released in 1968, was the third feature film directed by Sydney Pollack, a name I’d recognized from some quirky television work as well as a feature he’d directed three years before, The Slender Thread with Sidney Poitier and Telly Savalas as psychiatric caseworkers trying to save Anne Bancroft from suicide. This particular movie was a western with another intriguing interracial star pairing: Burt Lancaster as a fur trapper and Ossie Davis as an educated fugitive slave he’s forced to acquire as compensation for the pelts he loses to a group of cagey, sybaritic Kiowa.

The trapper, Joe Bass, rides off after the tribe while making the slave, Joseph Lee, stumble along the trail after him, mostly on foot. Joe is, after all, a man of his times and those times dictate that he should eventually sell off Joseph Lee to whomever offers the best price. To his credit. Joe does let Joseph Lee ride the horse just long enough for the latter to attempt a getaway. One whistle from Joe and the horse tosses the disconcerted slave from the saddle. (Bass: “You seem to have an uncommon prejudice against service to the white-skinned race.” Joseph Lee: “I don’t mean to be narrow in my attitude.”)

When they catch up with the Kiowa, they’ve pretty much emptied Joe’s whiskey supply. “You ever fight twelve drunk Indians?” Joe Bass asks Joseph Lee. “No, sir,” the latter replies, “but I’d like to see it done.” But before that show can start, it’s pre-empted by marauders roaring and slaughtering and relieving the tribesmen of their scalps and of Joe’s purloined furs. Joe Bass considers the genus of outlaw making money off dead Indians’ hair to be “the wickedest, crookedest trade to ever turn a dollar.” Joseph Lee, who intimately knows an even more wicked way of making money, can only stare back in what seems to be incredulity. We’re not quite sure how long before the Civil War this tale is set. (I’ve read some accounts that place it in 1860.) But we know by this point that Joseph Lee’s smart enough to keep his counsel here.

Still, for the first part of the movie, you wonder how Ossie Davis maintains his own composure. At the time this movie was made, Davis had achieved international esteem as both an actor and a writer with a successful play, Purlie Victorious, in his resume. He’d also established considerable credibility as an activist and was the principal eulogist at Malcolm X’s funeral in 1965. One was used to seeing Davis by the late 1960s, in varied roles on-screen – save for a leading one, despite his magnetism and warmth. Despite his reputation, Davis was billed beneath Lancaster, Shelly Winters and Telly Savalas. So however shrewd the movie’s tactics were, he must have thought a little harder than usual about the idea of playing in an antebellum comedy-western in which the only role available to him would be that of a runaway slave, albeit one who spent most of the movie choking down rage and humiliation with foxy erudition and oneupmanship.

Keep in mind, also, that the year this movie was released (the same week that Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered in Memphis), Davis was in the vanguard of a wave of African American writers publicly chastising William Styron for writing what they believed to be a facile (at best) novel about Nat Turner and his 1831 slave revolt. At the time, many of these writers, including Davis, were asked why they hadn’t written a novel or play about slavery. Davis, I seem to recall, at least acknowledged that he hadn’t written his own work challenging Styron’s vision — though he would in 1969 appear in a movie, Slaves, memorable, if at all, for being Dionne Warwick’s first — and last — starring role in a motion picture.

Davis didn’t have to perform in that silly, overwrought movie or write his own play or book to contribute to the culture’s evolving view of American slavery. If he wanted to make his own response to Styron’s Nat Turner, either as correction or counter-text, his Joseph Lee was more than enough. Within minutes of his appearance on-screen, Davis lets you see his character’s cultivation, grace and instinctive ability to tame the savage white man. You also see his wit, dignity and, as noted, his slyness. The joke of a black slave being smarter than the he-man white hero made for a nice gimmick in the years when multi-racial casting in westerns was still a relative rarity; westerns themselves now being relative rarities. Indeed, the white male characters in Scalphunters, including the marauders’ bonehead ringleader Jim Howie (Savalas) are nowhere near as smart as Joseph Lee, the crafty Kiowa chief Two Crows (Armando Silvestre) and Howie’s sassy significant-other Kate (Winters, sultry and kittenish in what was likely her last sex-bomb role).

But there’s a point in the movie – a sharp, glistening point – when Davis emerges as much more than a clever plot device. It comes as Joseph Lee, having accidentally fallen into the marauders’ camp and then finagling his way into accompanying them to the Mexican border, goes back to where Joe Bass has been a one-man guerilla force in pursuit of his pelts. He greets Bass’ hostility with both a supplicating smile and a bottle of whiskey from Jim Howie’s private stock. “I thought,” Joseph Lee grins, “you could maybe use a drink about now.” Bass takes the bottle with contempt for the way Lee accommodated himself with the gang, not even bothering to acknowledge Lee’s facility for survival – or his urgent need to go to a country where there is no slavery All Joe can say of Joseph’s resourcefulness is: “Throw you in the pig pen, you’d come out vice-president of the hogs,” he spits. (See? Livestock…)

When Joseph then asks if he could have a sip, Bass snarls back, “If I was to give you a drink of this whiskey, it’d be like pourin’ it out in the sand. This is a man’s drink. And you aint no man. You aint no part of a man. You’re a mealy-mouthed shuffle-butt of a slave and you picked yourself a master. So don’t go askin’ to take a drink with a man.”

At that dreadful moment, all of Joseph Lee’s canny defense mechanisms vanish, exposing a shaken, wounded, and somewhat volatile visage. It’s as if Bass’s cruel words yanked away the slave’s shirt to expose the scars of several dozen lashings, not all of them physical. Davis makes his face register a host of warring emotions before it changes into something harder and tougher than what the audience, up to that point, had been accustomed to seeing. As with the greatest actors, he does this before you’re even aware that it’s happened. And Davis, make no mistake, was one of our greatest actors.

Joseph, recovering his voice, lowers it. He tells Joe Bass just how small and stupid he really is, without using either of those words. And then he says, “You know how long you’d last as a colored man? About one minute.” That single line does the work of several-hundred words of steamy, hopped-up rhetoric by Leonardo DiCaprio or Christoph Waltz in Django about the ingrained distortions of humanity that remain the principal legacy of America’s Original Sin. Before long, the two of them will end up slugging each other in a mud hole, only to ultimately be left behind yet again, with one horse, no furs and no passage to freedom. The difference is that, this time, they both wear brackish, grayish coatings of caked, wet dirt. With no color distinctions between them, they’re just another pair of wayward desert flotsam.

Back in 1968, there were some who likely believed such an ending rubbed the audience’s faces in social consciousness, so to speak. Yet I’m willing to bet if any contemporary Hollywood movie tried the same approach, some would say they were being too subtle. A movie like The Scalphunters could take its time, keep things light, make its points by stealth. Now some would wonder if it’s being too frivolous. As the many Joseph Lees in history who made up their beings as they went along would tell you, there are as many ways to be tough and resilient as they are to telling stories. This crafty little movie, which somehow got lost in an emergent wave of boundary-busting Hollywood films, deserves our attention for making that deceptively simple point.

