January 3rd, 2014 — jazz reviews

If you heard my annual song-and-dance on the Dec. 26 edition of “The Colin McEnroe Show” on Hartford’s WNPR-FM, you’re aware of at least one of my “oopsie” omissions from my Best-of-2013 jazz recordings list. And since that particular omission gets more embarrassing every time I listen to it, I am obliged to start 2014 by elaborating upon my mea culpa – and mention at least one other omission at length. And since we don’t want to be too negative with a clean slate, I’ll add some spare change on the first new disc of the year that’s got my (mostly appreciative) attention.

Cecile McLorin Salvant, “WomanChild” (Mack Avenue)— Whenever a vocalist catches fire on the jazz scene, it often happens after he or she has been out in the world for some time. In the nineties, as in the case of Shirley Horn or even Abbey Lincoln, there was the phenomenon of rediscovering artists who’ve found a glorious second wind carrying them late in life to unexpectedly fresh levels of expression and power. Rarely do young jazz singers make your head turn at Jump Street the way Willie Mays raised heart rates with his first-at-bat. Which makes Cecile McLorin Salvant, at just 24 years old, an especially rare talent. To repeat what I said on Colin’s show, she is simply the most exciting young jazz vocalist I’ve heard in at least a quarter-century, which I suppose constitutes a generation. To move down the checklist: Tone: Check; Dynamics: Check; Phrasing: Check – and she has the ineffable qualities that in their rawest form we recognize as “soulfulness.” But even with all those attributes in her tool kit, Salvant makes her biggest impression on “WomanChild” with the intelligence and breadth of her repertoire. She makes a couple of customary stops on the standards tour (“I Didn’t Know What Time It Was”, “What a Little Moonlight Can Do”). But she also reaches waaaaay back to the less-travelled, but venerated pathways cleared by Bessie Smith (“St. Louis Woman”), Clarence Williams (“Baby Have Pity On Me”), Fats Waller (“Jitterbug Waltz”) and, most stirring of all, Bert Williams (“Nobody”). When someone so young can do so much at once, the immediate worry is that she’ll spread herself too broadly before she Finds Herself (whatever that means). I prefer to enjoy the rush of potential and possibility as she steps to the plate for another cut at history. I also want to shout-out to her comparably promising pianist Aaron Diehl, who flashes his own bright-burning composite of lyricism, eclecticism and dynamism.

Jane Ira Bloom “Sixteen Sunsets” (Outline) – You could more accurately title it, “Sixteen Ballads,” but “Sunsets” sounds more appropriate, metaphorically. And as with reach sunsets, each of these ballads enraptures in different ways. She uses what she loves about the classic melodists, including Gershwin (“But Not For Me”), Arlen (“Out of this World”) Waldron (“Left Alone”), Kern (“The Way You Look Tonight”) and Weill (“My Ship”) and brings their deceptively simple designs to her own compositions, including “Primary Colors,” “Too Many Reasons”, “Ice Dancing” and my own favorite, “What She Wanted.” Her soprano saxophone can make your skin tingle as few others on her instrument ever have. If this disc, as with Salvant’s, had arrived in my mailbox before I turned in my ballot to the NPR Jazz Critics Poll, my Top Ten List would have been very different.

Matt Wilson Quartet with John Medeski, “Gathering Call” (Palmetto) – What an pleasurable way to start the New Year: Hard bop, late-1960s/early 1970s vintage, played without apologies and with an open-hearted joie de vivre that can make even the hardest of hard-core progressives wonder why they ever thought the genre was old news. I suppose some would still think it old news, even if they liked it. But there’s nothing musty or creaky about Wilson’s easygoing command of the trap set in all situations or his group’s saucy renditions of such Ellingtonia as “Main Stem” or “You Dirty Dog.” The quartet also pays homage to the recently departed bassist Butch Warren by playing the latter’s “Barack Obama” with the delicacy, wonder and cautious optimism you suspect the composer had in mind as he wrote it. You’re happy for the leader, one of the perennial Good Guys in the jazz business, which in turn makes you happy – and hopeful – for the business itself.

December 25th, 2013 — movie reviews

Top Ten? Worst Ten? Ugly-But-Brilliant Ten? I don’t know. Like…why?

There’s more than one way to sum up a year. I should start this off by saying that, contrary to what some may say, this was one of the better overall years for moving pictures and I wasn’t expecting a whole lot, given the way episodic TV has been routinely eating cinema’s gourmet lunch for at least a decade. With TV having one of its more mediocre fall seasons in decades, it was inevitable that the movies would get better at about the same time.

But I don’t need to give you a list to tell you that. There are many more of these lists to argue with from people who are even busier (if not smarter) than I am. What I prefer to submit is a potpourri of impressions, observations and pronouncements that will give you a general idea of how I reacted to the movies I saw this year. I’m not fond of the role of critic-as-magistrate (which may explain partly why no one’s now paying me to do it.) I like to think about what I’ve seen and talk it over with others. Don’t you? I’ve already rambled about 12 Years a Slave under what one would call a separate cover. And you can probably figure out what I liked a lot from what you see when you scroll down.

One other thing to say at the outset: Women will likely dominate the forthcoming discourse, but that’s because women gave me more to talk and think about in the dark this year than men. Or children. Or aliens. I’m not necessarily making a point here. Just saying…

The Incredible Shrinking Bullock

Because movie reviewers tend to a.) be pressed for time and/or lazy and b.) not take science-fiction all that seriously as a literary genre, it was inevitable that most of the comparisons they made to Gravity, positively, negatively or otherwise, were to other “in-space-no-one-can-hear-you-scream” movies as 2001: A Space Odyssey and Alien. These aren’t inept or in-apt analogies, given all the heavy-breathing spacesuits floating and crashing through all three movies. They just seemed too obvious. The first movie I thought of as I tossed my 3D glasses in the bin outside Gravity’s screening room was The Incredible Shrinking Man, whose visual effects wouldn’t make anybody gasp now, but were pretty cutting-edge for 1957. Both that Jack Arnold classic (which holds up better than you’d think) and Gravity have protagonists forced to deal with overpowering, inexplicable forces squeezing them in tighter spaces and erasing their options for survival. The telling difference (maybe I’d better flash SPOILER ALERT here) comes at the end when, though both heroes are literally stripped down to almost nothing, Shrinking Man somehow feels larger and more consequential as a human being despite his rapidly-diminishing state while astronaut Ryan Stone, though out of immediate danger, staggers off into a world that somehow feels bigger than she is. And this, you ask, is significant because…? Think of the difference in calendar years: In 1957, we integrated Little Rock’s Central High and, weeks later, Russia launched a beeping toy into orbit. This year, as I write this, there are barely enough astronauts working on Christmas Day to patch up an ailing International Space Station. And don’t even ask how voting rights did in the High Court a few months ago. We’re a lot better at special effects, but as for the rest…As I say, think about it.

Movie Critics of the Year

I only this year discovered the HISHE Network on YouTube and I have now become their stalker, looming at their door in anticipation of their next animated shot at a studio franchise. (No Desolation of Smaug, yet? No Catching Fire? You guys slacking or what? I’ve got other things to not do, OK?) The acronym, BTW, stands for How It Should Have Ended and, as you wits have likely discerned, the site’s proprietors do their own version of a blockbuster’s ending that makes you laugh and often makes more sense than the “real” thing. Because the guys and gals who work the controls of this site are knowledgeable fans of these genres, their send-ups are mostly affectionate. And it’s this admirable deficiency of snark that only magnifies their impact. It’s like having emissaries of Geek Nation sending out dispatches to the major studios and telling them, in essence, “We love this stuff, but we’re not idiots!”

Meh Dancing, Amazing Dance

I may be biased in favor of Frances Ha over other Noah Baumbach movies (most of which I’ve liked) because the title character’s struggle to make it as a modern dancer in post-Millennial New York City hits close to home these days. Also, because I’ve been exposed to different forms of choreography, I tend to see the movie as a kind of extended dance piece. Not that Greta Gerwig’s actual dancing is anything special. (It isn’t.) But I love the way she moves throughout this movie whether she’s leaping for the hell of it through Chinatown to David Bowie’s “Modern Love” or trudging warily along Parisian streets to Hot Chocolate’s “Every 1’s a Winner.” That’s what made me happy about this movie, which is something audiences and critics didn’t expect from a Noah Baumbach movie. Maybe he needed the dancing element to take the weight off. Maybe he needs to do it some more.

And the Oscar Wont (But Should) Go To….

