January 24th, 2020 — movie reviews

It will do no good to say, as we tend to do every year at about this time, that there are far more important things to think about than the damn Oscars. Of course there are. There always will be. The hum of impeachment hearings in the background as I’m writing this blog keeps pulling my attention away from such burning issues as whether Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is better than Jackie Brown (not quite) or whether Charlize Theron’s impersonation of Megyn Kelly is as scary or as bravura as Renee Zellweger’s of Judy Garland. (A hard “yes.”) But here I am asking myself these questions anyway and you know why, don’t you? Because you can be entertained by senate hearings for only so long and we go to the gauze of Oscar because we need escape hatches from solemnity.

The troublesome part comes in gauging whether the media industrial complex now cares more about the Academy Awards than movies. Moving pictures come and go through whatever delivery system we can imagine and we still wont know for another ten years which of these movies will last, or what we’ll even mean when we talk about movies in 2030. I am sure that no one will remember or care who wins what in a couple weeks because none of you (I bet) will remember who won what a year ago.

I do know this: a borderline-exceptional year for movies yielded, as I wrote someplace else, one of the least exceptional list of Academy Award nominations in years. Not that the movies themselves are bad. Quite the contrary. But this was a year so filled with quality pictures that the Academy could have taken more chances, nominated less-expected-but-just-as-worthy movies and actors. We can delve deeper into the MIAs as we always do: with a For Whatever It’s Worth (FWIW) blurb, whenever and wherever applicable.

The competition, as depicted below, is pretty much coated with chalk; in sports terms, this means prohibitive favorites with apparently unimpeded rides to victory, especially in the acting categories…maybe.

What I’m also sensing from this year’s assortment is a (somewhat) reactionary bent from an academy that may have gotten (somewhat) fed up with the hoops it’s had to leap through over the previous decade on matters of diversity, independent films and streaming services. If there were a comic-book superhero movie successful enough to be worth the trouble, members might not only have nominated it, but given it several key awards just to spite the cinema snobs.

Oh wait. There is, in fact, a comic-book supervillain movie showing signs of doing exactly that on the evening of February 9th.

Zounds! That means this thing is bearing down on us harder than usual this season. So why wait any longer to get to the picks? The future, in more ways than one, is now.

Best Picture:

Ford v Ferrari

The Irishman

JoJo Rabbit

Joker

Little Women

Marriage Story

x-1917

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood

Parasite

Director:

Martin Scorsese The Irishman

Todd Phillips, Joker

Sam Mendes, 1917

Quentin Tarantino, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood

x-Bong Joon Ho, Parasite

The Irishman looked like an early favorite heading into the season. But the suspicion here is that, as with Marriage Story, there’s just too damn much Netflix around this stuff for movie traditionalists to come to terms with. Roma had the same problem last year, along with English subtitles. This latter aspect would seem to disqualify Parasite, though its overall popularity is far broader than Roma’s ever was. Something tells me that, of all the rest, 1917 is exactly what we think of when we think of “Oscar bait.” It has all the elements: a big-screen narrative far more suited to theatrical than living-room viewing; technical virtuosity in service to a grandly mounted tribute to The Human Spirit (plus it’s a truly absorbing ride); and it has Sam Mendes, who carries the kind of cachet of Serious Adult Film Director that Fred Zinnemann, William Wyler or David Lean used to carry into battles for Oscar, even though I happen to think he’s closer to Zinnemann than to the other two. That Mendes already has one of these (2000 for American Beauty) won’t necessarily keep him from getting another. Lately, however, the splits between best film and best director have happened more often than they used to, and Parasite has connected so hard and deep with all kinds of audiences living life in the 21st century’s global economy that it’s not inconceivable that its director will be honored individually for it, along with the all-but-inevitable Oscar the movie will receive for what they’re now calling “International Feature Film.”

FWIW: Just for the record, my favorite movie of 2019 was The Last Black Man in San Francisco, which is the very antithesis of whatever “Oscar bait” means. I also would have been OK with The Irishman or Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood winning the top prize. But those two, I think, were made for the longer haul of historic debate, not for Oscar’s ultimate approbation.

Lead Actor:

Antonio Banderas, Pain and Glory

Leonardo DiCaprio, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood

Adam Driver, Marriage Story

x-Joaquin Phoenix, Joker

Jonathan Pryce, The Two Popes

Phoenix has specialized in desperate, marginalized men driven to erratic, often explosive (mis)behavior. He once played somebody with those traits named “Joaquin Phoenix” who showed up on David Letterman’s couch seemingly intent on setting his career on fire. Here he’s perceived as having gone “all out” with this persona and there’s nothing Hollywood likes better than honoring performances perceived as being “all out” as opposed to just “out there.” It will do no good to maintain that he was better in Inherent Vice or even The Master because those characters just, you know, bothered people. As God’s Lonely Guy who became Batman’s nemesis, he’s made marginalization palatable, even tamer, by ramping up the pathos and making The Joker (or is it now just “Joker”?) a surrogate for all those who feel left out. Which is no small achievement – and destined for the Academy’s enshrinement.

FWIW: Of course, I preferred the quieter and thus more unsettling alienation afflicting Banderas’ aging artist in Pain and Glory. And however much I became annoyed with Driver’s younger, more mercurial artist in Marriage Story, I believed him to be much more an embodiment of the present-day zeitgeist than Phoenix’s prancing sociopath. But I’d much rather talk about Eddie Murphy’s noticeable absence from this list. What happened? Was Murphy’s Rudy Ray Moore not outrageous enough? Or would the Academy have been more wowed if he’d done his own spin on Moore’s Dolemite character? Maybe there simply wasn’t enough room for Murphy – or, it would seem, for anything else connected with Dolemite is My Name, which may not have been the year’s best, but was a better and more revelatory movie than Green Book. And while I understand Adam Sandler’s relief over not having to wear a tux for a few more nights, he should have been in this mix for his nitro-powered jitteriness in Uncut Gems.

Lead Actress:

Cynthia Erivo, Harriet

Scarlett Johansson, Marriage Story

Saoirse Ronan, Little Women

Charlize Theron, Bombshell

x-Renee Zelwegger, Judy

As with Phoenix, Zellweger is this year’s exemplar of a performer going “all out,” specifically in an eerily on-point evocation of a stage-and-screen legend in decline. Also as with Phoenix, pathos has a lot to contribute to her big lead — and she does all her own singing, too. It’s such a compelling turn that almost everything else about the movie blurs around it. And this could be a problem for her. She wouldn’t be the first star whose movie ultimately lets her down. (It seems a recurring liability in biopics.) Because of this as well as some shade being thrown on her movie by Garland’s daughter Liza Minnelli, Zellweger’s lead is the one most vulnerable to an upset – though one wonders if a Scarlett Johansson win would be much of an upset. Hers is the performance on this ballot that grows on you the most with its emotional variety and tonal progressions. And the fact that she’s under Academy inspection for another performance in another category could enhance her chances here. Hollywood worships Judy Garland and admires anybody willing to do her justice. But to take a cue from Sally Field, Hollywood likes, really likes Scar-Jo and could show her how much they do in this category – or even in the other one. But we’ll get there soon enough.

UPDATE (2/6) — Forget Marriage Story. Not at all as beloved in L.A. whose residents, I sense, feel somewhat dissed by their depiction. It’s Zelwegger after all.

Supporting Actor:

Tom Hanks, A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood

Anthony Hopkins, The Two Popes

Al Pacino, The Irishman

Joe Pesci, The Irishman

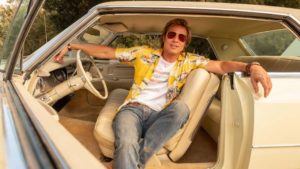

x-Brad Pitt, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood

I hope Pitt appreciates the magnitude of his competition. All the other guys have won before and been nominated more often. The thing is: Pitt does appreciate it, which is what makes him as lovable among voters as Johansson. Then again, they liked Sylvester Stallone, too and Mark Rylance picked his pocket (deservedly so) four years ago in this category. The same thing could very well happen here as this is the one category where acting chops are given heavier weight than in others. (Pesci or even Hanks could be the beneficiary.) Pitt’s performance, however, is a marvel of subtle grace and containment, verities of terrific screen acting that never – or practically never – are honored by Oscar whenever they surface. I’m still going with Pitt, but I think his triumph here will be a bigger “upset” than most believe.

FWIW: Would Christian Bale or Matt Damon in Ford vs. Ferrari qualify here or for lead actor? Either way, I’d have been happy to see one or both in this board game along with Wesley Snipes in his sneaky-great eccentric turn in Dolemite.