January 29th, 2013 — movie reviews

IMMEDIATE REACTION: I know what you’re thinking. At this late date, who am I to put twigs on a fire that’s dying out anyway? After all, nobody cares a fig what I think about torture. I’m not sure I care either. It’s like what Randy Newman said about the Spanish Inquisition that “put people in a terrible position/I don’t even like to think about it/Well…sometimes I like to think about it….”

1.) I’m just going to throw this out: The Hurt Locker is a better movie, though there are stretches of righteous filmmaking in this one; not surprisingly, they all come as the movie approaches the precipice of shattering violence. (The build-ups to both bombings, especially the Christmas morning attack; the whole climax, etc.) It’s not entirely Kathryn Bigelow’s fault any more than it’s Jessica Chastain’s fault that she’s stuck playing not a character so much as a state-of-mind. (More on this in a minute.) To me, doing this story so soon is like someone making JFK in 1966 — and something tells me if Oliver Stone were able to do so back then, he would have. Even before the movie was released, I was wondering what the rush was to get this story on-screen, irrespective of the controversy over torture. (More on THAT in a minute, too.) If I chose to practice armchair psychology (& since it’s just us talking, why not), I’d guess that K.B. was drawn to the idea of a brilliant, ballsy young heroine whom no one — no MEN, specifically — takes as seriously as she demands to be taken. (I’d love to see K.B. someday do HER side of James Cameron’s The Abyss, though it wouldn’t necessarily have to be the same story.) I think Zero Dark Thirty is taking a beating mostly because its narrative is still current enough to be mistaken for journalism where if it were made and/or released ten or twenty years from now, the movie would be viewed correctly as historic events filtered through imagination. It may take twenty years for that to happen anyway.

2.) By now, I’ve read & heard just about every attack on Zero for its depiction of torture; that it glorifies or misrepresents torture as being key to getting a lock on Bin Laden’s whereabouts or is shilling some kind of thinking-person’s version of “USA! USA! USA!” triumphalism. (For balance’s sake, I shall include both Greg Mitchell’s measured dissent of the movie in his Nation blog and Glenn Kenny’s elegant and thorough skewering of the movie’s attackers.) As I’ve already said, I think the movie kind of asked for the pummeling it’s getting by throwing all this stuff out there unmediated by time’s passage & the intervening revisions & disclosures that could broaden understanding of the whole War-on-Terror era. But if the leftist pundits out there truly believe that the movie’s audiences are going to watch these waterboarding-and-boxing-in scenes & feel in any way ennobled or roused by the CIA’s savvy, then it sounds to me as though they’re not only underestimating people’s intelligence (to say nothing of their capacity to be grossed-out), they’re sort of buying into the blinkered bullshit about the Power of Movies without any real knowledge, intuitive or otherwise, of what that Power really is. (Getting back to JFK, do you really think that movie changed anybody’s mind about whether or not Oswald acted alone? If anything, that movie bullied people into thinking, “Who cares anymore who killed Kennedy?” — just as, it could be argued, Spike Lee’s Malcolm X swallowed or exhausted whatever public acrimony or controversy remained about its subject, too.)

3.) And as for the triumphalism, I REALLY don’t get where that criticism comes from. You most emphatically do not walk away from Zero Dark Thirty feeling cleansed, cathartic or especially patriotic. If anything, it comes across as an anti-revenge revenge movie, if that makes any sense. From the very beginning when you hear the wailing of the soon-to-be-dead woman in the soon-to-collapse Twin Towers to the very end when you see Chastain’s Maya, isolated on a transport plane she has all to herself, weeping & desolate & not quite sure anymore who she is or where she goes from here, Zero Dark Thirty resounds as nothing so much as a melancholy dirge on America in the ten years between the raids of both 9/11 and 5/1; of what we became or compelled ourselves to become in the wake of a heretofore unimaginable trauma. (This review, from what seem like eons ago, puts it better than I just did. )Maya is the embodiment of that mind-set, a blank space upon which we’re supposed to project our own seething desire for closure or payback. She doesn’t have any past except the one we’re supposed to conjecture. (Did she have some connection with the woman on the phone in that 9/11 prelude? I haven’t read anything that suggests that, though I’m sure it’s out there somewhere.) That Chastain makes this enigma substantial enough to carry this movie is, I suppose, reason enough to give her an Oscar nomination. Still, a blank space is no substitute for a real person & not even that moist coda she delivers is enough to make me believe in her. She likely had less to work with in The Tree of Life & she somehow evoked everything about that mother’s past, present & future. I guess if Zero does anything for her, it’ll make her a convincing starship captain in some Star Trek sequel, assuming she ever wants to go where no method actress has gone before.

4.) So little does Zero troll for patriotic cheers that I think it hurts its own chances for collecting any Oscar whatsoever. Argo. Now THERE’S a movie that makes you stand up and go “USA! USA! USA!” at the end. It’s the principal reason the Academy now regrets not giving Ben Affleck a director’s nod & why it now looks as though his movie’s poised to eat everybody else’s lunch, even Abe’s. Just as Rocky trounced All the President’s Men & Network in 1976 & Crash beat out Brokeback Mountain in 2006, the movie that makes Hollywood feel better about itself will likely clobber the movies that feel too much like Homework. (Remember: I’m forcing myself not to care this year who wins what…)

January 8th, 2013 — movie reviews

NOTE: I’ve also written a piece for CNN.com covering most of the same ground here. If you want to compare or contrast, click here.

IMMEDIATE REACTION: If loving Django Unchained is wrong, then I don’t…well, let’s see. What is it exactly I don’t want to be? That is the question. One of many…

Let’s tip off with a question that may not have an immediate or easy answer: Which movie better empowers black audiences? An historic drama, more or less factually-based, in which white men argue over and eventually move towards ending slavery – if not racism? Or an historic fantasy, rife with vulgarity, anachronism and impropriety, in which a freed black slave lays waste to every white southerner impeding his reunion with his wife — and gets away with it?

I am not asking which is the better movie, Lincoln or Django Unchained. Both have their problems. But it’s possible, despite their flaws, to enjoy them both for what they are, while accepting what they are not. I did not expect Lincoln to be much different from any other Steven Spielberg movie (though, until the ending, it is) and I certainly didn’t expect Django to be anything other than a Quentin Tarantino movie (and it is, only more so, for better and worse.)

For whatever it’s worth, my issues with the movie have more to do with craft than substance. I think Django talks too much, even for a Tarantino movie; and I also think that many of its scenes go on for too long, almost as if the movie’s afraid to let go of whatever effect it thinks it’s making with those people in the dark. It occurs to me, as well, that Tarantino’s been ripping himself off too cavalierly. I watch the set-pieces of wholesale slaughter and think, if I didn’t know any better, I’d swear I was watching Kill Bill Vol. 1 and the Japanese have been turned into southern whites.

Still, I couldn’t help myself. I laughed at Don Johnson and his night-riding stooges throwing hissy fits over whether to keep their masks on. I was almost touched by the slave girl’s impromptu bon mot aimed at Django’s baby-blue fop’s outfit. “You’re free…and you want to dress like that?” I didn’t buy any of it. But I was into it. And part of me hates myself for it. But I’m not sorry I saw it.

All right, then. So what am I asking? Get comfortable. I’m going to digress.