It’s still early but I’m not hearing a lot of people throwing around Adele Exarchopopolos’ name as an Oscar prospect despite her sharing a Palme d’Or at Cannes and winning a Los Angeles Film Critics Association prize for Best Actress. Nothing whatsoever from the Golden Globes, even though she is every bit as riveting and dominant a presence in her movie as Sandra Bullock and Cate Blanchet are in theirs. The first and, often, last things people think of when they think of Blue is the Warmest Color are its NC-17 lesbian sex scenes. As lyrically enticing and obliquely suggestive as the movie’s English-language title may be, the literal translation of its French title, “The Life of Adele,” tells you everything there is to know about the story – which, prosaic as it sounds, is of a young woman’s education; sensual, yes, but also emotional and intuitive. She begins the narrative as a live wire who’s shy, moist and voracious at the same time. She comes out the other end, feeling…well, at the very least, drier. Sex may be explicit in Blue is the Warmest Color, but personality is not. And the beauty of Exarchopopolus’ performance is the way she instinctively gearshifts her character’s sensitivity, allowing us to infer what’s going on in her head while keeping us engaged with the unguarded emissions from her heart. Exarchopopolus will likely acquire greater dimension and skill as an actress. But I doubt she’ll ever again deliver anything as poignantly raw as this, and she at least should get something nice from Hollywood for her trouble.

And speaking of 20-something actresses…

Our Brando

Squares and aesthetes may have perfectly good reasons for decrying Jennifer Lawrence’s I’m-such-a-goofball talk-show appearances with their haphazard disclosures of butt-plugs and other adorable lapses in decorum. But I think these fluffernutter turns deepen her mystique more than shatter it. Public appearances are as much a performer’s art as screen acting and Lawrence is as foxily good at both playing to and subverting the hoary hype machine as she is at withholding her characters’ secrets in movies. Whether on the small or big screen, Lawrence keeps you on-edge. On the small-screen, you don’t quite know where her mouth is going next; on the big-screen, you don’t know what her face is going to do next. In neither case do these impulses feel calculated, though Lawrence is sure as hell is smart enough to know how to play both games better than anybody you can name at the moment. And that’s the real mystery: How does she know? How does any 23-year-old have the poise, the self-possession, the inner power to carry the multimillion-dollar tent pole that is The Hunger Games trilogy playing a teenage badass while simultaneously putting out back-to-back dynamo turns for David O. Russell as emotionally damaged older women? One imagines a similar frisson for audiences a half-century ago when Marlon Brando kept topping their expectations in movie after movie. The only difference is that Brando could never bring himself to create a user-friendly public persona the way Lawrence can. The more he ran away from celebrity’s power to diminish his artistry, the worse things got for him whereas Lawrence doesn’t seem to give a shit. She’s taking charge of her celebrity in ways that previous generations of actors can only envy and such confidence could help her dominate her era of movie acting as Brando, Nicholson or any male icon ever did. J-Law: Our Brando AND Our Cary Grant? Is that so hard to imagine? Forget the shticks with Conan and Dave. Watch the movies again and get back to me.

I haven’t seen this movie come up in anybody’s Ten-Best Lists.

Or this one either.

Finally, my three four five favorite lines quotes from 2013 movies:

“I feel like you’re breathing helium and I’m breathing oxygen.”

—Before Sunset

“Everything is not everything. There’s more.”

—Computer Chess

“When you’re in the middle of a story, it isn’t a story at all but rather a confusion, a dark roaring, a blindness, a wreckage of shattered glass and splintered wood, like a house in a whirlwind or else a boat crushed by the icebergs or swept over the rapids, and all aboard are powerless to stop it. It’s only afterwards that it becomes anything like a story at all, when you’re telling it to yourself or someone else.”

—Stories We Tell

“We’re all on the brink of despair, all we can do is look each other in the face, keep each other company, joke a little… Don’t you agree?”

—The Great Beauty

“Welcome to Heaven, mothafuckas!”

—This is The End

December 20th, 2013 — movie reviews

Can anybody make a serious, imaginative movie about slavery without being either ignored or picked at? Quentin Tarantino spent almost as much time shaking off flak for his flamboyant genre goof Django Unchained as he did taking bows and counting money. When Jonathan Demme made Toni Morrison’s Beloved into a far-better-in-hindsight movie in 1998, not even the Great and Powerful Oprah’s approbation of, and involvement in its production could make black people assemble en masse to see it when it was released. (Or anybody else. The cost was about $58 million; the movie made about $23 million, at best.)

At least, nobody’s ignoring 12 Years a Slave. It’s at or near the top of just about everybody’s year-end list of best movies. As of the second week of December, it’s made more than $35 million in American ticket sales with more expected around the bend in advance of Oscar season. Still, the movie has attracted its own high-visibility flak from such critics as Armond White, who believes Steve McQueen’s often-graphically violent rendering of Solomon Northrup’s testament as “torture porn” and “less a drama than an inhumane analysis.” David Edelstein, though he believed the movie “smashingly effective as melodrama,” is less fond of McQueen’s “cold, stark, deterministic” approach to the material.

For the record, I admired 12 Years a Slave far more than I loved it. An American/Hollywood director, no matter how smart or savvy, wouldn’t have trusted as much visually as McQueen does here. (In case you didn’t know, he’s black and British.) He isn’t afraid of stillness, of the tension and energy that reside in the act of waiting, as in the first frame, which in just showing the barely contained anxiety in the faces of slaves, gets the movie moving. That said, I doubt very much I will want to see it again. Do I need to watch, once again, a thin young woman getting whiskey tumblers thrown at her head and then having her back stripped of her ebony skin the way you strip a tree of its bark? I do not – and part of me wonders who would, or who needs to.

Still, because the movie is directed by a black man and is written by another (novelist John Ridley), 12 Years a Slave doesn’t get the same mauling Steven Spielberg’s Amistad (1997) received in some precincts for making ciphers of its mutinous African slaves and using their rebellion as a vehicle for white nobility. And I doubt very much the contrarian attacks on McQueen and his film will keep it from winning more awards; any more than Django’s critics kept Tarantino from collecting a screenwriting Oscar.

But no amount of gold statuettes will stop the haters from jumping on the next filmmaker who wants to take yet another hard, idiosyncratic shot at America’s Original Sin. The only solution: Take more shots, make more movies, go as odd, off-base, strange, funny, stern, cold, hot or heavy as the market can bear – and then, if you’ve got the gall, go further than that. There’s no dearth of material to draw upon, from the still largely undiscovered country of slave narratives to contemporary fiction by African American writers who are claiming autonomy over their ancestral experience through daringly imaginative means.

You like lists. Here are places to go for such material:

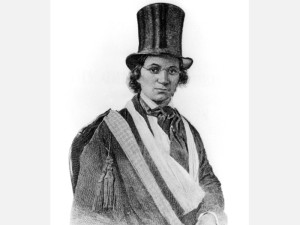

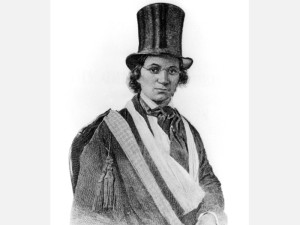

William and Ellen Craft – True story: They were married in bondage in 1846 and escaped two years later from Georgia to Philadelphia in disguise; she (above) as an invalid white man and he as “his” valet. It would take someone with an equally attuned ear for both injustice and comedy, but it could be done.

The Good Lord Bird – Being this year’s surprise National Book Award winner, James McBride’s picaresque comic saga of a young slave boy mistaken as a girl by abolitionist John Brown has likely attracted a few cautious glances from Hollywood. Sophisticated historical satires aren’t exactly meat-and-potatoes fare for multiplexes, no matter who’s involved. But it would be funny, again, if the right tone is struck.

Flight to Canada — An Ishmael Reed seriocomic pastiche that’s never received the credit it deserves for initiating a wave of black novelists claiming imaginative autonomy over their ancestral past in daring, often incendiary fashion. I can’t begin to imagine who would make a movie out of it or what kind of movie it would be. But whenever or however it’s done, it’ll be different from anything that came before.

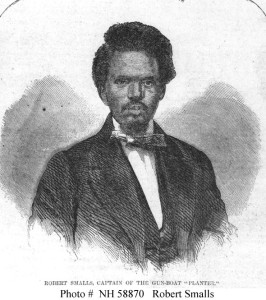

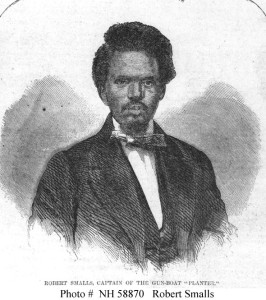

Robert Smalls Steals a Rebel Ship– Another true story; this one about a slave (above) who in 1862 commandeered a cotton freighter with a crew of 17 fellow escapees and managed to hide his identity from Confederate checkpoints, even Fort Sumter, towards the open sea until he was able to raise a white flag to Union blockaders. That alone would be a good movie, though it was just the beginning for Smalls, who later became one of the few African Americans to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives during Reconstruction. (Speaking of which, don’t you think that by now, some great movie about black folk during Reconstruction could be made to counter that damned Birth of a Nation? Just add it to the wish list.)

