Entries Tagged 'jazz reviews' ↓

June 12th, 2013 — jazz reviews

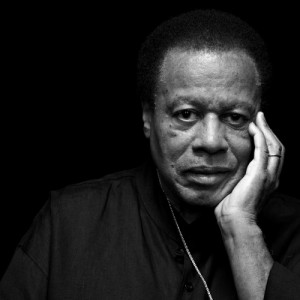

1.) During the one time I interviewed Wayne Shorter, I asked why no one had ever asked him to compose a film score. This set him off on an epic soliloquy on how male movie stars walk from Bogart, Gable and Cagney to Lancaster, McQueen and (I think) Poitier. He got up out of his chair and gave brief, impromptu imitations. He even brought Kirk Douglas into the discussion by which time he got me so caught up in whatever he was saying that I tried to bring such contemporary-cool avatars as Douglas’s son Michael and Denzel Washington into the mix (to little avail). He digressed into matters of posture, pace and the way people sway their arms in stride. It was enrapturing, frenzied and elliptical; like much of his music, only with words. I didn’t, couldn’t write any of it down because I knew I’d never get it in my paper. I wish I could find the tape, though. I also wish he’d answered my original question – and still wish that that somebody, anybody else would, too.

1.) During the one time I interviewed Wayne Shorter, I asked why no one had ever asked him to compose a film score. This set him off on an epic soliloquy on how male movie stars walk from Bogart, Gable and Cagney to Lancaster, McQueen and (I think) Poitier. He got up out of his chair and gave brief, impromptu imitations. He even brought Kirk Douglas into the discussion by which time he got me so caught up in whatever he was saying that I tried to bring such contemporary-cool avatars as Douglas’s son Michael and Denzel Washington into the mix (to little avail). He digressed into matters of posture, pace and the way people sway their arms in stride. It was enrapturing, frenzied and elliptical; like much of his music, only with words. I didn’t, couldn’t write any of it down because I knew I’d never get it in my paper. I wish I could find the tape, though. I also wish he’d answered my original question – and still wish that that somebody, anybody else would, too.

2.) In the summer of 2001, he appeared – materialized? – at New York’s JVC Jazz Festival in one of the first live appearances of the quartet that many now consider the best small combo in jazz. (This is by no means a unanimous opinion; more later about this.) So much time had passed since people heard him playing acoustic jazz with a rhythm section that there were several red-zone levels of anticipation for this show, the closing act of a three-tiered bill that, if memory served, included a crowd-pleasing Chick Corea set. The house fell in on him as soon as he walked on-stage. But the glow receded as soon as he started playing. He seemed reticent, even tentative, as if he were still hugging corners of the shadow-world in which he’d embedded himself for most of the previous decade. It wasn’t quite the rouser everyone in Avery Fisher Hall was amped for and one remembers how deflated even the most indulgent true believers looked as they filed out that night — though, to be fair, that acoustically-challenged venue may not have been the most ideal for a quartet seeking a détente between rumination and momentum.

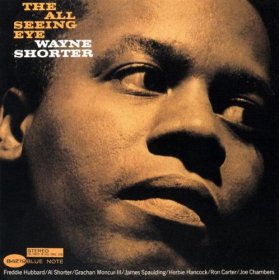

3.) On the other hand, what else DID they expect? A John Coltrane-style secular-mystical revival, radiant fire breathing and all? That’s not what you anticipate – or even desire – from Wayne Shorter, though he’s certainly proven himself capable of such incantatory drive. (I don’t know how many times I’ve played Juju among friends and found those unfamiliar with the album swear that it was Coltrane playing that tenor, even after I’ve told them otherwise.) Shorter, going all the way back to his mid-1960s tenure with Miles Davis (and more so with his Blue Note albums of that period) always connected with the writer within me. He had a distinctive, near-oblique narrative voice: lyrical, inquisitive, restless, but always with a solid harmonic foundation bracing his often-eccentric digressions. The sound of his saxophone didn’t swallow you whole as Coltrane’s could, but rather carried you along like a magical-realist storyteller. As with the best music of that era, Shorter’s playing and composing didn’t impose their mystique upon you so much as invite you to come up with your own poetic responses. George Harrison would have understood where Shorter was coming from – and for all I know, likely did.