Back in 2006, I reviewed Blood Diamond for Newsday, giving it the two stars I routinely doled out to generic Hollywood mediocrity. I acknowledged the importance of the movie’s theme, which was the exploitation and wholesale murder of black Africans for the sake of the pink diamond trade. But I found myself chafing over the way this movie, along with so many of its kind, depicted its dark-skinned characters “as wholesale cannon fodder, doomed-but-noble ciphers or sneering bloodthirsty sociopaths.” I also lamented how the always-exemplary Djimon Hounsou, cast as a fisherman from Sierra Leone searching for his captured son, was used mainly as a vehicle through which the morally indolent white mercenary played by Leonardo DiCaprio Finds His Humanity (or something like that). At one point, Hounsou’s character even wonders aloud whether his people’s black skin constitutes some sort of curse “and [that] we were better off when the white man ruled.” No one, certainly not DiCaprio’s character, bothers to engage, much less contradict, this query. And, of the movie’s critics, I recall only the Nation’s Stuart Klawans calling the movie on this odious hogwash.

This is how I ended my own review:

“I suppose we should be grateful that there have been so many commercial features in recent years (“Hotel Rwanda,” “The Constant Gardener” among them) that pay attention to Africa’s woes. But even the best of them seem to writhe from hopelessness to despair and back again. Maybe what the continent needs are some empowering pulp myths far beyond the hoary model of Tarzan. A good start would be to cast Hounsou as the lead in a movie about the Black Panther, Marvel Comics’ first superhero-of-color. An African king who’s both a world-class physicist and a supreme martial artist may not be plausible, but he could broaden moviegoers’ sense of what’s possible.” (ITALICS ADDED).

Some readers, at least those who got that far, seemed to have a problem with this notion. One used the word, “infantile” (which over time I’ve accepted as a back-handed compliment). But what is so childish about African American audiences wanting their on-screen counterparts (or surrogates) to be more than merely victims? I believe even white audiences get excited when conventional expectations, especially in race and cultural matters, are upended, if not exactly transcended.

This is the excitement I hear from people after they’d just seen Django Unchained. I doubt whether any of these viewers bought their tickets with the expectation of seeing some historically faithful saga of antebellum life, and neither did I. They were buying a comic book. Many people have a grievance against the very notion of comic books, but I don’t. I understand that comic books as a medium are limited in what they offer their clientele. So are the movies, especially those who cruise the multiplexes for loose coin. Expect a movie or a comic book to explain everything about anything and all you earn is surplus sadness in your life that you don’t really need.

Even with the narrowest expectations about historical veracity, however, things get complicated when the subject matter is American slavery, European Holocaust or any number of similar assaults upon humanity. Hence the reaction to Django, after less than a month of swimming in the mainstream, ranges from sheer exhilaration to outright hostility, with the usual gradations in between.

Much of the resentment seems aimed exclusively towards Tarantino himself; a visceral dislike which I think has a lot to do with Spike Lee’s outright refusal to see the movie, tossing grenades at it all the way. Ishmael Reed, writing in the Wall Street Journal, believes Tarantino shows willful, if not willed ignorance of history, both American and cinematic. He writes: “To compare this movie to a spaghetti western and a blaxploitation film is an insult to both genres. It’s a Tarantino home movie with all the racist licks of his other movies.” Reed aimed this laser shot at the Oscar-nominated actor who plays the treacherous “house slave”: “Samuel L. Jackson…plays himself.”

I doubt Jackson felt the blow. He has, in fact, further provoked the movie’s antagonists by running straight at an interviewer asking about the movie’s prolific use of the “N-word,” refusing to answer the question unless the reporter, who is white, actually says the dread epithet aloud. (He didn’t.)

Though I disagree with Reed’s conclusions, I think everyone who saw Django should read his piece for its flying shrapnel of loose insight and, most important, its disclosure of what has always been a relevant source of disquiet: The debate over whether white artists have the right to tell any part of the black American story – which, as Reed writes, is as old as Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

It is also as recent as 1967 when the white southern novelist William Styron published The Confessions of Nat Turner, a Pulitzer Prize-winning novel told in the first-person voice of the brilliant-but-doomed leader of an 1831 slave rebellion. The outcry from African American novelists was so intense that a collection of essays, William Styron’s Nat Turner: Ten Black Writers Respond was published a year later. When I was a credulous, anxious-to-please teenager, I was so in thrall to the authority exerted by those black writers that for decades afterwards, I refused to even go near Styron’s book.

I still haven’t read it. But I plan to, because I now believe that James Baldwin, a friend of Styron who was one of the few African American authors speaking out on the book’s behalf, had the right take from the beginning: “I will not tell another writer what to write. If you don’t like their alternative, write yours.”

It’s still sound advice – and in the intervening years, black authors have taken it. Indeed, if anyone’s earned the right to rail at Django, it’s Ishmael Reed since, unlike Spike Lee, he’s actually created his own antebellum thriller that’s as funny, provocative and calculatedly anachronistic as Tarantino’s. I can almost hear Reed erupting with outrage over the sheer notion of my comparing Django with his 1976 book, Flight to Canada. But as I insisted to friends and fellow readers at the time (and continue to do so), even with all its musical-comedy interludes, burlesque elements and television cameras, Reed’s shrewd take on the slave-narrative genre had more trenchant, telling and useful things to say about the Peculiar Institution than Alex Haley’s Roots, which was ascending, that same year, to the rare stature of pop-cultural phenomenon. When Haley’s book became a television mini-series, it affected America’s racial attitudes as nothing of its literary kind since…Uncle Tom’s Cabin. No one’s bothered to do anything with cinematic Flight to Canada. Or, for that matter, with Charles Johnson’s Oxherding Tale and Middle Passage, two other antebellum satiric adventures written by an award-winning black author.

In 1987, there was Toni Morrison’s Beloved, which did get adapted for the big screen eleven years later by Jonathan Demme. But even with Oprah Winfrey’s imprimatur as producer and co-star, the movie earned about $26,000,000, roughly half of its $50,000,000 budget. And while all I have is anecdotal evidence, I remember many of my African American relatives and friends who told me they were not going to see Beloved, no matter how good it was or who was in it, because they simply did not want to watch a movie about slavery, or its legacy.

This reluctance to engage with the subject of slavery is duly noted in Jelani Cobb’s ruminative take on Django:

“In my sixteen years of teaching African-American history, one sadly common theme has been the number of black students who shy away from courses dealing with slavery out of shame that slaves never fought back. It seems almost pedantic to point out that slavery was nothing like this. The slaveholding class existed in a state of constant paranoia about slave rebellions, escapes, and a litany of more subtle attempts to undermine the institution. Nearly two hundred thousand black men, most of them former slaves, enlisted in the Union Army in order to accomplish en masse precisely what Django attempts to do alone: risk death in order to free those whom they loved. Tarantino’s attempt to craft a hero who stands apart from the other men—black and white—of his time is not a riff on history, it’s a riff on the mythology we’ve mistaken for history. Were the film aware of that distinction, Django would be far less troubling—but it would also be far less resonant. The alternate history is found not in the story of vengeful ex-slave but in the idea that he could be the only one.”