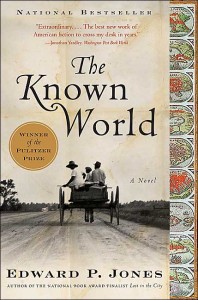

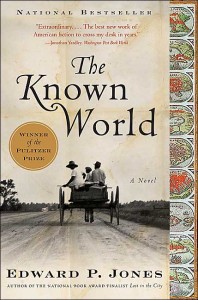

The Known World – Edward P. Jones’ award-winning novel about blacks owning black slaves already made readers’ heads spin off their necks. A movie version could magnify the shock-and-awe and I’m being REALLY optimistic when I say it could be done. But I’m betting it wouldn’t cause nearly as much trouble as…

The Confessions of Nat Turner – And, yes, I mean William Styron’s version, which has been cherished and despised in near-equal measure by black and white readers alike. America wasn’t ready for Turner in the 1830s and they still aren’t ready for him in whatever form he’s presented or imagined. Which doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be attempted.

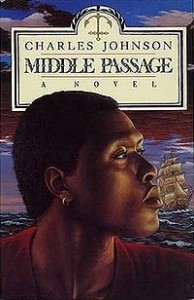

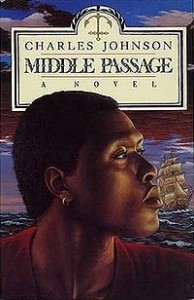

Middle Passage and Oxherding Tale — A pair of thinking-person’s ripsnorters by Charles Johnson; the former, as with 12 Years a Slave, puts a freed slave in harm’s way as he finds himself aboard a raucous slave ship heading back to Africa to pick up more “chattel.” The latter chronicles the adventures of a half-white-half-black slave negotiating his way through both worlds with philosophic insight and canny resourcefulness.

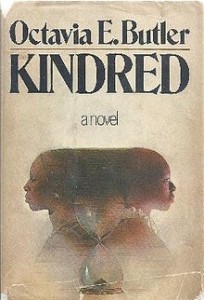

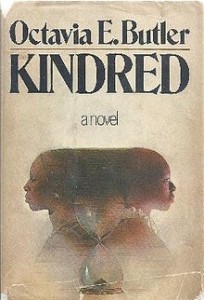

Kindred — Let me quote from an Amazon review of the late Octavia Butler’s breakthrough SF novel: “Dana, a black woman living in Los Angeles in 1976, is inexplicably transported to 1815 to save the life of a small, red-haired boy on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. It turns out this small boy, Rufus, is one of her white slave owning ancestors, who she knows very little about. Dana continues to be called into the past to save Rufus, and frequently stays long periods of time in the slave owning South. The only way she can get back to 1976 is to be in a life threatening situation.” How is this NOT a movie waiting to happen? Why hasn’t it happened by now?

And on and on and…

December 6th, 2013 — jazz reviews

Of the assorted cans of worms pried open among jazz heads on the Internet in recent years, my favorite comes from Branford Marsalis who has been calling out his peers (and, by implication, critics like me) for embracing virtuosity and harmonic invention at the expense of melodic content, which in turn was pushing more and more listeners away. “Harmonic music,” Marsalis said back in 2011, “tends to be very insular. It tends to be [like] you’re in the private club with a secret handshake.”

From that same interview: “When laypeople listen to records, there’re certain things they’re going to get to. First of all, how it sounds to them. If the value of the song is based on intense analysis of music, you’re doomed. Because people that buy records don’t know shit about music. When they put on ‘Kind of Blue’ and say they like it, I always ask people: What did you like about it? They describe it in physical terms, in visceral terms, but never in musical terms.”

The argument over whether jazz is hermetically sealing itself by being absorbed with invention-for-its-own-sake is as almost as old as jazz itself. Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray, for all their worship of literary modernism, snarled over most of the boundary-busting jazz music that came after the swing era. (People of varied generations and races are always shocked to find that Ellison disliked Charlie Parker almost as much as Philip Larkin.) Even Miles Davis at some point in the early1960s admitted that he didn’t buy jazz records of his era because “they make me too sad, man.”

I don’t get sad with what I hear lately. Once in a while, I even like being sad, and so do what Marsalis calls, “laypeople.” But there were times in the last several months when I was getting impatient with the new discs I was listening to. I was, like, OK, I’m impressed. But I’m not aroused. So you can make chord changes sit up, roll over and swim across a pond. But my question is the same one Lester Young asked long ago, “Can you sing a song?” I’ll throw another one out there: Can you handle a groove?

Maybe that’s why, even in a better-than-average year for product, I was drawn to those albums that gave me a bit more of what Marsalis describes as “physical” or “visceral” pleasure. I admit that in Larkin’s famous tautology, I still lean a little more towards intelligence-without-beat over beat-without-intelligence. But most of what I choose to venerate this year came close to achieving a balance between the two. The needle’s still stuck at the low end as far as jazz music’s presence in the marketplace is concerned. But maybe some of these will help nudge it a little higher and attract more people who search the clouds, or Cloud, for sounds that both please and challenge. Baby steps, I suppose; dance steps, I hope.

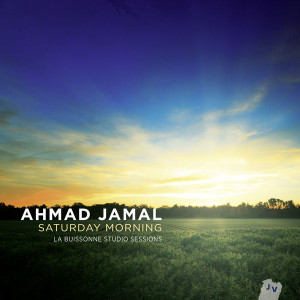

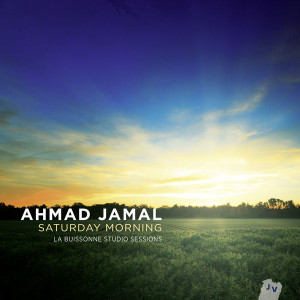

1.) Ahmad Jamal, “Saturday Morning” (Jazzbook) – You’re Ahmad Jamal and life right now couldn’t be more satisfying. You’ve outlasted almost all the pianists you’ve influenced since the 1950s who, fairly or not, received more critical approbation than you. You’ve also outlasted most of those critics who either demeaned or second-guessed your popularity and, in any case, never gave you the degree of respect you’ve received from audiences and fellow musicians. In the meantime, you’ve been putting out immaculately crafted recorded product for at least the last three decades. And at 83 years old, you’re playing with even greater vitality, invention and polish, submitting (for our approval) one of the crown jewels of your long career: A sweet-swinging session recorded at the Studio La Buissonne with the attentive support of bassist Reginald Veal and drummer Herlin Riley. As always, your trio keeps time like a handcrafted wristwatch. What broadens the package is the sparkling variety of tempo and mode. You seem even more engaged by the material, even with such familiar should-have-been-classics-long-ago as “The Line.” And though yours is the last such unit that would need extra percussion, the contributions of Manolo Badrena are seamlessly wired into your rhythm machine. You’re Ahmad Jamal and we’re just about as satisfied with your life right now as you are. (Thank you, Jimmy Cannon and may your own termite artistry soon be rediscovered.)

2.) Steve Coleman & Five Elements, “Functional Arrhythmias” (Pi) –And speaking of rhythm machines…First, though, a confession: Over the three or four decades alto saxophonist/composer Steve Coleman’s M-Base movement has been around, I could never cozy up to it; especially when it seemed intent on fashioning a kind of cerebral funk, as I prefer my funk to be pure and uncut. GIVE IT UP, PEOPLE, FOR BOOTSY’S RUBBER BAAAAAANNNND!!!! But I digress…If Coleman’s aesthetic principles have led to this ultra-sophisticated and fearsomely versatile aggregation of bassist Anthony Tidd, drummer Sean Rickman, guitarist Miles Okazaki and trumpeter Jonathan Finlayson, then I need to rethink, if not revoke, my earlier skepticism. As the titles of both the disc and its contents (e.g. “Sinews”, “Cerebrum Crossover”, “Cardiovascular”) imply, the intent here is to strike a polyrhythmic, harmonically complex connection with human physiology. It’s a smart idea (inspired, as Coleman says, by the example of drummer Milford Graves). But the intelligence behind the concept isn’t as conspicuous as its vigorous application. The band members are locked into each other’s frequencies and their interaction glides, strides, twists and meshes in the same manner as an abstract painting or modern dance piece. Coleman and Finlayson’s front-line conversations have a riveting yin-yang quality that places them at or near the high-end spectrum of such similar sax-horn confabs as Bird and Diz, Trane and Miles and Coleman’s namesake (if not relative) Ornette and Don Cherry. This disc has all the brains, and then some, of Coleman’s body-of-work. But it’s also got an unexpected surplus of — well, you know – heart.