Supporting Actress:

Kathy Bates, Richard Jewell

Laura Dern, Marriage Story

x-Scarlett Johansson, JoJo Rabbit

Florence Pugh, Little Women

Margot Robbie, Bombshell

Dern is Hollywood royalty and Hollywood’s been waiting for an opportunity to reward her years of daring and diligence. Though I think her harder-than-it-looks work in Little Women was what should have landed here, her icy, commanding divorce lawyer is likely very familiar to most Academy voters and the shock of recognition alone could be enough to power her to the winner’s circle.

FWIW: Then again, Johansson’s performance as single mom to a Nazi brat in JoJo Rabbit is, as critics have observed, the luminous soul of the movie and if she doesn’t upset Zellweger in the lead category, she could very well pull it off here. (UPDATE (2/6) — I’m now thinking she will.) As for MIAs, my one-and-only here is Idina Menzel as Adam Sandler’s taking-no-shit-and-giving-negative-fucks wife in Uncut Gems

Adapted Screenplay

The Irishman, Steven Zaillian

JoJo Rabbit, Taika Waititi

Joker, Todd Phillips, Scott Silver

Little Women, Greta Gerwig

The Two Popes, Anthony McCarthy

Here is where the consolation prizes are usually given for those movies otherwise overtaken elsewhere and it’s where I think Irishman avoids getting skunked for the night – though either Joker or JoJo could take it away.

FWIW: The case has been advanced — though not, in my opinion, made – that Gerwig’s interpretation of Louisa May Alcott’s book errs too much on the side of modernist, or even post-modernist thinking, robbing the story of the warmth and magic that has sustained it through several previous adaptations. I can’t believe that the Academy carries similar qualms, but I suppose it’s as good an excuse as any to wave her along. I hope in any case that I’m wrong about this.

UPDATE (2/2) — Whoops! The WGA has spoken and it done fell in love with JoJo. Nobody said a motherin’ word about Irishman or Joker or any of Those People. I’m going with them, though it’s by no means a mortal lock.

Original Screenplay:

Knives Out, Rian Johnson

Marriage Story, Noah Baumbach

1917, Sam Mendes and Krysty Wilson-Cairns

x-Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, Quentin Tarantino

Parasite, Bong Joon-ho, Jin Won Han

Another strong field, and the tendency as always is to go with the dude with the smartest, freshest mouth in the pack. Johnson’s crafty script is a dark horse. But here is yet another opportunity to gauge the degree to which Parasite has become a global phenomenon.

FWIW: OTOH, if 1917 gets this, the night is essentially over.

Animated Feature:

How to Train Your Dragon: The Hidden World

I Lost My Body

xKlaus

Missing Link

Toy Story 4

Jérémy Clapin’s odyssey of a disembodied hand in search of its owner was one of the most original films of any kind this past year. Of course, this means it hasn’t a chance in hell of overtaking Buzz and Woody’s latest adventures. Curiously, though, any of the remaining three contenders could.

UPDATE (1/27) — And if the shockeroo pulled off by the “Annies” the other night is any indication, it looks as though it’s going to be the St. Nick origin story.

Best Documentary Feature:

American Factory, Julia Rieichert, Steven Bognar

The Cave, Feras Fayyad

The Edge of Democracy, Petra Costa

For Sama, Waad Al-Kateab, Edward Watts

x-Honeyland, Tamara Kotevska, Ljubo Stefanov

Despite the Obamas’ enthusiastic endorsement, American Factory likely wont overtake the near-miraculously rendered account of Macedonian beekeepers in conflict over the future of their ancient trade – and in a larger sense, the future of the planet. That it’s also nominated in the category just below speaks to its preeminence.

Best International Feature Film:

Corpus Christi

Honeyland

Les Miserables

Pain and Glory

x-Parasite

Sorry, Maestro Almodóvar. But the South Korean juggernaut, as dark and wild as anything you’ve wrought in the past, is too strong for your masterly elegy to overpower.

FWIW: I was sort of hoping for some love here for Mati Diop’s haunting, allusive Atlantics.

Cinematography:

The Irishman

Joker

The Lighthouse

x-1917

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood

Robert Richardson’s orchestration of sunlight and shadow in Once Upon a Time… is invaluable in achieving a sense of a lost world that almost, but never, was. I’m rooting for him, but guessing that Roger Deakins will repeat a year after his long-denied first-time win.

Original Score:

Joker

Little Women

Marriage Story

1917

Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker

Some hallowed names – John Williams, Alexandre Desplat, Randy Newman, Thomas Newman – are assembled here and they all showed up and produced big-time. Nevertheless it’s the relative newcomer — Hildur Guðnadóttir – who scores big on her first try.

Original Song:

“I Can’t Let You Throw Yourself Away,” Toy Story 4

x-“I’m Gonna Love Me Again,” Rocketman

“I’m Standing With You,” Breakthrough

“Into the Unknown,” Frozen 2

“Stand Up,” Harriet

If anybody is going to beat a drama-laden rouser from the Frozen machine, it’s Sir Elton, who even at or near his dotage can out-rouse anybody who throws down the spangled gauntlet.

December 31st, 2019 — movie reviews, on writing lit -- and unlit, TV reviews

Another year for people to hurry along into the dustbin – and the one just ahead doesn’t look at the outset to be much better, at least politically. But culturally at least, 2019 was a whole lot better than one comes to expect in Times Like These. So maybe pessimism about the immediate future is misplaced, though I’m keeping my cards hidden for now. Whatever the future holds, here once again is my own private top-ten of everything that got a rise out of me in the past year. And once again, they are in no particular order:

The Last Black Man in San Francisco – It’s been a long time since I’ve seen a movie three times in the same year, much less have it grow inside my head with each viewing. The first time I saw it, I came away thinking of it as a lyrical, idiosyncratic meditation on the cumulative impact on gentrification and the ways it has, over generations, shattered whatever meaning to be found in the words, “home” and “roots.” The second time I saw it, I listened closer to its dialogue, its depiction of families vulnerable to fault lines of denial, delusion and not-so-benign neglect. For whatever reason, the third viewing brought out in sharp relief the speech by budding playwright Montgomery Allen (Jonathan Majors) about the violent death of a friend and how whole lives, especially those belonging to young black men, are so often put in boxes by others and how it’s left to those young men to break out of those boxes by themselves. It made me think of boxes I’d been forced to occupy and bust open on my own throughout my life and, in the context of Joe Talbot’s debut feature, I started to wonder, with some distress, whether home, or even the desire for home, made up a kind of box that constrains one’s best aspirations. I bet if I watched it for a fourth, fifth and seventh time I’d start thinking of other, different things to unsettle me. No matter how many times I see it, the one line that’ll stay with me belongs, appropriately, to Jimmie Falls, the movie’s star and co-screenwriter, who gently chides a bus-riding sourpuss for bad-mouthing the home town that’s picked him up and slammed him down: “You don’t get to hate it, unless you love it.” Some movies are too small for the thoughts that contain them. But this movie has a soul big enough to set free hundreds of dreams, whether renovated or built from scratch.

Watchmen – “I’m not a Republic serial villain,” Adrian Veidt/Ozymandias insists in the original 1986-87 Alan Moore-Dave Gibbons graphic novel just before he makes millions of heads explode in New York City. Damon Lindelof’s sequel/reinvention for HBO made America’s heads explode by fashioning a harrowing version of a 1940s Republic movie serial spiked with sex, drugs and sociopolitical science. Among the many miracles of this brash and daring venture, the most noteworthy may be how it shares with its source material the way it weaves pulp mythology of costumed vigilantes into an oddly plausible version of 20th century history, leaving us all in pretty much the same sorry, disheartening mess we’re in at the precipice of true-life 2020. On a far less cosmic level, I have along with many others in the Twitter-verse found among many new reasons to love Regina King the way her character says “motherfucker” with the sweep and precision of a nothing-but-net three-pointer.

On The Media – I’ve long stopped watching nightly newscasts and would just as soon skip whatever the 24-hour news cycle has to offer at any given interval. But for the sake of whatever sanity I can maintain when dealing with the awfulness of the present, I never miss WNYC’s inquiry into all things media. Week after week, co-hosts Brooke Gladstone and Bob Garfield, along with their doughty support team of editors and producers, manage, with probing intelligence and gimlet-eyed scrutiny, to get at whatever’s been bothering me about the way things are and – mostly – aren’t covered by what we used to call “the press.” They are the go-to source for slicing and dicing though the smoggy mendacity of the Trump administration and its enablers. They secure your trust by chasing down truth, lies and, most of all, context. It isn’t enough, for instance, to say that the justice system is dysfunctional. So they will give you the historical factors – cultural, political and racial – behind mass incarceration. And not just that issue, but also poverty, climate change, education, foreign policy and housing. The program’s signature achievement in this especially estimable year was its series on “The Scarlet E,” as in “eviction,” one of many stories festering in post-Millennial America that doesn’t get as much attention in the media biosphere as, say, whatever Bill Gates is or isn’t doing with his money – even though they’ve got that covered like a blanket too. More than most of the media it holds accountable, this series fulfills the basic requirement for delivering the news by telling you things you didn’t already know and reminding you of things too important to forget.