Cobb’s ambivalence approaches my own point-of-view, even though I still liked the movie better than he did. As with other critics, he laments Django’s lapse into revenge-movie mode. I lament the fact that almost EVERY big-studio film is built for revenge, even romantic comedies. (What, after all, is Skyfall but the mother-of-all-revenge-fantasies with different agendas for vengeance overlapping and colliding into each other like a freeway pile-up?) No matter. If Django Unchained did nothing else but arouse re-examination of “the mythology we’ve mistaken for history,” then all the trouble and fuss it’s caused will have been worth it.

January 2nd, 2013 — family history, jazz reviews

For our site’s inaugural posting of 2013, I proudly & happily yield the floor to Chafin Seymour (BFA, Dance, The Ohio State University, 2012), who has picked up his father’s end-of-the-year compulsion to assess the things he hears and let the world in on what he thinks of them. Unlike his father, he does his list, you will note, in ascending, rather than descending, order (“Opa Letterman Style!” And, no, you wont find no damn Psy on this list.) He also shows righteous critical acumen that, were I an overly envious person, would make my teeth ache. Instead, “my heart soars like a hawk”! (Name the movie. Win no prizes.) It would seem I have helped re-birth Lester Bangs, though he dances a whole lot better and takes better care of himself…I hope.

These are my top albums of 2012. I will not go overboard with my intro except to say that 2012 was an exceptionally strong and eclectic year in independent and pop music, and I had a hell of a time deciding what I wanted to write about for this year end wrap-up. I decided on these fourteen albums (four honorable mentions and a top ten) arduously and carefully.

Honorable Mention

Killer Mike – R.A.P. Music

Cagey rap veteran Killer Mike finally does his name and reputation justice. Independent, political, and fiercely opinionated, Mike makes the album we have been waiting for, with help from Brooklyn producer El-P, who takes some of the usual distortion out of beats in favor of banging southern bass. It is a smart choice that allows Mike to rock in his comfort zone from start to finish.

TNGHT – TNGHT EP

THE party record of the year, hands down. This five song EP from producers Lunice and Hudson Mohawke was a giant smack across the face of modern dance music. Combining “trap” style southern hip-hop bass with elements of House and Dubstep (note the intense-ass-drops on every track), TNGHT reveled in simplicity and space while urging pop consumers and club kids to “wake the f’ up” and notice some real “ish.”

How To Dress Well – Total Loss

This was the first proper cohesive album from How To Dress Well’s Torn Krell. He continues to play with traditional R&B arrangements by taking out all the warm and fuzzy stuff to leave you with an anxious, empty sound. He does let some color in on tracks like “& It was U” but overall stays distant. Never has a bad break-up (and crippling depression) sounded so smooth.

Burial – Kindred EP & Truant/Rough Sleeper

I have always described Burial as being on “another level” from other electronic producers and the two EPs released by William Bevan this year continue to prove me right. While eleven-minute electronic house opuses steeped in otherworldly distortion and dark ambiance may not be the most palatable thing in the world, it is good to see an artist unafraid to explore the world he chooses to create. While we wait for another jaw dropping album like 2007’s Untrue these two excellent EPS will just have to be enough.

Top 10

10. Four Tet – Pink

As any one who has spent a lot of time around me in the past year can tell you, I have been really into house music. In fact, much of this fascination was instigated by Four Tet’s fabulous Fabriclive mix from earlier this year. Many of the tracks off of Pink were released as singles or EPs, but they were really begging to be compiled. Four Tet (actual name, Kieran Hebden) is an electronic music veteran. He has put out six very different albums and more live mixes and song remixes than I care to imagine. Pink finds Hebden diving head first into the club. Where earlier records were rhythmically restrained in their minimalist tendencies, Pink lets the rhythm drive and builds the structure around those. Loops abound and bass pounds, but you never get the sense that Heben is leading you on aimlessly. This is music based in his roots, and you can tell he cares. This is really a great introduction to house music for someone with little to no experience, and rarely does a modern producer delve so deeply with no effort showing. Never has so much thought gone into music that encourages folks to stop thinking and just let go. You will dance my friends, oh yes, but you will do so consciously.

9. Alabama Shakes – Boys & Girls

I was a little skeptical of Alabama Shakes before I listened to them somewhere between the NPR accolades and adult-contemporary following. However, I allowed myself to indulge in this album. It is four-piece, grungy southern blues-rock in its purest form, nothing overly deep or onerous, and that is key. What really reaches through the speaker and grabs you is lead singer Brittany Howard’s primal howl. From the thumping “Hold On” to the trickling “Goin to the Party” to the love ballad of the year “You Ain’t Alone,” the consistency, believability, and sense of desperation of her vocals make up this album’s driving force. While there were other notable blues-rock releases this year, namely Jack White’s strong solo album Blunderbuss, nothing stuck in my mind so concretely as Boys & Girls. In this case, less is most definitely more.

8. Jessie Ware – Devotion

In a post-Adele world how does a young, female, British singer-songwriter make her work stand out? There probably isn’t one right answer to that question. But Jessie Ware certainly offers an intensely-appealing album of suggestions. Ms. Ware made her start singing hooks on electronic dance songs by the likes of SBTRKT and much of that club influence spills over into Devotion, her first solo work. However, despite the “of-the-moment” nature of the production Ware manages to expertly write and sing timeless love songs. The centerpiece ballad “Wildest Moments” is a song that could have gallivanted into glory by expressing the joys of a one-night stand or healthy sexual relationship. Instead, Ware manages to add uncertainty and poignancy by singing about a relationship that only makes sense to the two people involved. This attention and care makes an album that could easily have been just another pop-diva’s introduction into a collection of smart artistic choices and memorably intimate melodies.

7. Grizzly Bear – Shields

I’ll be up front: I love Grizzly Bear, always have. Ever since I heard those first tenuous notes of 2006’s Yellow House followed by the complete work-of-art that is 2008’s Veckatimest, Grizzly Bear has managed to run the emotional gauntlet from warm intimacy to cold distance. Shields finds the Brooklyn band venturing out into the wilderness to look beyond their own backyard for influence. Musical references range from jazz to The Beatles; somehow they manage do it all justice. The arrangements on this album conjure up landscapes as breathtaking as they are intimidating. You can feel that Shields came to be, relatively seamlessly and naturally when compared to the endlessly worked-over quality of earlier albums. In interviews, Grizzly Bear has said that this album was the most collaborative in terms of songwriting, and you can feel the vibe of a band intensely comfortable working together. In lesser hands, songs like these could easily be sappy or overly buttoned-up; in this case, it’s just What They Do. I’ll be damned if I can think of a band that does it better.

6. Beach House – Bloom

The most glaring critique I keep hearing about Beach House’s Bloom is that it “sounds too much like their earlier stuff.” While this is true, that fact is also precisely what makes Bloom such a strong effort. It has taken three other albums, but Victoria Legrand and Alex Scally finally take their synth-and-guitar-driven-dream-pop out of the bedroom and into the big wide world. The depth and scope of this album is impressive, as every song seems to, indeed, “bloom” from start to finish. Legrand’s voice is as scintillating as ever and the arrangements are indeed lush. However, her newfound lyrical assertions as well as the use of more confident percussion and rhythmic structures deepen and widen a sound that could easily peg a less-adept band into a corner. Beach House knows where their niche is and, instead of shying away from that, they have found a way to dive deeper into it. Bloom seems to say, in response to the criticism mentioned earlier, “Yeah it does and try to tell me you don’t love it anyway.” I can’t, and neither should you.