3.) Darcy James Argue’s Secret Society, “Brooklyn Babylon” (New Amsterdam) – Having spent twenty thrilling years inhabiting the Beautiful Borough as it made the awkward, irrepressible leap from hipster incubator to Promised Land, I can testify that one of the many things that fascinate even the most casual Brooklyn bystander is the ongoing tension between its gilded skyscraping aspirations and its wait-till-next-year past lives. This 17-part suite for an 18-piece orchestra conflates Brooklyn’s past, present and (potential) future into what amounts to a steampunk fantasy novel of the mind. Argue’s epic tells the story of a master carpenter named Lev who, in a dystopian future (or alternate present), is commissioned to build a carousel atop a tower whose immensity could obliterate whatever‘s left of Brooklyn’s old-soul romance. The music aims as high as that mythical tower and you can feel yourself ascending on its surging waves of energy. But the suite doesn’t just go up; it spreads out to encompass different cultures from Eastern Europe to Latin America to the Middle East, keeping a fingertip or two on all-American swing and/or rock. You could follow Argue’s story or project one of your own upon its volatile contours. As with the only science fiction that matters, “Brooklyn Babylon” is lavishly hypothetical, strangely familiar and recognizably human in the grandest and grubbiest terms.

4.) Etienne Charles, “Creole Soul” (Culture Shock) – Jazz’s grow-or-die imperative has found its most gratifying adherents among 30-and-under musicians willing to use what they’ve learned of the music’s basics as springboards to more adventurous or exotic compounds. Charles, who just turned 30 this year, is a Trinidad-born trumpeter who received much of his education at Florida State and Juilliard and was inspired by the examples set at both institutions respectively by Marcus Roberts and Wynton Marsalis in re-energizing the music’s mainstream traditions. He retains some of Marsalis’ sound in his horn. But it’s the multicultural, polyrhythmic setting of this zesty, spicy gumbo that makes Charles’ music sound like exactly no one else’s. With a formidable array of young instrumentalists and percussionists as backup, Charles immerses himself in the varied strains of Caribbean pop – reggae, mambo, conga, even Gulf Coast R&B – to put together an mélange of electro-boogie, calypso and funk. Traditionalists can growl, snap and dismiss it all as “slick” pop. But the music they cherish has a far better chance for long-term survival with a sensibility willing to invite Monk (“Green Chimneys”), Marley (“Turn Your Lights Down Low”) and Bo Diddley (“You Don’t Love Me”) to the same house party and give each of them the respect and elbowroom they deserve. And, by the way, he also serves up melodies that stick to your head like Post-It notes reminding you what music is for.

5.) David Weiss, “Endangered Species: The Music of Wayne Shorter” (Motema) –Weiss, who also holds down a trumpeter’s chair here, leads a 12-piece murderer’s row of first-rank instrumentalists that includes trombonist Steve Davis, trumpeter Jeremy Pelt, saxophonists Ravi Coltrane and Tim Green, drummer E.J. Strickland and the incomparable pianist Geri Allen in celebrating the legacy and (though recorded live a year earlier at Dizzy’s Club Coca-Cola) 80th birthday of the Greatest Living Jazz Composer. They do not come to merely pay homage. That would be too much like church and the guy they’re honoring is far from finished. (See below.) Weiss instead leads his cadre on a reconnaissance mission probing the less-heralded (as in least-covered) pieces of the Shorter oeuvre as a means of illuminating its orchestral possibilities. The recital opens your eyes from the jump with “Nellie Bly,” which the always-surprising Mr. Weird wrote very early in his career when he was sitting in Maynard Ferguson’s reed section and now comes across as one of the more ornately conceived barn-burners ever lit. Even the most familiar of these selections, the inscrutably haunting ballad “Fall,” is given a rich, harmonically-layered treatment that inspires glistening fire-and-ice variations from Allen, Coltrane and, especially, Pelt. As widely acknowledged as Shorter’s writing brilliance has been over generations, it takes a classic setting such as this to reaffirm both the sturdiness and suppleness of Shorter’s melodies e.g., they endure and you can do almost anything you want with them.

6.) Matthew Shipp, “Piano Sutras” (Thirsty Ear) – If progressive jazz pianists carried the same renegade credibility in pop culture as heavy-metal rock guitarists, Matthew Shipp would be a biker’s tattoo by now. Twenty-something years is a long time to be an Angry Young Man. But the customary rules don’t apply to Shipp, who at age 53 can still wield a thorny club with swaggering panache, both on- and off-stage. His jazz-outlaw persona packs dual reserves of intensity and insolence; the latter, especially, gets him noticed in jazz circles when it’s directed at such elder statesmen as Shorter, Herbie Hancock and Keith Jarrett – the latter of whom could, ironically enough, match Shipp on whatever Mr. Cranky meter that’s available. For whatever it’s worth, I think Shipp’s uncompromising, mostly unsung insurgency gives him better reason to complain than Jarrett. He even released a “Greatest Hits” compilation earlier this year that made an impassioned what-the-eff-more-do-I-have-to-do case for his artistry. Still, this solo recital, meditative, prickly and ingenious, is an even more persuasive brief on Shipp’s behalf. It literally stomps, like the step-master of an unruly fraternity, to its own beat, piling dense tone clusters and weaving thick harmonic passages into eccentric, arresting patterns. On such pieces as “Cosmic Shuffle” and “Uncreated Light,” Shipp indulges his combative impulses before giving way to lyrical rumination. Though he may seem at times to be an unrepentant churl, Shipp’s “Sutras” remind listeners that, whatever hard things he may have to say, or play, at a given moment, he’s not inclined to stay mad – or stay anything else – for very long. (I bet he’s still happy, though, that I ranked this disc ahead of the next one.)

7.) Wayne Shorter Quintet, “Without a Net” (Blue Note) –As I said (maybe) earlier this year, the more I’ve listen to it, the deeper its mysteries grow; almost to the point of making me wonder whether there’s anything more to this group’s colloquies than mysteries for their own sake. Then, I try to tell myself what Shorter, in his way, is telling everybody else: that questions and answers are often the same thing. And I’ll go, yes, but…This incessant give-and-take between my ears is why “Without a Net,” for all its insistence on keeping secrets, stays on this list, no matter what. Give me another month or two and it’ll likely be back in the top five, but for the moment….

8.) The Claudia Quintet, “September” (Cuneiform) – Because I am an easy mark for crafty historical gimmicks, I was piped aboard this vessel by a number called “September 29th, 1936: ‘Me Warn You’,” in which the voice of FDR, sarcastically chiding his Republican fat-cat opposition for their empty promises of out-dealing the New Deal, is carved up, sampled, mixed, mimicked and harmonized with throughout by this eclectic chamber ensemble led by percussionist John Hollenbeck and featuring Chris Speed on reeds, Matt Moran on vibes, Red Wierenga on accordion and either Drew Gress or Chris Tordini on bass. Once you get past the wonder of hearing instrumental correlatives to Roosevelt’s memorable pipes and recognize the sly contemporary references being made by this juxtaposition, you start to wonder if the joke is being carried a little too far – until, about seven minutes in, when the group, collectively and individually, starts laying down its own cheeky variations on the president’s joke. This open-ended interplay typifies the rest of the album – a series of sound mosaics and tone poems devoted to the month that Hollenbeck prefers to use as time for reflection and contemplation. There’s a witty birthday salute to the unavoidable Mr. Shorter (“September 9th Wayne Phases”), a deep-dyed autumnal ballad (“September 25th Somber Blanket”) and, inevitably, a 9/11 piece (“September 12th Coping Song”) that closes the disc on with introspection that never becomes maudlin. It’s taken me longer than it probably should to have climbed aboard Claudia’s bandwagon and I’m still not sure why this particular one did the trick. But I plan to check back with them.

9.) Chucho Valdes, “Border Free” (Jazz Village) – I hope he wont take this the wrong way, but it must be said up-front: This man is a beast, a monster, an unstoppable force-of-nature – and, to be sure, a supreme virtuoso. But his is the kind of virtuosity that, rather than swooping down from thin air, blows the doors open to his listeners, making them run en masse towards him and scream for more. (Just listen to the first five minutes of “Congadanza” and you’ll know exactly what I mean. The last four are pretty “wow”, too.) Valdes is also a paragon among 70-something artists who seem to be gaining in raw power and messianic force with age. He and his Afro-Cuban Jazz Messengers aren’t just wearing down the all-but-fragmented barriers between hard bop and Latin jazz; they’re also expanding rhythmic horizons towards Native American (“Afro-Comanche”) and Andalusian (“Abdel”) sources of inspiration. He also takes time out to honor both his pianist father (“Bebo”) and his late mother (“Pilar”) in ways that make his Cuban homeland vivid and stirring. OK, so he gets a little carried away at times with the occasional Rachmaninoff reference and melodramatic flourish. So long as you can still keep up with the stories, what do they matter?

