July 10th, 2013 — movie reviews

IMMEDIATE REACTION: What does it mean that while only 26 percent of critics on Rotten Tomatoes’ scale approved of this movie, 68 percent of audiences have so far liked what they saw? Probably nothing. Maybe everything.

It’s way too long – as are so many big-studio blockbusters intent on showing every single dollar spent on screen. It’s at times a tad too pleased with itself, especially in the way it blatantly samples from so many other (better) movies from Little Big Man to The General (lots and lots from The General, in fact, given all those intersecting locomotives) to the collected works of Sergio Leone, Steven Spielberg and even its own director Gore Verbinski. And while it’s far more respectful towards indigenous Americans than you might believe, you still wonder why they all…well, I wouldn’t want to give too much away even if you have no intention whatsoever of seeing The Lone Ranger. And a lot of you don’t, I’m sure, based on its overwhelmingly negative reviews and its underwhelming box-office results thus far.

That bad odor followed me into a bargain matinee of Lone Ranger this week. I couldn’t help it, being of a certain age wherein I cut my teeth on the 1950s Clayton Moore-Jay Silverheels TV series, devoured the legend’s crudely captivating mid-1960s animated TV version and was as recently as a year ago pulling people’s coats about Brett Matthews and Sergio Cariello’s controversial graphic (in every sense of the word) novel which steeped the creaky old mythos in oily western noir. I had to see for myself how bad the movie was and as I watched, I kept waiting for it to start getting as irredeemably awful as everybody warned me it would. It never happened.

In fact, for all of its problems, The Lone Ranger turns out to be a buoyant, insouciantly subversive ragbag epic. As only a few others besides me have noted, even the aforementioned samples from other movies contribute to Lone Ranger’s fun-house distortions of both frontier mythology and popular culture. Yes, it conspicuously takes on the trappings of a gimmicky action blockbuster with a campy Johnny Depp star turn jury-rigged to draw in those who unconditionally loved the last couple of gimmicky action blockbusters with a campy Johnny Depp star turn. But the movie subjects its own motives and methods to constant scrutiny and, in hit-and-miss fashion, weaves this self-awareness into the narrative with goofball nonchalance. It’s every bit the arch, intricately designed feature-length cartoon that the Verbinski-Depp collaboration, Ringo (2011) was, only with more flesh, blood and gore, so to speak. If this version had come out back in 1981, instead of that misbegotten, deservedly forgotten The Legend of the Lone Ranger, it might have been seen as a genre-transforming breakthrough. Now, it’s just a big fat Hollywood summer movie that seemed destined for cautionary-tale status even before it opened.

I wonder why. Just about every summer preview I’d seen this past spring seemed to be spraying Lone Ranger with bad juju. And, as always, the pundits were more concerned with the packaging than with whatever was inside the box. Why, they wondered, dredge up an eighty-something-year-old radio serial that no one under 50 (maybe, more like 55) knows or cares about? The fact that Disney brought back the “team” that gave a grateful world the Pirates of the Caribbean trilogy – which, to this viewer, was at least a movie-and-a-half more than the world needed – seemed to some more like a cynical money-grubbing gesture than a calculated gamble; as if the Giant Mouse was desperately reaching back to “those thrilling days of yesteryear” for its theme parks’ Next Big Thing (though, having seen the movie, I’m damned if I can figure out what thrill ride the company’s going to get out of this one.)

There was also an undercurrent of Depp Fatigue in these advance warnings. In this age of gnat-wing attention spans, the air was buzzing with whispers that Johnny Depp’s high-concept dress-ups were getting thin and (more to the point) less lucrative. Last year’s Dark Shadows applied a coup de grace to the idea of Depp’s outrageousness carrying a movie along. His Barnaby Collins was a blissfully, sometimes poignantly realized reboot. But you kept waiting in vain for the rest of the movie to get better – or get moving. So one imagines the long knives were unsheathed for this Depp turn, especially since he had the cheek to assume the role of Tonto, the title character’s Native American companion. Geez, why not the Lone Ranger? After all, he’s…you know…and you’re…like…and Tonto…He’s…Oh jeez, this is SO awkward….

I’m not going to spend too much time and space here unpacking this issue in all its historical and cultural permutations – and don’t you start with me either. But in the first place, why in the name of John Reid WOULD Depp choose to play the Lone Ranger? Even in the graphic novel, Reid is a decent, dashing fellow who, despite his patrician polish and random knowledge of small firearms, science and anatomy, is the biggest cube in the icebox. Arnie Hammer’s been taking knocks for being a bland, toothy cipher. But that’s what the Masked Man essentially is – and also what Verbinski’s movie chooses to emphasize. Hammer’s just fine in the role; though he does at times betray a level of embarrassment with the hissy fits the movie requires him to toss, especially at Depp’s Tonto, whose reinvention here as both sham and shaman, as trickster and bumbler, as sleazy sidekick and alpha dog, should be lauded rather than castigated. It’s certainly an improvement over the kind of routine abuse Bill Cosby once cited in the second all-time best Lone Ranger shtick by a stand-up comic. (This, of course, is the first.)

And sure, it would have been wonderful for Disney and company to seek out a Native American actor who could bring to this Tonto the kind of comedic timing, deadpan agility and glam-rock swagger that made Depp a star. But we don’t live in that world now. (We should, but we never did and likely won’t in the foreseeable future because trees are smarter, braver and more imaginative than most of the bean counters running the movie industry these days.) As he did with Barnaby Collins and, to a lesser extent, with Willy Wonka, Depp inhabits not just a pop-culture figment of somebody else’s imagination, but our own tangled presumptions about that character to the point where he can upend, shatter and remake those presumptions to his own eccentric specifications. Put another way, it’s hard to think of Depp’s Tonto as red or white (not even with that threadbare makeup cracking and peeling before our eyes.) He’s the stone-faced imp in our collective memory bank, rewiring a hallowed, if anachronistic pop myth so emphatically that even that Kemosabe cube has to rethink his heretofore tidy value system. Also, how can anyone say this Lone Ranger maintains the hierarchical status quo when just about every one of its pale male characters, especially its eponymous hero-savant, comes across as some variant of a “stupid white man”?

This won’t mitigate the carping and it shouldn’t. Just like it shouldn’t have taken 145 minutes to make an entertaining western adventure-spoof. (Blazing Saddles clocks in at 93 minutes; even The Mask of Zorro managed to maintain a brisk, eye-filling pace at 136 minutes, complete with set pieces.) Half the plot strands, even the slingshot-wielding kid who is maybe the Green Hornet’s grandfather, could have been dispensed with. But more not less is, as noted, the profile Hollywood insists upon for action movies. Verbinski’s movie can’t help but resemble a mammoth popcorn spectacle given the global market demands. The real fatigue Lone Ranger represents isn’t with Johnny Depp or even with westerns, though this movie’s perceived failure may have further pushed back the genre’s dim prospects for resuscitation. It’s with the hidebound hot-air chatter over summer tent-poles and trillion-dollar spectacles. If the two guys most responsible for initiating this era of movies now foresee its demise, then the timing for Lone Ranger Redux is even worse. This version should have been made at least thirty years sooner. It could be another twenty years before we can say for sure whether it’s bad or good.

June 19th, 2013 — jazz reviews

My live-music drought ended last week as I attended a couple of club dates associated with the DC Jazz Festival. I saw Cyrus Chestnut at the Hamilton and couldn’t decide whether I was more astonished at how much better he’s gotten at this piano-trio thing or that he’s now months shy of his 50th birthday. (Watching him be clever, engaging and soulful at the same time makes me think he not only compensates for Mulgrew Miller’s absence, but Dave Brubeck’s, too.) I also made my long-overdue first trip to the Bohemian Caverns on U Street to hear the seemingly unstoppable Pharaoh Sanders lead his secular-spiritual congregation in song. (His tenor doesn’t have a fastball any more, but it can still pull a high, hard one out of thin air when he needs it.)