5. Grimes – Visions

Grimes is definitely a product of our over-digitized culture. Canadian art-student Claire Boucher makes music entirely on her laptop using technology that is, relatively speaking, available to anyone. She has garnered a following and buzz using just the Internet, no record label needed, and Visions is Boucher’s most accessible release to date. Despite being an indie darling (thank you Pitchfork), Boucher does something unexpected here by making something she clearly enjoys as opposed to trying to please critics or an audience (a tactic, I believe, more artists, in and out of music, should look into). You can tell she is having a lot of fun with this record. Her layering of her own sugar sweet vocals over gloppy, bounding digital tracks is equally appealing and subversive. The fact that you can hardly understand her lyrics (I’m pretty sure she slips into singing in Japanese on a couple tracks) is part of the escapist absurdity of it all. Visions is not the easiest album to listen to, to be fair. But it truly grows on you, going from ridiculous to danceable to contemplative in just a few minutes, further reflecting the over-stimulating effects of the Internet. By allowing yourself to revel in the commentary as well as the fun, Visions becomes a worthy indie-pop experience.

4. Kendrick Lamar – good kid, m.A.A.d city

good kid, m.A.A.d. city has already been hailed by some critics as, “the most important commercial rap album in the last decade.” So let’s calm down and start by jumping off the Kendrick Lamar bandwagon for a second. Yes, he is a skilled lyricist with a strong instinct for radio-friendly hooks. Yes, he expertly chooses assorted beats from the best of today’s hip-hop producers. Yes he’s been featured on every hot hip-hop track over the past six months. Yes, he can count such industry heavyweights as Lady Gaga and Dr. Dre in his corner. However, despite the buzz, what stands out most about Kendrick Lamar is his ambition. This album is subtitled a “Short Film” and indeed the scope of the narrative-driven LP can feel a bit cinematic at times. It contains twinges of naïveté, with stories of adolescent peer-pressure and family alcoholism (“Swimming Pools (Drank)”), mixed with youthful bravado (“Backseat Freestyle”), and a dash of timeless swagger (“Bitch, Don’t Kill My Vibe”). At the edge of it all gnaws the darkness and emptiness of growing up in South Central L.A. gang culture (or, for that matter, any violent American urban center) and the cultural contradictions often present in African-American culture, such as devotion to God and religion equal to that of substance abuse and violence. It remains to be seen where this album will fall historically; hence my tentative urging to give it some breathing room. It is, nevertheless, instantly recognizable as an important and original portrait of urban music in 2012 — and, by far, the strongest rap offering I have heard from a new artist in quite some time.

3. Frank Ocean – channel ORANGE

There is little doubt in my mind that Frank Ocean is the future of urban and pop-music. I am also decidedly OK with that. After an early mixtape in 2011, the phenomenal Nostalgia, ultra, and tabloid fodder regarding his sexuality, Ocean, whose birth name is Christopher Breaux, emerged from the hype with the meticulously-crafted channel Orange. The album is meant to transcend boundaries and identities, and it does. At first listen, it can come off as simply a strong debut from a pop singer. You can feel how much Ocean has sharpened his teeth while ghostwriting for such artists as Justin Bieber and John Legend. However, upon repeat listening, one can begin to recognize channel Orange as a much stronger statement; not just on Ocean’s pop sensibility but on America’s. The fact that a song as cloyingly sweet as “Thinkin’ Bout You” can slide into play on urban radio stations next to Rick Ross and Meek Mills, while still being a sing-along favorite for soccer moms, is both impressive and intelligent. This eclectic, constantly-shifting mix of pop ideas is so deftly, almost nonchalantly, executed that by the time you realize you’re listening to a John Mayer guitar solo over gloomy, ambient synths at the end of “Pyramids,” it’s almost too late. From start to finish, Frank Ocean plays to our comfort zone while periodically throwing in ideas you would not expect. A delight to listen to as well as to discern, channel Orange is an unexpected pop pleasure.

2. Flying Lotus – Until the Quiet Comes

This album represents a musical and intellectual quandary to many people. A traditionally hip-hop/electronic producer strips down his digital cacophony with (get this) live musicians. Steve Ellison (a.k.a. Flying Lotus) has embraced his heritage. He is the great nephew of Alice and John Coltrane. After releasing three albums to increasing critical acclaim he arrives with the wonderfully-understated Until the Quiet Comes. It is, in essence, an electronic jazz album. But before you write it off as overly experimental, just put it on and let it take you for a ride. The way in which Ellison can synthesize so many disparate elements (African percussion, free jazz, West Coast hip-hop etc.) into a cohesive sonic journey is a wonder to behold. The influence of fellow Brainfeeder Collective member, Thundercat is clearly discernable in the strong bass lines and psychedelic milieu. The use of live set musicians, as opposed to exclusively digital instrumentation, further expands Ellison’s current trajectory. Nothing here seems forced. And despite existing in a clear and heady intellectual space, there is something discernibly intimate and personal about this album. You really feel as though Ellison has found his “quiet” place where all his musical ideas can flow organically and take shape on their own.

1. Dirty Projectors – Swing Lo Magellan

For those of us keeping score at home Swing Lo Magellan represents Dave Longstreth’s eighth album in the past decade with his Dirty Projectors project. What is most impressive about the latest effort is the seeming lack of it. Longstreth finally seems comfortable in his own skin as a songwriter. Not to say he has abandoned his distinctly complex vocal harmonies or tempo shifts, but he has found a way to not let his technical arrangements get in the way of simple and pleasurable song writing. Swing Lo Magellan is a collection of literate love songs for a generation of young people hyper aware of the impending doom of society. However even in the darker moments of the album (such as “Offspring are Blank”), Longstreth trusts in his expressive and eclectic musicality to carry through while allowing himself to be lyrically playful. This is by far Dirty Projectors most accessible and fun release to date and it is undeniably catchy. Try getting the chorus from “About to Die” or “Impregnable Question” out your head after one listen…Impossible.

December 18th, 2012 — movie reviews

This is what I have instead of a Top-Ten (or Not Top-Ten): A handful of oddities that I’d wanted to bring up sooner rather than now. Chances are that, except for number two on this list, none of them will be in play during awards season. (And I’m already getting fed up with awards season even though it’s barely started.) So before this year ends (and it turned out to be a better overall year for movies than I thought it would be at midpoint, though still not as great as fifty years ago), here’s some surplus babble about stuff you’ve already forgotten about.