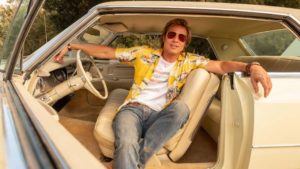

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood & Dolemite is My Name – If I owned a repertory house or a drive-in, I would make these a double feature that I made sure to exhibit every year (late summer, I think). Though they’re set a few years apart from each other near the hinge of the 1960s and 1970s, both movies appear to be conversing from opposite ends of the culture about a transformative era for American movies. Traditions that were either falling apart or recombining in Quentin Tarantino’s iridescent alternate history of 1969 were pulled from back alley trash compactors by the working-class L.A. schemers and dreamers brought to merry life by director Craig Brewer and screenwriters Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski. The reinvention of Rudy Ray Moore (Eddie Murphy in what some keep insisting is a “comeback” even though he’s never really gone away) gives off a giddy vibe of a rags-to-raggedy-ass-riches saga, a kind of lounge-lizard’s version of Up From Slavery with an upraised middle finger goading you to eat its dust. Once Upon a Time…is in a starkly different manner a Pilgrim’s Progress saga, though you’re left wondering at the end whether it’s Leonardo DiCaprio’s has-been TV western hero or Brad Pitt’s deceptively blithe stuntman-handyman who’s made the most progress. Such questions matter more than whatever conclusions some have extracted from Tarantino’s vision – and it is more than anything a vision, whatever you want to make of its depictions of both imaginary and real-life characters.

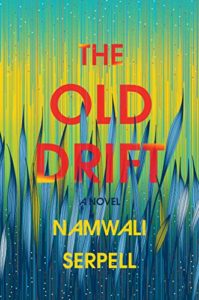

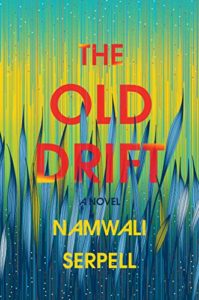

The Old Drift – My favorite novel of the year is best described by its author Namwali Serpell as “the great Zambian novel you didn’t know you were waiting for.” It begins with an implausible accident at the start of the 20th century involving three individuals in a hotel along the Zambezi River in what was then known as the Northwestern Rhodesia territory. The lives of their families – one African, one British, one Italian – are intertwined for what’s left of that century and for several years into the 21st. In between, there are sagas within sagas; some dealing with a woman’s hair that cannot stop growing and whose fallen strands make things grow out of the ground. Another story arc is based on the true-life effort by Zambia’s “Minister of Space Research” to train his newly independent nation’s best and brightest science students to beat both the Russians and Americans to the moon before the end of the 1960s. Eventually the tangled destinies of these and other characters are swept up by a public health calamity referred to here as “The Virus.” Serpell’s novel dares to imagine her native country into a technologically advanced near-future that is at once exhilarating and frightening in its prospects. Add to all this the constant presence of mosquitoes as both a kind of Greek chorus and vigilant corporate godhead and you have a willfully imaginative and (I almost forgot to add) gorgeously written contribution to the shelf of such novels as The Tin Drum, One Hundred Years of Solitude, Midnight’s Children and (wothehell) Adventures of Huckleberry Finn that realize a whole country’s heritage and destiny in a rich, capacious fictional narrative. I also forgot to mention that this is Serpell’s first novel.

Kristen Scott Thomas on Fleabag — There was a lot to love about the second season of Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s universally-acclaimed series, beginning (of course) with Waller-Bridge herself and her bemused, stressed-out and agreeably horny alter-ego stumbling and grappling through her fraught early thirties. I was all in on her Fleabag persona throughout her search for love, even if the approach-avoidance thing with The Priest (Andrew Scott) began to grate for reasons having nothing whatsoever to do with its presumptive “impropriety.” For all its humane and bittersweet wit, the series, for me, glowed brightest in the approximately five minutes Fleabag spends in a bar with Belinda (Thomas), a corporate mogul fleeing a cocktail party in her honor. Over martinis, Belinda gives Fleabag – and us – the gift of her wisdom about things like menopause, why women are better able to deal with pain than men and the categorical imperative to flirt. Never before have I (and, I’m betting, anybody else I know) seen Kristin Scott Thomas so juicy, so fired-up-funny and lit-from-within as she is here. No wonder Fleabag makes a pass at her. We all would. But instead of a tumble, Belinda bestows to Fleabag something more precious by declaring, “People are all we’ve got.” And in case you didn’t hear her, she repeats, “People. Are. All. We’ve. Got.” Much as you don’t want to agree (and almost everything else about the series encourages you not to), you know, deep down, that she’s right about this, along with everything else she’s laying down.

Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story – A word to those who insist on believing that Martin Scorsese’s meta-mixing of imaginary sidebars to the actual Rolling Thunder tour conducted by Dylan during the Gerald Ford administration is somehow contiguous to the “fake news” ethos abetted by the Right. That word is, to be polite as possible about it, no. The movie states its business at the outset: what else would an old magic trick be doing there? If you can’t tell from jump street that it’s playing fair with its variations on a theme, that’s on you, not on Scorsese and not on Dylan. I may disagree with the latter’s typically gnomic pronouncement that wearing a mask is a means of telling the truth. (As with much else with Dylan, he borrowed that observation from someone else; Oscar Wilde. I believe, in this case.) But the movie’s mischief is nonetheless consistent with a rock music tour whose whole concept was steeped in shadows, disguise and craftiness. Those whoppers with Sharon Stone and Jimmy Carter may rankle the literal-minded. For me, the movie’s willingness to tease at and toy with the parameters of literal and figurative storytelling is far less a concession to the present-day political madness than a provocative means of climbing out of the smog. To elaborate: I remember going to a November 1975 Rolling Thunder gig at the Hartford Civic Center deep in the doldrums of economic blight, especially in down-and-depressed New England, and coming away from the show feeling buoyed and even cross-eyed hopeful about the immediate future. Which is sort of how I felt when this movie was over. I can’t tell you why any more than I could explain my reaction back in the day. It may have something to do with being more open to possibility and risk than to cloistered indignation and fear. Or maybe it has something to do with whatever Allen Ginsberg is telling us all to do at the end of this film: “You who saw it all or who saw flashes and fragments, take from us some example, try and get yourselves together, clean up your act, find your community, pick up on some kind of redemption of your own consciousness, become mindful of your own friends, your own work, your own proper meditation, your own art, your own beauty, go out and make it for your own Eternity.” Now you tell me: what does any of this have to do with whether something is fake-fucking-news or not?

In the Dream House – Imagine a warm-hearted Patricia Highsmith who retains enough delicacy and detachment to train upon herself as well as those around her. But Carmen Maria Machado’s not writing a thriller – or more to the point, she’s not writing just a thriller. Her memoir of a psychologically abusive relationship with another woman inhabits multiple genres and motifs. Its chapter headings conceive segments of this story, by turns, as a “road trip to everywhere,” or “bildungsroman,” “lesbian pulp novel,” “creature feature,” “comedy of errors,” “sci-fi thriller,” “soap opera,” “American gothic” and “stoner comedy.” There are also categories such as “hypochondria,” “dirty laundry,” “word problem,” “queer villainy,” “Chekhov’s gun,” “house in Iowa,” “apartment in Philadelphia,” “second chances” and so on. Maybe you can figure out a narrative of sorts from these clues. But Machado is not only engaging openly and honestly with personal pain, but probing for different ways to articulate it. In the process, she reinvents “memoir” itself as an arena for scholarly speculation, cultural inquiry, links to folklore, fairy tales and even an especially grisly episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation. She is using all her imaginative resources to get to the kind of truth promised, but intermittently achieved in more conventional memoirs. Besides Highsmith, you think of W.G. Sebald and Raymond Queneau and their experiments with narrative and reminiscence. The real thrill one feels in reading In the Dream House is in encountering a means of personal storytelling that is original and, in more ways than one, transformative.