But the best jazz performance I saw this past week wasn’t affiliated with the festival. It was Saturday night at Wolf Trap as Dr. William Henry Cosby Jr. had the Filene Center stage all to himself, sharing it with no one but a pair of sign-language specialists trading off translation duty for the whole two-and-a-half-hours-with-no-intermission-whatsoever show. He spent the whole time talking, just talking…in roughly the same manner that Ben Webster or Pee Wee Russell were just groping for notes on their respective instruments.

Now before I go on…

It’s become a conditioned reflex, especially on the Internet, to acknowledge anything with the words, “Bill Cosby”, as a prelude to (or occasion for) sanctimony or indignation. He has, within the last decade, gone from being an ecumenically beloved entertainer to a polarizing figure, especially within the African American community, whose adults he has challenged or chastised, depending on how you hear him submit his case, to take greater responsibility for their children’s well-being and education. Some believe he speaks the truth that few want to hear while others think he speaks with the haughty arrogance of the wealthy. Then again, even if he hadn’t brought all this up, people will still say he’s haughty and arrogant only because he IS wealthy. Take your pick, brothers and sisters: A passionate “race man” using his power and fame to staunch long-festering socio-cultural wounds with astringent medicine or just another plutocrat playing his own version of that venerable board game, “Blame the Victim.”

I say, with a clear conscience: Whatever. I’ve heard and, at times, even said some of the same things Cosby has about community responsibility — and been resoundingly, unanimously ignored for my trouble. On the other hand, if the Michael Eric Dysons of the world want to rip Cosby a new one, it’s no skin off my ass nose. I don’t have an investment in Bill Cosby the public scourge, philanthropist, educator and TV icon. I am, however, quite weary of the way all these other classifications further diminish or obscure the enduring artistry of a master storyteller adjusting his craft to the pressing demands of age and time.

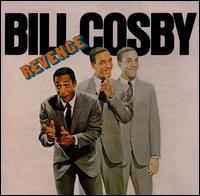

After all, just about everything I’ve ever learned about narrative development didn’t begin with my reading Dickens or Chekhov or even Garcia Marquez. It began with my exposure to Cosby’s LPs of the 1960s. If all you remember of the first “Fat Albert” story from the 1967 LP, Revenge, is that damned “Hey-Hey-Hey!”, then you’re part of this problem. What I remember is that part of the track where Cosby’s recalling the time he tried to get a rise out of Albert by pushing, shoving and jamming him up several flights of stairs leading to a dimly-lit, horror-movie cut-out of a monster. All the while, the younger Cosby’s anticipating the hilarity that will ensue when jovial Albert is frightened out of his wits. The build-up climaxes with the appearance of the scarifying cutout, punctuated by this sound: “AAARRRRAAAUWWGH” (or something to that effect).

Then there’s a pause, not long, but spacious enough to allow Cosby to say, as blankly and blandly as possible: “I forgot I was behind him.” The sentence stands there, suspended in mid-air. Forty-plus years later, I’m still trying to write something as immaculately framed and timed as that.

Watching Cosby work at Wolf Trap (and he’s been touring with most of this material for some time now), I’m aware that, at 75, his build-ups and pay-offs don’t have that same giddyap they did when he was the 28-year-old phenom able to connect his North Philadelphia childhood memories with the world-at-large either through the telling little detail (“idiot mittens”) or the plausibly implausible exaggeration (“Nine-hundred cop cars!”) And yet, paraphrasing his late friend Dizzy Gillespie, Cosby has benefited from a lifetime’s experience in learning what NOT to say and when NOT to say it. So he now uses bigger frames and larger spaces, letting them do more of the work than the words. Most comedians (and musicians) temper their deliveries, slow their rolls as they age without showing any lapses in their command of time and space. And Cosby, a far more formidable rhythm master as a public speaker than as an actual drummer (by his own admission), can make an evening zoom by while seeming to amble along in measured, deliberate steps. How he’s managed to fill amphitheaters with this slow-hand delivery in the digital age is both a major mystery and a minor miracle.

I’d heard the centerpiece story before: An epic ramble about his eldest daughter’s misadventures with higher education – though I suspect he has by now conflated the experiences with other offspring. He braided this version with other, comparably familiar narrative strands. For instance, how a girlfriend, with the emphasis on the last syllable, changes everything, including the balance of domestic power, upon becoming a spouse. (Yes, Camille comes in for yet more ridicule, but something tells me she enables this treatment — up to what point I suppose we’ll never really know.) Then there are the vagaries of being rich and influential. (Upon asking the president of a college to which his daughter seeks admission whether he could use a hospital, the president asks, “And just how bad were those SAT scores, Mr. Cosby?”) He’s gotten cuffed over the last thirty years for leaning on this persona, to which one can only say that he has as much right, even a duty, to mine material from his rich-and-influential life. He was the lovable curmudgeon throughout, yet the evening was generally sanctimony-free – unless you count his rendering of a college graduation in which the top two students of the class, both foreign-born, accepted their diplomas with circumspection and restraint, while the relative underachievers went into ever-more-elaborate variations of the end-zone celebration. Grouchy or not, the displays made their point, each marking one of the precious few times he got up from his chair.

I’ve read elsewhere that 90 minutes is usually his limit. But the fact that he went over his anticipated two-hour time allotment suggests he was enjoying himself. And maybe these concerts are now his down time from being pressed for commentary about families and education. There are worse ways to blow off steam than frolicking with sound the way a painter plays with light. Hardly anyone thinks of Bill Cosby in such aesthetic terms. And it may be partly his fault that more people don’t. But they should.

June 16th, 2013 — movie reviews

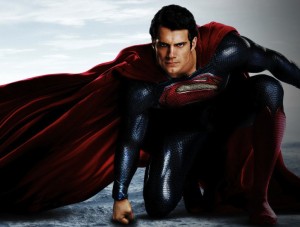

This really shouldn’t have surprised anybody. I’ll go out on a very slender limb and predict that the 71 percent drop for Man of Steel will be even more precipitous over the next few weekends. Summer blockbusters eat each other like the savage carnivores they are and it’s more than probable that by Bastille Day (or, maybe, the Fourth), Clark Kent will join Tony Stark and Mister Spock at the rickety refuse-truck stop on the outskirts of Hype City wondering where the buzz went. The latter two shouldn’t worry too much about coming back. But Superman? He’s in a vulnerable spot. The last time they tried to retrofit him into a new movie franchise, they did it with a movie with an impressive cast, a generally favorable critical consensus (though hardly an overpowering one) and the requisite big-bang set pieces. But for whatever reason, Superman Returns (2006) collected a indecipherable odor that kept it from re-igniting the franchise. In retrospect, Hollywoodland, the neo-noir biopic probing the mysterious death of George Reeves, was the Superman movie that more people talked about that same year. Maybe because it had a better lead actor? You be the judge. I think it may have had something to do with where the world now places its collective memory of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s 75-year-old creation…and whether it believes it can now do without the myth of Krypton’s Last Son.