Moonrise Kingdom – Full disclosure: I was, as is the hero of this movie, 12-going-on-13-years old in the summer of 1965. I was so hopeless at making and keeping friends that I was bullied by boys even geekier than me. This may partly explain why I was drawn to this Wes Anderson movie more intimately than any of his others. I didn’t have an off-shore island at the edges of northern New England to escape to, except for whatever zone of solitude I was able to create for myself in the middle of southern New England. And I didn’t know then that what I really needed to deliver me from my pre-adolescent miseries was a gangly, brooding girl my own age with a violent temper, a yen for Benjamin Britten and a protective instinct towards fellow outcasts. It wouldn’t be the first time I’ve felt nostalgic for a past I never had. It is however the first time I’ve been genuinely touched by a Wes Anderson movie with real people (as opposed to the animated Fabulous Mr. Fox, which I also liked a lot despite the perpetually grandstanding, self-aggrandizing hero-figure all too typical of the Anderson c.v.) The guess here is that Anderson’s experience with making Mr. Fox helped tighten his narrative flow and keep his own gangly-ness under control. There’s a generosity-of-spirit towards his characters here that one associates more with Renoir or even Preston Sturges than with Wes Anderson; even the mean kids don’t seem so bad once you know them a little better. It doesn’t exactly make me want to go back to Rushmore or The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou for a visit. But I might give The Royal Tenenbaums or Darjeeling Limited another try after the New Year.

Beasts of the Southern Wild – This one still gives me trouble and I’ll try to keep the reason why as simple as I can: As much as I wanted – and waited – to be transported by this movie, I wasn’t. I keep wondering if this was my fault since Beasts has landed on the Top-Ten lists of critics I respect (and a few more of those I don’t). Yes I am as captivated as the rest of civilization by Quvenzhane Wallis and I believe Dwight Henry’s performance as her tormented, but ferociously loving father was itself a masterwork of empathy – and not bad at all for a man whose day job is baking. I also am all in with anybody’s efforts to coax magical realism from beneath the topsoil of American folklore using recent trauma (e.g. Katrina) and potential catastrophe (e,g. global warming) as psychic sources. But all the while I watching it, I felt as though I were willing the movie to become what it was trying to be instead of being drawn into its dreamy phantasmagoria. And just so you know, I hold no brief with those who find the movie in any way condescending towards its characters, especially when they’re as doughty as Wallis’ Hushpuppy or as complicated as Henry’s Wink. I suppose that even in a dreamland such as this, you can’t afford to find yourself drifting along for as many stretches as you do here. By the time the Aurochs finally got to the Bathtub, or vice-versa (go ask somebody else), I felt more detached from the dream than I should have been. The father and daughter were the only reasons I still cared. And that might have been enough in other movies. But not for one as ambitious as this.

Looper – Some of my friends, even those who claim to like science-fiction, contend there wasn’t much more to Rian Johnson’s thriller beyond a premise fitting more comfortably in an hour-long episode of The Outer Limits. I’d have watched such an episode several times over and I still wouldn’t have found the cunning verisimilitude Johnson sustains throughout this spirited chase through time. Ideas are what set off a science-fiction story. Plot is how you roll with it. But atmosphere, especially in an SF movie, is what keeps you staring at it. The way telepaths stuck at the bottom of the world off-handedly show off their kinetic skills, either from boredom or for drinks, makes you recognize a future you’re not sure will ever exist – or, on the other hand, doesn’t exist in some form right now. When an SF movie is really bad, there’s nothing worse. (Ask my old pals, Servo and Crow.) But when it’s as supple and smart as this, few things are better.

The Avengers –I have fonder memories of this comic-book movie than those of The Amazing Spider-Man (which had its own arcane charms) and The Dark Knight Rises (which had Marion Cotillard). Mostly, I just thought, pound for metallic pound, this had more antic energy being pumped into our collective foreheads. I also think it’s unfortunate that Mark Ruffalo’s shrewd, incisive performance as Bruce Banner, The Hulk’s alter-ego (or, to be more clinically accurate, super-ego), is destined to be overlooked for awards because of all the popcorn butter sticking to its surroundings. His quietly magnetic evocation of a lost intellectual struggling to contain his bone-deep fury stole the movie from all the buff physiques surrounding him. Somehow with all the other super-heroes and double-dealing villains looking either too anachronistic or too sleek, Ruffalo’s tweedy-but-wary reticence seems more above and beyond its immediate environment. He’s almost too good for the movie he’s in – and yet the movie would be even more disposable without him.

Robot and Frank – If Looper’s science-fictional premise seemed to skeptics custom-made for hour-long television, then Robot and Frank’s could fit into an installment of a half-hour series comprising unsold sitcom pilots. (I mean this as a compliment, because I grew up as a fan of those old summer anthologies — or of what Robert Klein once swept beneath the rubric, “Failure Theater.”) It’s a small, decorous movie that maybe needed to sublet some of Looper’s or, for that matter, The Avengers’ insurgent energy so it could leave deeper resonances. Frank Langella plugs up the more fallow aspects of this story with a beautifully enacted portrayal of a retired second-story man with creeping dementia who bonds with a talking appliance. You come away remembering him – and carrying at least one cutting irony: That an old man with an active grudge against a billionaire seeking to replace the printed page with all-digital texts uses artificial intelligence to carry out his vengeance. Those of us who roughly share a certain age might leave this movie wondering how much time we have left to pull off our own capers against a future we didn’t ask for – which constitutes as much heft as this lighter-than-air movie can take.

December 9th, 2012 — movie reviews

Flight (IMMEDIATE REACTION: By the way, who was that kid playing the cigarette-smoking cancer patient on the stairwell? Let’s see…James Badge Dell. He’s really, really good in this. Wonder if he’s as good with hair as without?)

Gene Siskel told anyone who brought up the matter that he believed Roger Ebert, his longtime TV tag-team partner, to have been a better writer than he was. That he was right only underscores how he may, by only a few millimeters, have been the better critic. I wish there were a published collection of his reviews that buttresses that contention. All I have instead are memories of his off-the-cuff insight on the old At the Movies programs. For instance, I remember when Siskel tossed into the broadcast his suggestion that if any contemporary movie actor was best suited to play James Bond, it was Denzel Washington. This seemed at the time (late eighties, I’m guessing) such a daring leap of imagination that one wasn’t sure it was allowed to ooze through a TV set. But not that daring since, by the first Bush administration, Denzel Washington had proven that he was cool enough to carry a movie, even if it wasn’t necessarily his movie to carry. (See Glory or, for that matter, Philadelphia, which he pilfered, fair and square, from Tom Hanks.) And much as I love defending Pierce Brosnan from undue criticism because it makes some white people I know very angry, the Bond franchise couldn’t have done any better or worse in the intervening years by taking Gene up on his modest proposal.

If anything, playing Bond would have held Washington back. He never needed anybody’s franchise to establish his own lucrative brand because he can not only carry a movie, he can open one – which was, as recently as the nineties, historically unheard-of for an actor-of-color who wasn’t named Bruce Lee or Sidney Poitier. Early in Washington’s career, I remember a colleague claiming that if anything held him back from being a major star, it was his innate sweetness; a quality she believed drew audiences in while making them incredulous that he could ever be totally malicious or crazed. I knew what she meant; Washington could keep you off-balance, but he never entirely scared you, not even in his Oscar-winning role as a deeply bent cop in Training Day. But keeping you off-balance is good enough to keep you interested without putting you off – a perfect formula for drawing total strangers to the nearest multiplex for repeat visits. What people expected from a Denzel Washington movie was a really competent guy (with an edgy, somewhat remote exterior) capable of handling highly combustible circumstances, saving a bunch of people — and, often in the process, teaching hard lessons to younger (usually white) people.

