December 4th, 2014 — jazz reviews

A strange year, an exasperating year; maybe even an ominous one for jazz music’s already diminished stature in the marketplace. First this happened, followed closely by this. And then this came up and so did all the resulting cawing and cackling on the social media sites. When you add the very public, free-falling disgrace of the nation’s leading — or, at the very least, most famous — jazz devotee, you may as well shrink wrap and label 2014 as a bummer despite the varied finery listed below.

And I know what you saner, stoic ones are going to say: That a list such as mine, or anyone else’s, represents the best possible counterargument to the signifying-nothing that is sound-and-fury, on- or offline. Art doesn’t care what the Washington Post or New Yorker says or does – or mostly doesn’t. Art walks its own serene path through the fire towards high ground. Art is a ninja-warrior aristocrat with two layers of body armor and an unrelenting poker face. Art would assure me, in firm, modulated timbres, that just because some people think jazz stopped being cool doesn’t mean it has.

Knowing all that, however, doesn’t improve my end-of-the-year mood; one that can’t be quantified as good or bad, but is, all at once, restless, melancholy, somewhat manic and predominantly wary. All told, I’m just a little anxious to see what’s coming next – in jazz and everywhere else.

You ask: Dread or hope? I say: Turtles are cool.

1.) Ambrose Akinmusire, “The Imagined Savior is Far Easier To Paint” (Blue Note) – As with its illustrious Blue Note predecessors from fifty years ago, Akinmusire’s second effort for the label meshes with the subconscious fabric of its turbulent times without needing to be explicit in its content (except when it chooses to do so). Just as Donald Byrd’s “A New Perspective,” which brought this into the world, is still redolent of all that America was going through in the early sixties, so do the somber, mostly minor-key soundscapes in “The Imagined Savior…” reflect present-day sorrow, regret and barely-contained anger with thwarted possibilities. The anger breaks into full, unfettered view in the sepulchral “Rollcall for Those Absent” on which the voice of young Muna Blake, backed only by Akinmusire’s keyboard and Sam Harris’ Mellotron is heard reading the names of young black men shot to death by police, including Amadou Diallo and Trayvon Martin, whose names are intoned more than once. That more names could have been added to this roll since it was recorded only enhances the disc’s up-to-the-minute capital. Adding to this Tapestry of Now is “Our Basement (ed)”, written and sung by Becca Stevens, which is told from the perspective of a homeless man. What counters the ruminative gloom and anxiety of these and other pieces is the vigorous musicianship displayed by Akinmusire as both trumpeter and bandleader. In both capacities, he has a fluid command of phrase that comes across the way electricity would if you could hold it in your hands. Whether letting fly with his regular combo, including front-line partner Walter Smith on tenor sax, or blending with a string quartet, Akinmusire’s horn reaches for and often achieves attributes of the human voice, a quality that clearly marks him as one with all the greats on his instrument who preceded him. If you wonder (as my erstwhile colleague and friend A.O. Scott does) if there are artists who can speak directly and indirectly to the Way We Live Now, look in this corner of the room and get to know its dimensions. Be advised: They can only get bigger from here on.

2.) Allen Lowe, “Mulatto Radio: Field Recordings 1-4 (or: A Jew At Large in the Minstrel Diaspora”)(Constant Sorrow 101) – In the 32-page liner notes accompanying this package, which constitute some of the finest music criticism I’ve read all year, Lowe begins by talking about his “strange encounter” with fellow classicist/bandleader Wynton Marsalis, with whom he dared discuss “the modernist implications of minstrelsy,” which Marsalis pointedly refused to engage since he’s predisposed to regard hip-hop in general and ”Gangsta Rap” in particular as “neo-minstrelsy” catering to racial stereotypes. Which was far from the point that Lowe was attempting to make in the first place. In the six years since that brush-off, Lowe, a polymath who’s as incisive with his shtick as he is with his sax, dove headfirst into what some would consider the mongrelized, or creole-lized foundation of 20th century popular music where shotgun-shack juke joints and free-swinging black vernacular found communion with the tunesmiths piecing together their slick contraptions on Tin Pan Alley, or in the Brill Building. The result of Lowe’s restless search for a proper response to Marsalis is this four-disc omnibus of mostly home-cooked sessions (Lowe lives in Maine) in which several traditions – gutbucket, gospel, early New Orleans, ragtime, bebop, stride, avant-garde, nightclub swing, noir soundtrack, beat poetry and backwoods country – are probed, prodded and often pulled inside out (so to speak) with an eclectic array of musicians from saxophonist J.D. Allen, trumpeter Randy Sandke and clarinetist Ken Peplowski to saxophonist Noel Preminger, pianist Matthew Shipp and singer Dean Bowman. Along with other reeds, horns and rhythm players, there’s also a tuba (Christopher Meeder), a fellow musicologist (Lewis Porter) who plays wicked piano, alone or accompanied, and – of course, what else? – a novelist (Rick Moody). Even some of the titles of these pieces – “Jim Crow Variations”, “The Discreet Charm of the Underclass,” “When My Alarm Clock Rings on Central Park West” (Lowe’s variation of “When it’s Sleepy Time Down South”) – are provocative, mischievous throw-downs to whatever passes these days for dialogue about jazz. And after a year such as this, the prevailing conversation can use some spritzing and shaking-up. (Don’t try to get this through Amazon or I-Tunes. You’re better off ordering it this way.)

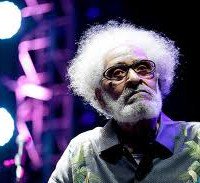

3.) Sonny Rollins, “Road Shows: Volume 3” (Okeh/Doxy)— I’m well aware that we who worship at the Altar of the Colossus often get carried away. My own effusions are tempered by what a fellow patron said about the GLTS (Greatest Living Tenor Saxophonist): that he’s a lot like Mickey Mantle because their strikeouts can be just as spectacular as their home runs. Still, you have to believe me when I tell you that this third installment of recent live Rollins feels richer, goes deeper and is altogether more rewarding than its predecessors. And I say this as somebody who tried, at first, to distract myself from its lure by doing…well I don’t remember exactly. But I do remember feeling my head swivel sharply upon hearing Rollins’ variations on “Someday I’ll Find You,” the album’s second track, from a 2006 performance in Toulouse. This Noel Coward ballad begs to be crooned in the grandest of tenor styles. Rollins never croons, at least not here. He asserts the theme while veering ever so modestly off its edges to let you know what’s coming as soon as he retrieves center stage from guitarist Bobby Broom. When it’s his turn to speak, Rollins slides into the first bars of the melody, pulling at its corners before he really gets to work somewhere around the third chorus. (Or is it the fourth? Never mind.) He’s clearing away open spaces for whatever direction he wants to go. At one point, he’s playing with the harmonies in the grand modernist manner of pulling them apart and rearranging them in different patters; maybe he’ll become fond of a riff and run with it to see if it opens still more territory, making just enough room for one of his licks to leap into the sky if only so he can find out where it lands. He’s trying to figure it all out as hard as we are. That’s why we’ve borne witness all these years: To collaborate in his process and share his potential surprise with what’s disclosed. There’s plenty more enlightenment to be found on these arias. And, jumping back a couple metaphors, there’s not a strikeout in the bunch.

4.) Kenny Barron & Dave Holland, “The Art of Conversation” (Blue Note) – Barron has proven to be such a compelling partner in previous recorded colloquies with Stan Getz, Charlie Haden and Regina Carter that it’s a wonder it’s taken this long for him to have a sustained sit-down with the indefatigable Mr. H. To say their meeting doesn’t disappoint would be understating matters to a felonious degree. They engage in an organic, mutually respectful flow of ideas and storylines with each man giving leeway to the other seemingly by intuition more than design. They hit all the lights on such standards as Parker’s “Segment” (which, for this occasion, should have worn its alternate title, “Diversity”), Monk’s “In Walked Bud” and, especially, Strayhorn’s “Daydream.” The revelations are more pronounced when it comes to each player’s compositions: Barron’s “Rain” opens vistas of lyrical expression for Holland while the latter’s “Dr. Do Right” craftily indulges Barron’s affinity for the Latin beat. I’m especially partial to the opening track, Holland’s “The Oracle,” because it is so reminiscent of one of my all-time favorite trio albums of the same name led by the late great Hank Jones and featuring Holland and the also-now-departed Billy Higgins. That album is out of print. This one more than compensates for its absence.