10.) Gerry Gibbs, Kenny Barron, Ron Carter, “Gerry Gibbs Thrasher Dream Trio” (Whaling City Sound) – If I had Barron, a grandmaster of jazz piano, and Carter, the greatest bassist alive, at my disposal, I bet even I could complete a dream trio with a frying pan, a crockpot and a pair of wooden spoons. But Gibbs, who’s been following in his vibraphonist father Terry’s footsteps by leading his own big band, brings his own aggressive sound, far-reaching chops and orchestrator’s instincts to this session, giving these two demigods a wide-open frame for their immense resources to roam like wolves. The result is a surprising rarity: a piano trio album delivering music with the heft and momentum of a larger ensemble, thanks mostly to the prodigious balance of power and flexibility coming through Gibbs’ trap set. Along with the usual stops (“Epistrophy,” “Impressions,”), the trio shines new light on works by McCoy Tyner (“When I Dream”) and Herbie Hancock (“The Eye of the Hurricane,” “Tell Me a Bedtime Story”). The biggest revelations, however, come from the pop book: that old mid-1960s warhorse, “The Shadow of Your Smile,” Stevie Wonder’s “Don’t You Worry ‘Bout a Thing” and, most especially “Promises, Promises,” whose sleek mounting and seamless arrangement here showcase Carter and Barron’s mastery of tempo and changes while delivering what may be the most effective jazz take yet on a Burt Bacharach tune.

HONORABLE MENTION: Maria Schneider & Dawn Upshaw, “Winter Morning Walks” (ArtistShare) Marc Cary, “For the Love of Abbey” (Motema) Charles Lloyd & Jason Moran, “Hagar’s Song” (ECM) Joe Lovano UsFive, “Cross Culture” (Blue Note) Geri Allen, “Grand River Crossings” (Motema) Bill Frisell, “Big Sur” (Okeh) Carla Bley, Andy Sheppard, Steve Swallow, “Trios” (ECM) Wadada Leo Smith & Tumo, “Occupy the World” (Tum) Ben Allison, “The Stars Look Very Different Today” (Sonic Camera) Rudresh Mahanthappa, “Gamak” (ACT) Fred Hersch & Julian Lage, “Free Flying” (Palmetto) Art Pepper, “Unreleased Art, Vol. VIII: Live at the Winery, September 6, 1976” (Widow’s Taste) Matt Mitchell, “Fiction” (Pi)

BEST NEW ARTIST: Jonathan Finlayson & Sicilian Defense, “Moment & the Message” (Pi)

BEST VOCALIST: Gregory Porter, “Liquid Spirit” (Blue Note) HONORABLE MENTION: Youn Sun Nah, “Lento” (ACT)

BEST LATIN ALBUM: “Creole Soul” HONORABLE MENTION: “Border-Free”

October 9th, 2013 — TV reviews

So I watched last night’s PBS Frontline report on brain damage in the NFL and learned little that I hadn’t known before – except that things may be even worse than we now know, and that the professional football oligarchs are even less willing to deal with the ramifications.

Kids make up the relatively undiscovered country for those probing the causes and effects of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), which afflicts hundreds, perhaps thousands of those who’ve played American tackle football. The frightening evidence emerging towards the end of “League of Denial: The NFL’s Concussion Crisis” implies that even those who haven’t played football for very long or been hit in the head very hard are susceptible to CTE. The program’s producers and reporters are scrupulous enough to say such research is preliminary. Still, the idea of high school players becoming as suicidal or disoriented by CTE as veteran lineman who have battered each other senseless for decades makes you almost as queasy as watching human brains delivered and unpacked at laboratories for poking and gazing.

As noted, most of the details in “League of Denial” have been covered before, notably by HBO’s Real Sports with Bryant Gumbel, ESPN’s Outside the Lines, the recently-released documentary, The United States of Football and the New York Times’ Alan Schwartz (among those interviewed), who’s been growling and snapping at a recalcitrant NFL for almost two decades about the mounting evidence of CTE-related illnesses and deaths among retired and active players. As its title suggests, “League of Denial’s” real story isn’t about those who have suffered the effects of CTE, but the elaborate degrees to which the NFL has resorted to Cover Its Ass (CIA) against the revelations dislodged by Schwartz and others. That the documentary was aired on PBS and not on ESPN, which was pressured by the league to withdraw from a partnership with Frontline on the program, only buttresses the points put forth by reporters Jim Gilmore, Steve Fainaru and Mark Fainaru-Wada. You cringe more in anger than dread over how the NFL tried to discredit, sometimes to the point of humiliation, doctors and researchers trying to counter the arguments made by the league’s own research team – whose own findings were, saying the least, dubious, almost irresponsibly dismissive of any alarming trend.

But, as somebody somewhere once said, scrape an arrogant bully and you’ll soon reveal the squirming coward within. The NFL is wily enough to equivocate its way towards “improving safety” and other CIA gestures; it’s also smart enough to fear the consequences of inaction. The $765 million settlement the league made with players over concussion issues may buy enough time to figure out what to do next, especially since this furor has dealt mostly with long-term effects.

So far, anyway. But still…

I wonder if NFL commissioner Roger Goodell knows enough about boxing history to acknowledge what happened – or started to happen – to that sport on the night of March 24, 1962 when Benny Paret and Emile Griffith met again to fight for the welterweight championship. The fight was broadcast live on the ABC network back in a time when Friday Night Fights was as much of an American sports TV ritual as Sunday Night Football is now. The story of that ill-fated match and its lingering, dismal aftermath has been well and fully chronicled in a haunting 2005 documentary, Ring of Fire: The Emile Griffith Story. For a long time, the story was simple enough: Paret taunted Griffith in the days leading up to their third and final bout as being a maricon, a derisive word for homosexual. Since then, others have speculated that it was the beatings Paret, as incumbent champion, had taken in his previous title defenses that made him more vulnerable to what would happen. Whatever the case, one thing is certain: During Round 12, before millions of viewers in addition to hundreds at Madison Square Garden, Paret somehow got tangled in the ropes and Griffith unleashed a vicious flurry of 29 successive punches, mostly to Paret’s head. Paret slumped to floor and never regained consciousness. He died almost ten days later. (The moment, horrific as it was, summoned the very best of Norman Mailer’s prose. I have had journalism students whose resistance to Mailer was worn down by his descriptive powers here.)

Among the myriad effects of that fight, the most immediate was the end of live boxing broadcasts on network television. A lot of people thought boxing itself would, or should end, too, especially after another fighter, Davey Moore, died in the ring a year later. But boxing didn’t quite die; indeed, it subsequently enjoyed a majestic decade-and-a-half dominated by such larger-than-life personalities as Ali, Frazier, Foreman, Leonard, Hearns and others stoking its momentum. It wasn’t until people saw what boxing had done to Ali that the once mighty and singular stature boxing once enjoyed in American life diminished to its more-or-less cultish following. The fight aficionados whom I know, love and respect may disagree with this assessment. But not even they can deny that Benny Paret’s death marked the beginning of the end of…something.

Imagine the nightmares Goodell must have these days about something similarly shocking happening to a football player on the field, especially in a nationally televised game. We’ve already seen career-ending broken legs and life-long paralyzing injuries transmitted through our home-entertainment centers. How could you not wonder about the percentages for or against a fatal collision with players getting bigger, faster and stronger? How much padding or protection is enough? Or, even, too much? And if an on-field death from tackling does happen, what next? Well, for starters, there will be howls for football’s banishment as loud as those seeking to outlaw boxing in the wake of Paret’s death. Football won’t end. There are as many waves of people who want and need to play the game now as there were generations of hungry young boxers waiting in 1962 for their Main Event. But what will happen is the slow erosion of football’s romantic allure, its cozy, family-friendly aura of escapist high-wire adventure. The mystique, far more than the muscle, is what’s been raking in billions for the NFL since that twilight evening in December, 1958 when Johnny Unitas drove the Baltimore Colts offense on Yankee Stadium’s turf like a white-and-blue T-Bird to shatter a post-regulation tie. I’ll miss that mystique, but what could be put in its place is the kind of rakish, outlaw abandon once associated with pro football in its grayer, dustier days. Bye-bye, Pete Rozelle. Welcome back, Johnny Blood.

I’m still hoping it wont come to that. I think even the people behind “League of Denial” hope that, too. We’d all be damned fools to think it couldn’t.

September 10th, 2013 — TV reviews

Maybe if Jane Fonda had been allowed to channel her third husband when the series started, as opposed to its last couple weeks, more people would say nice things about The Newsroom. As it is, Aaron Sorkin’s unwieldy hybrid of screwball workplace comedy and tag-team poly-sci seminar will wind up its second season this week so distant from the zeitgeist that even people who like the show don’t talk about it much. And when they have lately, it’s to express some degree of disappointment with it, e.g. it’s gotten too slow, too solemn or too much like regular TV, only with more profanity, sex and drugs (and far less of the last two than in Season One). The haters, though yielding a tad more slack to Season Two, say pretty much what they said a year ago – and they keep finding new ways to hate what they see, even though they keep watching anyway.