Russian Doll – Nadia (Natasha Lyonne) is a brittle, habitually grouchy New Yorker who’s in a unique rut. She keeps coming to at the same birthday party at a friend’s apartment, leaves and, in some way or another (falling down stairs, struck by a car, blown up by a gas stove, etc.), dies soon after, only to find herself immediately getting ready to leave the same party and the same apartment for yet another “Appointment in Samarra.” So far, so “Groundhog Day.” But this Netflix series is different in many ways, not least because eventually Nadia finds that she’s not the only one going through this. “I die all the time,” a guy named Alan (Charlie Barnett) tells her as the elevator car they’re sharing is about to crash to the ground. So now they’re each other’s chronic-death buddies, roaming the streets of Lower Manhattan in search of clues, patterns, some kind of rational explanation for their shared predicament before one or both of them get killed again. Somehow this feels less like a “Groundhog Day” variation than a post-9-11 version; one where New Yorkers feel stalked and at times overcome by the prospect of death from anywhere, but are somehow more intensely in pursuit of life. What makes this more than a clever conceit is Lyonne’s magnetic presence. As with everything she does, Lyonne combines the brassy tempo of a thirties screwball-comedy heroine with the brainy poise of a fifties TV private eye. She keeps us on the edge of our seats even though we know she’s never really going anywhere. At least, we hope not.

Little Women – Louisa May Alcott’s novel is so durable and well-crafted that it’s next-to-impossible to make a bad movie out of it, even if you were trying hard to do so. The challenge, however, comes in trying to find new ways of telling the story that doesn’t mitigate its power to charm and move its audiences and Greta Gerwig, of whom I said two years ago (Lady Bird) had the stuff to be a great director, has deftly rearranged the March sisters’ saga into fragments that shift back and forth through time. You notice Gerwig’s innovations without being in any way thrown by them and the glue holding these elements together are the uniformly superb performances, perhaps the most subtly remarkable of which is Laura Dern as Marmee, who is at once remote and warm, imperious and giving; able to contain what she concedes is a deep well of anger over her circumstances while wearing her circumspection as though it were her own battle uniform. Gerwig’s film arrives at year’s end like an unexpectedly bountiful gift to her audiences, emotionally accessible, yet quirky in parts, especially in those dance sequences. But Gerwig does love dance and she’s learning how to make her craft move to its own rhythms.

And now, as a public service to at least two people who’ve asked me about it, my own private top-ten movies of the 2010s. Once again, as with the preceding inventory, these are in no particular order. They are also submitted with no additional comment beyond those you’ll (probably) find elsewhere on this site:

Moonlight (Barry Jenkins)

Toni Erdmann (Maren Ade)

Phantom Thread (Paul Thomas Anderson)

Only Lovers Left Alive (Jim Jarmusch)

Mad Max: Glory Road (George Miller)

Get Out (Jordan Peele)

Hell or High Water (David Mackenzie)

Lincoln (Steven Spielberg)

Cold War (Pawel Pawlikowski)

Moonrise Kingdom (Wes Anderson)

BEST DOCUMENTARY: The Act of Killing & O.J.:Made in America (tie).

BEST ANIMATED FEATURE: Spider-Man: Into the Spider Verse & The Shaun the Sheep Movie (tie).

BEST SUPERHERO MOVIE: See directly above.

FILMMAKER OF THE DECADE: Paul Thomas Anderson

December 7th, 2019 — family history, jazz reviews

I’m not going to say this past year in jazz was stranger than any other. But my list is sure a surprise, at least to me.

I mean…just look at the top five…not just one, but two organ albums? Yes…and not only that, they were both different approaches to jazz organ, having little in common except some righteous tenor sax interaction and all-out commitment from their respective leaders. More on them later.

It makes me remember something told to me back in the 1980s by a very wise man named Jerry Gordon, founder and manager of Philadelphia’s hallowed and still much lamented Third Street Jazz: “There’s no middle ground on organs. People either love them or they don’t.” Jerry would know since Philadelphia has a legitimate claim to being “the jazz organ capital of the world” and indeed, one of the organists on this list has deep Philly roots, deeper even than those of Sun Ra, another organ player who called Philadelphia home and whose massive, unparalleled body of work Jerry would later help curate for Evidence Records.

If anybody occupied Jerry’s nonexistent middle, I was sure it was me, even if I could never avoid such music because as far as my dad was concerned, organ jazz was Dah Joint. This was especially true in the 1960s when he was looking for something to make the rec room jump at odd hours of the night. Jimmy Smith, Jack McDuff, Groove Holmes, Charles Earland, Shirley Scott…those were all his peeps, his boon pals and drinking buddies. Not that I didn’t jump up and down to Jimmy Smith by my own self in those years, but I had so many more outlets for musical comfort and joy. So “love,” as Jerry characterized it, had little to do with it.

Still, as much as Dad would find the basic trappings cozy and familiar, I can’t say for sure whether he’d be able to hang long with these two organ albums. They swing hard, but they also aim high. As much as he liked to jump, Dad likely wouldn’t want to go as high as these two albums. As I say, more on them later.

I suppose that having jazz organ front center aligned somehow with a need I had from jazz and from culture in general to go hard and aim directly at the heart of things. The music that grabbed me the most this past year didn’t dwell on stuff too much, but showed commitment, energy and drive. In plain terms, these albums all followed the ancient bandleader’s imperative to “Hit It!” And that was enough for me.

There was too much else to think about this past year – and also not a whole lot of thinking to go with it. So, if passion was there to be had, my sense of things was that it had better be engaged, tough and above all smart to know where it was going and how it wanted things said and done.

So, let’s hit this!

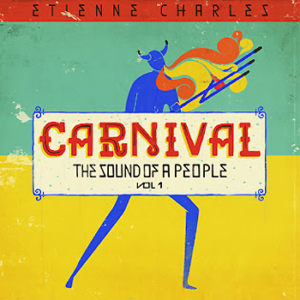

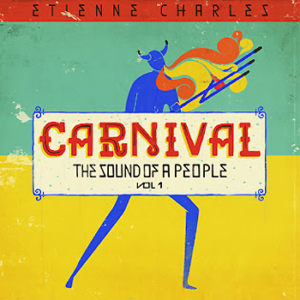

1.) Etienne Charles, Carnival: The Sound of a People, Vol. 1 (Culture Shock) – I like gumbo. No, I don’t. I love gumbo. I especially love it when its ingredients are scraped, plucked, dug up, mashed, dashed and liberally strewn into the pot with seeming abandon, but also – and always – with instincts homed in on what combinations will at once surprise, awaken and enchant the senses. Charles, a trumpet tyro from Trinidad, has made it his business to collect musical seasonings and spices from all over the Caribbean to create mind-body release music redolent of their cultural origins while intent on illuminating the region’s complex history. His previous work, including 2013’s Creole Soul and 2017’s San Jose Suite, gave off rushes and thrills while disclosing the calculation and intelligence behind them. On Charles’ full-bore inquiry into the festival music of his native land, the erudition isn’t as conspicuous, but the eclecticism is. And the rush invigorates from the jump as an on-site recording of Trinidadian street musicians laying down a rollicking, swiveling beat is amped up by some slash-and-burn post-bop inventions of Charles, also saxophonist Brian Hogans pianist James Francies, guitarist Alex Wintz, percussionist D’Achee and drummer Obed Calvaire and others. David Sanchez adds his agile tenor sax to the simmering pot on other tracks and the leader himself kicks in some percussive support, even a cowbell, to the proceedings. This is the enrapturing and beautiful album one long suspected Charles is capable of delivering and maybe the best part of the whole deal is that this is only “Vol. 1.” Here’s my bowl. More, please.

2.) James Carter Organ Trio, Live from Newport Jazz (Blue Note) – It’s been almost twenty years since Carter, a fire-breathing, bottom-voiced avatar of croon-and-holler saxophone, last took a deep dive into the repertoire of gypsy guitar legend Django Reinhardt. And it’s been almost ten years since he’s released an album of any kind. As if to remind us of what we’ve been missing, Carter audaciously re-engages with Reinhardt’s music and brings along his power backup of organist Gerald Gibbs and drummer Alex White. Thus, two raucous traditions – the red-hot “jazz manouche” of 1930s-1940s Parisian bars and the smoky-blue hardbop of 1950s-1960s uptown nightclubs – were in each other’s arms at Carter’s 2018 Newport Jazz Festival appearance and the clinch proved intoxicating, even transformative. Unlike 2000’s Chasin’ the Gypsy, Carter’s not here to pay homage, but to revitalize such Reinhardt chestnuts as “Le Manoir De Mes Reves,” “Anouman” and “Melodie Au Crepuscule” with soulful strutting and hard-rock shouting. The trio opens “Crepuscule” with a grinding vamp borrowed from Bill Withers’ “Use Me,” drawing the crowd to their side and keeping it in their pocket with Gibbs’ spirited riffing and Carter’s bait-and-switch inventions. While Carter can still blow the doors off any nearby building with his sky-scraping honks, bleats and wails, his deep tone on tenor, alto and soprano sax is supple and lustrous at any tempo or altitude. The smoldering, bewitching variations he makes on “Pour Que Ma Vie Demeure” induce both terror and awe and apply a diamond-hard exclamation point to this triumph for Carter, for Newport and for tradition, wherever it can be salvaged and recombined.