The pre-release trailers for Flight led audiences to believe they were getting the same thing; Denzel at the controls of a mortally-wounded airliner, barking out orders, seeming to have it all together, waking up apparently surviving, saving lives and…and…well, what’s all this about finding excessive alcohol in his bloodstream? Hey, it’s not a Denzel Washington movie without rough edges, right? Those trailers made it seem as though Washington’s character was being unjustly accused of something and hinted that somehow he would find a way to clear his name.

You don’t see those trailers anymore. Flight’s cover has been fully blown. Washington’s Whip Whitaker may be as supremely proficient as many of his archetypical roles. But that alcohol in his blood is not exactly a red herring and he most assuredly does not have it all together. Put plainly, Whip’s a sick bastard, a functioning alcoholic with razor-sharp instincts for both handling heavy machinery and denying his disease. The same cues of cool audacity audiences expect from a Washington performance are positioned here to make his character smaller, even wormier, than usual.

Which sounds like a gi-normous risk for a movie star of Washington’s stature to take. But Washington is that rare commodity: a big star and a great actor. He punches up Whip’s fighter-jock arrogance with a knowing swagger that leaves the scenery bereft of bite marks. But he also lets you see, in still moments, the puffy, baffled ruins of a proud man’s self-esteem. Watch Whip’s eyes as he faces two of the surviving crew members, imploring them to help him stay out of jail. “I really need this,” he tells chief flight attendant Margaret (Tamara Tunie) and he looks as needy and vulnerable as any lost junkie grubbing dollars for a boost. (He’s scarcely less feral at such moments than Kelly Reilly’s waif-ish addict Nicole.) Oddly, that innate sweetness mentioned earlier as a detriment to his star power remains within the audience’s reach as a safety valve for its sympathy. Deep down (all right, really deep down), there’s a happy little boy that used to love his life and his calling before his drinking hit the nightmare stage.

You wish the rest of Flight was as conscientious and adventuresome as Washington. The reviewers are correct in proclaiming it the best film Robert Zemeckis has directed since Cast Away back in 2000. But the movies in between, 2004’s The Polar Express and 2007’s Beowolf , were motion-capture experiments that never get past the point of being, at best, merely interesting And yes, that crash-landing makes for a damned harrowing set piece. But it’s not as though Zemeckis hasn’t made a plane crash before – even though in retrospect Cast Away’s disaster-at-sea emits the keep-hands-in-the-car-at-all-times aura of a sensory thrill ride. Flight’s central catastrophe, though its details are more scarily accessible to our nervous systems, has its own issues of razzle-dazzle to overcome – and, just maybe, some plausibility problems as well.

What bothers me most about the movie can be summed up with the depictions of the characters played by John Goodman and Bruce Greenwood. The latter’s portrayal of Whip’s old Navy buddy and union rep is fashioned with a quiet dignity and persuasive empathy while Goodman brings to Whip’s boyhood chum and dealer the leathery brio and seedy flamboyance of a Sons of Anarchy supporting player. They’re both fine at what they do, but just suppose the two characters had switched roles, but not temperaments? If Greenwood had been a quieter, more reasonable-seeming enabler of Whip’s self-destructive habits and Goodman a more antic, less circumspect defender of Whip’s civil liberties, the movie might have seemed less conspicuously a pure product of Hollywood and more like something that challenged expectations as decisively as Washington’s performance. (The minute Goodman, with dark-glasses and ponytail, sashays into view with “Sympathy for the Devil” pumping into his ear buds, you can barely keep yourself from yelling back, “We get it, OK? He’s fracking Satan! You don’t have to flash the semaphores and sirens!”)

This isn’t meant to denigrate anybody’s performances, least of all those of Goodman and Greenwood, both of whom I’m always delighted to see on the big screen. Everybody in the movie, in major and minor roles alike, is first-rate. It’s just that the movie’s overall vision can’t or won’t match Washington’s capacity to transfigure both his heroic aura and the addict-in-crisis subgenre Flight ultimately represents. Washington doesn’t just carry this movie. He is the movie. He’s the only reason you stumble out of the theater, blinking, groping and checking your own judgment for leakiness. It’s the crowning glory of everything he’s done thus far – and it’s too bad he wont get a third Academy Award for it, even though there was maybe a week after the movie’s release during which he was considered, more or less, a shoo-in. He’ll still get nominated (and after all, isn’t that what it’s all about?) But as much as I love Lincoln and its titular , titanic performance, Denzel Washington would have had my vote if I still had one to give at the New York Film Critics Circle. Gene Siskel, I like to think, would have understood why.

November 27th, 2012 — jazz reviews

So I’m finally catching up with Homeland after months of people yelling in my face about how my not being able to pay for Showtime was keeping me from a television series whose significance to our time-and-place rivals those of The Wire or The Sopranos. Even with all this hype and glory leading the way, nothing I’d read or heard before I dove into the DVDs alerted me to the relatively-minor-but-to-me-significant fact that Carrie Mathison, the ruthless, bipolar CIA counterterrorism operative played by Claire Danes, is a serious jazz buff.

At first, I’m thinking: How great for jazz to have even this much ancillary presence in a prestigious pop-culture phenomenon. And then I think, well, yeah, but…she’s, like, clinical, man! And not always in a good way. Do the producers imply that jazz is part of her problem, or a plausible way out of her personal wilderness? Hard to tell so far, except maybe for a crucial clue she derives early in the first season from watching a bass player’s fingers work through a chord progression. These days, serious jazz buffs, with or without their maladies showing, will take whatever they can get in validation from the zeitgeist.

Somehow, jazz goes on, with or without pop validation – even, as one keeps hearing, without compact discs, though one also hears of something called “vinyl” making inroads in the marketplace. One is still haunted by the passage of time – and of those who helped write the history of jazz’s first century. One of my picks is led by a man who died in 2011, and most of the albums listed here pay homage to another, bassist Paul Motian, paragon and patron saint of progressive music, who mentored or inspired many of the musicians cited below Nevertheless, those who follow Motian’s example aren’t standing still, but moving ahead, heedless of what the aforementioned marketplace is thinking about – when, that is, it bothers to think at all.