5.) Marc Ribot Trio, “Live at the Village Vanguard” (PI) – I have for decades challenged those who love hard rock, but hate progressive jazz to imagine, when listening to an outer-limits tenor sax solo, that there’s an electric guitar laying down the same pipe. I’ve urged jazz heads to do the reverse for heavy-metal speed runs. No takers at either end. But who’s going to listen to me anyway? Better that they should all listen to this, because when guitarist Ribot, drummer Chad Taylor and bassist Henry Grimes Go Outside as did John Coltrane (“Dearly Beloved,” “Sun Ship”) and Albert Ayler (“The Wizard,” “Bells”), they don’t merely make my point. They drive it home like a high-performance car going down on a steep hill at top speed. This unit’s been mining such territory for some time now and the revelations burn hotter within the hallowed confines of jazz’s Holy Dive. Oddly enough, though, it’s when Ribot and company do a 180 and apply their eclectic chops to light-footed, more conventional renditions of “Old Man River” and “I’m Confessin’ (That I Love You)” that they really seem to be taking chances; each man carefully spreading their range onto these chestnuts without unnecessary spillage. Their solicitousness within the body of each song gives greater magnitude to what they do outside the lines. Just to re-emphasize: Anything that’s done to amplify the enigmatic, yet persevering legacy of Grimes’ old boss Albert Ayler is worth the investment of energy; theirs, and yours.

6.) David Weiss, “When Words Fail” (Motema) – Most of the music here is so buoyant and luminous that you would never guess that the project is haunted by sadness and loss. Trumpeter Weiss, whose myriad activities include leadership of The Cookers, a septet formed in tribute to Freddie Hubbard, composed most of the pieces on this disc and writes in the liner notes of a full year of sudden, deepening tragedy beginning with the death of seven-year-old Ana Grace Marquez Greene, daughter of saxophonist Jimmy Greene, in the December, 2012 Sandy Hook School massacre. The father of the Motema label’s founder passed away during the ensuing year as did such jazz luminaries as Jim Hall, Donald Byrd, Mulgrew Miller, Butch Morris, George Duke and Cedar Walton. And just weeks after this session was completed, its bassist Dwayne Burro, died from pneumonia. The title track, named for the beginning of a Hans Christian Anderson quote that ends with “music speaks,” is dedicated to Burro while “Passage Into Eternity” was written with the Greene family in mind.. Here and elsewhere, you expect something somber and funereal, but instead find lively, propulsive small-group jazz that gives off warmth while staying resolutely cool. When the world keeps saying, “No,” music as joyfully rendered as this insists on saying, “Yes.”

7.) Mark Turner Quartet, “Lathe of Heaven” (ECM)— Somewhere in the alchemic Ursula K. Le Guin novel that gives this disc its title, there’s a quote from Victor Hugo that describes dreaming as “nothing other than the approach of an invisible reality.” As with the book, much of the music on this album, Turner’s first as a leader in 13 years, shifts time and space while somehow remaining self-contained and grounded. Not since the passing of Joe Henderson has there been a narrative artist on tenor saxophone such as Turner, who, as with Henderson, makes his statements through stealth, cunning and patience, his phrases cohering into shapes that are at once familiar and esoteric. He finds in trumpeter Avishai Cohen a worthy harmonic partner in thematic expression; Cohen bringing a fiery, full-bodied tone to compliment Turner’s cool, dry musings. The overall pace seems locked in neutral, the better to allow the mercurial front line to simulate invisible realities, though the rhythm section of bassist Joe Martin and, especially, drummer Marcus Gilmore execute throughout a slipstream swing compatible with weaving dreams. You couldn’t call this a comeback since Turner’s been quite busy in many venues and combos. But having him return out front, so to speak, affirms the hopes he inspired a decade-and-a-half ago as a tenor player skating to a softer drumbeat.

8.) Steve Lehman Octet, “Mise en Abime” (PI) – Though not packaged as such, Lehman’s latest series of experiments in sound mosaics represents a kind of deep-space 90th birthday party for Bud Powell, given that at least two of the tormented bop genius’s pieces, “Glass Enclosure” and “Parisian Thoroughfare,” are so drastically reinvented as to be barely recognizable, except for the angular dynamics Lehman applies to their abstract designs. Because his intellectual qualifications are part of Lehman’s hype, you’re tempted to think of his work as composer, arranger and altoist in purely cerebral terms. But given his all-star lineup of some of the brightest young players (trumpeter Jonathan Finlayson, trombonist Tim Albright, saxophonist Mark Shim vibraphonist Chris Dingman and drummer Tyshawn Sorey among others), Lehman has too much firepower at his disposal to leave listeners on ice, so to speak. He’s so creative in his harmonic combinations and electronic enhancements that I’m a little curious to see what he does in more specified contexts; Christmas, say, or 1940s rhythm-and-blues, or the Sun Ra Songbook.

9.) Matt Wilson Quartet with John Medeski, “Gathering Call” (Palmetto) – I’ll just repeat what I posted back in January since a whole lot’s happened since then: Hard bop, late-1960s/early 1970s vintage, played without apologies and with an open-hearted joie de vivre that can make even the hardest of hard-core progressives wonder why they ever thought the genre was old news. I suppose some would still think it old news, even if they liked it. But there’s nothing musty or creaky about Wilson’s easygoing command of the trap set in all situations or his group’s saucy renditions of such Ellingtonia as “Main Stem” or “You Dirty Dog.” The quartet also pays homage to the recently departed bassist Butch Warren by playing the latter’s “Barack Obama” with the delicacy, wonder and cautious optimism you suspect the composer had in mind as he wrote it. You’re happy for the leader, one of the perennial Good Guys in the jazz business, which in turn makes you hopeful for the business itself.

10.) The Microscopic Septet, “Manhattan Moonrise”(Cuneiform) — Where in their 1980s flowering they suggested, as a perspicacious observer put it, a “wedding band from Mars,” these wily retro sharpies now look on the inside-cover photos of this disc like a weathered, motley council of wizards from a Tolkien homage hiding out from Sauron on a band bus touring the Dakotas in the winter of 1939. Yet even with added snow in some of their membership’s facial hair, the Micros still sound airtight, agile and ready for anything co-founders Joel Forrester and Philip Johnston toss into their playpen, whether it’s a funk stomp a la Johnston’s “Obeying the Chemicals,” a Monk-ish pastiche from Forrester, “A Snapshot of the Soul” or the snap-brim eminently danceable swinger, also from Forrester, that gives the disc its title. Cards on the table, I’m at a loss to explain what “MM” by TMS is doing here since it doesn’t exactly break new ground either for the group or for its genre. But it’s a genre that they, and they alone, own: Microscopic Septet music at its most proficient, inquisitive and enjoyable. There may have been more significant and ambitious albums I heard or missed out on this year, but few that had as much trouble staying out of my machines as this. Long Live The Micros! And Long Live Jazz – whatever the heck that means!

HONORABLE MENTION: “Frank Kimbrough Quartet” (Palmetto); Tyshawn Sorey, “Alloy” (PI); Regina Carter, “Southern Comfort” (Masterworks ); Omer Avital, “New Song” (Motema); Ron Miles, “Circuit Rider” (Enja); Keith Jarrett & Charlie Haden, “Last Dance” (ECM); Randy Ingram, “Sky/Lift” (Sunnyside); Jason Jackson, “Inspiration” (Jack & Hill); Matthew Shipp, “I’ve Been To Many Places” (Thirsty Ear); Richard Galliano, “Sentimentale” (Resonance); Aaron Goldberg, “The Now” (Sunnyside).

BEST VOCAL ALBUM: Kendra Shank and John Stowell, “New York Conversations” (TCB)

BEST LATIN ALBUM: Arturo O’Farrill & the Afro-Latin Jazz

Orchestra, “The Offense of the Drum” (Motema)

BEST REISSUE: John Coltrane, “Offering: Live at Temple University” (Impulse!)

HONORABLE MENTION: Charles Lloyd, “Manhattan Stories” (Resonance)

September 7th, 2014 — on writing lit -- and unlit

It’s Sunday afternoon in the Universe and one of the appliances in my apartment insists on telling me that football is back. I change the channel to make it stop, but there are at least several other voices on other channels screaming the same thing. I flip over to Turner Classic Movies, which is showing Alfred Hitchcock’s Suspicion, and I could swear Cary Grant is telling Joan Fontaine that football is back. (Probably trying to make her crazy or paranoid or something…)

Once upon a time and not all that long ago, I would have been tingly and warm all over with the idea of football being back in my life. But I’m not feeling it so much now. Given what’s been happening with professional football over the last few years, I can’t imagine any sentient being with any degree of empathy embracing block-and-tackle football with unconditional love and abandon. Fear and loathing may be closer, but still too extreme in the other direction.

Speaking of fear and loathing: Hunter S. Thompson once characterized pro football as “a hip and private kind of vice to be into.” He was, at the time — 1974 – applying those words in the past tense since by that time, then-commissioner Pete Rozelle had already been referring to professional football as “The Product.” Thompson yearned for his version of the good old days of watching the 49ers play at decrepit Kezar Stadium in the mid-1960s “with 15 beers in a plastic cooler and a Dr. Grabow pipe filled with bad hash” while trying to avoid the mean drunks looking for reasons to punch somebody out, especially if the Niners were losing, as happened frequently in those days.