3.) Branford Marsalis Quartet, The Secret Between the Shadow and the Soul (Marsalis Music) – Through the years, nay, decades he and his family have held presumptive dominion over the national jazz discourse, Branford has always been my favorite Marsalis grumpy-pants: testy, feisty, dryly funny and brazenly confrontational with his peers over what jazz music really is and what the public really wants from it. Whether in dispute or agreement with his tirades, I’ve often found them livelier than his music, however solidly crafted and polished in presentation. There’s been no doubt that he and his bandmates – pianist Joey Calderazzo, bassist Eric Revis and drummer Justin Faulkner – have as keen a rapport with each other and with their audience as any working combo. But there hasn’t been a full-blown album that evokes what this rapport can achieve at its best. Until now. Something about this one pulls hard on your coat and ramps up the unit’s commitment and drive. Every member brought their A-game for this session to the point where it’s hard to single out, say, Calderazzo’s sweet, steady-rolling changes on his pieces “Cianna” and “Conversations Among The Ruins,” or Revis’ combustible compositions, “Dance of the Evil Toys” and “Nilaste.” Faulkner, the relative newbie in the group, contains and advances the apparatus with a fiercely applied command of weight and balance belying his youth. And the leader seems more locked in than usual, playing with blazing verve and urgency that enhance his habitual ingenuity. To get the full impact of this group’s high-spirited interaction, you need only listen to its exuberant rendition of Keith Jarrett’s “Windup” that, appropriately, brings this set home. Many moons ago, Marsalis showed his drolly churlish side speaking of Jarrett’s own prickly-pear personality, insisting even then that he had nothing whatsoever against Jarrett’s music, proving that even the hardest-shelled curmudgeons can call upon their generosity when properly inspired.

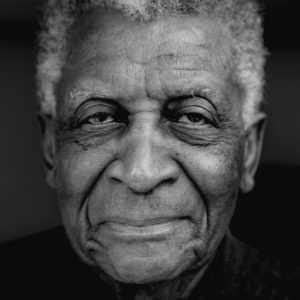

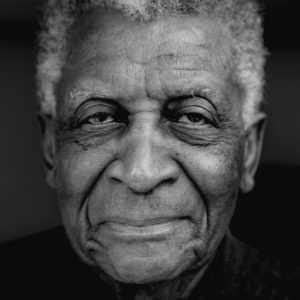

4.) Abdullah Ibrahim, The Balance (Gearbox) – At 85, South Africa’s greatest living jazz artist finds himself deep in the winter of…not discontent exactly, but of wistfulness that stops just short of melancholy. His piano still dances with as much command of space and time as it ever did. But it now takes its time, forsaking much of the whirling-dervish momentum of Ibrahim’s youth with a more deliberate pace that nonetheless resolutely forsakes caution. The sepulchral mood of “Dreamtime” at first throws you off. But as soon as his seven-piece band Ekaya kicks in full gear on “Jabula”, Ibrahim gets frisky enough with the beat to let you know he’s nowhere near ready to slip into the shadows. He remains as open to riding the rugged and unfamiliar in rhythmic combinations as he ever was and as moving as his performance is of “Song for Sathima,” the paean he wrote for his late wife, vocalist Sathima Bea Benjamin, there’s a grand and open-hearted spirit to the recital that envelops multitudes. Now more than ever, it’s possible to hear — and feel — what got Duke Ellington all het up when he first heard the Artist Formerly Known as Dollar Brand (a name he still uses on the cover of this one, though not as prominently).

5.) Joey DeFrancesco, In the Key of the Universe (Mack Avenue) – When I first saw him as a student at Philadelphia’s Settlement Music School, he was still “Joe DeFrancesco” pounding the hell out of an acoustic piano as if his life depended on it. (The kid playing electric bass behind him was then known as “Chris McBride.” As you’ve heard, his grown-up self is likewise better known under another first name.) Joey went on to follow in his dad’s footsteps on the Hammond B-3 and became keeper of the jazz-organ tradition. This album takes his talents to an unexpected direction and, as much as I’d detected way back in his prodigy period, he seems to be going all-out on this one, using all his considerable resources to probe the mystical and spiritual realms explored by African American jazz artists of the late 1960s and early 1970s. He even brought along Pharaoh Sanders, one of the key figures of that movement, to sit in on a couple of tracks, and damned if the 79-year-old Sanders doesn’t sound here as nimble and propulsive as he did in his “Karma” period. (He even takes the late Leon Thomas’ role in singing the lyrics to “The Creator Has a Master Plan.”) DeFrancesco’s regular saxophonist Troy Roberts plays with similar force and grace and it’s always a treat to hear Billy Hart on drums with Sammy Figueroa ably in support on percussion. But as usual, it’s the leader you can’t wait to hear whether he’s vamping and swinging with deceptive ease, comping with dexterity or surging through the changes with near-demonic energy – though on second thought, “near-demonic” (a compound I think I used when I first wrote about him in his middle school days) is an inappropriate characterization for such a spiritually-based enterprise. Bright moments.

6.) Miguel Zenón, Sonero: The Music of Ismael Rivera (Miel) –– Rivera (1931-1987), also known as “Maelo” or “El Sonero Mayor,” was a genius of salsa singing, a master of antiphonal improvisations spinning choruses within, through and above choruses with such groups as Los Cachimbos and Cortijo y su Combo, table-setters for bomba and plena genres. This makes him an inevitable and fertile subject of inquiry for Zenón, who has dedicated himself to framing and extending the motifs to his native land’s pop music with modern jazz motifs. Once again, Zenon, pianist Luis Perdomo, bassist Hans Glawischnig and drummer Henry Cole find fresh, ingenious and uplifting possibilities from their source material without in any way mitigating its subtle graces. Their effervescent interaction is bracing at any pace, whether in the somber dirge “Las Tumbas” or in the rough-and-tumble “El Negro Bembón” with its rapid-fire quintuplets. As effectively as the rhythm section tamps down each eccentric shift in tempo throughout the album, it’s Zenón’s alto saxophone, by turns fiery and elegiac, that most enraptures in conspicuously, appropriately assuming lead vocals.

7.) Steve Lehman Trio with Craig Taborn, The People I Love (PI) – Put an intense maximalist like alto saxophonist Lehman together with a dedicated minimalist like pianist Taborn and you get…well, is “harmony” the word we’re aiming for here? Probably not since the word assumes they meld with their personalities fully intact. Their give-and-take on “In Calam & Ynnus” suggests at the very least a mutual affinity for ripping stuff apart and slamming the distended shapes back together into odd, but logical coherence. Lehman’s facility for rapid-fire riffing is taken up by Taborn, who is willing to fade their discourse out and let Taborn carry the rest of their colloquy home. Here, even more than on his previous albums, Lehman’s bright, bristly tone proves adaptable to a variety of contexts, whether it’s Autechre (“qPlay”) or Kenny Kirkland (“Chance”). He seems most empowered by a burner like Kurt Rosenwinkel’s “A Shifting Design,” where he, Taborn, bassist Matt Brewer and drummer Damion Reid weave into each other’s embroideries so well that you can’t always tell who’s keeping time. (All of them. likely.) This, to me, is the warmest, sunniest album yet from Lehman and, for that matter, from Taborn. Once again, I’m hoping for seconds.

8.) Nicholas Payton, Relaxin’ with Nick (Smoke Sessions) – As a colleague said to me the other day, Payton may not appreciate being on this list at all, given his contempt for the word “jazz.” He prefers the acronym, “BAM” for “Black American Music” to define what he does. As if to drive the point home, the album includes his composition, “Jazz is a Four-Letter Word,” inspired by the title of Max Roach’s unpublished autobiography and if you want to know what he and Payton mean, the late drummer’s recorded voice is there to explain, both in full and in sampled bits. It’s one of the highlights of this two-disc live trio recording, an unvarnished triumph of multi-tasking as the one-time trumpet prodigy proves himself to be a master of acoustic and electronic keyboards, capable of even comping his horn solos, which are as powerful, vibrant and pulsing with narrative energy as ever. (His singing of “Othello” and “When I Fall In Love” isn’t as masterly, but his downy phrasing suggests he’s on to something nonetheless.) One suspects he’d try being his own rhythm section someday. But at least for this laid-back marathon session, he is fortunate to have bassist Peter Washington and drummer Kenny Washington at his back. They’re not related to each other, but share years of veteran savvy, impeccable timing and implacable focus. As with the Marsalises, Payton isn’t shy about courting controversy and he has in like fashion used whatever rancor he arouses as fuel for his forward progress. However you feel about his pugnacity, he’s at peace with it – and you should be, too.