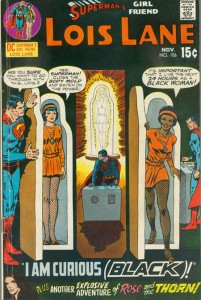

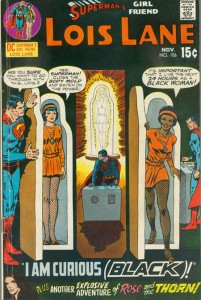

Some of this tangled feeling poked through many of the reviews for Man of Steel (a less impressive consensus this time around, but deceptively so) which moped about Zach Snyder’s reboot having few of the “fun” trappings of Superman’s earlier TV and movie incarnations. These pundits lamented what they saw as the heavy hand of producer Christopher Nolan imposing upon their Superman (whoever that may be) the kind of murky shadows and psychological depth that informed his Dark Knight trilogy’s re-framing of Batman. I found most of these complaints inane and ill-informed. Anybody who grew up reading DC comics at any point in the last 50 or even 60 years knows that there is not now and never has been a life story of Superman that wasn’t subject to revision or tweaking short of making him a refugee from somewhere other than Krypton who landed somewhere other than Kansas.. (Remember all those “what-if” issues of the late 1950s and early 1960s? “What If Lex Luthor Was Superman’s Friend?”, “What If Superman’s Real Parents Came to Earth With Him?” and my all-time favorite, “What If Lois Lane Were Black?” You can look that one up yourself.) For what it’s worth, I always preferred the animated versions of Superman above those with Reeves and even Reeve. Look here and here….and, what the hell, even here.

Ah, yes, that reminds me…Remember the first “teaser” trailers they were showing for Man of Steel, the ones that started running sometime during last summer’s political conventions? They were a gauzy montage of images; a butterfly on a swing, some farmland shrouded in morning fog, a fishing boat with grimy bearded men, a little boy playing with his dog amidst backyard clotheslines with some big red towel or blanket trailing behind him…

At the time, I thought: “Smallville Mon Amour”? I’d be up for that. I figured if Nolan, Snyder and screenwriter David S. Goyer were REALLY serious about dialing everything down to zero and rebuilding the myth from there, they could do a lot worse than take things sideways and make it a more intimate and, thus, more daring species of superhero movie. Sure, you would have bewildered more mass circulation critics, spooked the global distributors and angered the carny rabble. You might even risk flopping worse than, say, Breakfast of Champions or Gigli. Good or bad, you wouldn’t have left anyone indifferent. And what’s more: People would have been talking about your movie beyond opening weekend and (maybe) kept the buzz going all summer long.

As it is, Snyder’s reboot manages to broaden the myth’s expressive possibilities while fulfilling the corporate mandate of blowing things up, literally and figuratively speaking. (More on this later.) Up till now, the romance of being Faster Than…, More Powerful Than…, Able to Leap…, etc. emitted such a powerful hold on our imaginations, at whatever age, that it rarely , if ever, occurred to us to ask what should have been the myth’s most pressing question: How do you adjust to life among other humans if you’re so drastically, even cosmically different from everybody else? A lot of us ran to comic books looking for heroes who were empowered, rather than diminished by being different. What’s best about Man of Steel is its willingness to drink deep from that dilemma. I loved the whole subplot about Clark (and, later, the other Krypton survivors) reeling from the sensory overload caused by being able to see through and hear everything around them. It’s the last thing the lazier savants want to hear: that being super is just another way of being seriously fucked.

There was one moment that chilled me more than anything else in Man of Steel or any other superhero movie in recent memory. It came when Kevin Costner, in his most striking big-screen performance in decades as Jonathan Kent, is reminding his adopted son to resist disclosing his powers, even if they were needed to save his schoolmates from drowning in a waterlogged school bus. “Should I have let them die?” Clark asks. A pause from Pa seems to last forever before he finally mutters, “Maybe.” There’s a web of weary, conflicted emotion enveloping that reply and if the rest of Man of Steel managed to modulate its gaudier impulses in the same manner as Clark struggled to rein in his hearing, it might have been something major, instead of…just big…

…and loud…and messy…I mean I hate being predictable, but count me among the wet blankets who left the theaters grousing about the ringing in their ears and metal shavings in their mouths from all the concussive property damage, the bloodless (and thus, ultimately, numbing) carnage and the multiple rounds of false climaxes that are supposed to let everybody know how much Warner Bros. has spent to keep you distracted. (At least that last Dark Knight movie tried to be clever with its post-traumatic red herrings.) I think I also agree with this writer that there was something especially unnerving about the last of its climaxes — and not in a good or even terribly imaginative way; while I can’t believe I’m still not trying to spoil anything at this point, that climax also looked as if the movie makers were trying to extricate themselves (literally) from a corner & copped out with the least fuss possible.

To sum up: Rather than open new ways to expand or interrogate the Superman myth, this movie turns him into just another action hero who, though he may indeed be hotter than any other (at this point, the only thing people keep talking about after the show’s over is Henry Cavill’s off-the-charts eye-candy quotient) doesn’t exactly make you curious to see where he goes next. And maybe that’s the movie’s biggest problem. But it may also be a problem with our first true superhero, the template upon which all others have been fashioned. The novelty of seeing a man fly faster than sound has worn off, though we’ll never get tired of seeing him surprise others with his feats of strength. (Those vignettes of Clark wandering from one grimy outpost to another, leaving shock and awe in his wake, make up what genuine charm the movie carries.) However Man of Steel ultimately fares in the marketplace, I don’t think they’ll leave the story hanging this time. But rather than whatever the movie’s detractors claim to miss in wit and charm, I’d settle for the simple pleasures of the unexpected next time around.

For instance — and this is in no way a knock on Amy Adams, to whom I remain avidly (avidly) devoted — but, I mean, what about…I mean…why not:

As I said, a sense of wonder….

June 12th, 2013 — jazz reviews

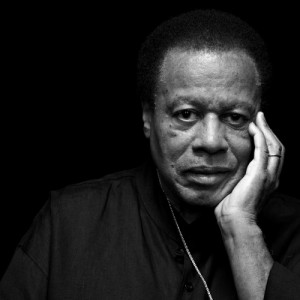

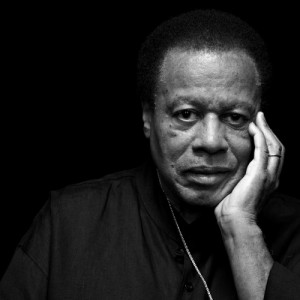

1.) During the one time I interviewed Wayne Shorter, I asked why no one had ever asked him to compose a film score. This set him off on an epic soliloquy on how male movie stars walk from Bogart, Gable and Cagney to Lancaster, McQueen and (I think) Poitier. He got up out of his chair and gave brief, impromptu imitations. He even brought Kirk Douglas into the discussion by which time he got me so caught up in whatever he was saying that I tried to bring such contemporary-cool avatars as Douglas’s son Michael and Denzel Washington into the mix (to little avail). He digressed into matters of posture, pace and the way people sway their arms in stride. It was enrapturing, frenzied and elliptical; like much of his music, only with words. I didn’t, couldn’t write any of it down because I knew I’d never get it in my paper. I wish I could find the tape, though. I also wish he’d answered my original question – and still wish that that somebody, anybody else would, too.

1.) During the one time I interviewed Wayne Shorter, I asked why no one had ever asked him to compose a film score. This set him off on an epic soliloquy on how male movie stars walk from Bogart, Gable and Cagney to Lancaster, McQueen and (I think) Poitier. He got up out of his chair and gave brief, impromptu imitations. He even brought Kirk Douglas into the discussion by which time he got me so caught up in whatever he was saying that I tried to bring such contemporary-cool avatars as Douglas’s son Michael and Denzel Washington into the mix (to little avail). He digressed into matters of posture, pace and the way people sway their arms in stride. It was enrapturing, frenzied and elliptical; like much of his music, only with words. I didn’t, couldn’t write any of it down because I knew I’d never get it in my paper. I wish I could find the tape, though. I also wish he’d answered my original question – and still wish that that somebody, anybody else would, too.