But even in those funkier times, pro football had already become a “Product” with competing brand names (a.k.a. NFL vs. AFL) willing themselves toward merger through the irresistible might of television revenues. The outlaw mystique that Thompson pined for was by 1965 already being nudged aside for what would, by the country’s Bicentennial 11 years hence, become a family-friendly franchise of hype and muscle itching to spread its influence beyond the USA’s boundaries.

The astonishing rise of the National Football League from sandlot outlier to global money machine remains the prevailing narrative of American-style football, a bedtime story the management class loves to hear before drifting back to sleep. You can tell, though, that even the NFL begins this season more nervous and self-conscious about its own standing.

What’s been called “the health crisis” is the biggest factor and the cumulative effect of concussions on pro players’ lifespans isn’t the half of it. (The league’s ham-handed attempts to degrade, if not outright lie about the evidence are even worse.) But what that scandal has done most tellingly is widen the space for scrutinizing other discomfiting aspects of America’s Game that are killing or, at least, muting the buzz of unconditional fandom.

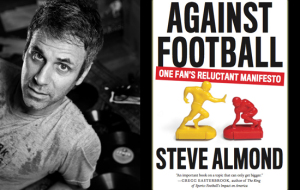

Against Football (Melville House) is written by Steve Almond, who describes himself as a long-time and, more recently, long-suffering Raiders fan. It’s probably a given that he writes this silken-swift j’accuse more from sorrow than anger; though he still sounds pretty mad at the NFL and, in equal measure, with “the two disparate synapses that fire in my brain that when I hear the word, “football”: the one that calls out, Who’s playing? What channel? and the one that murmurs, Shame on you.” This is from his introduction. He has me at “Hello.”

Almond goes on to debunk, among other things, the fallacy of the league’s “socialism” based on its revenue-sharing policy, which, through “a canny form of market manipulation” along with deft congressional lobbying allowed the NFL to circumvent anti-trust regulations. He also stretches open, to wince-inducing degrees, the homophobia, sexism and racism, conscious or otherwise, that fester beneath the sleek, supposedly more humane surface of 21st century play-for-pay tackle football. One chapter is entitled, “The Love Song of Richie Incognito,” which, given the story behind that name, sounds like a movie worth making, if not seeing. Another chapter title, “Their Sons Grow Suicidally Beautiful,” is taken from a James Wright poem about football (the best such poem from an American) and takes up the myriad ills of “amateur” football at all levels; not least of which the manner in which the collegiate game has become little more than a feeder system for the pro league in both manpower and added publicity, which, at this point, it can never get enough of. (I’m kidding.)

These and many other defects tabulated in Against Football aren’t exactly news to those old enough to have read the first-hand accounts of such renegade players of the sixties as Dave Meggysey, Bernie Parish and Peter Gent. But because Almond’s book is aimed as much as his own psyche as it is at ours, the passages that sting the most delve into the psychology of football fandom. He quotes, from Frederick Exley’s A Fan’s Notes, how the book’s autobiographical surrogate “gained…the feeling of being alive” from watching Giants games in dive bars. “His hero,” Almond writes of Exley, “looks to the Giants each Sunday to awaken him from the spiritual stupor of his life. That could be religion – or addiction.” (Italics added.)

I envision millions of people who hate the game but love a fan in their lives nodding their heads in rueful recognition of this phenomenon. And yet neither Almond nor I have easy answers as to whether being ambivalent about the game, but watching it anyway is a more destructive equivalent to substance abuse than loving the game while completely ignoring its moral and ethical lapses. That the question is posed at all raises this book above the level of a mere screed.

As trenchant as Almond is, he remains solicitous and compassionate throughout towards those whose devotion to football remains absolute. At one point, he quotes a close friend who, upon hearing of the book Almond intends to write, implores, “Please don’t take this away from me.” Towards the end, he’s utterly abased by a conversation he has with a young woman, a lifelong Philadelphia Eagles fan who tells him that football “was what kept her connected to her hometown, and to her dad especially.” Guess how low he felt when he answered her query as to what his book was about.

The Eagles. They do seem to inspire a river-deep-mountain-high devotion in their fan base. I spent eight years living and working in Philadelphia and though I was never converted to the Eagles cause (I do think you need to have grown up there to truly belong), I appreciated the city’s collective investment of passion somewhat more than those who from a distance view Eagles fans with varying degrees of alarm. Having interviewed those fans in full fury (and illumination) against their team, I can say that while they can be…how to put this…vivid in their expressiveness, I felt very safe in their company – as long as I never told them that I’d grown up in a Giants household. Such intense devotion along with a substantial historic legacy in professional football deserves more than one measly championship in the last 55 years to show for it.

Ray Didinger grew up an Eagles fan and spent most of his professional life writing about them for at least two local newspapers. He walks the walk, talks the talk of the true fan, but he’s so much more composed and rational about his engagement, which makes the second edition of The New Eagles Encyclopedia (Temple University Press), revised by Didinger from the 2005 edition he’d composed with the late Robert S, Lyons, both an invaluable tonic for the stressed-out Eagles follower and an absorbing read for anyone who savors colorful history and folklore, no matter where it’s from or what it’s about.

To pluck one example from many: Didinger’s chapter, new for this edition, about the team’s rivalry with the Dallas Cowboys. OK, OK…like, almost everybody has a rivalry with the Dallas Cowboys; at times, the Cowboys even hate themselves. But with the Eagles, it’s as if there are festering internal injuries that haven’t healed with time. And Didinger, who’s got the memory of an intelligence agency’s deep-background file system, reaches back to the mid-1960s when the two teams traded a series of wins and losses that climaxed with a jaw-breaking, teeth-severing clothesline tackle on Philadelphia running back Timmy Brown by Dallas linebacker Lee Roy Jordan. Eagle partisans maintain to this day that Jordan’s hit was late and cheap. Jordan insists otherwise. What Didinger characterizes as a “blood feud” was established from then on.

Brown, for what it’s worth, retained sufficient enough use of his oral equipment to have to a respectable career as a screen actor. (He’s in Nashville! Singing!) But in the context of this species of football book, physical injury is just the spoke on a wheel whose hub is the process of professional athletics itself. And even at a time when thoughtful people are coming to grips with their long-term affection for a brutal sport, Didinger’s book reminds you that devotion to a team and the people who live and die with its every game isn’t the only thing to think about when thinking about football. But for many people, it’s everything…and, much as some of us may disagree, enough.

September 7th, 2014 — on writing lit -- and unlit

Baseball books don’t need my help, or anybody else’s. There’ll always be waves of rhapsodists and elegists waxing year after year about the aesthetic virtues and time-tested verities of what used to be The National Pastime. Football books are another matter. For whatever reason, the literary/intellectual muse can’t get as revved up by what is now certified, for better and worse, as America’s Game.

A example, slight, perhaps, but mine own: In the 1992 Norton Book of Sports, edited by that would-be quarterback George Plimpton, there are roughly 70 stories, poems, essays and book excerpts covering baseball, boxing, basketball, horse racing and even skiing. Football, by my count, gets just three items. (Just saying…)

People give lip service to the idea of “beauty” emerging from the jolting, amoebic flow of a block-and-tackle football game. But most of the books published about that sport seem to have more to do with business than with beauty. The sport itself is often used as a metaphor for corporate culture with CEOs imagining themselves as the true legatees of Vince Lombardi and Bill Walsh, the heart and brain, respectively, of football coaching Valhalla. The push-pull collisions get taken as analogies for the rest of us working stiffs sticking our heads into the morass for the risk of reward and, as has become distressingly clearer in recent years, the reward of risk.

Rarely do I encounter a printed account of a breakaway run or a two-minute drill as lyrical as, say, John Updike’s oft-anthologized valedictory to Ted Williams’ final at-bat. But there may be built-in limits as to how best such moments can be persuasively rendered on a page. Baseball prose is allowed to bend and pitch to Mozart-ian levels; Prose about boxing, since we like stretching analogies till they scream in pain, can, at peak performance, surge ahead like a big-band swing orchestra blasting away in 4/4 time on a printed page.

The best, most evocative writing found in Football: Great Writing About the National Sport (The Library of America) comes across like vintage rock-and-roll with varied applications of blues, country and even a little gospel. Because I happen to know that the anthology’s editor John Schulian is a knowledgeable patron of blues and country music, I suspect he did as much reading with his ears as with his eyes when choosing selections. Even the elegies (Frank Deford’s homeboy-from-Ballmer memoriam to Johnny Unitas; Wright Thompson’s “Love Letter” to Ole Miss football; John Ed Bradley’s impassioned reverie about walking away from playing days at LSU) emit streaks of syncopated roughhousing. (“Unitas” Deford writes, “was some hardscrabble Lithuanian, so what he did made a difference, because even if we [Baltimoreans] had never met a Lithuanian before, we knew that he was as smart a sonuvabitch [sic] as he was tough. Dammit, he was our Lithuanian.”)