4.) I just now remembered something else from that interview: His abiding interest in comic books and in one series in particular featuring a dauntless young aviator named “Airboy.” (There was one other hero whose name now escapes me. I’ve GOT to find that tape!) It occurred to me at that moment to ask why he never wrote a tune with “Airboy” as a title, but somehow we got caught up on another subject.

5.) As for writing a score for movies….what the hell. The way Hollywood is now, he’d be a lot better for them than they’d be to him. Best to make up your own movies in your head while listening to “Chief Crazy Horse” or “Mah-Jong” or “Schizophrenia” or “Over Shadow Hill Way” or “Calm” or “Face of the Deep” or “Deluge” or “The All-Seeing Eye” and…Know what? Even some of the titles, when you throw them in the air come across like some allusive, inscrutable and faintly volatile Shorter solo when they hit the page.

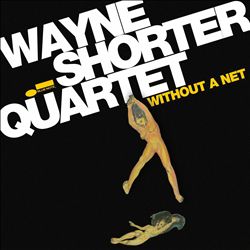

6.) So then…what about the other guys – Danilo Perez on piano, John Patitucci on bass and Brian Blade on drums? Do they and their leader deserve to be mentioned in the same breath as the Davis-Shorter-Hancock-Carter-Williams tandem – or any other classic small-jazz group that you can think of? Maybe it’s enough that Shorter always looks on-stage as if he’s overjoyed to be with them. I always had the feeling that from the start of their association, each member of the rhythm section was using his own resources to draw Shorter further out into the open. If their latest album, the aptly titled Without a Net (Blue Note) is any indication, they’re still tugging, coaxing and, especially in Blade’s case, shoving Shorter towards the deeper end of the pool. Often, it sounds as though he’s hanging back at the start, letting his fellas set the table before allowing whatever’s in his head seep or leap into view. Hence his off-the-cuff rendering of the “Lester Leaps In” theme that opens “S.S. Golden Mean,” which seems calculated to get Patitucci, Perez and Blade to ramp it up a little more. They do and this in turn gets Shorter to toss more angular shards of phrasing at unexpected times. (See what you do with this one! Wait! Think fast! I got another one.) Taking in all this freewheeling interplay is like making one’s way through a murder mystery written by a surrealist poet. There are enough familiar signposts of the genre to string you along, but the prose trips you up as often as the plot.

7.) On record, it’s engrossing; on-stage, it’s challenging, but no more so than a Bartok string quartet. (You’ll have plenty of opportunities to find out as the beginning of Shorter’s ninth decade is celebrated in live performance here and elsewhere throughout the year.) Still, many listeners coming with their own preconceived notions of what jazz is, or should be, find this quartet’s method too arbitrary and unfocused. Some might suspect the quartet’s colloquies are little more than expanded, busier editions of the airy, abstracted interplay in which Shorter and his old friend Herbie Hancock engaged with mixed results in their 1997 duet album, 1+1 (Verve).

8.) I’m nowhere near as negative, but I understand why others are. When Shorter edged his way back into full view less than twenty years ago, I hoped he’d carry with him some hooks and melodies evoking the familiar, relative solidity of “Speak No Evil” or “Adam’s Apple” – which, lest any of us forget, were considered pretty far out in their own time by those who left their hearts and heads with hard bop and cool jazz. It would seem that Shorter, whose place in history as a composer is safe and secure, now wants to find ways of inventing off the imperatives of a given moment, just as Miles Davis insisted on doing to the end. He’d just as soon share such moments with his team, the better to see where they can take him. I don’t mind the extra work they give me because as a listener, I’m taking the leap with them. True, I wouldn’t mind a net, or even a soft, wet towel at the bottom. But if “Airboy” can fly through the thickest, stickiest obstacles, Shorter believes we should at least try. You may come out the other end thinking bigger than you did before — or at least, more different.

May 30th, 2013 — jazz reviews

Dammit.

I had not only hoped, but also expected that Mulgrew Miller would have one of those lives and careers that endured for decades longer than he was allotted. He seemed destined to become one of those gray eminences of the jazz keyboard who would be around for another generation or two as a living exemplar of jazz piano’s essential verities very much in the manner of Hank Jones, Tommy Flanagan, John Hicks, Kenny Barron and Barry Harris. He’d found a niche at William Paterson University as director of jazz studies in which role he formally – and from the evidence here, effectively – carried out what he’d been doing informally since his 20s: influencing and mentoring younger musicians eager to follow his example.