2.) In the summer of 2001, he appeared – materialized? – at New York’s JVC Jazz Festival in one of the first live appearances of the quartet that many now consider the best small combo in jazz. (This is by no means a unanimous opinion; more later about this.) So much time had passed since people heard him playing acoustic jazz with a rhythm section that there were several red-zone levels of anticipation for this show, the closing act of a three-tiered bill that, if memory served, included a crowd-pleasing Chick Corea set. The house fell in on him as soon as he walked on-stage. But the glow receded as soon as he started playing. He seemed reticent, even tentative, as if he were still hugging corners of the shadow-world in which he’d embedded himself for most of the previous decade. It wasn’t quite the rouser everyone in Avery Fisher Hall was amped for and one remembers how deflated even the most indulgent true believers looked as they filed out that night — though, to be fair, that acoustically-challenged venue may not have been the most ideal for a quartet seeking a détente between rumination and momentum.

3.) On the other hand, what else DID they expect? A John Coltrane-style secular-mystical revival, radiant fire breathing and all? That’s not what you anticipate – or even desire – from Wayne Shorter, though he’s certainly proven himself capable of such incantatory drive. (I don’t know how many times I’ve played Juju among friends and found those unfamiliar with the album swear that it was Coltrane playing that tenor, even after I’ve told them otherwise.) Shorter, going all the way back to his mid-1960s tenure with Miles Davis (and more so with his Blue Note albums of that period) always connected with the writer within me. He had a distinctive, near-oblique narrative voice: lyrical, inquisitive, restless, but always with a solid harmonic foundation bracing his often-eccentric digressions. The sound of his saxophone didn’t swallow you whole as Coltrane’s could, but rather carried you along like a magical-realist storyteller. As with the best music of that era, Shorter’s playing and composing didn’t impose their mystique upon you so much as invite you to come up with your own poetic responses. George Harrison would have understood where Shorter was coming from – and for all I know, likely did.

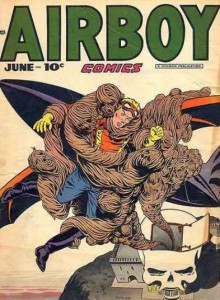

4.) I just now remembered something else from that interview: His abiding interest in comic books and in one series in particular featuring a dauntless young aviator named “Airboy.” (There was one other hero whose name now escapes me. I’ve GOT to find that tape!) It occurred to me at that moment to ask why he never wrote a tune with “Airboy” as a title, but somehow we got caught up on another subject.

5.) As for writing a score for movies….what the hell. The way Hollywood is now, he’d be a lot better for them than they’d be to him. Best to make up your own movies in your head while listening to “Chief Crazy Horse” or “Mah-Jong” or “Schizophrenia” or “Over Shadow Hill Way” or “Calm” or “Face of the Deep” or “Deluge” or “The All-Seeing Eye” and…Know what? Even some of the titles, when you throw them in the air come across like some allusive, inscrutable and faintly volatile Shorter solo when they hit the page.

6.) So then…what about the other guys – Danilo Perez on piano, John Patitucci on bass and Brian Blade on drums? Do they and their leader deserve to be mentioned in the same breath as the Davis-Shorter-Hancock-Carter-Williams tandem – or any other classic small-jazz group that you can think of? Maybe it’s enough that Shorter always looks on-stage as if he’s overjoyed to be with them. I always had the feeling that from the start of their association, each member of the rhythm section was using his own resources to draw Shorter further out into the open. If their latest album, the aptly titled Without a Net (Blue Note) is any indication, they’re still tugging, coaxing and, especially in Blade’s case, shoving Shorter towards the deeper end of the pool. Often, it sounds as though he’s hanging back at the start, letting his fellas set the table before allowing whatever’s in his head seep or leap into view. Hence his off-the-cuff rendering of the “Lester Leaps In” theme that opens “S.S. Golden Mean,” which seems calculated to get Patitucci, Perez and Blade to ramp it up a little more. They do and this in turn gets Shorter to toss more angular shards of phrasing at unexpected times. (See what you do with this one! Wait! Think fast! I got another one.) Taking in all this freewheeling interplay is like making one’s way through a murder mystery written by a surrealist poet. There are enough familiar signposts of the genre to string you along, but the prose trips you up as often as the plot.

7.) On record, it’s engrossing; on-stage, it’s challenging, but no more so than a Bartok string quartet. (You’ll have plenty of opportunities to find out as the beginning of Shorter’s ninth decade is celebrated in live performance here and elsewhere throughout the year.) Still, many listeners coming with their own preconceived notions of what jazz is, or should be, find this quartet’s method too arbitrary and unfocused. Some might suspect the quartet’s colloquies are little more than expanded, busier editions of the airy, abstracted interplay in which Shorter and his old friend Herbie Hancock engaged with mixed results in their 1997 duet album, 1+1 (Verve).

8.) I’m nowhere near as negative, but I understand why others are. When Shorter edged his way back into full view less than twenty years ago, I hoped he’d carry with him some hooks and melodies evoking the familiar, relative solidity of “Speak No Evil” or “Adam’s Apple” – which, lest any of us forget, were considered pretty far out in their own time by those who left their hearts and heads with hard bop and cool jazz. It would seem that Shorter, whose place in history as a composer is safe and secure, now wants to find ways of inventing off the imperatives of a given moment, just as Miles Davis insisted on doing to the end. He’d just as soon share such moments with his team, the better to see where they can take him. I don’t mind the extra work they give me because as a listener, I’m taking the leap with them. True, I wouldn’t mind a net, or even a soft, wet towel at the bottom. But if “Airboy” can fly through the thickest, stickiest obstacles, Shorter believes we should at least try. You may come out the other end thinking bigger than you did before — or at least, more different.

May 30th, 2013 — jazz reviews

Dammit.

I had not only hoped, but also expected that Mulgrew Miller would have one of those lives and careers that endured for decades longer than he was allotted. He seemed destined to become one of those gray eminences of the jazz keyboard who would be around for another generation or two as a living exemplar of jazz piano’s essential verities very much in the manner of Hank Jones, Tommy Flanagan, John Hicks, Kenny Barron and Barry Harris. He’d found a niche at William Paterson University as director of jazz studies in which role he formally – and from the evidence here, effectively – carried out what he’d been doing informally since his 20s: influencing and mentoring younger musicians eager to follow his example.

As others have been pointing out since yesterday and will likely continue to do so over the next several days, Mulgrew Miller played with a faultless blend of grace, lyricism, clarity and unassuming resourcefulness that threaten to attract the label of “jazz pianist’s jazz pianist.” While this is intended as a compliment (and there are far worse things people can say about you), it also feels reductive, inexact and inefficient – especially when one gazes at the vast and expanding field of jazz pianists who have legitimate claim to that title. Each of us, in whatever trade or calling we pursue, is the sum of our accumulated influences and experiences; it’s what we do with that internal file that matters. When I listen to Miller play, I hear a generosity of spirit, inventive enough to keep your attention, yet deeply grounded in the rhythmic and harmonic foundations of what, for want of a better term, is considered “post-bop” jazz. You don’t always have to bend or twist tradition out of shape in order to get a rise out your listeners. You can endow the familiar with such authority, power and dynamism that it achieves a kind of eloquence that lingers in the imagination. As a leader and as a sideman, Miller hit those points so frequently that he created his own posse of devotees who followed him from an evening’s session at the late, lamented Bradley’s in the Village to whatever album was lucky enough to have him in the roster.