Schulian’s jukebox carries lively, varied selections that dare you to mix them around at will. You can punch up vivid reminiscences of pro football’s primordial days from gypsy leatherhead Johnny Blood (as rendered by the late Steelers broadcaster Myron Cope) or watch as Richard Price struggles to shake free of goddam-Yankee self-consciousness before entering the lair of Alabama demigod Bear Bryant. Coaches, generally, are the strangest of all the characters in this anthology, whether it’s George Allen, blustering and fidgeting his way through New Year’s Day 1968 after being ash-canned by the Rams (His daughter Jennifer is affectionate without being indulgent towards her dad’s fulminations) or Tom Landry, an oracular icebox of contradictions and piety who both bemuses and exasperates Gary Cartwright.

The editor’s own portrait of the greatest of Philadelphia Eagles, Chuck Bednarik is so richly textured that you stop regretting that he didn’t include the all-but-definitive description of Bednarik’s shattering 1960 tackle of Frank Gifford found in Frederick Exley’s A Fan’s Notes, a segment of which otherwise shares space in this collection with chapters from Paper Lion, the aforementioned account of George Plimpton’s adventures in training for exhibition football; Instant Replay, Green Bay offensive guard Jerry Kramer’s journal of the Packers’ last championship season under Vince Lombardi and Friday Night Lights, Buzz Bissinger’s by-now-canonical examination of playing out the fall season at a Texas high school.

Of the articles from magazines and newspapers selected by Schulian, I’m especially partial to the flamboyant deadline artistry Dan Jenkins deploys in his wry dissection of the hype-deflating Greatest-Tie-Ever-Played between Notre Dame and Michigan State in 1966 and to the consummate reportorial chops Arthur Kretchmer shows in his 1971 account of an up-and-down season in the career of the Chicago Bears fabled middle linebacker Dick Butkus. All the game’s elements — the harsh drudgery of practice, the moments of grace emerging from the sloughs of serial bashings, the grim spoils of brutality and their stoic acceptance by players – are contained and elucidated in Kretchmer’s masterly profile, whose closest counterpart in baseball is Al Stump’s landmark account of Ty Cobb’s final desperate days (even though Kretchmer’s subject is far less psychotic, if almost as mean.)

One feels like an ingrate to submit a qualm or two. Still, I wish Schulian hadn’t locked out entries more fictional than Exley’s novelized memoir. It would have been intriguing to see how the climactic football game from Richard Hooker’s M*A*S*H* would have stood with this crowd along with that venerable warhorse from Irwin Shaw, “The Eighty Yard Run” and some metaphysical hors-d’oeuvres from Don DeLillo’s End Zone.

Also, speaking from a racially chauvinistic perspective, I would have liked some representation in this book from such influential African-American sportswriters as Michael Wilbon or the late Ralph Wiley, whose gaudily Kafka-esque examination of O.J. Simpson’s guilt or innocence (though it likely doesn’t belong here anyway) remains for me the most thorough and persuasive dissection of that sordid episode in American celebrity jurisprudence.

But as George Blanda might have said if he were doing a commercial for Football: Great Writing About the National Sport, I can’t kick about a collection whose rapture over the written word and romance with a endangered species of sports journalism don’t prevent it from acknowledging, as Schulian writes in his introduction, the “storm clouds hanging over both the NFL and the NCAA” that are “bigger than any before them.” The collegiate clouds, mostly having to do with both abuses of NCAA rules and the association’s often myopic efforts at enforcing them, don’t get taken up in the anthology. But the NFL’s clouds are resolutely explored in such pieces as Mark Kram’s 1991 study of veteran players’ physical deterioration and Paul Solotaroff’s 2011 coroner’s report on Dave Duerson’s melancholy post-career slide into psychological despair in which the one endeavor the ex-Chicago safety was certain would have lasting value was taking his own life – and making sure his damaged brain was left intact for scientists to continue their inquiry into long-term effects of concussions.

The more one is made aware of cases like Duerson’s, the more one wonders if there’s any point in looking at football at all, much less remaining a steadfast fan. In addition to Football, there are new books that embody both these variables and I’ll tell you about them in the next installment.

August 7th, 2014 — jazz reviews

Back in the winter of 1993, I threw a newsroom tantrum over an article that appeared in Spy magazine under the title, “Admit It. Jazz Sucks.” Written by Joe Queenan, then riding the ascending curve as a go-to contrarian crank for major media outlets, the piece was a mordant rant against what he perceived as a stuffed-shirt conspiracy to shove jazz music down the zeitgeist’s collective throat.

Most readers, even those unsympathetic to Queenan’s sentiments (and no, he wasn’t kidding about those), found it relatively easy back then to take the whole thing as bilious faux-regular-guy philistinism and move on with their lives. But I’d come across this screed at a time when I was still struggling to convince my New York Newsday editors that jazz music deserved a broader, bigger regular presence in its pages. The last thing I needed to hear from a national magazine, ANY national magazine, was a brash, loud voice suggesting to the editors that, well, yeah, maybe we don’t need to deal with this intimidating, complicated, provocative music that isn’t even as popular as it used to be. In other words, I took the damn thing personally – and stomped my feet, bellowed out loud, pounded furniture, etc. to let everybody I worked for, and with, know of my purple-cheeked displeasure.

And another thing: How exactly did Queenan figure that jazz was this domineering entity imposing itself upon whatever culture he believed himself to represent? If anything, jazz was catching more hell from the mainstream than it was receiving. Why the hell didn’t Spy magazine pick on somebody/something its own size? On top of everything else, it wasn’t even funny. Or smart. Even one of my editors, a rock-and-roller who like to bait me with similar anti-jazz bombs, thought the piece was lame –and, therefore, not worth getting ulcers over.

Indeed, after I’d calmed down and realized that I was all alone not just in detesting, but even caring much about the piece, it occurred to me that the very lack of furor generated by the article was dismal proof that even if Queenan was right about this conspiracy, it was already failing.

So life did in fact go on: Spy eventually folded. Queenan wrote better, if more bilious pieces. Newsday ended its noble New York City-based experiment. And jazz still came out at the other end of the century barely breaking even in the music marketplace. So all I can say to all my friends and fellow-travelers in the jazz universe who’ve been seething since last week over what I’ve come to know as the “Unfunny Sonny” blog on The New Yorker’s web site is this: I been there already.

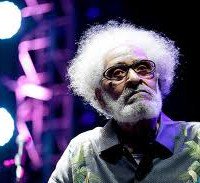

Briefly, for the rest of you: About a week ago (though it seems longer), a piece began circulating on the web under the New Yorker’s aegis under the title, “Sonny Rollins: In His Own Words.” Only it sure didn’t sound like Sonny Rollins; more like a whiny savant who likened the sound of a saxophone to a “scared pig” and doesn’t see the point of jazz and hates his whole life. “If I could do it all over again, I’d probably be a process server or an accountant. They make good money.” You get the idea. If you don’t, here’s the rest of it.

It now sounds weird, but more than a few people who first came across this thing on social media sites actually thought that this was Rollins’ voice. (I recall one musician first reacted by thinking that this outburst was the result of Rollins playing for too long with substandard backup musicians. Which was almost as funny – or not – as the piece itself.) As the civilized world now knows, a senior writer for The Onion named Django Gold wrote it and, as you’ll now notice, the blog now comes with disclaimers. Why? Partly because of this loud, resounding, universal outcry from the jazz musicians, fans and journalists that, collectively, made my office tantrum of twenty-one whole years ago seem like a sneeze in a noisy stadium. (By the way, after reading Gold’s piece again, make sure you watch this afterwards if only to make clearer whose voice is who’s.)

I suppose I, too, was more annoyed than amused by Gold’s little joke at jazz’s expense and the reasons are pretty much in line with those enumerated over the last few days. To wit:

1.) You mean The New Yorker no longer has the time or space to cover jazz on a regular basis and THIS is what they decide to contribute instead?

2.) Jazz is still fighting to hold on to its sliver of the music marketplace and here’s one of the leading publications in the country demeaning its greatest living improviser? How dare they! Would they do this to Tom Stoppard or Suzanne Farrell or anybody in opera?