9.) Wadada Leo Smith, Rosa Parks: Pure Love (TUM) – The peerless and, at 77, apparently tireless Smith previously paid tribute to Rosa Parks and the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott seven years earlier in his epochal opus Ten Freedom Summers. He takes what he characterizes as the boycott’s “381 Days of Fire” and unfurls from its core an oratorio in Parks’ honor with seven songs, three singers (Min Xiao-Fen, Carmina Escobar, Karen Parks), a string quartet, a brass trio (including Smith’s trumpet), two percussionists and some electronic sound mixing. Smith also augments this blend with excerpts from recordings he made about fifty years before with fellow “creative music” insurrectionists Anthony Braxton, Leroy Jenkins and Steve McCall. The music may not be “easy,” but its message is elemental: a plea for simple justice in the face of fear and loathing. Not to put too fine a point on this, but given the imperatives of the present day, such a testament would be worth the investment of those who are closest to you – and especially those who aren’t.

10.) Paolo Fresu, Richard Galliano, Jan Lundgren, Mare Nostrum III (ACT) – One of the treasures of European jazz has put out three gorgeous albums in more than a decade and still aren’t as famous as they should be on these shores for emitting some of the most transfixing sounds on the planet. The great Galliano (as I’ve come to call him, mostly because it sounds cool) remains a formidable paragon on the accordion and related gadgets. But what’s become apparent over time is how he’s made his virtuosity merge so seamlessly with Fresu’s plangent horn and Lundgren’s dulcet keyboard. They collectively merge their distinctive voices so as to now seem to speak as one delicate, riveting entity. Both the familiar (“Windmills of Your Mind,” “Love Theme from ‘The Getaway’”) and the not-so-familiar (Lundgren’s “Ronneby,” Galliano’s “Letter to My Mother,” and Fresu’s “Human Requiem”) are rendered in short takes, densely packed with rich melodic invention and tightly contained passion. Some might dismiss it all as “pretty,” but you can pass by “pretty” with ease. These guys make the kind of terrifyingly beautiful music that stops you in your tracks if you’re not careful.

HONORABLE MENTION : Steve Davis, Correlations (Smoke Sessions), Anat Fort Trio, Colour (Sunnyside), Matthew Shipp Trio, Signature (ESP)

Ed Palermo Big Band, A Lousy Day in Harlem (Sky Cat), Anat Cohen Tentet, Triple Helix (Anzic)Toni Freestone Trio, El Mar de Nubes (Whirlwind)

Fabian Almazan Trio, This Land Abounds with Life (Biophilia)

BEST VOCAL ALBUM

Catherine Russell, Alone Together (Dot Time)

HONORABLE MENTION; Annie Addington, “In a Midnight Wind” (Annie Addington)

BEST LATIN ALBUM: Miguel Zenón, Sonero

HONORABLE MENTION: Guillermo Klein & Los Guachos, Cristal (Sunnyside)

BEST HISTORIC ALBUM

Eric Dolphy, Musical Prophet: The Expanded 1963 New York Studio Sessions (Resonance)

Stan Getz, Getz at the Gate: The Stan Getz Quartet Live at the Village Gate, Nov. 26, 1961 (Verve)

Gerald Cleaver & Violet Hour, Live at F1rehouse 12 (Sunnyside)

November 6th, 2019 — on writing lit -- and unlit, Politics & Other Disappointments

Of all those who’ve had their say, and then some, about Albert Camus, A.J. Liebling likely came closest to summing up his essence when, in a footnote to one of his columns about what we used to call, “The Press,” he wrote that Camus’ energies “were dissipated in creative writing and we lost a great journalist.”

Except I’m not as sure as Liebling was that we “lost” Camus as a journalist. If anything, I’m thinking that in the almost 60 years since Camus was killed, at 46, in the crash of his publisher’s sports car, he’s come into even greater definition as a writer whose nonfiction, most especially his journalism, has more to tell us these days than the novels, stories and plays that forged his reputation during his lifetime.

He was often classified as a philosopher and this seems to me as misapplied as using the same word to describe Norman Mailer. At their respective peaks, both were remarkable, relentlessly penetrating observers, not only of their own psyches, but also of whatever energies were swirling around them. One need only read some of Camus’ Lyrical and Critical Essays published posthumously in 1968 and the intensely rendered landscapes of Prague, Oran, Algiers and the Mediterranean to see how he could put a reader alongside him in the places he describes. You also see this fidelity for pertinent detail in his last novel, The First Man as he vividly evokes what it looked, sounded and even smelled like to be in the houses, neighborhoods and schools of his childhood.

Tagging Camus as a journalist, however, may seem to devotees a kind of demotion from being the globally revered “conscience” of the Western world. A review of Herbert Lottman’s 1979 Camus biography suggested that the book made its subject sound more like “a species of ballasted newspaperman, a French James Reston.” Clearly this wasn’t meant as a compliment to Lottman, Camus or Reston. (And, by the way: “ballasted”?) All those iconic photos of a brooding Camus in an open trench coat, a cigarette dangling Bogart-ishly from his lips seal this overall impression, adding noir-ish glamour and affirming to some that there was less than met the eye to Camus’ philosophical repute.

His journalistic repute, however, remains to me valuable and important. His was the kind of skeptical mind that was even skeptical towards its own skepticism. Journalists insist that this is a worthwhile quality in the abstract; in the workaday world, however, it’s seen as an immobilizing liability. Can’t keep second-guessing yourselves, people! Got to nail something down before deadline.

When he nailed things down, Camus was unequivocal and the impact was, if anything, only amplified by the pitch and yaw of his self-inquiries, especially when it came to such subjects as capital punishment (which he was forcefully, persuasively against) and resistance against World War II Nazi occupiers and Vichy collaborators alike.

There’s a shock of recognition to be found on the first page of Camus and Combat: Writing 1944-1947 (Princeton University Press), a collection of his journalism for the French Resistance newspaper for which Camus served as editor-in-chief and editorial writer. In March 1944, the 55th edition of Combat ran his editorial, “Against Total War, Total Resistance.” If you’ve been alive and aware over the last few years, the following excerpts are going to feel…eerie to read:

“Lying is never without purpose. Even the most impudent lie, if repeated, often enough, and long enough, always leaves a trace. German propaganda subscribes to this principle, and today we have another example of its application. Inspired by Goebbels’ minions, cheered on by the lackey press, and staged by the Milice [a French militia backing German efforts to put down the Resistance], a formidable campaign has just been launched — a guise which seeks, in the guise of an attack on the patriots of the underground and of the Resistance, to divide the French once again. This is what they are saying to Frenchmen: ‘We are killing and destroying bandits who would kill you if you weren’t there. You have nothing in common with them.’

“Although this lie, reprinted a million times, retains a certain power, stating the truth is enough to repel the falsehood. And here is the truth: it is that the French have everything in common with those whom they are today being taught to fear and despise…

“Don’t say, ‘This doesn’t concern me. I live in the country and the end of the war will find me just as I was at the beginning of the tragedy, living in peace.’ Because it does concern you…”

“There is only one fight, and if you don’t join it, your enemy will nevertheless supply you with daily proof that that fight is yours. Take your place in it because if the fate of everyone you like and respect concerns you, then once again, rest assured, this fight does concern you. Just tell yourself we will bring to it the great strength of the oppressed, namely solidarity in suffering. That is the force that will ultimately kill the lie, and our common hope is that when that day comes, it will retain enough momentum to inspire a new truth and a new France.” (Translated by Arthur Goldhammer).

This is not writing as evasion, or redirection or submission. This is not writing as an alternative or as an amendment to action. This is writing as action. To write is to act.

When Camus wrote this, the occupation and the war were approaching their conclusions. Right now, whatever it is we’ve been going through since 2016 appears to be starting its end. Whether it happens or not, the resonance of these words and, for that matter, of Camus’ other editorials, may never dissipate as long as there are fears and loathing to be exploited by monsters.

October 10th, 2019 — movie reviews

The best thing about Joker, as far as I’m concerned, is that it makes Batman: The Killing Joke look far better in retrospect, if only because the latter animated feature from 2016 doesn’t try so hard to be anything other than a longer and more-risqué-than-usual Batman cartoon.

Given all the noise and clatter preceding and following Joker ‘s premiere, the controversy accompanying Killing Joke ‘s release three years ago sounds relatively quaint. It, too, presented a Joker origin story as first conceived by nonpareil comics writer Alan Moore in a 1988 graphic novel. As some of you may recall, the Joker was, as with the guy in the new movie, a struggling comedian. Only here, he’s got a pregnant wife and no prospects. So in desperate search for scratch, he agrees to aid and abet an attempted heist at a chemical plant only to be disfigured and, thus, deranged from falling into a huge vat of toxic glop.