As others have been pointing out since yesterday and will likely continue to do so over the next several days, Mulgrew Miller played with a faultless blend of grace, lyricism, clarity and unassuming resourcefulness that threaten to attract the label of “jazz pianist’s jazz pianist.” While this is intended as a compliment (and there are far worse things people can say about you), it also feels reductive, inexact and inefficient – especially when one gazes at the vast and expanding field of jazz pianists who have legitimate claim to that title. Each of us, in whatever trade or calling we pursue, is the sum of our accumulated influences and experiences; it’s what we do with that internal file that matters. When I listen to Miller play, I hear a generosity of spirit, inventive enough to keep your attention, yet deeply grounded in the rhythmic and harmonic foundations of what, for want of a better term, is considered “post-bop” jazz. You don’t always have to bend or twist tradition out of shape in order to get a rise out your listeners. You can endow the familiar with such authority, power and dynamism that it achieves a kind of eloquence that lingers in the imagination. As a leader and as a sideman, Miller hit those points so frequently that he created his own posse of devotees who followed him from an evening’s session at the late, lamented Bradley’s in the Village to whatever album was lucky enough to have him in the roster.

I’m lucky, in any event, to still have some of the now out-of-print discs he recorded in the early-to-mid-1990s for Orrin Keepnews’ Landmark label and on Steve Backer’s Novus series. (My favorite from the former: 1992’s Time and Again; from the latter, 1995’s With Our Own Eyes. They’re both worth hunting for in used-music bins, on- or off-line.) He also assembled quite a catalog as a leader on the MaxJazz label, especially the two-disc Live at Yoshi’s trio sessions. He always seemed so prolific and busy that you took it for granted that his protean work ethic would receive even greater rewards further down the road with the kind of wider recognition that reached Flanagan, Jones and others in their golden years. But he – and we – have been cheated out of that prospect. Dammit. Again.

May 3rd, 2013 — jazz reviews

The best jazz recording of 2012, much like science or magic, doesn’t easily yield its secrets – which is the main reason it didn’t make my Top-10 list. I simply didn’t get to it all in time. Still, with or without me (and gratifyingly so), Wadada Leo Smith’s Ten Freedom Summers has by now received most of the formal acclamation it deserves: Finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in music, awards from the Jazz Journalists Association for Smith as musician and trumpeter of the year, a three-night live premiere last week at the Roulette in Brooklyn. I suspect that once the four-disc set on Cuneiform Records seeps into the shared consciousness of receptive listeners, it will continue to provoke, haunt and inspire. The greatest music – the greatest anything – doesn’t end when you stop absorbing it. Your reactions, primary and secondary, are part of the artistic process. They’re supposed to be, anyway.

Each of the nineteen compositions in Smith’s five-plus-hour opus announces itself as a chapter in American history from the 1857 Dred Scott case to the 9/11 terrorist attacks. But the thematic core of Ten Freedom Summers, as its title suggests, is the decade of national transformation that began with the 1954 Supreme Court decision declaring school segregation unconstitutional and the 1964 summer that saw both Congress’s passage of the most sweeping civil-rights legislation since Reconstruction and the Mississippi “Freedom Summer” Project during which activists risked (and lost) their lives trying to enfranchise the state’s besieged African-Americans. With Smith on trumpet leading both his Golden Quartet/Quintet of pianist Anthony Davis, bassist John Lindberg, percussionists Pheeroan ak-Laff and Susie Ibarra and the nine-member Southwest Chamber Music Ensemble conducted by Jeff von der Schmidt, the work spools forth as a meticulous inventory of mood more than a sweeping pageant of struggle. It doesn’t chronicle its noteworthy events so much as search for their deeper emotional currents and, in doing so, compels the listener to react to history beyond text and shadow – and even further beyond the blithely-dispensed shorthand of newsreels, archival photos and sound bites.