I’m lucky, in any event, to still have some of the now out-of-print discs he recorded in the early-to-mid-1990s for Orrin Keepnews’ Landmark label and on Steve Backer’s Novus series. (My favorite from the former: 1992’s Time and Again; from the latter, 1995’s With Our Own Eyes. They’re both worth hunting for in used-music bins, on- or off-line.) He also assembled quite a catalog as a leader on the MaxJazz label, especially the two-disc Live at Yoshi’s trio sessions. He always seemed so prolific and busy that you took it for granted that his protean work ethic would receive even greater rewards further down the road with the kind of wider recognition that reached Flanagan, Jones and others in their golden years. But he – and we – have been cheated out of that prospect. Dammit. Again.

May 24th, 2013 — movie reviews

IMMEDIATE REACTION: I had a good time. I expected to. I needed more.

By now, unless you’re sticking your fingers in your ears and going “La-la-la-la” whenever somebody brings the matter up, you’ve probably heard that Star Trek: Into Darkness is supposed to be a riff on 1982’s The Wrath of Khan. Either I’m on the wrong meds or more senile than I imagine, but wasn’t its predecessor supposed to be a rejiggered version of Khan? And if so, is this how it’s going to be from now on, all these new actors in old roles and “classic” uniforms replaying variations on the same story (e.g. evil madman seeks apocalyptic revenge for real and/or imagined crimes)?

If so, then I guess nobody wants to make Star Trek movies any more. Because, let’s face it: Into Darkness isn’t a Trek movie. It’s got all the characters from Trek and the actors who play them are all very good; in one, maybe two cases, even better than their predecessors. But it’s more a movie about Trek than it is a Trek movie. It roots around the attic, appropriating old tropes and familiar names to make the devotees nod in recognition. But what I liked most about J.J. Abrams’s 2009 reboot was its impudent intent to make everything new while remaining attentive to the basic enthusiasm for human possibility that made Gene Roddenberry’s franchise linger for so long in the collective unconscious. (From one dedicated, mildly crazed TV show-runner to another…) Abrams’s follow-up, by contrast, seems content to use Kirk, Spock, Scotty and the rest as action figures that serve the corporate model for summer thrillers; most especially, the Great American Multiplex’s persistant yearning for revenge fantasies along with the attendant surges of explosions, kick-boxing, mass carnage and the obligatory, egregious deaths of beloved father figures. (Be warned: I’m going to respect the “NO SPOILERS” mandate only so much. If you care that much about what happens in this movie, you’ve had plenty of time to see for yourselves.)

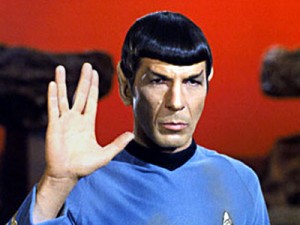

True, I wasn’t bored. Which surprises me since there was so little about In Darkness that was new, either in the plot points germane to the Trek mythos or in the usual heavy machinery assembled for standard-issue popcorn phantasmagoria. In fact, I bet the hard-core Trekkers (sic) had themselves a fine time pointing out all the scenes, set pieces and dialogue that had some connection with any and all of the varied Star Trek TV shows and movies. I bet if they tried really hard — and, trust me, so many of them don’t need to try – the SF-movie savants could point out references to other big-ticket movies in their favorite genre. Independence Day cornered the market on such shamelessness, only no one to this day considers it shameless. (It’s a classic, doncha know?) Whatever you call it, this sampling would be barely tolerable if it weren’t offset by the pleasure you get from watching the cast settle into their retrofitted characters. Chris Pine’s Kirk, though properly brash and impulsive, doesn’t yet have the William Shatner strut, though he seems to be quietly assembling his own brand of hauteur to carry into future episodes. Zachary Quinto’s Spock here shows more of the character’s original diffidence; of all the new actors, he’s the most thoroughly comfortable in his (tinted) skin. I still do not buy the office romance between Spock and Zoe Saldana’s Uhura for a nanosecond, but I am loving how she’s taking advantage of Trek 2.0’s greater breadth and depth of her character’s conception. I wish there were much more of John Cho’s rigorously circumspect Sulu, Anton Yelchin’s super callow Chekov and Karl Urban’s somewhat constrained Bones McCoy. I can’t yet tell whether Abrams and his team aren’t quite into the idea of McCoy, which would be a fatal mistake, or whether Urban doesn’t yet have a handle on him. The writers do seem very fond of the idea of Scotty rendered by Simon Pegg as a puckish grump with overcompensation issues. The revision plays to Pegg’s strengths and I’m guessing this series has bigger plans for him than they do for Urban – which would, again, be a big mistake since Trek’s classic verities are rooted in the tug-of-war between the hyper-passionate ship’s doctor and the coolly rational First Officer.

But I’m no longer sure Abrams really cares about the foundations of the old Star Trek as he does in critiquing, if not subverting Roddenberry’s vision. Let me put it another way: Why bother doing the Khan story, not once, but twice? Is it just to show how you can build a better Enterprise? As much as we love these characters in action no matter who’s playing them, it wasn’t just who they were or what they did, but what they represented to us back in 1966: Hope for the future. We’ve not only made it further out in space, but we seem to have managed to make ourselves better, smarter, more tolerant people. We figured out how to live together so well that we seem to be able to get along with people from other planets without being freaked out by the shape of their ears. Now what? That’s what we came for every week. What do we do with this wider perception of our own humanity as we head out yonder? Just as important, what DON’T we do? What is it about this expanded knowledge that keeps us from acting as stupid as some of the beings we encountered on this five-year mission, human or extraterrestrial?

These are the kinds of questions we counted on science fiction to engage, if not necessarily answer. And while we dug watching Kirk and the crew in all those cool martial-arts matches with Klingons and Romulans, the action sequences were access points for the question we knew Star Trek had to ask at some point every week: What does it mean to be human? Into Darkness is into the action sequences, but they seem placed there to sustain our thirst for retribution, which the movies seem to have been exploiting ever since (I’m going to say) 9/11. We no longer seem interested in seeking new life and new civilizations, but in kicking ass and taking names of those bullies who slaughter innocents and blow up our buildings. This yearning for the big win over terror may be who we are. But is it who we want to be? If Abrams and his co-writers are serious about this five-year mission the Enterprise is about to begin, maybe they’ll allow us to find out. But I don’t hold a lot of hope about this. Maybe that’s who I am.

May 3rd, 2013 — jazz reviews

The best jazz recording of 2012, much like science or magic, doesn’t easily yield its secrets – which is the main reason it didn’t make my Top-10 list. I simply didn’t get to it all in time. Still, with or without me (and gratifyingly so), Wadada Leo Smith’s Ten Freedom Summers has by now received most of the formal acclamation it deserves: Finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in music, awards from the Jazz Journalists Association for Smith as musician and trumpeter of the year, a three-night live premiere last week at the Roulette in Brooklyn. I suspect that once the four-disc set on Cuneiform Records seeps into the shared consciousness of receptive listeners, it will continue to provoke, haunt and inspire. The greatest music – the greatest anything – doesn’t end when you stop absorbing it. Your reactions, primary and secondary, are part of the artistic process. They’re supposed to be, anyway.

Each of the nineteen compositions in Smith’s five-plus-hour opus announces itself as a chapter in American history from the 1857 Dred Scott case to the 9/11 terrorist attacks. But the thematic core of Ten Freedom Summers, as its title suggests, is the decade of national transformation that began with the 1954 Supreme Court decision declaring school segregation unconstitutional and the 1964 summer that saw both Congress’s passage of the most sweeping civil-rights legislation since Reconstruction and the Mississippi “Freedom Summer” Project during which activists risked (and lost) their lives trying to enfranchise the state’s besieged African-Americans. With Smith on trumpet leading both his Golden Quartet/Quintet of pianist Anthony Davis, bassist John Lindberg, percussionists Pheeroan ak-Laff and Susie Ibarra and the nine-member Southwest Chamber Music Ensemble conducted by Jeff von der Schmidt, the work spools forth as a meticulous inventory of mood more than a sweeping pageant of struggle. It doesn’t chronicle its noteworthy events so much as search for their deeper emotional currents and, in doing so, compels the listener to react to history beyond text and shadow – and even further beyond the blithely-dispensed shorthand of newsreels, archival photos and sound bites.