It’s too bad the crowd has receded. Because after an erratic, even disquieting start, The Newsroom’s second season has brought forth some of the finest work released under Sorkin’s name since The Social Network. And I’m thisclose to declaring this year’s seventh episode, “Red Team III”, better than most of The West Wing during Sorkin’s four-year tenure as executive producer. Directed by Anthony Hemingway (Red Tails, The Wire), “Red Team III” climaxed the season’s running story in which producers, staff and anchors for the mythical Atlantis Cable Network are being deposed by the network’s attorney (Marcia Gay Harden) to prep for what’s been hyped as a potentially devastating lawsuit against ACN; all having to do with an American military operation code-named “Genoa”, which the network reported had deployed chemical weapons against Pakistani civilians. Though second- and third-guessing elements of the report assembled by an ambitious producer (Hamish Linklater), the ACN’s Big Three of anchor Will McAvoy (Jeff Daniels), news director Charlie Skinner (Sam Waterston) and producer Mackenzie McHale (Emily Mortimer) sign off on the story, which nets them their biggest ratings haul in years – and turns out to be completely untrue.

It’s only in this episode that the plaintiff in the lawsuit is disclosed as the report’s justly-fired-and-discredited producer, who claims he’s being scapegoated for what’s labeled “institutional failure.” Apparently, this also encompasses all the mostly embarrassing stuff that’s taken place throughout the year, much of it courtesy of whatever’s meant by “new media”: the on-line nude photos of ACN’s resident brainiac Sloan Stevens (Olivia Munn); the ongoing fallout from the YouTube-d video of a tour bus meltdown by staffer Maggie Jordan (Allison Pill) and other events whose deus ex machina value for Sorkin fit snugly with his show’s not-so-subtle disdain for all things digital, especially the Twitter-verse.

And yes, I know that it’s probably redundant in many minds to place “not-so-subtle” and Aaron Sorkin’s name in the same sentence. In the words of Anthony Lane, Sorkin “raises hectoring to the level of an art.” (One adds with due haste that Lane’s words weren’t applied to Sorkin, but to Jimmy McGovern, a British playwright, who, as with Sorkin, found his greatest notoriety in television while also establishing a reputation in theatrical film.) You have to be in the mood for hectoring and I guess I was in the mood for it last summer when The Newsroom’s first season tore through the TV set like a squall — accompanied, as squalls are, by intervals of humidity. Sorkin’s alternate media history of 2010 was pissed off in general about the same things I was pissed off about during the presidential election summer; which was why, despite the contrary opinions of critics I respect, I bought the whole grandiloquent package. If Sorkin wanted to rant about the decline of civility in public discourse, the cheapening of what used to be considered “news value” and the manner in which presenting facts in a reasonable, even balanced manner could be construed by right-wing fanatics as “slanted,” I was OK with it – up to a point.

That point converged primarily upon women. With the possible exception of Munn’s Sloan (who makes wonky social awkwardness a variable of imperturbable hotness), just about all the principal women characters in The Newsroom’s first season were hyperbolic, dysfunctional, manipulative or some annoying compound of the three. The exceptions were the near-anonymous support staff members with names like Tess (Margaret Watson), Tamara (Wynn Everett) and Kendra (Adina Porter), all of whom seemed composed, competent and fretless. We were kept in the dark about their private lives and I wish the same were true with everybody else in the cast, especially Maggie, her ex-boyfriend Don Keefer (Thomas Sadoski) and her would-be boyfriend Jim Harper (John Gallagher Jr.), who now has a thing for on-line political reporter Hallie Shea (Grace Gummer). Do I like these people? Mostly, I guess. Do I care whether any of them hook up? I do not. I prefer they all put their heads down and get to work the way Tess, Tamara and the others do. And while I understand Will and Mac’s relationship to be the series’ linchpin, I’m so indifferent to their will-they-or-wont-they-reconcile-after-their-bitter-breakup subplot that I’d now rather they never ever get back together…which for all I know may well be how this second season pans out.

What did pan out for certain this season – eventually – is that people on the show were concentrating much more on their work. Operation Genoa may have ruined ACN’s credibility. But it released The Newsroom from its frantic obligation to reboot recent history; just as well, too, judging from the peculiarly ambivalent way the show approached the Occupy Wall Street movement earlier this season. In the process, the women were generally smarter and stronger than last season. Harden’s droll, satiny portrayal of the company attorney provided one of Season Two’s recurring pleasures. Gummer’s character confuses me a little, but I thought her poker-faced autonomy was exactly what Jim had coming to him. I also wanted more of Constance Zimmer’s spiky communications director for the Romney campaign, thinking that if Sorkin insists on finding romance for McAvoy (a.k.a. Hamlet the News Lug), she’d be what government jargon would insist on labeling a “viable option.”

But the most gratifying change from last year has come from Mortimer. Her Mac McHale blossomed this season from a welter of mannerisms and nervous tics into a woman who, when she slows her roll long enough to stare at, or down, a situation, lets you see the rueful wisdom earned with her wounds. Sorkin’s scripts still make her steer cars into curbside garbage containers and induce gibbering noises from her whenever she thinks about the used-to-be that was Will-and-her. But even before she sussed out the fatal flaw in the Genoa story, Mac was showing more self-possession under stress.

I think both she and the show reached a turning point in this season’s fifth episode when she scolds a gay Rutgers student about to come out to his parents on the air during a segment of Will’s show about the Tyler Clementi suicide. One senses that it’s Sorkin’s voice one hears when she’s chiding the student for “bathing in the reflected tragedy” of someone who killed himself because his privacy was violated.

(Sorkin did a lot of this mouthpiece stuff throughout the first season and for much of this one. I admit it. It got old for me, too.)

“I just wanted a way of coming out to my parents without being in the same room,” the student then tells Mac.

“Well, good luck with that,” she says, then, trying to reassure him. “It gets better.”

“How would you know?” he replies.

“I guess I wouldn’t,” she concedes.

Which says to me that, at last, The Newsroom is thinking through things before, and maybe even instead of, emptying its rounds. I wish cable news and new media in general would follow this example.

And if The Newsroom continues to deepen its inquiry into the post-Millennial news business, I hope it hits harder than it has so far upon the whole notion of a 24-hour news cycle, which to my mind has done far greater damage to journalism than Twitter feeds. Whatever happens, the show still likely wont get more traction and attention than the last few episodes of Breaking Bad. I get it. I really do. There hasn’t been a single feature film I’ve seen this year that compares with what I’ve seen so far of Breaking Bad’s last mile. But somehow, it’s become so relatively unfashionable to like The Newsroom that I can see it becoming relatively fashionable again. Just as long as everybody on the show keeps their minds more focused on the news beyond their room.

September 4th, 2013 — movie reviews

If you were to ask me which of this receding summer’s movies I’d be happy to see again tomorrow, next week or even a year or two from now, they would be In a World… and Frances Ha. I’m not trying to be trendy here, even though any day now I’m expecting some renegade financial pundit to suggest that George Lucas and Steven Spielberg are on to something and that historians may regard the summer of 2013 as the beginning of the end of the popcorn tent pole era (or whatever other euphemism suits you.) I doubt the all-powerful global market has exhausted its fascination with action-hero extravaganzas and neither have I. But the omnipresence of big, noisy Hollywood franchises has aroused in me – and I suspect many more – an appetite for the smaller stuff. And I’m not in any way suggesting that “small” equals “good” or that “big” equals “mediocre” or even “predictable” or….

Never mind. Just go see In a World… while it’s still hanging around. (And it is, amazingly enough.) It made me happy in so many ways, not least for raising writer-director-star Lake Bell’s profile – and about time! I’ve been a fan of hers ever since I saw her pilfer the otherwise dreary 2007 romantic comedy, Over Her Dead Body, out from under Eva Longoria, whose TV stardom gave her top billing in what was essentially a supporting role as a bitchy ghost trying to keep Bell’s character away from the ghost’s ex-fiancée (Paul Rudd). Bell’s lanky grace and astute timing outclassed everything else in the movie, except, maybe, Rudd, with whom she was so perfectly matched that you wished they could have been airlifted to a better story, if not an alternate universe.

It could only be in that time continuum that Bell’s impressive showing would lead to bigger roles afterward. But my review of Over Her Dead Body lamented that a wry, incisive talent such as Bell’s would have a tough time finding Hollywood comedies sophisticated enough to appreciate, even showcase it. Inevitably, as a kind of consolation prize, she got to do support work in such big-studio rom-coms as 2008’s What Happens In Vegas, 2009’s It’s Complicated and 2010’s No Strings Attached. Each time, more than a few of my critical brethren were moved to remark that Bell was funnier, more authentically human than most of the pre-cooked star turns in those movies. I would tell them if they wanted to see Bell really show her stuff, they should turn to where most of our best actors are these days: Television, where she was Doctor Cat Black on the very dark, very coarse and (thus) very funny Adult Swim series, Children’s Hospital.

As for the movies, Bell was likely smart enough to realize that the only way she was going to get a big, decent role in a romantic comedy was to build one of her own. Hence, In a World…, which, though it’s ostensibly about professional voice-over artists, gently, but firmly jabs at hidebound Hollywood attitudes towards women – and, implicitly, anybody else who doesn’t fit its generic career cubbyholes; just as In a World… doesn’t fit any of the accepted variables for contemporary American comedies. It doesn’t shout, pander or broadly contrive things. It has people you enjoy spending time with, even at their worst. And it has a central character who, though an adorable mess, is also capable of the kind of inspired, attentive improvisation that keeps our best jazz musicians working and hoping for the best.