I wonder, though, whether I’m probing or merely projecting whenever I hear some of its chapters. Just to take one example, the piece entitled, “Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott, 381 Days.” It begins with a major-key dirge by Smith’s trumpet, with a tone and tempo reminiscent of such mid-1960s elegiac milestones as Lee Morgan’s “Search for the New Land” and John Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme.” One can easily interpret this table-setting incantation as signaling the no-turning-back-now gesture by Parks in her epoch-making refusal to sit in the back of an Alabama public transport. Then, for several bars afterward, a chugging 4/4 beat, driven by ak-Laff with bouncy strides, conveys the “381 Days” of the resultant boycott, which forced hundreds of domestics, office workers and laborers to walk instead of ride to work and shop, thus representing the first of the era’s significant civil-rights marches.

I’m confident I’ve sussed that out correctly. But when I hear the strains of bluesy strutting at either end of “Thurgood Marshall and Brown Vs. Board of Education: A Dream of Equal Education,” am I being cued to imagine the swagger and bravado of its eponymous heroic lawyer making his way through several litigious hurdles to reach his finish line at the Highest Court in the Land? And would I know enough to respond to such cues if I didn’t know what its title was? Or, for that matter, know who Thurgood Marshall was and the kind of ribald, larger-than-life figure he was?

It helps to know the history behind the music. But it’s not necessary. Because even if you can sense why Smith and his musicians make the choices in what they play and how they extend their ideas (together or separately), it’s the spacious-skies expansiveness of the concept itself, its willingness to do the unexpected – a segment on the “Black Church” that’s all swirling chamber music and no gospel tropes whatsoever – and let you deal with its implications, that allow you to sense that “freedom” is far more than the theme of Smith’s work here. It’s both his method and his objective.

Smith, after all, was forged in the crucible of what, for want of a better description, we still label “avant-garde jazz.” And what would be a better description? There are so many options. Some like “progressive jazz,” though you kind of feel an anachronistic draft when you hear those words. Others cling to such sixties taglines as “New Thing,” “Fourth Stream,” “Outside” and even “Free Jazz,” though some of the renegades of subsequent decades embraced old-school polyphony that kept things flying in fairly close order. Gary Giddins quixotically tried to coin the word, “parajazz” (or was it “Para-Jazz”?) as an all-purpose umbrella. I like it, but I can’t find anybody else who does.

I also like “creative music” — bringing us back to Smith, who was part of the groundbreaking Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) that nurtured and/or inspired such experimentalists as Henry Threadgill, Anthony Braxton, Roscoe Mitchell, Joseph Jarman, George Lewis, Leroy Jenkins and many more. Their music was as idiosyncratic, original and unconventional as they were. Jazz fans who drew their lines at whatever Miles Davis was doing in 1965 (if not sooner) thought the AACM and their kind were too “way out” to even taste. But back in the seventies, I warmed to the freewheeling, sometimes breakneck invention of the renegades. It’s true they made mosaics out of traditional rhythmic pattern and carried thematic ideas down dark alleys and wooded glades you never thought of visiting. But as with avant-gardists of the past, they weren’t upending the order-out-of-chaos imperative of art as much as encouraging listeners to re-fashion or, at least, reconsider their own notions of order. In other words, they weren’t the only ones creating the music; you had to join in the process, too. And where previous generations did so by dancing, we did it by thinking or feeling our way through the changes.

Smith, now 71, has for decades advanced his own vision of creativity into finding new ways of fusing improvisation and notation. (He explains this process in far greater detail here, though, as with his music, one run-through won’t be enough.) Ten Freedom Summers uses the late 20th century’s upheaval to apply firmer context to the process. Those unaccustomed to such compulsively creative composition may think it’s haphazard, even if they know the historical facts being represented or dramatized. But as it was with the avant-garde’s loft concerts of the 1970s or for that matter, some of the late, lamented Knitting Factory’s wilder nights of the 1990s, the whole idea was to listen and to be attentive always for whatever is familiar in one’s own memory, private or public, and for what could be something you never knew before. From such surprises, you can make your own connections to this freedom struggle – or any other such struggle you can imagine. It may well have been this openness to possibility that the Pulitzer committee recognized in almost-but-not-quite giving their top prize to Ten Freedom Summers. If so, then it’s a whole way of thinking about music, and not just jazz, that’s received its just desserts.

March 22nd, 2013 — jazz reviews

A big shout out to those of you who responded to the previous post on Thomas Chapin’s newest CD set, Never Let Me Go. Lots of love out there for Tom, who deserves all that & more. Among the many who responded: Stephanie J. Castillo, who is trying to pull together enough funds for a full-length documentary about Tom. Here is the site — with all the information on the Kickstarter campaign & every important link related to Tom Chapin’s life & legacy.