3.) It’s not all that funny to begin with. Why waste the space, especially at jazz’s expense? I’m probably leaving out a few other complaints, but these three are among the more frequent, making it easier to take them each of them one at a time:

1.) That the New Yorker hasn’t bothered finding room for regular jazz coverage, especially after establishing a tradition for such through the late Whitney Balliett is, of course, an ongoing scandal. But no one else in the magazine world is bothering with it either. I can understand concerns among my fellow jazz lovers that the snide tone informing this parody will convince the music’s haters of their fine judgment and good taste. I don’t know. Outright jazz hate is annoying, but widespread indifference is worse. Does anyone besides me remember Stanley Crouch’s 2005 straight-ahead New Yorker profile of Rollins? Do I remember any profile of any jazz musician since then of similar heft and dimension? I do not. And whenever a newspaper or mainstream publication paid me to write about jazz, I often felt as if I were dropping pebbles down a deep, dark well waiting for the splash. I’d like to think the furor aroused by Gold’s prank would shame editors into changing this situation. I know better. They’d prefer more pranks. So does the Internet. So do the people who get caught up in the Internet. I play the sincerity card with jazz because I respect it too much to do otherwise. But when I praise Sonny Rollins, I’m basically telling people what they already know, whether they’ve heard him for themselves or not. Snide plays better than sincere. Or don’t you listen to “Wait, Wait, Don’t Tell Me” every week on NPR? Figured as much.

2.) Nevertheless, I, too, would rather read or write about the latest installment of Rollins’ “Road Shows” albums than see somebody reduce Sonny to the rough equivalent of a petulant preppie. I’ve often said that while critics sometimes pump up everything Rollins does with little discrimination, the public-at-large seriously underrates or altogether ignores his glorious inventiveness. (Those who wonder why everybody in jazz got so riled by Gold’s piece should immediately buy Road Shows, Vol. 3 or, to get it all over with, Saxophone Colossus.) On the other hand, Gold or his editors must already think that Rollins has the kind of heft and dimension as a figure to be poked at and hazed in the public square, which is kinda sorta a backhanded acknowledgment of his significance. Would somebody do the same to Tom Stoppard or Suzanne Farrell or anybody in opera? You bet your sweet ass somebody would, anybody would, early and often! To say that jazz can’t take even the most half-baked pies tossed at its kisser is to make it seem as reductive as snobs in the higher elevations of Culture Gulch believe it to be.

3.) Then, too, opera buffs and balletomanes in those higher elevations are often regarded as humorless wet blankets who can’t abide the cheap jokes as their expense. The jazz cognoscenti may even acknowledge the irony that its collective cri-de-coeur over Gold’s blog only confirms the outer world’s suspicions that we’re all a bunch of insular, thin-skinned spoilsports who can’t take a joke. But that the joke in question needed a disclaimer to chill out the complainers may prove that the joke in question wasn’t all that funny to begin with. For what it’s worth, it’s a helluva lot funnier than Queenan’s smug tirade, though, unlike Queenan, Gold doesn’t seem at all sure of what he’s skewering in the first place — and neither does the reader. It’s a piece interested more in striking a pose than making a point. It assumes an attitude about something that isn’t the least bit connected or concerned with what its satirizing; unlike Donald Barthelme’s New Yorker story, “The King of Jazz,” which was the kind of blithe-but-pointed mockery that only a true fan (which Barthelme was) could pull off. Nevertheless, given the new-school dynamics of media transactions, strike a pose conspicuously enough and most of the gawkers will believe you’ve made your point anyway. And while jazz fans are shamed by Gold, he’s not shamed at all. He’s hearing tinkling sounds – bells, coins — whenever somebody mentions his name. If taking Gold to task for demeaning jazz makes me look like a slow-burning Edgar Kennedy to his blithe Harpo Marx, I’d just as soon go back to bed and wait for the wind to die down.

All this said, I’m glad, and even proud, that jazz got on its hind legs and roared back at this squib. The furor wont raise the music’s profile any higher than it is now. Too many other things have to happen for that to change. But as with that Spy magazine assault long ago, the effects of which I think I’m finally over by now, jazz under whatever name in whatever state will go on, oblivious to whatever the lovers and haters say about it. As I said earlier: I been here before. So will the divine mysteries of music. And so, I trust, will writers who can riff, lick and even vogue better than…no, sorry. I’m not going to mention the name again. I’d rather give my remaining time to this guy –– and, just as I eventually did twenty years ago, move on.

August 6th, 2014 — movie reviews, TV reviews

So I watched The Maltese Falcon yesterday afternoon, partly in celebration of John Huston’s birthday, partly because I hadn’t seen it in a while. Its stock has risen and fallen with me over the decades, though never TOO low (or as low as it often fell with hard-core auteurists). Now I’m all grown-up and unequivocally accept it as a classic. But this time around, as I was watching Humphrey Bogart making his way from his office to his apartment and back again, I wasn’t thinking about him so much as I was thinking of Philip Seymour Hoffman’s star turn in A Most Wanted Man. And I realized, finally, why so many people who saw that movie are feeling even more desolated by Hoffman’s passing earlier this year.

Some perspective: Before Falcon, Bogart had been known primarily as a character actor specializing in bad-guy roles; most of them variations of Duke Mantee, the sneering fugitive killer from The Petrified Forest that established his name on stage and screen. As Sam Spade, Bogart carried some of the sinister aura he’d patented in his previous movies and was able to channel it into what Pauline Kael aptly described as an “ambiguous mixture of avarice and honor, sexuality and fear.” It was Bogart’s first “good-guy” role, though given Spade’s icy duplicity and casual cruelty one could more properly characterize it as anti-heroic, or “bad-good guy”. Nevertheless, the movie’s success made Warner Brothers and, by extension, the public regard this brooding, battered-looking fellow as someone who could be a romantic figure; a conflicted one at times, perhaps, but an enviably tough one for sure.

Philip Seymour Hoffman’s situation before Most Wanted Man was quite different from Bogart’s before Maltese Falcon. By the time he’d died of a heroin overdose this past February, Hoffman was regarded as one of our finest actors, perhaps, the greatest of his generation. His versatility won him acclaim, awards and a kind of stardom that hadn’t yet translated to heroic or romantic leads; mostly, he was cast as eccentric, sweet, awkward or malevolent characters. If Kael’s description of Bogart’s Spade could have been applied to any of Hoffman’s roles, it likely would have been Lancaster Dodd, the mercurial cult leader and title character of 2012’s The Master. It’s probable that after playing a such a magnetic composite of eccentricity, sweetness, awkwardness and malevolence Hoffman may have started wondering where else he could carry this trick bag and to what end.

So he began trying on some different wardrobe; first as a working-class mensch in God’s Pocket and as Most Wanted Man’s Gunther Bachmann, the rumpled German intelligence operative struggling to finesse the capture of a Muslim statesman suspected of funneling money to terrorists. Gunther is very much in the tradition of John Le Carre’s seedy spymasters; as with George Smiley, Gunther’s idea of getting results is to dig deep, stalk the edges, probe for soft spots and extract information as deftly as possible with no whistles and horns in sight. The strain of maintaining Gunther’s professional integrity shows in the way he wearily saunters into cafes and meeting rooms. Those working with or against Gunther’s tactics seem to have the edge because of their greater physical definition. Yet Gunther’s wooliness is deceptive, calculatedly so. Hoffman carries his character’s authority with a bruised, but stolid Old World dignity. You understand why his team will follow him everywhere and anywhere he takes them – and why his reluctant recruits end up trusting him despite their most urgent reservations.

As for the romantic part, there’s a moment, only a moment, where the possibilities make themselves apparent. It comes when Gunther, in an attempt to conceal his presence from somebody on an illuminated nighttime street, grabs his subordinate Irma (Nina Hoss) and embraces her in a faux-make-out clinch. When they break off, Irma’s hand lingers gently on Gunther’s back. The moment passes, but it’s one of the few times in director Anton Corbijn’s thriller where you’re aware of something going on just beyond the narrative’s whirring machinery.

You’re also aware of something happening with Hoffman’s screen image beyond his already-legendary chameleon chops. You think of the possibilities opened up by having someone as unkempt as a fraternity hall closet after a beer party somehow embody an heroic archetype that movie audiences throughout the world could embrace as cozily as Irma does Gunther. I’m not saying Hoffman’s performance in Most Wanted Man would have allowed him to pursue his own Casablanca or To Have and Have Not. But, putting it as painlessly as possible, it would have been great fun to see him go for it.

The recent death of James Shigeta at 85 evokes a different, but no less poignant sense of lost or forsaken possibilities. Shigeta, as many knowing and respectful tributes have mentioned, had a long and influential career as both dramatic actor and musical-comedy performer. Blessed with a deep, melodious speaking voice, Shigeta broke down racial barriers from the start of his career, playing a police detective in Samuel Fuller’s iconoclastic 1959 thriller, The Crimson Kimino, in which his character becomes romantically involved with Victoria Hall’s imperiled Caucasian witness.

It wouldn’t be the only time he’d played someone in an interracial romance or for that matter, someone in a romantic lead. And it seemed for a while as though his magnetism and grace would pay off in major stardom despite the compartments Hollywood still tended to place roles for Asian actors.