Briefly: Bell’s Carol is part of the inner circle of Los Angeles-based voice-over specialists fiercely competing for gigs to intone promotional copy for movie trailers. Their demigod (and the movie’s guiding spirit) is the late Don LaFontaine, from whose all-but-trademarked line, “In a world where…”, the movie derives its title. She comes by her profession from her father Sam, depicted here as being the closest voice-over professional in legendary stature to LaFontaine. Sam’s played with sauntering arrogance by A Serious Man’s Fred Melamed, who evokes a sexy-bear Phil Silvers bulked by gamma rays and self-centeredness. Carol’s curriculum vitae, saying the least, doesn’t glow in the dark as Sam’s does and Sam, re-married to a blonde (Alexandra Holden) who’s a deceptively ditzy contemporary of Carol and her sister Dani (Michaela Watkins), thinks that’s just the way the industry wants it. “I’m not sexist,” Sam insists, even though he’s the first to complain about women stealing men’s jobs when one of his friendly competitors (Ken Marino) loses a high-profile audition to some…girl. And yes, unknown to Sam or his friend, it’s Carol. This is one of a handful of misunderstandings zipping blithely through In a World… Not all of them have to do with Carol, Sam or even voice-overs, though at least one of them submits a delicate reminder that you can’t believe everything you hear.

I don’t want to get you guys too excited. Bell still has room to improve some of her staging and at least a couple of her visual transitions. But her greatest assets as an actor, her timing and her ear, are filtered into both her direction and her writing, the latter of which got its props at this year’s Sundance Film Festival. Anyway, I’m a sucker for movies that have an informed appreciation for their capacity for sound, as opposed to noise. . I’m an even bigger fool for funny women such as Bell who can not only hear the subtleties in other people’s voices, but in their personalities as well. There isn’t a malicious streak anywhere in this movie. And it says a lot about Bell’s generosity of spirit that the movie includes amusing cameos from both Longoria (playing herself in self-deprecatory mode and looking even better than usual because of it) and What Happens in Vegas’s Cameron Diaz (barely recognizable as an action heroine in a grainy faux trailer). I want to see In a World… again, not just because it’s such a pleasant, stealthily profound lark, but because I still can’t believe it’s out there. I mean, in This World, anyway.

August 27th, 2013 — movie reviews

As of this week, a half-century will have passed since the March on Washington took place. As of today, a black man is president of the United States and the number one movie in America is about a black man who spent most of his life as a White House butler. You’d have to be some manner of lunatic to claim this doesn’t show that things have changed mostly for the better since the summer of 1963. You’d also have the mind of a rock to assume that this means the game is over, the Dream is Reality and some other uptight ninny wont decide to stalk Forest Whitaker in an upscale grocery store again.

Whenever stuff such as the incident obliquely referred to above pokes into view, some fluffernutter in public office or on TV uses it as an opportunity to encourage bemused spectators to engage in a “conversation about race”; you know, as in: “Just talk amongst yourselves about this race stuff so that we can keep a dialogue going and somehow that dialogue will keep us from being embarrassed when more prejudiced people are caught in the act of being themselves, etc. etc. etc.”

Just so we’re clear: “Race” is, at best, an abstract concept. Abstractions, at best, make people uneasy because abstractions are difficult to grasp as tangible subjects for whatever it is we humans consider “conversation.” Huge abstractions, such as “peace,” “war” or “race,” aren’t topics for conversation so much as occasions for speaking, mostly in public forums such as legislative chambers, TV studios or glandular discharges on the Web, whether as status updates or blogs like this.

In other words: You don’t “talk” about “race.” You “speak” about it. When you “talk,” it’s mostly about your parents, your jobs, your kids; the stuff they learn (or don’t); the stuff you read (or misread). You “talk” about what you overhear, or pretend not to hear. You “talk” about the shabby way you’re treated in a checkout line, or on an airplane or during an otherwise normal workday. Then you “talk” about imagining such things happening to you. If whatever is meant by “race” never ever comes up in these conversations, then somebody’s either hiding or avoiding something because “race” is as unavoidable a subject in American life as it is a vacuous concept. And we’ve always been good at tabling the subject, if not the vacuousness, when it suits us.

That said, Paula Deen and George Zimmerman, along with the build-up to that aforementioned 50th anniversary celebration of the March have helped create an unusual spike in race-related interaction on and off the Internet this summer. So, for that matter, have two movies by African-American filmmakers, Lee Daniels’ The Butler and Ryan Coogler’s Fruitvale Station. Both have provided plenty of opportunities for “speaking” about race. Yet I’ve noticed that when people “talk” about these movies, they do so acknowledging or, at least, suspecting that there are deeper, more complicated aspects to identity and history than whatever shorthand is deployed by popular culture for “race” or even “class” distinction

Fruitvale Station and The Butler go for the gut more than the head in stimulating their responses. But I think both movies achieve their best effects in what they choose not to do to arouse their audiences’ emotions. In Coogler’s case, it’s his resistance to make his doomed protagonist Oscar Grant III (Michael B. Jordan) either a hapless victim or a sanctified martyr. He’s just a serial screw-up making a one-day-at-a-time effort not to leave messes behind wherever he goes. The slivers of hope that are weaved into the last 24 hours of Oscar’s life are made to seem almost as random or as arbitrary as the circumstances leading to his death You could wish or hope he could be more conscientious about the process. But he’s not you or me. He’s a person confronted moment-to-moment, like the rest of us, with options that don’t always reveal their likely outcomes. So when he’s shot to death at the movie’s eponymous BART station on New Year’s Eve 2008, it stuns us more deeply and intimately than it would if the movie were a more overt indictment of racism and police brutality. A symbol or a martyr wouldn’t leave us feeling as devastated at the end as does this movie’s persuasively human Oscar Grant, especially given Jordan’s thoughtful, composed rendering.

The movie’s tough-minded approach is likewise reflected in its portrayal of Oscar’s mother Wanda (Octavia Spencer), who comes across less as the long-suffering black matriarch of predominantly white imaginations and far more as a pragmatic working-class woman who is in constant negotiation with her own heart as to the best way of dealing with her son. Portent and shadow threaten to upend the movie’s levelheaded tone. But that tone wins out; the film’s soft-pedaled humanism maximizes the impact of Coogler’s penultimate blow, reminding everybody who sees the movie that making a sanctified abstraction out of real people like Oscar (and Trayvon Martin and many others like them) is as heinous a crime as what happened to them in the first place.

If Lee Daniels had made similar choices in directing 2009’s Precious: Based on the Novel “Push” by Sapphire, I might not have carried as many qualms about The Butler into the multiplex with me. I was one with the critics who believed that earlier movie to be yet another grim variation on Dem Black Pathology Blues that mainstream audiences have too often and for too long accepted as definitive, comprehensive proof of African American dysfunction. Daniels’s baroque curlicues and smudges (e.g. that Fellini-esque parody popping up on Precious’s TV set) didn’t mitigate the bleakness so much as help mark the whole enterprise as an overwrought extravagance, coated with sociological grease from somebody else’s skillet. I was even less inclined to give Daniels slack a year ago when he’d turned Pete Dexter’s best novel, The Paperboy, into another, even more sodden indulgence.

So I didn’t expect Lee Daniels’ The Butler (What is the huge hairy deal with this guy and titles?) to be a cool, dry model of artistic decorum and to that extent, it matched anticipation. This is one of those movies that starts off moist and stays that way throughout. Even the colors on the screen bleed into another the way they did in The Paperboy as if the whole movie were pre-soaked with salty tears. It’s an unwieldy farrago of elbow-nudging history lessons, domestic (in every sense of the word) tension, bell-ringing uplift, senseless violence and besieged nonviolence. (Question for further study: Which made you cringe more? The out-of-nowhere shooting death in the cotton field or the ascending levels of abuse visited upon the SNCC lunch-counter brigade?)

Still…while I might have wanted something far subtler, less overbearing than what Daniels has put forth here, I found myself giving in to The Butler’s old-school Hollywood storytelling. This is the kind of period melodrama where the periods pile into each other heedlessly and impulsively. Denying the primal power of the movie’s cluttered dioramas is pretending I wasn’t enraptured by any number of Warner Bros. or MGM biopics on the afternoon black-and-white TV sets of my childhood. The historian in me was all too aware of how Daniels’ movie conflated and in some cases blithely ignored the actual chronology of the events sweeping by Cecil Gaines (Forest Whitaker) and his family. But I believe The Butler’s main order of business is to convey emotional, rather than accurate, history. And it manages to do so without any lurid, excessive flourishes – that is, unless you count the flaccid caricatures of the First Families, which though not quite the alleged Saturday Night Live routines, aren’t terribly resonant either, save for Jane Fonda’s brief-but-effective depiction of Nancy Reagan as a brittle empress packing concealed paradoxes.