Whatever you can do, patrons. The Home Office will be grateful. The campaign has roughly a week to go & they’re still not near the goal of $50,000. So she’s asking people to take part in the “100 X $100 Group Give.” Do the math. If 100 people give $100 over the next five days, $10,000 from the Group Give will help meet the $50,000. Of course, all amounts – small and large — will be accepted.

The previous post said mostly everything I needed to say about Tom…except, maybe….

OK, bear with me. In February, 2008, a memorial concert for Tom was staged at the Bowery Poetry Club. There was more than enough words & music to share that night. But I felt somewhat bereft, being only a spectator & knowing Tom as I did. It wasn’t until a couple days afterwards that the following fantasia rolled out of me. I wish it had rolled out that evening, but I guess it wasn’t ready.

So with your kind indulgence, here’s that side-dish of speculation mentioned on the marquee, a meeting that never happened, but should have. It’s a little wig-bubble The Home Office is labeling:

WHEN MILES MET TOM or THE FINAL FRONT LINE

It’s September of 1991 and a gravely ill Miles Davis is, as Lord Buckley would put it, not merely “on the razor’s edge”, but on the “hone of the scone,” whatever that is, if that is what it is.

Anyway, Miles is in his Malibu manse, semi-conscious, hooked up to all manner of wires and tubes. Deep down, he knows that this is all pointless. It definitely feels like Checkout Time’s arriving at any minute and all he can do is drift in and out of reality, trying to take in as much as he can before the lights go completely dark.

He can dimly hear a radio piping in music from another room. Some dumbass has it tuned to a jazz station. Fuck that, Miles thinks. Anything but that! And it’s not just plain old jazz, but that squealing and squawking shit that Trane helped spread like a virus. I do not need that shit taking me out. I’ll take Manto-fuckin-vani over this!

Just like that, his espresso eyes, which were starting to cloud over mere seconds ago, sharpen into hard, clear points as he hears this gorgeous, passionate alto sax solo soaring and slicing its way through the miasma. He’d love to sit up so he can hear better and, to his astonishment, he almost feels as though he could. The keening, probing sound continues to jab its way into his consciousness. He digs the raw aggression, the rippling arpeggios and, more than anything else, a tone that sounds the way light would sound if light could make sound. Mothafucka can play his ass off!!

At that moment, a male nurse walks by his bed. Miles emits soft murmurs, which is the best he can do. The nurse doesn’t hear anything. Drastic measures are called for, so Miles attempts to simulate some sort of spasm. It’s lame, but it works. The nurse walks over.

“Miles?,” the nurse whispers.

“Hmmrefffrrr,” Miles says.

“I’m sorry. Do you need anything?”

The music’s almost over. If only someone would take these tubes out of his goddam nose…

“Mwhegfffrrgggrdr.”

“Mister Davis,” the nurse leans close to the parched, scarred lips. “I still can’t…”

A raspy bullet, whatever’s left deep inside him, is violently pumped through his ravaged larynx into the idiot’s ear

“I SAID, who’s that on the mothafuckin radio, goddammit!”

After a series of confusing exchanges, someone else in the house, presumably whoever had the radio on, finally figures out what Miles wants to know. He tells him that there was this bootleg tape of a young reed player out of New York, used to play with Lionel Hampton, but he’s just starting to make a name for himself in the downtown scene. Album’s not even out yet…

Miles can sense the steam rising within him. It feels good, almost human, but he still sounds exasperated and weak at the same time. “Who…is…that…motha…fucka?” Serious coughing, maybe a trickle of blood…

The name, the fool says, is Chapin. Was that his first or last name? Oh, right. Yeah, Tom. Thomas Chapin…

Orders are rasped. Call that station! Get a copy of that tape! Find out where that mothafucka lives! Now, goddamit! And so on…

Sooner than it’s possible to imagine, given the circumstances, Miles is on a long-distance call with Tom, who thinks at first that someone’s fucking with him. When he realizes, it’s not a joke, he thinks: Oh, my God! I’m on the phone with Miles Davis! And he sounds TERRIBLE…

“Lissen, man,” Miles says weakly, gasping for air, “how soon can you get your ass out here? With…that…sax…”

“Um,” Chapin says, not sure he heard correctly, but he answers anyway. “I dunno, Mister Davis, when do you…”

“Now! Yesterday! Last week, goddammit! I’m dyin’ out here, man! I want…(wheeze)…I want to record with you…Just for one time…”

Chapin is now certain someone’s messing with his head, big-time. He observes, tentatively, delicately that Miles may not…make it…by the time he flies to L.A. even if he leaves that second…

“Well, then you better hurry your ass up” Click.