Which turned out to nowhere near as interesting as what happened in the same movie to Batgirl, who ends up shot and paralyzed for life by the Joker, but not before a separate subplot during which she and Batman…Oh boy, do I want to spoil it for you! (Maybe I already have.) But some shocks to the system are most productively sustained in direct encounter.

Needless to say, fan boys and fan girls of all ages were scandalized, screeching, “How dare you heartless pigs do all this to Barbara Gordon?” They were likely remembering all the good times they had back in the nineties when the original Batman animated series was humming along as (since I have the floor and whether anybody cares to argue with me or not) the finest iteration of these characters on ANY sized screen.

There were also many critics who wondered whether the world really needed an R-rated animated action feature. But even if Killing Joke’s animation wasn’t exactly groundbreaking, the film was about as pure a noir product as any black-and-white early 1950s thriller with Lisabeth Scott and/or Glenn Ford. The storytelling was lean and measured, the dialogue was crisp and juicy and the vocal work was superb, most especially by Mark Hamill, whose rasping and cackling as the Joker over three decades of Batman cartoons showed more engagement, invention and audacity than anything he’s done as a on-screen actor.

Better than Joaquin Phoenix? Maybe…And so here we go…

Yes, Phoenix is brilliant in Joker, a bony wraith with hooded eyes and a heart so broken that its fragments seem to poke out of his spine. But it’s a lot of trouble to go to for a character we have no reason to connect with emotionally. Taxi Driver’s Travis Bickle was no better, the movie’s defenders insist. But Robert De Niro’s Travis had just enough charm at the outset to at least make Cybill Shepherd’s campaign worker agree to a date, even if that date was a fiasco. The movie gives neither Phoenix nor us any escape valve, any outlet for irony, wit or joy save for a few precious seconds when Phoenix’s Arthur Fleck joins an audience of entitled swells in laughing at Chapin’s blindfolded roller skating in Modern Times, a glimmer of footage evoking almost everything the movie either forgot or omitted.

Joker isn’t a movie so much as a giant boulder in the middle of Culture Gulch that’s too big to move or ignore. I suppose that’s why there’s been something about the Joker in every New York Times arts section over the last week and a half, at least. This morning’s paper had an article contending the Joker was a case study in thwarted white privilege. Sure. Fine. Whatever. Let’s by all means pump up the rhetoric about Joker being both metaphor and rallying cry for the dispossessed who would rather watch the world burn than engage in any rational effort to save it. The conceit lasts for as long as one forgets how yellow and frayed comic book pages can get over time and how fragile a vehicle they are, ultimately, for the most complex of societal dilemmas.

Still, there’s one aspect of Trump-ism I found in Joker that I haven’t yet found in any review or analysis, though it’s possible I may have missed it. The Gotham City depicted in the film looks most like a doppelganger for the New York City of the seventies with its graffiti-covered subway cars, its rampant street crime, its grimy, cluttered and combustible architecture. It has always struck me that at the core of so much of the president’s rhetoric and, for that matter, the Fox News Channel patter that both feeds and feeds off it is a perverse nostalgia for those Drop-Dead years of the Imperial City, when the hopes and dreams of reformers literally went up in smoke, white flight was at its peak and stigmatizing people-of-color for being the sole agents of their own desperate circumstances was used as fuel for a slow-building mad-as-hell conservative resurgence in the eighties. The Trumpeteers may not have dug the seventies — except for the way those years of squalor and decline made it so much easier for them to hate the sixties.

I realize that by bringing all this up that I’m adding to the same overestimation of Joker’s significance that I’m criticizing. My pallid excuse is that I’m only going along with the rest of the culture – and with the movie itself. I need to stop it here before it gets worse.

So I’m going to end this the way Killing Joke ends: with both Batman and Joker, mortal enemies and mirror images of each other’s obsessed, damaged souls, laughing together at the same dumb joke. It may not have the grandeur and oomph of Joker’s windup. But as with much else about that full-length Batman cartoon, it makes for a much more satisfying and logical conclusion – or do I mean punch line?

September 16th, 2019 — Politics & Other Disappointments

From Amy Davidson Sorkin in the Sept. 9, 2019 issue of The New Yorker: “…Even (Beto) O’Rourke for whom, just last year, being a senator was a dream job, said that running for the same office now ‘would not be good enough for El Paso and it would not be good enough for the country.’…On a human level, it’s understandable that O’Rourke would want to directly take on [president Donald] Trump and his bigotry; on a political level, the logic is less clear.”

You think? But in America’s present frazzled state, logic is so devalued a commodity right now that if Mister Spock made a recon field trip anywhere on this rock he’d probably mutter something like “Fuck this shit!” in Vulcan, and pivot for home. Like Beto, we’re all a little too emotional about stuff we shouldn’t and we think (when we think at all) that watching a lot of television will calm us down.

Deep breath, America: The presidency is not where you should be investing all your attention. Congress in general and the senate in particular is where crucial decisions are made, and just as often, not made that affect your kids’ lives, to say nothing of their kids’ lives.

Granted, this process has been hampered, especially in recent years, by the stubborn impediment to the national blood vessels that is the senate filibuster whose dominion over that body’s regular order of business has solidified in the public mind Congress’ position as the place where Nothing Ever Gets Done. Bring out the raspberries and guffaws, but always remember that a helluva lot of damage can be done by not doing anything. And do you need to wonder who benefits most in spreading over the collective American mind the image of representative government as being such a morass that nobody should expect anything to get done?

So that’s why POTUS gets more attention that he should. But as others wiser than me keep telling people, to little avail, the president can’t tell anybody else what to do except the military over which he is commander-in-chief. Otherwise he’s just another legislator trying to convince people to go his way; not a goddam king !!!

And I hate like hell to get vulgar about this. But if you only knew how many times during Barack Obama’s presidency that I had to keep telling younger folks, and even older folks who likely slept through high school civics classes, that the president presides, executes, but does not rule the country. “Who does?” they ask. Well…in theory, you do, I say, but that just confuses them.

So I stopped answering that question and went back to my main point: What matters as much as voting for president, and sometimes more, is voting for the right person to represent you in the federal legislature. So for that matter is voting for your state governors, mayors, city councils, school boards, and so forth. All of which, I know, sounds too boring to contemplate. I agree. Contemplation of any kind is boring. But think of all the dreams that die and the lives that are ruined because of the dearth of collective contemplation. I’m asking you to think. Again.

In fact, let’s hear from somebody who knows even better than I do what it means to be a POTUS; somebody who once commanded one of the largest armies in world history. The General has a message to Beto O’Rourke and those who are similarly inclined to battle Donald Trump next year. (Oh and maybe Donald Trump needs to hear this, too):

“Anybody is a damn fool if he actually seeks to be president. You give up four of the very best years of your life. Lord knows it’s a sacrifice. Some people think there is a lot of power and glory attached to the job. On the contrary the very workings of a democratic system see to it that the job has very little power.”

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER, 34th president of the United States

Off the top of my head, I blame Teddy White. If it weren’t for The Making of the President 1960 and White’s three quadrennial sequels, pursuing the presidency (a.k.a. the Highest Office in the Land etc. etc.) wouldn’t seem like the lumbering, furry and clunky pageant that eats up so much media space every three to four years. White’s books sold in bunches, even the 1964 installment that chronicled an election whose results were in retrospect a forgone conclusion practically from the start.

But blaming White is too easy. Better to blame the results of that 1960 campaign which is when we started on the road to wherever it is we are now. That was the year, as Norman Mailer wrote at the time, that America voted in its first matinée idol president. Granted it was by only a sliver and there were still hardheads who weren’t about to have a Catholic in the White House no matter how pretty he and his family looked on magazine covers. But the administration following that election marked the era when the president of the United States became undisputed Star of the Really Big Show that was American government. Unlike his immediate predecessor, John F. Kennedy robustly sought the presidency “because (as he put it in his last election-eve speech in Boston) it is the center of action.” This was when he was still running for the office. When he got there, it wasn’t as easy as he thought it’d be. But after the second year, he was beginning to get the hang of it enough to try reviving the old “bully pulpit” motif – one which has, alas, taken on newer, more literal meaning today.

This was the same Massachusetts U.S. senator John Kennedy who only three years before accepted a Pulitzer Prize for a book comprising portraits of U.S. senators who helped move the needle on History by going against the prevailing political climate. The title of the book was How To Put Your Ass on the Line For Little Fun and Less Profit. I kid of course. It was Kennedy’s Profiles in Courage written by Ted Sorenson (as everybody pretty much accepts now). What seems most authentic about the book, even today, is that Kennedy once believed that Congress mattered almost as much as the presidency and its members could be as consequential to the country’s direction; maybe more so as in the examples of Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, John Quincy Adams (a more effective legislator than president), John C. Calhoun, James Blaine, Thomas Hart Benton, Joe Cannon, Robert Taft and George Norris.