I wonder, though, whether I’m probing or merely projecting whenever I hear some of its chapters. Just to take one example, the piece entitled, “Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott, 381 Days.” It begins with a major-key dirge by Smith’s trumpet, with a tone and tempo reminiscent of such mid-1960s elegiac milestones as Lee Morgan’s “Search for the New Land” and John Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme.” One can easily interpret this table-setting incantation as signaling the no-turning-back-now gesture by Parks in her epoch-making refusal to sit in the back of an Alabama public transport. Then, for several bars afterward, a chugging 4/4 beat, driven by ak-Laff with bouncy strides, conveys the “381 Days” of the resultant boycott, which forced hundreds of domestics, office workers and laborers to walk instead of ride to work and shop, thus representing the first of the era’s significant civil-rights marches.

I’m confident I’ve sussed that out correctly. But when I hear the strains of bluesy strutting at either end of “Thurgood Marshall and Brown Vs. Board of Education: A Dream of Equal Education,” am I being cued to imagine the swagger and bravado of its eponymous heroic lawyer making his way through several litigious hurdles to reach his finish line at the Highest Court in the Land? And would I know enough to respond to such cues if I didn’t know what its title was? Or, for that matter, know who Thurgood Marshall was and the kind of ribald, larger-than-life figure he was?

It helps to know the history behind the music. But it’s not necessary. Because even if you can sense why Smith and his musicians make the choices in what they play and how they extend their ideas (together or separately), it’s the spacious-skies expansiveness of the concept itself, its willingness to do the unexpected – a segment on the “Black Church” that’s all swirling chamber music and no gospel tropes whatsoever – and let you deal with its implications, that allow you to sense that “freedom” is far more than the theme of Smith’s work here. It’s both his method and his objective.

Smith, after all, was forged in the crucible of what, for want of a better description, we still label “avant-garde jazz.” And what would be a better description? There are so many options. Some like “progressive jazz,” though you kind of feel an anachronistic draft when you hear those words. Others cling to such sixties taglines as “New Thing,” “Fourth Stream,” “Outside” and even “Free Jazz,” though some of the renegades of subsequent decades embraced old-school polyphony that kept things flying in fairly close order. Gary Giddins quixotically tried to coin the word, “parajazz” (or was it “Para-Jazz”?) as an all-purpose umbrella. I like it, but I can’t find anybody else who does.

I also like “creative music” — bringing us back to Smith, who was part of the groundbreaking Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) that nurtured and/or inspired such experimentalists as Henry Threadgill, Anthony Braxton, Roscoe Mitchell, Joseph Jarman, George Lewis, Leroy Jenkins and many more. Their music was as idiosyncratic, original and unconventional as they were. Jazz fans who drew their lines at whatever Miles Davis was doing in 1965 (if not sooner) thought the AACM and their kind were too “way out” to even taste. But back in the seventies, I warmed to the freewheeling, sometimes breakneck invention of the renegades. It’s true they made mosaics out of traditional rhythmic pattern and carried thematic ideas down dark alleys and wooded glades you never thought of visiting. But as with avant-gardists of the past, they weren’t upending the order-out-of-chaos imperative of art as much as encouraging listeners to re-fashion or, at least, reconsider their own notions of order. In other words, they weren’t the only ones creating the music; you had to join in the process, too. And where previous generations did so by dancing, we did it by thinking or feeling our way through the changes.

Smith, now 71, has for decades advanced his own vision of creativity into finding new ways of fusing improvisation and notation. (He explains this process in far greater detail here, though, as with his music, one run-through won’t be enough.) Ten Freedom Summers uses the late 20th century’s upheaval to apply firmer context to the process. Those unaccustomed to such compulsively creative composition may think it’s haphazard, even if they know the historical facts being represented or dramatized. But as it was with the avant-garde’s loft concerts of the 1970s or for that matter, some of the late, lamented Knitting Factory’s wilder nights of the 1990s, the whole idea was to listen and to be attentive always for whatever is familiar in one’s own memory, private or public, and for what could be something you never knew before. From such surprises, you can make your own connections to this freedom struggle – or any other such struggle you can imagine. It may well have been this openness to possibility that the Pulitzer committee recognized in almost-but-not-quite giving their top prize to Ten Freedom Summers. If so, then it’s a whole way of thinking about music, and not just jazz, that’s received its just desserts.

April 16th, 2013 — movie reviews

If you retold Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by moving it several hundred miles upriver, replacing Huck with an older, craftier version of his friend Tom Sawyer and making Jim a younger, more articulate family man, you might well have the true-life, mid-20th-century’s Greatest Story Ever Told: How Branch Rickey and Jackie Robinson engaged on a perilous two-man odyssey to force racial integration down major-league baseball’s throat and make America like it. The difference being that Huck, in refusing to turn Jim over to slave hunters, only thought he was going to hell. Jackie Robinson, throughout that trailblazing 1947 season of triumph and torment (mostly the latter), came as close to an earthbound purgatory as any mortal should have endured.

It’s a story that, much like Huck’s, never loses its power to simultaneously unsettle and inspire. And as with Twain’s masterpiece, no feature film could adequately do it justice, though at least one, The Jackie Robinson Story (1950), made a crude, earnest attempt with the genuine article sportingly, if woodenly, starring as himself. (It’s still interesting to see as a curio of its time and for watching two of our greatest actresses, Ruby Dee and Louise Beavers, on-screen even if they’re only playing silhouettes of Robinson’s real-life wife and mother respectively.)

42, the freshest rendition of the Jackie Robinson parable, is shinier and more authentic than its predecessor – which doesn’t mean it’s any less earnest or doggedly elemental in its execution. I would have no trouble whatsoever exposing a young girl or boy to Brian Helgeland’s digitally enhanced diorama. (It should probably come with one of those labels Milton Bradley used to put on its board-game boxes saying, “Ages 7-14.”) As Robinson, Chadwick Boseman emits the same smoldering intensity as the genuine article while suggesting, at times, some of the prickly-heat feistiness the major leagues would see once he no longer had to turn the other cheek. His scenes with Nicole Beharie as Rachel Robinson have a genuine ardor and unassuming sweetness rare in any movie with an African-American romantic couple. I’d be tempted to say it was a breakthrough for black movies if I thought the movie was all about them. And it isn’t.

For what the story of Jackie Robinson’s trial-by-fire has by now become (in ways that Huckleberry Finn never could) is an occasion for America in general and white people in particular to congratulate themselves on their capacity for change. Boseman’s Robinson may have more dimensions than the version Robinson himself enacted sixty-something years ago. But he is still less a fully fleshed character than a stoic presence, sustaining unspeakable punishment for his country’s sins. This doesn’t in any way mitigate his heroism or importance. But much as America’s astronauts, however fearless, were basically instruments of their country’s scientific and political will, Robinson was the instrument of one man’s far-sighted vision – and determination to overcome his own shame for his beloved game’s racial myopia .