From here, it’s too quick and hazy to keep track, but Thomas Chapin has somehow made the next flight from JFK to LAX. Miles, or someone close to him, takes care of traveling expenses and studio time.

Time movies fast. Here’s the studio, but where am I, Chapin wonders. Is it dawn or dusk? Where did this rhythm section come from and how many of them are there?

Miles is wheeled into the room, connected to a respirator. There’s no way, Chapin thinks. But the horn is in Miles lap, poised for action. Miles, forgoing amenities, croaks out the only three words he will say to Tom Chapin all day:

“Follow…my…lead.”

What follows is the kind of music that wills itself forward without stopping for thought or breath. It free-associates itself into something that’s neither funk nor free, neither “inside” nor “outside”, neither modern nor post-modern, neither swing nor rock; more to the point, it’s none of these things exclusively but a dense, yet buoyant amalgam of mid-to-late-20th century music’s varied precincts, high, low and in-between. It is, in other words, music that only Miles Davis could have set in motion – and that only Thomas Chapin’s luminous tone and inquisitive chops could help him finish.

Ten hours and six tracks later, the last testament of Miles Dewey Davis is in the can. He returns to Malibu to await the final call, which comes as Tom is in mid-air somewhere over western Pennsylvania on his way back to the city…

The session? Well, you know what happened with that session. By now, everybody knows what happened with that session and how it helped make jazz’s next century a …But that’s another fantasy, isn’t it?

March 20th, 2013 — jazz reviews

The first time I heard him play was sometime in 1988 on an LP (ask your parents, kids, because I hear they may be coming back) entitled, The Sex Queen of the Berlin Turnpike, a jazz-and-poetry mix written and produced by a central Connecticut crony of mine named Vernon Frazer, novelist, raconteur, boxing aficionado and bass player who’d provided musical accompaniment to his readings here and, in years to come, at such venues as the Nuyorican Café and the Knitting Factory.

As I listened, I became acutely aware of this flute coiling around Vern’s incantations and bass lines in lucid, deceptively simple patterns. As I grew up a flautist manqué, however reluctantly, I paid attention when people did unexpected things with the instrument, especially in jazz. And whoever was playing had nailed down a lyrical, probing style that refused to lean heavily on the flute’s naturally pretty tone. (The tone wasn’t pretty. It was beautiful, rich and – was it possible? – evenly layered.) And then I heard the alto sax solos. They could burn like scalding water. But they also soared; sometimes like jets, other times like gliders. More than anything, it was the relentless invention, the let’s-try-anything ingenuity that knew how to swing, bop and blow the blues in the grandest manner, but could step “outside” conventional changes with a nonchalance that seemed highly evolved even for the greyest of beards.

I checked the name on the cover: Thomas Chapin. Hadn’t heard of him before that point and was chagrined at myself for not paying attention. I’d assumed he was this lesser-known veteran of the black music wars who likely spent the previous decade-and-a-half trolling through lofts along the eastern seaboard. “Who is this Thomas Chapin cat?” I wrote Vern, who in turn told me he was this barely-thirty-something white guy from Manchester, Connecticut.

Manchester? Really? I’d spent part of my early newspaper years writing about that east-of-the-river suburb and, whatever its myriad virtues and defects, the next-to-last thing I’d have expected was someone who could wail like this. When I played this record to another colleague from those long-ago Hartford Courant days, his head swiveled as sharply as mine had to the sound of Chapin’s alto. When I told him who was playing and where he was from, my friend shook his head. “Shit, man,” he said. “Nobody from Manchester ever blew like that!”

It’s been fifteen years since Thomas Chapin died at just 40 years old and I still find myself wondering what he’s been up to. I keep thinking he’s got to be on some club’s weekend schedule, leading a trio or quartet in support of a new disc or performing yet another homage to his idol Rahsaan Roland Kirk. No matter where Tom would be, he would be turning heads, winning friends, encouraging people to come over to his side, no matter how forbidding or unconventional the setting. That’s what he always did, on- or off-stage. That’s why we miss him.