Soren…I mean, Kennedy even decided to include a chapter on Edmund Ross, the Kansas senator who cast the lone vote against convicting the impeached president Andrew Johnson. It apparently didn’t matter to JFK at the time that Andrew Johnson was an incorrigibly retrograde racist and that Ross’s vote may not have been as idealistically motivated towards preserving the institution of the presidency as Kennedy’s account makes it seem. It was the gesture of courage itself that was heroic enough to Kennedy to make it glow in retrospect.

You wonder when JFK stopped believing in the messianic possibilities inherent in serving as a senator or representative. Then again, he probably never really believed in them at all, having seen whatever forces, seen and unseen, that Franklin D. Roosevelt summoned against his father when the latter was ambassador to Great Britain (even though Joseph P. Kennedy Sr. did as much if not more damage to himself than Roosevelt). Indeed, we may have started measuring eras in American history by presidential administrations with FDR’s, though some might argue that process began in earnest with the eight years his cousin Theodore was in the White House. But even at the start of the 20th century, young and bombastic TR had to share center stage with congressional titans like the aforementioned “Uncle Joe” Cannon, then a speaker of the house as powerful, obstinate and impregnable as senate majority leader Mitch McConnell seems now.

McConnell, to my mind, has been a more consequential political force in this nation’s government this decade than its two very different presidents. He’s imposed his will through stonewalling, cajolery, intimidation and, to be more specific about it, transformed the U.S. Supreme Court for generations, assuming we last that long. “But he’s only a senator,” a friend I’d thought was savvier about such things told me. Right, I said. And Keith Richards is only a rhythm guitarist and Mean Joe Greene was only a defensive lineman.

I mean…Yes, it’s somewhat nauseating to put someone as malign as Mitch McConnell in the same company as Clay, Webster, Adams, Taft, Robert Lafollette, Everett Dirksen, and the Lyndon Johnson who was, as Volume Three of Robert Caro’s epic biography labeled him, “Master of the Senate.” But it took gall of previously unimaginable dimension to have blatantly, cruelly mashed and baked the dreams of Merrick Garland into soot for the sake of political expediency – and getting away with it. One also recalls the bone-chilling spectacle of McConnell staring laser-like at Susan Collins as she cast her vote for confirming Brett Kavanagh to the Supreme Court.

That, boys and girls, is Exercising Power. Whining about your predecessor’s deal with a media company is not.

So what to do? Getting rid of the filibuster has been on the table during this presidential campaign and there’s little clear consensus among the 2020 Democratic presidential hopefuls as to whether they’d support its suspension if their party regains senate control. (Elizabeth Warren’s adamantly for suspension; Michael Bennet’s against; Biden’s listed as “unclear” – huh?—and most of the others are considered “open” to the prospect, at best.) But it’s probably easier to just make sure that most of the Republican right-wingers now holding senate seats don’t come back and at least permit some legislation to pass.

But as with almost everything else that matters right now, a shift of perception is what’s needed above all else. In other words, stop thinking of our three branches of government (yes, there are three) as a pyramid where the executive branch is always on top. The best way to think of government, and I do mean “think” more than “feel,” is in lateral terms, which how I always imagined those troublesome Virginians like Madison and Jefferson saw it in theory.

This isn’t going to be easy. There was no television in 1787 and even though those Founding Fathers carry lots of star power to this day, none, except maybe Benjamin Franklin, would likely know how to act in front of a video-cam. But there once was a time in the succeeding centuries when senators were stars as big as, even bigger than the president. If we mean it when we claim to love our democracy, it wouldn’t be the worst idea to reimagine such times in our own.

April 7th, 2019 — family history, Politics & Other Disappointments

“Common sense and a sense of humor are the same thing, moving at different speeds. A sense of humor is just common sense, dancing. Those who lack humor are without judgment and should be trusted with nothing.”

— Clive James

Also true: an active sense of humor, at the giving or receiving end, is the great social leveler of American life, though you’d barely know it now as we’ve been squeezed tighter into this grim shouting match that passes for political discourse.

For me, being funny or at least “knowing” funny compensates for most political sins and I’ve gotten into plenty of trouble for making such allowances. There was much (we’ll put it at “everything”) about William F. Buckley’s politics that I found undigestible and racist, however much he walked back his segregationist sympathies towards the end of his life. Nevertheless, whenever the subject of Buckley came up among us intense student lefties back in the day, I would often get eye daggers aimed at my forehead when I dared suggest, “Well…at least he’s funny!” This is why for most of my life I could never be considered a reliable enough ideologue or revolutionary.

I blame my upbringing. (Doesn’t everybody?) I grew up in one of those households where if you couldn’t take a joke, you became one. My mother was the lone holdout. “That’s not nice!” she would say whenever the rest of us, especially my father, ganged up on something or somebody. But after a while she grudgingly accepted her role as comedic foil to the rest of us smart-assed Seymours. (Missing you, mom! In your own way, you too knew funny!) If you hung out with us for any length of time, you had to be funny or, failing that, accept your fate. Not everybody appreciated the vibe, but over the years my siblings and I came to cherish and even protect the leveling effect our collective joshing and jiving had on whatever social milieu was taken aback by our presence.

With my father, though, it was always a risk whether the one-liners would work even with my mother. And when it didn’t work with strangers, he’d just shrug and say, “I make a friend a day.”

Then again, it’s never been apparent, for all the pride we take in our stand-up clubs from sea to shining sea, that Americans can take a joke, even though they’ll all make passes at telling one.

What’s more than apparent is that the incumbent president of the United States is a dreary gasbag who can neither take a joke (thinking mostly of the bad Buster Keaton imitation he gave towards his predecessor’s jibes at a White House Correspondents Association dinner) nor tell one very well, though when he slow-dances with the flag, he’s at least convinced himself that he is funny.

My friend Colin McEnroe, who’s not only a lot funnier than President Trump but a whole lot funnier than anybody who’s after Trump’s job, conjectures that 45’s idea of funny came from repeatedly listening to Don Rickles’ 1968 LP, Hello Dummy at an impressionable age, though I would think that at 22 (assuming he’s not fibbing about his age), Prince Don T. had outgrown his need for role models. Just as generations of would-be comics thought from listening to Richard Pryor’s albums that all you needed to buy into his renown were jokes about farting and fucking, Trump likely inhaled all of Rickles’ rude noises without digesting his timing and craftiness.

Is it really so hard to be funny? To know funny? If you really want to gauge what’s been lost over the last fifty years in degrees and dimensions of political wit, compare any YouTube video of Buckley on his Firing Line talk show with ten random minutes from Fox News, his alleged ideological descendants. You may not make it past five. Tucker Carlson’s petulant browbeating veers at least forty miles wide of Buckley’s vulpine stealth. Neither Carlson nor anybody else on the Fox schedule displays anything close to Buckley’s twinkly indulgence of opposition viewpoints, during which interval either a rhetorical hammer or pointed stick loomed overhead.

Things aren’t all that giddier over on MSNBC, where one finds surfeits of enthusiasm, earnestness, passion, energy – and relatively little to make even a partisan laugh except for a sarcastic whoop here and there. I might feel a lot better being on Chris Hayes’ or Rachel Maddow’s side if every so often their respective commentaries emitted smoky-spicy ironies redolent of Fran Lebowitz.

Which, some may agree, might not be necessary. Because, as you’re already dying to tell me, we don’t need the MSNBC gang to bring the funny as long as the Jon Stewart Alumni Association – Colbert, Noah, Bee, Oliver, Cenac and company – is at work at its members’ respective platforms. I’m not disagreeing. As I’ve written elsewhere, comedians appear now to own the kind of credibility once claimed by journalists, though at least Oliver has said aloud that if it weren’t for journalism, nothing he has to say on HBO would matter. What worries me about those guys, however, is that their repeated bashings against what often seems a granite edifice of clueless cruelty could exact such a toll over time that they could become too absorbed by the chaos to be an antidote against it.

Besides which, wielding snarky comebacks in public brawls, however cathartic the blows may feel, isn’t as satisfying as the leveling process that comedy at its most bracing can yield. Though John Oliver at least will season his outbursts with dorky self-deprecation (making them somehow more effective than those of his peers), you wish for more of a kind of ecumenical acknowledgment by all sides that when you come down to it, we’re each as full of shit as the next person. This shouldn’t narrow the prospects for more and better funny. Quite the opposite.