1.) Ron Miles, Quiver (Enja/yellowbird) – This intricately-wired gadget had me at hello with “Bruise” – which, at least to these ears, compresses the wavering emotional trajectory of one’s average 24-hour existence into nine-and-a-half action-packed minutes. And, as with any album worth its ranking, it just gets better from there. You wouldn’t think you’d get a big, thick sound out of a trio comprising a trumpet (Miles), a guitar (Bill Frisell) and a trap set (Brian Blade). But this isn’t your average chamber-jazz aggregation. It’s a pocket-sized orchestra with Frisell in top form, whether laying down chords broad enough to encircle a botanic garden or spinning contrapuntal phrases that make antsy-little-bird patterns in the sky. Blade’s already established himself as the most audacious of his generation of drummers and he proves here that his ears are as big as his moxie. Miles, one of the versatile and underappreciated horn players of the present day, leads the way with a nerviness too assured to put on airs, but not afraid to think while singing – or vice-versa. Everything this trio touches works like a fine old timepiece, whether it’s Cotton-Club Ellingtonia (“Doin’ the Voom Voom”), gut-bucket blues (“There Aint No Sweet Man that’s Worth the Salt of my Tears” – and who needs a lyric sheet after a title like that?), old-school balladry (a back-door approach to “Days of Wine and Roses”) and even some rockabilly-with-quirk-sauce (“Just Married”). After you’re through listening to it, wind it up again just to see how the tunes land in your head a second or third time. And that won’t be enough.

1.) Ron Miles, Quiver (Enja/yellowbird) – This intricately-wired gadget had me at hello with “Bruise” – which, at least to these ears, compresses the wavering emotional trajectory of one’s average 24-hour existence into nine-and-a-half action-packed minutes. And, as with any album worth its ranking, it just gets better from there. You wouldn’t think you’d get a big, thick sound out of a trio comprising a trumpet (Miles), a guitar (Bill Frisell) and a trap set (Brian Blade). But this isn’t your average chamber-jazz aggregation. It’s a pocket-sized orchestra with Frisell in top form, whether laying down chords broad enough to encircle a botanic garden or spinning contrapuntal phrases that make antsy-little-bird patterns in the sky. Blade’s already established himself as the most audacious of his generation of drummers and he proves here that his ears are as big as his moxie. Miles, one of the versatile and underappreciated horn players of the present day, leads the way with a nerviness too assured to put on airs, but not afraid to think while singing – or vice-versa. Everything this trio touches works like a fine old timepiece, whether it’s Cotton-Club Ellingtonia (“Doin’ the Voom Voom”), gut-bucket blues (“There Aint No Sweet Man that’s Worth the Salt of my Tears” – and who needs a lyric sheet after a title like that?), old-school balladry (a back-door approach to “Days of Wine and Roses”) and even some rockabilly-with-quirk-sauce (“Just Married”). After you’re through listening to it, wind it up again just to see how the tunes land in your head a second or third time. And that won’t be enough.

2.) Ravi Coltrane, Spirit Fiction (Blue Note) – After more than a decade in which Ravi Coltrane’s been out-front as a leader and composer, newcomers still insist on bringing his parents into the discussion; how he and John play the same axes, how much they’re alike (or not), how Alice’s incantatory style has influenced him and on and on…No use complaining, since just about everything’s that been said on these matters so far has been true. But as of this, his most accomplished album yet, Coltrane has more than earned the right to have his artwork taken on its own distinctive terms. Enabled by co-producer Joe Lovano (about whom, more later), Coltrane triumphantly puts forth a personal vision that inquires as lithely as it asserts, that probes as decisively as it propels. He and his album benefit from having two ensembles at their disposal; a quartet with pianist Luis Perdomo, bassist Drew Gress and drummer E.J. Strickland that gives added running room for Coltrane’s massive chops (especially on such freewheeling runs as “Spring & Hudson” and the more meditative showcase for his soprano sax, “Marilyn & Tammy”) and a quintet with trumpeter Ralph Alessi, bassist James Genus, pianist Geri Allen and drummer Eric Harland that engages his conversational agility. And with individualists as those in the latter crew, one can’t help but listen as deeply as one speaks. Alessi’s compositions, “Klepto,” “Who Wants Ice Cream” and “Yellow Cat,” extract deep tone colors and slippery phrasing from Coltrane as the imperturbable Allen strings together gem-like chords with escalating force. Lovano joins in on worthwhile examinations of Ornette Coleman (“Check Out Time”) and the aforementioned late, lamented Motian (“Fantasm”).

2.) Ravi Coltrane, Spirit Fiction (Blue Note) – After more than a decade in which Ravi Coltrane’s been out-front as a leader and composer, newcomers still insist on bringing his parents into the discussion; how he and John play the same axes, how much they’re alike (or not), how Alice’s incantatory style has influenced him and on and on…No use complaining, since just about everything’s that been said on these matters so far has been true. But as of this, his most accomplished album yet, Coltrane has more than earned the right to have his artwork taken on its own distinctive terms. Enabled by co-producer Joe Lovano (about whom, more later), Coltrane triumphantly puts forth a personal vision that inquires as lithely as it asserts, that probes as decisively as it propels. He and his album benefit from having two ensembles at their disposal; a quartet with pianist Luis Perdomo, bassist Drew Gress and drummer E.J. Strickland that gives added running room for Coltrane’s massive chops (especially on such freewheeling runs as “Spring & Hudson” and the more meditative showcase for his soprano sax, “Marilyn & Tammy”) and a quintet with trumpeter Ralph Alessi, bassist James Genus, pianist Geri Allen and drummer Eric Harland that engages his conversational agility. And with individualists as those in the latter crew, one can’t help but listen as deeply as one speaks. Alessi’s compositions, “Klepto,” “Who Wants Ice Cream” and “Yellow Cat,” extract deep tone colors and slippery phrasing from Coltrane as the imperturbable Allen strings together gem-like chords with escalating force. Lovano joins in on worthwhile examinations of Ornette Coleman (“Check Out Time”) and the aforementioned late, lamented Motian (“Fantasm”).

3.) Vijay Iyer Trio, Accelerando (ACT) – There’s no respite in pianist Iyer’s assault on the traditional jazz repertoire. If anything, his trio shakes things up with even more urgency on its latest production. Yet there’s also greater authority in its overall execution given how better attuned its members are to each other’s instincts. With something as well-worn as “Human Nature” (and no, once and for all, Michael Jackson did NOT write it, but my Hartford housing-project homeboy Steve Porcaro did with John Bettis), Iyer, bassist Stephen Crump and drummer Marcus Gilmore re-jigger familiar elements into something like a grand incantation while still making it sound like something you could dance to (though it might be a slightly different dance from the one you’re prepared for). The trio also unearths unexpected theme-extending possibilities in other pop-funk guests on the playlist: “Mmmhmm” by bassist “Thundercat” Bruner and Flying Lotus and “The Star of the Story”, written by Rod Temperton for the seventies disco band Heatwave. The jazz “standards” are, of course, so left-field that Henry Threadgill’s wildly-eccentric “Little Pocket-Sized Demons” is given as straightforward a reading as can be imagined while a conventionally-swinging foundation is generously applied to Herbie Nichols’ typically-unconventional “Wildflower.” And why doesn’t it surprise that when Duke Ellington is invited to the party, his house gift is the lesser-known-than-it-should-be “Village of the Virgins,” from the maestro’s collaboration with choreographer Alvin Ailey? Iyer’s own pieces, including the explosive title track, move forward with a kind of mutant turbulence reminiscent of both Andrew Hill and Charles Mingus, while achieving a definitive shape they’ve earned on their own. It’s hard to tell at times whether harmonies are being re-imagined here as rhythms, or the other way around. Either way, you’re ready for whatever the Iyer Gang stirs up next time.