But do I mind commercial movies whose black characters are more fleshed-out and central to both theme and action than the white ones (as opposed to the reverse)? I’ll let you ponder that as I finally get around to talking about Oprah Winfrey’s surprisingly saucy and limber performance as Gloria Gaines, Cecil’s wife. As with Spencer’s Wanda, Winfrey’s Gloria appears poised to have a neon sign blinking, “long-suffering”, with her every on-camera appearance. But she turns out to be far too nuanced and complex to neatly embody such a cliché. She drinks too much, cheats on Cecil with Terrence Howard’s trifling next-door neighbor (who at least looks as if he earns a paycheck, too) and harbors deep-rooted, but inchoate resentments that not even Cecil’s devotion and achievement can dispel. Nevertheless, the narrative envelops sufficient time for the mercurial Gloria to grow out of, if not entirely overcome, her flashes of bitterness. Neither absolute paragons nor soapy contrivances, Cecil and Gloria seem more lifelike than the melodrama that surrounds them.

I hear some claim that such characterizations are only possible with an African American director or writer. I remain unconvinced, mostly because of the lingering memory of 1964’s Nothing But a Man, which, though directed by a white man (Michael Roemer) who co-wrote it with another (Robert M. Young), set a high standard for realistic, humane depiction of African Americans in love and trouble. And I’m a little bugged that Cecil’s resentful activist son Louis (David Oyewolo) does come across as something of a cliché; at least to those who may have forgotten that there were reasons why nonviolent activists like Louis got tired of turning the other cheek. And why oh why does the movie decide to transform Louis’s gentle, soft-spoken Movement girlfriend Carol (Yaya Alafia) into the sullen, Afro-headed demon of both white and black middle-class imaginings? “Low class bitch”? Really? That’s our takeaway from this beautiful young woman who had earlier strained so painfully hard to keep her resolve during the sit-ins? That’s a vulgarization I can’t easily forgive, no matter how many ambivalent feelings I may now have towards the Black Panthers and their fellow travelers.

Nevertheless, I’m glad to see The Butler get over for one reason above all others: For once, a Hollywood movie about black civil rights doesn’t have a white surrogate hero for whom African-American struggle exerts some manner of soulful transformation. Its box-office success (so far) has tempted pundits to believe that black American cinema may have at last achieved its crossover moment. Excuse me if I don’t join the choir on this one, because I’ve heard this tune many times before now. Maybe what can best be said about this summer of Fruitvale Station and The Butler was uttered fifty years ago this week in a speech better remembered for other phrases: It’s not an end. But a beginning.

August 14th, 2013 — movie reviews

I never knew before seeing Blue Jasmine that so many people in San Francisco talk as though they lived in Bensonhurst all their lives. Nor, for that matter, did I know there was anyone under the age of, say, 50, who at this point in our history needed to go to something called “computer school” as a step towards taking on-line interior decorating courses. Then again, I bet I could tell Woody Allen a lot of things he doesn’t seem to know from watching his latest movie; for instance, that living in Brooklyn these days isn’t such a comedown from living in Manhattan. I mean, has he even noticed what a two-bedroom-one-bath apartment now goes for in Park Slope? Or even Bed-Stuy?

I’m aware that I now sound like all the knee-jerk Woody bashers who love finding fault with everything he does, inflating their contrarian capital off a reputation that hasn’t been nearly as impregnable as it was in 1979. What I mostly find admirable about Woody Allen these days (and it’s no small thing) is his tenacity in stepping up to the plate every other year just to see if he connects — and how far he can take the ball, whether the critics or the public like it or not. Don’t like that metaphor? How about the old saw of throwing a pile of you-know-what against the wall to see what shape it makes? However you look at it, this is what Allen chooses to do with his life now and if what sometimes results from his habit can be as satisfying as Vicky Cristina Barcelona or as haphazardly diverting as Midnight in Paris, then I’m thinking there are far less salutary ways for a 77-year-old man to spend his time.

Blue Jasmine has been wildly hailed, even by a few habitual Woody bashers, as being one of his best. I wanted to agree, partly because I prefer to cheer Allen on, but mostly because of what’s been proclaimed the movie’s principal asset: Cate Blanchett, playing a lapsed socialite driven to a slow-motion breakdown by the fiscal and marital cheating of her ponzi-scheming husband (Alec Baldwin)., Blanchett borrows much of the Day-Glo manic intensity she brought to her legendary stage rendition of Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named Desire to make her Jasmine a moist, quivering tower of jolting mood swings and ruined dignity. You stare at her face the same way you can be hypnotized by a wall-sized relief map of the world. All that’s familiar about her is every bit as exotic and mysterious as the places you didn’t know existed. Though she’s more formidable a physical presence than anybody else on-screen, Jasmine still teeters on the edge of sanity like a china figurine on the ledge of a shelf. You just want to be able to keep her from shattering when a fresh trauma jostles the ground beneath her.

It was only after the movie was over and she’d succeeded in breaking down my emotional defenses that I began to wonder whether Blanchett’s virtuosity amounted to a thinking-person’s special effect; something to “ooh” and “aah” over as you’re watching it block out the relatively threadbare thinking that went into the rest of the movie. Once Blanchett’s spell had dissipated, I even began to wonder how clever it really was for Allen’s movie to crib from the Tennessee Williams playbook to evoke the present-day reverb from the post-Millennial bust. It may flatter the professional and amateur spectators in the house to notice how Chili (Bobby Cannavalle), the earthy, volatile fiancée of Jasmine’s sister Ginger (Sally Hawkins) does or, mostly, doesn’t resemble Blanche’s bête-noire Stanley Kowalski. But that’s a lot different from responding to him as a human being. Even when he’s crying, Chili’s more a narrative device than a person. And this in turn places every other character’s humanity, even Jasmine’s, in doubt.

I’m willing to entertain the possibility that the artificiality of Allen’s tactics may be his point; that crises make us all, either wittingly or not, helpless characters in melodramas scripted by somebody else. However awkward or unearned the San Francisco milieu seems here (even the creepy-crawly dentist Jasmine fends off seems like someone whose office would more likely be based on Montague Street in Brooklyn Heights), it’s drawn out Allen’s better technical instincts. His cameras get more moodiness out of Ginger’s cluttered apartment than a less-experienced filmmaker would have dared. But the discordances in the storytelling, including the ones cited at the start of this piece, detract from such graces. I’m still not sure what to make of Jasmine’s harrowing rant in front of Ginger’s children beyond being another occasion to be riveted by the chromatic map of Cate Blanchett’s face. I’m mesmerized by the spectacle while wondering what it’s doing there at that moment.

There’s another performance in Blue Jasmine that’s just as transformative, maybe more so, than Blanchett’s. It belongs to Andrew Dice Clay as Ginger’s ex-husband Augie, whose marriage and life fell apart from investing his own modest fortune into a ponzi scheme. In his relatively few scenes, Clay conveys all the conflicting emotions of helplessness, bewilderment and unfocused rage common among those of us living in the aftermath of the burst economic bubble. I never thought I’d say this about anything to do with Clay, but I would pay to see a whole movie about that guy and I could even imagine Woody Allen making it – that is, if he could burst through his own bubble and see how the world beyond the East End and the Upper East Side truly lives now.

July 26th, 2013 — movie reviews

The creepiest, most phantasmagorical movie I’ve seen this summer has no zombies, vampires, aliens or mutants. Unless, that is, you wished to apply any or all of the above to characterize Anwar Congo, the Indonesian gangster and wannabe moviemaker profiled in The Act of Killing, Joshua Oppenheimer’s true-life chronicle of how Congo tried to make a glorified cinematic re-enactment of his country’s mid-1960s massacre of thousands of men, women and children suspected of communism. This enterprisingly deadpan inquiry into the banality of evil has slithered its way into our season of sun-and-fun to announce that not only is fiction dead, but so is black (as in absurdist) comedy. Why even bother trying to outgun Nathaniel West when Real Life can hand off an acrid fungus of a storyline such as this?

It helps not only to have reality be so obliging, but to have the collective vanity of killers comply with Oppenheimer’s audacious request. Then again, what is viewed as atrocity almost everywhere else in the civilized world is still embraced as glory by many Indonesians, especially the far-right paramilitary group Permuda Panacasila whose members swarm around the edges of this saga like mean orange hornets. This cluster of baby martinets owes its existence, apparently, to Anwar Congo, who before the failed 1965 coup that led to the Suharto regime, dealt in black market movie tickets and other relatively petty thuggery. For two years, Congo led death squads throughout North Sumatra in a bloody purge of those suspected of being communists, including several hundred ethnic Chinese from whom he and his goons extorted money in lieu of death. Of the estimated half-million-to-a-million murdered throughout the country in 1965-66, Congo figures he personally killed roughly a thousand, mostly by garroting.