He was a member in good standing of the crowd of cutting-edge dynamos who waved the progressive-jazz banner throughout the eighties and nineties in downtown New York (a scene whose central HQ was that aforementioned Knitting Factory). Yet he also turned heads among more-traditional-minded listeners as a distinctive and highly accomplished post-bop player with a bright, lightly jagged tone and a prodigious, often-stunning range of expression. As with generations of musicians who had apprenticed under Lionel Hampton (in whose big band he’d worked for five years), Chapin carried “Gates’s” lessons of brash showmanship in his own trick-bag. But he never pandered to or shortchanged expectations, whether swinging from the core of a hard-bop standard or generating torrents of chromatic density off a simple riff.

The straight-ahead side blooms like fireworks on Never Let Me Go (Playscape), a recently-released triple-CD of Chapin leading quartets at two New York venues. The first two discs are from a November, 1995 show at Flushing Town Hall with pianist Peter Madsen, bassist Kiyoto Fujiwara and drummer Reggie Nicholson. The third disc teams Chapin and Madsen with the bass-drum tandem of Scott Colley and Matt Wilson at the Knitting Factory on December 19, 1996 – Chapin’s last live date in New York City. (He’d been diagnosed with leukemia the following year.) Though Chapin’s last studio recording, 1997’s Sky Piece, remains the one true gateway to his life’s work, Never Let Me Go evokes the warmth of Tom’s personality and the exhilaration he could communicate even to those who may not have fully appreciated his chosen idiom.

Ecstasy leaps from the first track, “I’ve Got Your Number,” whose chord changes provide a gauntlet for Chapin’s breakaway speed and power. There was never anything tentative about his attack; not even when, on the silky “Moon Ray,” the tempo gears down to stealth mode and Tom summarily shifts to shrewder thematic tactics. Along with his many other gifts, Chapin easily complied with Lester Young’s directive to “sing a song” when he played – which meant, as Prez suggested by example, to find the songs within the song that needed to come out. More than most of his downtown confreres, Chapin always exercised this prerogative, even on songs that weren’t part of the classic-pop canon as exhibited here on both “You Don’t Know Me” and “Wichita Lineman,” whose melodies Chapin irradiates with such conviction that you get the feeling he could have, in time, single-handedly embedded them both in the traditionalist fake-book.

His own compositions become occasions for Chapin’s more imaginative dramas of harmony and rhythm doing their approach-avoidance ritual. These are most prominent on the Knitting Factory gig; it must be noted that Matt Wilson, whose own embraceable style and personality are mirror images of Chapin’s, opens wider terrain for both Madsen and Chapin to lunge at the edges of time and space. On such pieces as “Big Maybe” and “Flip Side,” whatever ambiguities, discordances and incongruities play their way through each solo do so from a solid core, which Wilson tends with inviolate calm, but also with a gentle persistence of vision. Madsen makes his presence even more pronounced on the latter set; he builds his own model airplanes to fly as eccentrically, yet as emphatically as Chapin’s own. Together, this group could have helped make the cutting-edge a place where all would be welcome, exalted and, eventually, transformed. It’s nice to think so anyway.

When someone dies as prematurely as Chapin, there usually come in his wake several voices inspired by his example to fill the void. (Think of all those bright, hot horns who picked up where Clifford Brown left off. Or all those actors who are still filling in the blanks left behind by James Dean’s car crash.) In the decade-and-a-half since Chapin’s death, those examples are harder to find, especially his ability, or more accurately, his impulse, to bridge the gap between progressive and traditional jazz music – or to, at the very least, extend what critic Jim Macnie characterized as the “dialogue” between two wary, warring factions. As jazz kept shifting shape at the close of the century, bending and twisting itself into new forms while struggling with how much of its past forms it should retain (or shed), Thomas Chapin offered a model for the music’s future by making his own art pliant, inquisitive and open enough to accept whatever the times demanded. I don’t know whether the “amalgam of freedom and discipline” described in Chapin’s Allmusic.com biography could have slowed down or even stopped jazz’s free-fall in a music marketplace that became even more mercurial after his death. But I’m far from alone in wishing he’d had more time to try.