We’re talking, of course, about Branch Rickey, 42’s true protagonist, the man who pulled the strings for this “great experiment” and made sure none of them were clipped. There sometimes seemed almost as many leading men in Hollywood yearning to play Rickey as there were wanting to play Chet Baker, though a far more motley group in the latter queue. Harrison Ford makes the most of his rare opportunity to go big, broad and hard. I hear some gripes about Ford going too far over the top – which discloses nothing so much as the complainers’ ignorance of baseball history. Outside of, say, Bill Veeck, Larry McPhail and George Steinbrenner, Branch Rickey is the only baseball executive whose larger-than-life presence is worthy of a movie. If anything, Ford seems at times a little too conscious of Rickey’s many facets (which, in Red Smith’s immortal turn-of-phrase, were all turned on). But it’s such an endearing performance throughout that you even enjoy Ford’s straining to get it just right.

The rest of the actors pretty much carry out their roles in this parable as expected, though history would have been better served by showing that Philadelphia Phillies manager Ben Chapman (the admirable, under-appreciated Alan Tudyk) wasn’t the only one in that team’s dugout ragging Robinson so viciously. (The late Richie Ashburn was one of the few players on that team in that era who owned up to such taunting and expressed his deep regret for it.) Poor old Dixie Walker (Ryan Merriman) must once again be properly humiliated for trying to whip up his white Dodger teammates in opposition to Robinson – though in later years, he pleaded for forgiveness from the press and public. As for Christopher Meloni’s Leo Durocher, he’s such a magnetically funny and vividly rendered character in his precious few moments onscreen that when he’s compelled to leave the team (and the movie), you wish you could follow him out the locker room door to watch what happens to him – and, of course, Laraine Day (Jud Tylor). There’s another movie waiting to be made, and if they’re smart, they’ll let Meloni continue in the role.

As for 42, it may not cut as deep as most of us would like. But it may say something about my own diminished expectations of Hollywood that I doubt we’re going to get a better movie version of this story for some time to come. Dioramas and comic books are what sell in the multiplexes these days and as long as the outlines and colors are reasonably aligned and the proper emotions are aroused, then I’m willing to settle for harmlessness as a virtue; just as long as nobody tries to sell 42 as genuine progress. Popular culture as a whole still can’t accommodate the complexity of a real-life Jackie Robinson who in the years since his arduous rookie season was fueled by unceasing rage and uncompromising passion for justice. Indeed, Hollywood movies in general still can’t adequately deal with emotional complexity of any kind — and may have stopped trying.

March 22nd, 2013 — jazz reviews

A big shout out to those of you who responded to the previous post on Thomas Chapin’s newest CD set, Never Let Me Go. Lots of love out there for Tom, who deserves all that & more. Among the many who responded: Stephanie J. Castillo, who is trying to pull together enough funds for a full-length documentary about Tom. Here is the site — with all the information on the Kickstarter campaign & every important link related to Tom Chapin’s life & legacy.

Whatever you can do, patrons. The Home Office will be grateful. The campaign has roughly a week to go & they’re still not near the goal of $50,000. So she’s asking people to take part in the “100 X $100 Group Give.” Do the math. If 100 people give $100 over the next five days, $10,000 from the Group Give will help meet the $50,000. Of course, all amounts – small and large — will be accepted.

The previous post said mostly everything I needed to say about Tom…except, maybe….

OK, bear with me. In February, 2008, a memorial concert for Tom was staged at the Bowery Poetry Club. There was more than enough words & music to share that night. But I felt somewhat bereft, being only a spectator & knowing Tom as I did. It wasn’t until a couple days afterwards that the following fantasia rolled out of me. I wish it had rolled out that evening, but I guess it wasn’t ready.

So with your kind indulgence, here’s that side-dish of speculation mentioned on the marquee, a meeting that never happened, but should have. It’s a little wig-bubble The Home Office is labeling:

WHEN MILES MET TOM or THE FINAL FRONT LINE

It’s September of 1991 and a gravely ill Miles Davis is, as Lord Buckley would put it, not merely “on the razor’s edge”, but on the “hone of the scone,” whatever that is, if that is what it is.

Anyway, Miles is in his Malibu manse, semi-conscious, hooked up to all manner of wires and tubes. Deep down, he knows that this is all pointless. It definitely feels like Checkout Time’s arriving at any minute and all he can do is drift in and out of reality, trying to take in as much as he can before the lights go completely dark.

He can dimly hear a radio piping in music from another room. Some dumbass has it tuned to a jazz station. Fuck that, Miles thinks. Anything but that! And it’s not just plain old jazz, but that squealing and squawking shit that Trane helped spread like a virus. I do not need that shit taking me out. I’ll take Manto-fuckin-vani over this!

Just like that, his espresso eyes, which were starting to cloud over mere seconds ago, sharpen into hard, clear points as he hears this gorgeous, passionate alto sax solo soaring and slicing its way through the miasma. He’d love to sit up so he can hear better and, to his astonishment, he almost feels as though he could. The keening, probing sound continues to jab its way into his consciousness. He digs the raw aggression, the rippling arpeggios and, more than anything else, a tone that sounds the way light would sound if light could make sound. Mothafucka can play his ass off!!

At that moment, a male nurse walks by his bed. Miles emits soft murmurs, which is the best he can do. The nurse doesn’t hear anything. Drastic measures are called for, so Miles attempts to simulate some sort of spasm. It’s lame, but it works. The nurse walks over.

“Miles?,” the nurse whispers.

“Hmmrefffrrr,” Miles says.

“I’m sorry. Do you need anything?”

The music’s almost over. If only someone would take these tubes out of his goddam nose…

“Mwhegfffrrgggrdr.”

“Mister Davis,” the nurse leans close to the parched, scarred lips. “I still can’t…”

A raspy bullet, whatever’s left deep inside him, is violently pumped through his ravaged larynx into the idiot’s ear

“I SAID, who’s that on the mothafuckin radio, goddammit!”

After a series of confusing exchanges, someone else in the house, presumably whoever had the radio on, finally figures out what Miles wants to know. He tells him that there was this bootleg tape of a young reed player out of New York, used to play with Lionel Hampton, but he’s just starting to make a name for himself in the downtown scene. Album’s not even out yet…

Miles can sense the steam rising within him. It feels good, almost human, but he still sounds exasperated and weak at the same time. “Who…is…that…motha…fucka?” Serious coughing, maybe a trickle of blood…

The name, the fool says, is Chapin. Was that his first or last name? Oh, right. Yeah, Tom. Thomas Chapin…

Orders are rasped. Call that station! Get a copy of that tape! Find out where that mothafucka lives! Now, goddamit! And so on…

Sooner than it’s possible to imagine, given the circumstances, Miles is on a long-distance call with Tom, who thinks at first that someone’s fucking with him. When he realizes, it’s not a joke, he thinks: Oh, my God! I’m on the phone with Miles Davis! And he sounds TERRIBLE…

“Lissen, man,” Miles says weakly, gasping for air, “how soon can you get your ass out here? With…that…sax…”

“Um,” Chapin says, not sure he heard correctly, but he answers anyway. “I dunno, Mister Davis, when do you…”

“Now! Yesterday! Last week, goddammit! I’m dyin’ out here, man! I want…(wheeze)…I want to record with you…Just for one time…”

Chapin is now certain someone’s messing with his head, big-time. He observes, tentatively, delicately that Miles may not…make it…by the time he flies to L.A. even if he leaves that second…

“Well, then you better hurry your ass up” Click.

From here, it’s too quick and hazy to keep track, but Thomas Chapin has somehow made the next flight from JFK to LAX. Miles, or someone close to him, takes care of traveling expenses and studio time.

Time movies fast. Here’s the studio, but where am I, Chapin wonders. Is it dawn or dusk? Where did this rhythm section come from and how many of them are there?