But Shigeta, though always in demand in movies and television, never became a major star; not even during a twenty-year span – the sixties and seventies – when the nature of what it meant to be a movie star was expanding enough to encompass the previously non-traditional likes of Sidney Poitier, Barbra Streisand and Dustin Hoffman. Maybe the movies couldn’t do it, but television was, and is, a different proposition, more open to tweaking expectations in the name of getting attention – and ratings.

Knowing Shigeta was originally from Hawaii made me imagine a bit of alternative history that, had it actually come to pass, might have helped make a different world. It certainly would have made for an obituary different from the ones widely circulated late last month.

So let’s all imagine, shall we?

LOS ANGELES, July 29, 2014 – James Shigeta, the groundbreaking Asian-American leading man, who achieved his greatest success as star of the long-running CBS police series, “Hawaii Five-O”, died Monday of pulmonary failure. He was 85.

Shigeta, born in what was then the Hawaii territory of the United States to Asian American parents, achieved early success as both a movie actor and as a singer who performed in the 1960 film adaptation of “Flower Drum Song,” the Rodgers-and-Hammerstein musical comedy about arranged marriages among Chinese-Americans.

But it was the role of Detective Lt. Rick Nakamura on “Hawaii Five-O” that made Shigeta a household name in America and throughout the world. In the process, it accelerated the broadening presence of non-white actors on the big and small screens in roles that traditionally went to whites.

“I will always be grateful to Rick Nakamura and everything he gave to me,” Shigeta said in later years. “Once you’ve done TV for as long as I have, you’re never a stranger, no matter where you go in the world.”

It very nearly didn’t happen, according to the late Leonard Freeman, who created and produced “Hawaii Five-O.” Back in 1967, when the idea for a series about an elite crime-fighting unit based in Honolulu reached the development stage, Freeman recalls that while casting Asian actors as cast regulars was never in doubt, the notion of the team’s leader being Asian met with resistance from CBS executives.

“They were adamant,” Freeman recalled in 1971 when the series was in its third season. “But I kept at it, telling them that, after all, we were in a time when Bill Cosby was winning Emmys as a lead character on ‘I Spy.’ But the network was certain that people weren’t ready for an Asian cop leading a series. I kept telling them that just the curiosity of the idea, along with all that beautiful scenery, would give them everything they wanted.”

Shigeta, who jumped at the chance for steady work in the land of his birth, made his own pitch to CBS executives. Apparently that was all it took – and the rest was television history, though, as Shigeta recalled later, it took a while for the show and his stardom to take hold.

“An Asian leading man on prime-time television wasn’t exactly business as usual in 1968,” he told a Time magazine interviewer in 1975. “In fact, there were so many people [at CBS] who were so sure it wouldn’t take that they were already talking about midseason replacements the same m0nth we went on the air. I got so depressed by the low expectations that by season’s end, I’d prepare for the hammer to fall and I’d start trying to figure out what to do with my life afterwards.

“Then we got renewed. But we carried those same low expectations into season two, even with all the awards we were getting. And I’d get that same sinking feeling.. Seven years later, we’re still around, so I guess everybody’s stopped worrying.”

Eventually, “Hawaii Five-O” ran twelve seasons, from 1968 to 1980. Shigeta’s good looks, silkily resonant voice and ramrod presence allowed Rick Nakamura to become as familiar to TV viewers as James Arness’ Matt Dillon from CBS’ comparably durable “Gunsmoke.” Backed by a supporting cast that included James MacArthur, Kam Fong and Gilbert Lani Kahui , whose professional name was Zulu, Shigeta’s Nakamura conveyed a deceptively impassive demeanor magnetic enough to establish what TV critic Ken Tucker would later characterize as a “paradigm of absolute cool” that actors of all nationalities would try duplicating with mixed results.

What helped seal Nakamura’s immortality was the way Shigeta would reliably intone, at or near the end of each episode, “Book ‘em, Dann-O!” to MacArthur’s Danny Williams with icy resolve.

Shigeta was nominated for Emmys six times, winning for Best Lead Actor in a Dramatic Series in 1969, 1970 and 1973. Once the show achieved steady success, Shigeta used his growing influence to ensure that other non-white actors would be given roles that would not be denigrating . He especially made sure that all his co-stars received extensive screen time, even their own episodes. MacArthur won a Best Supporting Actor Emmy in 1971 and Kahui and Fong credit their exposure on “Hawaii Five-O” for securing roles in major motion pictures, including 1988’s “Die Hard” in which they played Asian businessmen who sacrifice their lives for hostages.

MacArthur, in accepting his Emmy, credited Shigeta for the collegial atmosphere he helped sustain throughout the show’s run. “A great actor without a big ego. He’s a freak of nature!”

Shigeta parlayed his TV notoriety into a modestly successful career as a nightclub singer and recording artist. He was always puckishly proud that his 1971 version of Rod McKuen’s “Cycles” beat out Frank Sinatra’s 1968 version by reaching number 15 on the Billboard pop charts. “Something else,” he noted wryly in the Time interview, “to thank Rick Nakamura for.” (For his part, Sinatra held no grudges against Shigeta’s coup, saying, “That’s what happens when you’ve been out-acted by a fine actor.”)

By 1974, Shigeta had acquired enough clout with both the show’s producers and the network to get them to agree to casting his “Flower Drum Song” co-star Nancy Kwan as a series semi-regular. Her role as enigmatic federal agent Joanna Ming was considered as much a groundbreaker in series television as Shigeta’s and in 1978 her character was “spun off” into her own CBS action series, “Undercover,” that lasted until 1981.

Shigeta recalled being exhausted by that last season of 1979-80 and took a six-year leave-of-absence from show business. Hawaii Democrats proposed that he run for governor in 1986. Though intrigued, Shigeta demurred, insisting that, however much he wanted to effect change for people-of-color, he could do the most good in his chosen profession. Instead, he agreed to ease back into the medium in a recurring role on “L.A. Law” as Judge Danforth Akiyoshi.

He admitted that it was “funny, at first” when actors on the series would insist on muttering, “Book ‘em, Dann-O” between takes. “I’d always tell them they didn’t quite have it right,” he said. “And they were always crestfallen when I did. Gosh, I didn’t think they’d take it so personally.””

July 23rd, 2014 — jazz reviews

As of this Friday, Charlie Haden will have been off the planet for two weeks. Yet I’m still tripping over him in unexpected places. Earlier this week, for instance, I put on an ECM compilation of Carla Bley’s work and all of a sudden, this voice pours out of the speakers that sounded a lot like Linda Ronstadt’s from her daisy-fresh Stone Poneys days. Turned out that’s exactly who it was: Ronstadt doing lead vocals on Bley’s “Why?” from the 1971 jazz opera, Escalator Over The Hill. And who should be vocally harmonizing with her on this track, in what sounds like the bluegrass idiom of his childhood professional days, but Haden, who also played double-bass for Bley’s orchestra.

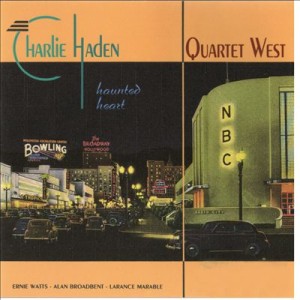

As of this Friday, Charlie Haden will have been off the planet for two weeks. Yet I’m still tripping over him in unexpected places. Earlier this week, for instance, I put on an ECM compilation of Carla Bley’s work and all of a sudden, this voice pours out of the speakers that sounded a lot like Linda Ronstadt’s from her daisy-fresh Stone Poneys days. Turned out that’s exactly who it was: Ronstadt doing lead vocals on Bley’s “Why?” from the 1971 jazz opera, Escalator Over The Hill. And who should be vocally harmonizing with her on this track, in what sounds like the bluegrass idiom of his childhood professional days, but Haden, who also played double-bass for Bley’s orchestra.  A day later, I finally caught hold of Last Dance, the recently-released ECM album with Haden and one of his old bosses, Keith Jarrett, performing classic pop standards. Though these duets were recorded in 2007, the album’s ruminative tone and sepulchral title, augmented by having “Every Time We Say Goodbye” and, then, “Goodbye” as back-to-back concluding numbers, seem to emit melancholy prophesy. Except I don’t feel in any way saddened while listening to these intimate conversations between two veterans who, though working with traditional chord progressions and stone-ground rhythms, find new ways to make these warhorses enrapture and inspire. Which may be another way of saying that nothing much has changed and Charlie Haden will somehow always be with us, letting his romanticist’s gospel of Beauty and Truth filter through the world where, through most of his 76 years, he spread this gospel broadly, but never thinly. We could be spending almost as many years wandering through and assessing his prolific contributions as sideman, leader, composer, collaborator and movie director. You read right. Movie director. And while you wont find his name listed as such on the Internet Movie Database, Charlie Haden excelled at making movies of the mind, even when he wasn’t trying. Born in 1937, Haden was a child of both motion pictures and the radio and, thus, instinctively understood how the former so robustly fed people’s imaginations, which were comparably stimulated by the latter. Just as the movies could make you want to get up and dance, orchestrated sounds could make you lie back and dream. By the 1950s, the movies would help dictate how we listen to music. (Think of all those set-the-mood-for-making-out LPs of the era with lush strings.) And Haden became one of the auteurs of concept albums that, openly or otherwise, borrowed their tropes from cinema. Most especially, what became known as the Hollywood noir movies of the forties and fifties became a recurring motif with Haden’s Quartet West albums on Verve, beginning with 1986’s eponymous album introducing the quartet – saxophonist Ernie Watts, pianist Alan Broadbent and drummer Billy Higgins, Haden’s onetime band mate with Ornette Coleman, replaced with Larance Marable on 1988’s In Angel City.