Miles is wheeled into the room, connected to a respirator. There’s no way, Chapin thinks. But the horn is in Miles lap, poised for action. Miles, forgoing amenities, croaks out the only three words he will say to Tom Chapin all day:

“Follow…my…lead.”

What follows is the kind of music that wills itself forward without stopping for thought or breath. It free-associates itself into something that’s neither funk nor free, neither “inside” nor “outside”, neither modern nor post-modern, neither swing nor rock; more to the point, it’s none of these things exclusively but a dense, yet buoyant amalgam of mid-to-late-20th century music’s varied precincts, high, low and in-between. It is, in other words, music that only Miles Davis could have set in motion – and that only Thomas Chapin’s luminous tone and inquisitive chops could help him finish.

Ten hours and six tracks later, the last testament of Miles Dewey Davis is in the can. He returns to Malibu to await the final call, which comes as Tom is in mid-air somewhere over western Pennsylvania on his way back to the city…

The session? Well, you know what happened with that session. By now, everybody knows what happened with that session and how it helped make jazz’s next century a …But that’s another fantasy, isn’t it?

March 20th, 2013 — jazz reviews

The first time I heard him play was sometime in 1988 on an LP (ask your parents, kids, because I hear they may be coming back) entitled, The Sex Queen of the Berlin Turnpike, a jazz-and-poetry mix written and produced by a central Connecticut crony of mine named Vernon Frazer, novelist, raconteur, boxing aficionado and bass player who’d provided musical accompaniment to his readings here and, in years to come, at such venues as the Nuyorican Café and the Knitting Factory.

As I listened, I became acutely aware of this flute coiling around Vern’s incantations and bass lines in lucid, deceptively simple patterns. As I grew up a flautist manqué, however reluctantly, I paid attention when people did unexpected things with the instrument, especially in jazz. And whoever was playing had nailed down a lyrical, probing style that refused to lean heavily on the flute’s naturally pretty tone. (The tone wasn’t pretty. It was beautiful, rich and – was it possible? – evenly layered.) And then I heard the alto sax solos. They could burn like scalding water. But they also soared; sometimes like jets, other times like gliders. More than anything, it was the relentless invention, the let’s-try-anything ingenuity that knew how to swing, bop and blow the blues in the grandest manner, but could step “outside” conventional changes with a nonchalance that seemed highly evolved even for the greyest of beards.

I checked the name on the cover: Thomas Chapin. Hadn’t heard of him before that point and was chagrined at myself for not paying attention. I’d assumed he was this lesser-known veteran of the black music wars who likely spent the previous decade-and-a-half trolling through lofts along the eastern seaboard. “Who is this Thomas Chapin cat?” I wrote Vern, who in turn told me he was this barely-thirty-something white guy from Manchester, Connecticut.

Manchester? Really? I’d spent part of my early newspaper years writing about that east-of-the-river suburb and, whatever its myriad virtues and defects, the next-to-last thing I’d have expected was someone who could wail like this. When I played this record to another colleague from those long-ago Hartford Courant days, his head swiveled as sharply as mine had to the sound of Chapin’s alto. When I told him who was playing and where he was from, my friend shook his head. “Shit, man,” he said. “Nobody from Manchester ever blew like that!”

It’s been fifteen years since Thomas Chapin died at just 40 years old and I still find myself wondering what he’s been up to. I keep thinking he’s got to be on some club’s weekend schedule, leading a trio or quartet in support of a new disc or performing yet another homage to his idol Rahsaan Roland Kirk. No matter where Tom would be, he would be turning heads, winning friends, encouraging people to come over to his side, no matter how forbidding or unconventional the setting. That’s what he always did, on- or off-stage. That’s why we miss him.

He was a member in good standing of the crowd of cutting-edge dynamos who waved the progressive-jazz banner throughout the eighties and nineties in downtown New York (a scene whose central HQ was that aforementioned Knitting Factory). Yet he also turned heads among more-traditional-minded listeners as a distinctive and highly accomplished post-bop player with a bright, lightly jagged tone and a prodigious, often-stunning range of expression. As with generations of musicians who had apprenticed under Lionel Hampton (in whose big band he’d worked for five years), Chapin carried “Gates’s” lessons of brash showmanship in his own trick-bag. But he never pandered to or shortchanged expectations, whether swinging from the core of a hard-bop standard or generating torrents of chromatic density off a simple riff.

The straight-ahead side blooms like fireworks on Never Let Me Go (Playscape), a recently-released triple-CD of Chapin leading quartets at two New York venues. The first two discs are from a November, 1995 show at Flushing Town Hall with pianist Peter Madsen, bassist Kiyoto Fujiwara and drummer Reggie Nicholson. The third disc teams Chapin and Madsen with the bass-drum tandem of Scott Colley and Matt Wilson at the Knitting Factory on December 19, 1996 – Chapin’s last live date in New York City. (He’d been diagnosed with leukemia the following year.) Though Chapin’s last studio recording, 1997’s Sky Piece, remains the one true gateway to his life’s work, Never Let Me Go evokes the warmth of Tom’s personality and the exhilaration he could communicate even to those who may not have fully appreciated his chosen idiom.

Ecstasy leaps from the first track, “I’ve Got Your Number,” whose chord changes provide a gauntlet for Chapin’s breakaway speed and power. There was never anything tentative about his attack; not even when, on the silky “Moon Ray,” the tempo gears down to stealth mode and Tom summarily shifts to shrewder thematic tactics. Along with his many other gifts, Chapin easily complied with Lester Young’s directive to “sing a song” when he played – which meant, as Prez suggested by example, to find the songs within the song that needed to come out. More than most of his downtown confreres, Chapin always exercised this prerogative, even on songs that weren’t part of the classic-pop canon as exhibited here on both “You Don’t Know Me” and “Wichita Lineman,” whose melodies Chapin irradiates with such conviction that you get the feeling he could have, in time, single-handedly embedded them both in the traditionalist fake-book.

His own compositions become occasions for Chapin’s more imaginative dramas of harmony and rhythm doing their approach-avoidance ritual. These are most prominent on the Knitting Factory gig; it must be noted that Matt Wilson, whose own embraceable style and personality are mirror images of Chapin’s, opens wider terrain for both Madsen and Chapin to lunge at the edges of time and space. On such pieces as “Big Maybe” and “Flip Side,” whatever ambiguities, discordances and incongruities play their way through each solo do so from a solid core, which Wilson tends with inviolate calm, but also with a gentle persistence of vision. Madsen makes his presence even more pronounced on the latter set; he builds his own model airplanes to fly as eccentrically, yet as emphatically as Chapin’s own. Together, this group could have helped make the cutting-edge a place where all would be welcome, exalted and, eventually, transformed. It’s nice to think so anyway.

When someone dies as prematurely as Chapin, there usually come in his wake several voices inspired by his example to fill the void. (Think of all those bright, hot horns who picked up where Clifford Brown left off. Or all those actors who are still filling in the blanks left behind by James Dean’s car crash.) In the decade-and-a-half since Chapin’s death, those examples are harder to find, especially his ability, or more accurately, his impulse, to bridge the gap between progressive and traditional jazz music – or to, at the very least, extend what critic Jim Macnie characterized as the “dialogue” between two wary, warring factions. As jazz kept shifting shape at the close of the century, bending and twisting itself into new forms while struggling with how much of its past forms it should retain (or shed), Thomas Chapin offered a model for the music’s future by making his own art pliant, inquisitive and open enough to accept whatever the times demanded. I don’t know whether the “amalgam of freedom and discipline” described in Chapin’s Allmusic.com biography could have slowed down or even stopped jazz’s free-fall in a music marketplace that became even more mercurial after his death. But I’m far from alone in wishing he’d had more time to try.