A day later, I finally caught hold of Last Dance, the recently-released ECM album with Haden and one of his old bosses, Keith Jarrett, performing classic pop standards. Though these duets were recorded in 2007, the album’s ruminative tone and sepulchral title, augmented by having “Every Time We Say Goodbye” and, then, “Goodbye” as back-to-back concluding numbers, seem to emit melancholy prophesy. Except I don’t feel in any way saddened while listening to these intimate conversations between two veterans who, though working with traditional chord progressions and stone-ground rhythms, find new ways to make these warhorses enrapture and inspire. Which may be another way of saying that nothing much has changed and Charlie Haden will somehow always be with us, letting his romanticist’s gospel of Beauty and Truth filter through the world where, through most of his 76 years, he spread this gospel broadly, but never thinly. We could be spending almost as many years wandering through and assessing his prolific contributions as sideman, leader, composer, collaborator and movie director. You read right. Movie director. And while you wont find his name listed as such on the Internet Movie Database, Charlie Haden excelled at making movies of the mind, even when he wasn’t trying. Born in 1937, Haden was a child of both motion pictures and the radio and, thus, instinctively understood how the former so robustly fed people’s imaginations, which were comparably stimulated by the latter. Just as the movies could make you want to get up and dance, orchestrated sounds could make you lie back and dream. By the 1950s, the movies would help dictate how we listen to music. (Think of all those set-the-mood-for-making-out LPs of the era with lush strings.) And Haden became one of the auteurs of concept albums that, openly or otherwise, borrowed their tropes from cinema. Most especially, what became known as the Hollywood noir movies of the forties and fifties became a recurring motif with Haden’s Quartet West albums on Verve, beginning with 1986’s eponymous album introducing the quartet – saxophonist Ernie Watts, pianist Alan Broadbent and drummer Billy Higgins, Haden’s onetime band mate with Ornette Coleman, replaced with Larance Marable on 1988’s In Angel City.  The other Quartet West Verves – 1990’s Haunted Heart, 1993’s Always Say Goodbye, 1995’s Now is the Hour and 1999’s The Art of the Song – were more or less pastiches of movie soundtracks, vintage recordings by such diverse artists as Jo Stafford, Jeri Southern, Chet Baker, Billie Holiday, Duke Ellington, Coleman Hawkins and Django Reinhardt. (In the last entry, a full orchestra and singers Shirley Horn and Bill Henderson joined the quartet in the studio.) Critics were mostly enchanted with these discs when they were first released, even though you could hear grousing from some corners that Haden was squandering his considerable energies on studio gimmickry; a kind of “sampling” for nostalgic grownups. But Haden had earned wellsprings of credibility that began to collect around his name in the late 1950s when he’d helped rearrange the furniture in listeners’ heads for all time as a member of Ornette Coleman’s epochal quartet. He’d also put his music where his progressive politics were as founder-leader of the Liberation Music Orchestra and burnished his reputation by helping enhance those of such diverse artists as Geri Allen, Kenny Barron, Hampton Hawes, Abbey Lincoln, Hank Jones, Paul Motian, Bley and Jarrett by sitting in or collaborating with them, live or on record. Whether you dug Haunted Heart or Always Say Goodbye depends on how much you happen to be into the same old movies that Haden was. And Haden’s affinity for Raymond Chandler and other SoCal literary lights was genuine enough to give added integrity and sturdiness to his dreamscapes. Unlike a lot of actual filmmakers, Haden didn’t see those crime melodramas as excuses for ironic reinvention or post-modern hijinks. He thought Chandler and his ilk were funny, incisive and, most of all, relevant enough for whatever present-day reality you inhabit. His perpetual sense of wonder with the sunset-infused landscape of modern jazz and tarnished dreams was infectious – and you were motivated as he seemed to be to imagine your own movies sequences to match the music.

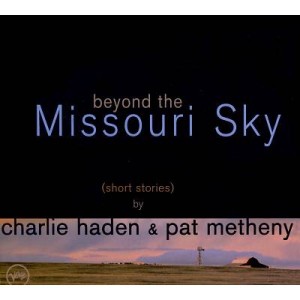

The other Quartet West Verves – 1990’s Haunted Heart, 1993’s Always Say Goodbye, 1995’s Now is the Hour and 1999’s The Art of the Song – were more or less pastiches of movie soundtracks, vintage recordings by such diverse artists as Jo Stafford, Jeri Southern, Chet Baker, Billie Holiday, Duke Ellington, Coleman Hawkins and Django Reinhardt. (In the last entry, a full orchestra and singers Shirley Horn and Bill Henderson joined the quartet in the studio.) Critics were mostly enchanted with these discs when they were first released, even though you could hear grousing from some corners that Haden was squandering his considerable energies on studio gimmickry; a kind of “sampling” for nostalgic grownups. But Haden had earned wellsprings of credibility that began to collect around his name in the late 1950s when he’d helped rearrange the furniture in listeners’ heads for all time as a member of Ornette Coleman’s epochal quartet. He’d also put his music where his progressive politics were as founder-leader of the Liberation Music Orchestra and burnished his reputation by helping enhance those of such diverse artists as Geri Allen, Kenny Barron, Hampton Hawes, Abbey Lincoln, Hank Jones, Paul Motian, Bley and Jarrett by sitting in or collaborating with them, live or on record. Whether you dug Haunted Heart or Always Say Goodbye depends on how much you happen to be into the same old movies that Haden was. And Haden’s affinity for Raymond Chandler and other SoCal literary lights was genuine enough to give added integrity and sturdiness to his dreamscapes. Unlike a lot of actual filmmakers, Haden didn’t see those crime melodramas as excuses for ironic reinvention or post-modern hijinks. He thought Chandler and his ilk were funny, incisive and, most of all, relevant enough for whatever present-day reality you inhabit. His perpetual sense of wonder with the sunset-infused landscape of modern jazz and tarnished dreams was infectious – and you were motivated as he seemed to be to imagine your own movies sequences to match the music.  As fond as I am of the Quartet West discs, I’ve come to believe since his passing that Haden’s greatest achievement as a moviemaker-for-the-mind lies somewhere beyond its body of work. It took me a long time even to appreciate Beyond the Missouri Sky, Haden’s 1996 session with guitarist Pat Metheny as anything more than a decorative collection of spare, wide-open-spacey duets. I am now one with the eighth edition of The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings, which places Missouri Sky among its “Core Collection” rankings. Even as a studio artifact, this album handsomely rewards re-listening with its overdubs and harmonic tracks. Haden’s melodic tone on the bass achieves depth and richness that coax greater fluidity and fineness from Metheny’s playing. The landscapes they evoke have big skies and gilded shadows. The mind movies here are less rooted in genre and more reminiscent of Rohmer or Antonioni in an avuncular mood. The latter didn’t make Cinema Paradiso, but there are nonetheless two pieces from that movie’s soundtrack along with Henry Mancini’s poignant theme from Two for the Road. And it gets even more personal than usual here: Roy Acuff’s “The Precious Jewel,” the mountain folk song, “He’s Gone Away” and Haden’s haunting original hymn, “Spiritual” are clearly intended to be tributes to the bassist’s parents, with whom he’d performed bluegrass and country ballads on radio when he was a little boy. Beyond the Missouri Sky was the first thing I thought of playing when I’d heard he’d died – and the sun was actually setting by the time “Spiritual” had run its course. It was less a funereal experience than a healing one. And I suspect it wont be the last time it will help ease the sting of bad news. After all, the movies he made weren’t distractions. Charlie Haden intended for his music – all of it — to be of use. What else are Truth and Beauty for?

As fond as I am of the Quartet West discs, I’ve come to believe since his passing that Haden’s greatest achievement as a moviemaker-for-the-mind lies somewhere beyond its body of work. It took me a long time even to appreciate Beyond the Missouri Sky, Haden’s 1996 session with guitarist Pat Metheny as anything more than a decorative collection of spare, wide-open-spacey duets. I am now one with the eighth edition of The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings, which places Missouri Sky among its “Core Collection” rankings. Even as a studio artifact, this album handsomely rewards re-listening with its overdubs and harmonic tracks. Haden’s melodic tone on the bass achieves depth and richness that coax greater fluidity and fineness from Metheny’s playing. The landscapes they evoke have big skies and gilded shadows. The mind movies here are less rooted in genre and more reminiscent of Rohmer or Antonioni in an avuncular mood. The latter didn’t make Cinema Paradiso, but there are nonetheless two pieces from that movie’s soundtrack along with Henry Mancini’s poignant theme from Two for the Road. And it gets even more personal than usual here: Roy Acuff’s “The Precious Jewel,” the mountain folk song, “He’s Gone Away” and Haden’s haunting original hymn, “Spiritual” are clearly intended to be tributes to the bassist’s parents, with whom he’d performed bluegrass and country ballads on radio when he was a little boy. Beyond the Missouri Sky was the first thing I thought of playing when I’d heard he’d died – and the sun was actually setting by the time “Spiritual” had run its course. It was less a funereal experience than a healing one. And I suspect it wont be the last time it will help ease the sting of bad news. After all, the movies he made weren’t distractions. Charlie Haden intended for his music – all of it — to be of use. What else are Truth and Beauty for?

May 16th, 2014 — movie reviews

Spider-Man, amazing or not, can wait. So can Godzilla and Seth Rogin. I can afford to let them all wait because I’ve been out of the weekly movie-reviewing routine since Obama’s first term and the best part about NOT being tethered to professional routine as a moviegoer is that you can go wander at will into something that’s already been thoroughly hyped or strafed without having to organize your own 400-500-word reaction as you’re watching it. Trolling and fishing away from the mainstream makes up one of the arcane, old school joys of cinephilia; one that’s completely lost in this marketplace of shiny new toys that often shatter or wither minutes after being unwrapped. I didn’t want bright and shiny and obvious. Those will wait. I wanted oily and murky and subtle. Which never do.

And darkness was where I most wanted to go this past week to catch up on what I missed…and to do so before some of these movies went away. DC is a good movie town, but as with all markets smaller than NY or LA, the theaters in Your Nation’s Capital tend not to let smaller, relatively under-the-radar stuff linger too long in their rotation. So this was, mostly for the better, how my week went:

Blue Ruin – Did I recognize Eve Plumb towards the end of writer-director Jeremy Saulnier’s spin-dry variations on the vigilante-movie formula? I did not, remembering her mostly as a little person on “The Brady Bunch,” whose early 1970s heyday was somewhat past my use-by date for family-friendly sitcoms. Seeing the artist-formerly-known-as-Jan-Brady’s name scroll by in the cast credits, however, was enough to trigger my one misgiving about this otherwise foxy thriller about revenge-obsessed Dwight (Macon Davis), whose parents’ murder years before apparently led to his becoming a wan, accident-prone dumpster diver haunting Delaware shore parking lots and bathing in vacant summer homes. When the man jailed for his parents’ murder is released, Dwight hunts for and eventually stabs the ex-con to a gruesome death in a public rest room. So begins a rat’s nest of mutual retribution as the man’s family comes after Dwight and his sister (Amy Hargreaves), a single mother of two, who’s way too level headed to hang around this story for very long. “I’d forgive you if you were crazy,” she tells Dwight before taking her little ones off to Pittsburgh for safety’s sake. “But you’re not. You’re weak.” So much for the broad-shouldered verities of Walking Tall and Kicking Ass, which Sauliner’s script deflates with such delicacy that Dwight’s seemingly inexhaustible luck and pluck look more pathetic than heroic. Still, Davis’s doe-eyed intensity and well-oiled anxiety keep you from writing Dwight off as emphatically as his sister does.

Blue Ruin’s espresso-edgy inversion of the revenge fantasy genre along with the movie’s backwoods strip-mall ambiance has aroused comparisons to Blood Simple. That alignment’s somewhat off, I think; for one thing, Ruin somehow manages to be both leaner in execution and richer in design than the Coen Bros. 1984 neo-noir. But I also wished there were maybe a little more wit in Saulnier’s script beyond the throwaway admission from one of Dwight’s nemeses (Kevin Kolack): “Yeah, well, killin’ the mother wasn’t the brightest move on our part, I’ll give ya that.”

And while the inevitable chaos at the end buttresses the movie’s point about revenge’s pointlessness, seeing Plumb as the matriarch of Dwight’s equally vindictive (and unhinged) antagonists made me wonder whether Saulnier’s point would have been sharpened by making that family as smooth-faced and as all-American polished as…the Brady Bunch. Maybe you risk unsettling and confusing audiences by making such moves, but isn’t that what’s supposed to happen along the cutting edge? That aside, I’d still take Blue Ruin over the next serial-killer melodrama a big studio tries to put over on us.

Under the Skin – Maybe Jonathan Glazer should consider switching the title of his 2000 crime thriller, Sexy Beast with this one. The title’s unavoidable when you see Scarlett Johansson’s laconic, dark-haired predator cruising the streets of Edinburgh at all hours asking male strangers for directions or slowly stripping off her clothes as some of the poor saps who decide to ride home with her sink naked behind her into an inky pool of oblivion. Who or what Johansson’s character is and what she and her peripheral motorbike-racing enablers do with the bodies of her captives are subject to interpretation, though what little you’re permitted to see will likely make you wish you hadn’t.

In a way, Johansson’s austere, elementally restrained performance (the kind that never ever gets recognized at awards time) is a companion piece to her invisible, all-vocal and just as sensitively-realized performance in Her, another SF movie that annoyed almost as many people as it engaged Some reviewers, for instance. have complained of an overabundance of implication in Glazer’s SF-horror chamber piece. Their grousing is another reason to be depressed since, once upon a time, even mainstream audiences would have been more than OK with leaving blank spaces open for interpretation. (And not just in foreign product – or doesn’t anybody besides me like to stay up on weekends to watch Val Lewton movies like The Seventh Victim?)

Anyway, what matters in Under the Skin is what happens to Johansson’s alien invader and not to her victims, one of whom is a shy, physically deformed recluse who is almost as icily reserved as she is. Somehow, this encounter sets off a nascent curiosity within her about the nature of this earthly form she inhabits, whether checking out the voluptuous contours of her naked body or chucking up a slab of chocolate cake she tries, and fails, to consume. She’s trying to figure out what being human means. In the process, we’re trying to figure that out along with her. Some people say that theme – which is the basic raison d’etre of any science fiction worth your time – is neither original nor interesting. This beef against SF isn’t original either. But Under the Skin is, especially when framed against more hi-tech, in-your-face techno-fantasies. I wish there were more movies like it, the more obscure, the better.

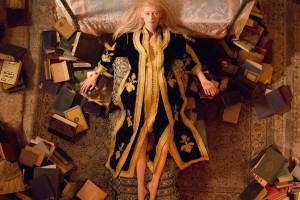

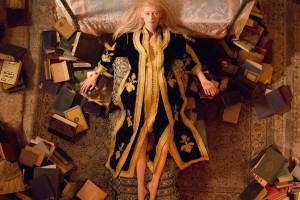

Only Lovers Left Alive –Jim Jarmusch isn’t the first art-house icon whose work acquires greater definition when it tethers itself to genre – and with any luck, he won’t be the last. While I find something to like about all his movies, even when, as in 1989’s Mystery Train or 2009’s The Limits of Control, he rambles and wanders his way around, or past, resolution, I think he is at his most arresting when his insouciant, deadpan imagination is taken up with the western (1995’s Dead Man), the crime thriller (1999’s Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai) and even the escape-from-prison subgenre (1986’s Down by Law).

He’s finally taken up with vampires and you wonder what took him so long, especially when Only Lovers Left Alive turns out to be, all at once, his wittiest, zestiest and most touching film ever. This is the vampire movie as a hipster hang – and little else. Its two protagonists, Adam (Tom “Loki” Hiddleston) and Eve (Tilda “Orlando” Swinton who’s never been as beguiling and cuddly as she is here), are as deeply addicted to each other as they were when they met each other a century or two ago. They are also addicted to blood and lead fairly routine lives, maintaining their habits from mostly different spots on the globe; Eve wanders the curvy streets of Tangier, sheathed in silk, checking in on her vampire mentor Christopher Marlowe (John Hurt), who despite his disheveled state looks pretty hale for someone who was supposed to have been murdered at 29 years old in 1593 while Adam, a musical genius old enough to have given Schubert a hand, lives the gloomy-glam life of the reclusive rock legend inhabiting a ramshackle house in Detroit and collecting vintage guitars secured for him by a credulous idolater named Ian (Aaron Yelchin). Whenever Adam needs a supply of vintage O-Negative, he dresses up in surgical green, complete with mask and antique stethoscope, and sticks wads of cash in the hands of his connection (a droll Jeffrey Wright).