January 2nd, 2013 — family history, jazz reviews

For our site’s inaugural posting of 2013, I proudly & happily yield the floor to Chafin Seymour (BFA, Dance, The Ohio State University, 2012), who has picked up his father’s end-of-the-year compulsion to assess the things he hears and let the world in on what he thinks of them. Unlike his father, he does his list, you will note, in ascending, rather than descending, order (“Opa Letterman Style!” And, no, you wont find no damn Psy on this list.) He also shows righteous critical acumen that, were I an overly envious person, would make my teeth ache. Instead, “my heart soars like a hawk”! (Name the movie. Win no prizes.) It would seem I have helped re-birth Lester Bangs, though he dances a whole lot better and takes better care of himself…I hope.

These are my top albums of 2012. I will not go overboard with my intro except to say that 2012 was an exceptionally strong and eclectic year in independent and pop music, and I had a hell of a time deciding what I wanted to write about for this year end wrap-up. I decided on these fourteen albums (four honorable mentions and a top ten) arduously and carefully.

Honorable Mention

Killer Mike – R.A.P. Music

Cagey rap veteran Killer Mike finally does his name and reputation justice. Independent, political, and fiercely opinionated, Mike makes the album we have been waiting for, with help from Brooklyn producer El-P, who takes some of the usual distortion out of beats in favor of banging southern bass. It is a smart choice that allows Mike to rock in his comfort zone from start to finish.

TNGHT – TNGHT EP

THE party record of the year, hands down. This five song EP from producers Lunice and Hudson Mohawke was a giant smack across the face of modern dance music. Combining “trap” style southern hip-hop bass with elements of House and Dubstep (note the intense-ass-drops on every track), TNGHT reveled in simplicity and space while urging pop consumers and club kids to “wake the f’ up” and notice some real “ish.”

How To Dress Well – Total Loss

This was the first proper cohesive album from How To Dress Well’s Torn Krell. He continues to play with traditional R&B arrangements by taking out all the warm and fuzzy stuff to leave you with an anxious, empty sound. He does let some color in on tracks like “& It was U” but overall stays distant. Never has a bad break-up (and crippling depression) sounded so smooth.

Burial – Kindred EP & Truant/Rough Sleeper

I have always described Burial as being on “another level” from other electronic producers and the two EPs released by William Bevan this year continue to prove me right. While eleven-minute electronic house opuses steeped in otherworldly distortion and dark ambiance may not be the most palatable thing in the world, it is good to see an artist unafraid to explore the world he chooses to create. While we wait for another jaw dropping album like 2007’s Untrue these two excellent EPS will just have to be enough.

Top 10

10. Four Tet – Pink

As any one who has spent a lot of time around me in the past year can tell you, I have been really into house music. In fact, much of this fascination was instigated by Four Tet’s fabulous Fabriclive mix from earlier this year. Many of the tracks off of Pink were released as singles or EPs, but they were really begging to be compiled. Four Tet (actual name, Kieran Hebden) is an electronic music veteran. He has put out six very different albums and more live mixes and song remixes than I care to imagine. Pink finds Hebden diving head first into the club. Where earlier records were rhythmically restrained in their minimalist tendencies, Pink lets the rhythm drive and builds the structure around those. Loops abound and bass pounds, but you never get the sense that Heben is leading you on aimlessly. This is music based in his roots, and you can tell he cares. This is really a great introduction to house music for someone with little to no experience, and rarely does a modern producer delve so deeply with no effort showing. Never has so much thought gone into music that encourages folks to stop thinking and just let go. You will dance my friends, oh yes, but you will do so consciously.

9. Alabama Shakes – Boys & Girls

I was a little skeptical of Alabama Shakes before I listened to them somewhere between the NPR accolades and adult-contemporary following. However, I allowed myself to indulge in this album. It is four-piece, grungy southern blues-rock in its purest form, nothing overly deep or onerous, and that is key. What really reaches through the speaker and grabs you is lead singer Brittany Howard’s primal howl. From the thumping “Hold On” to the trickling “Goin to the Party” to the love ballad of the year “You Ain’t Alone,” the consistency, believability, and sense of desperation of her vocals make up this album’s driving force. While there were other notable blues-rock releases this year, namely Jack White’s strong solo album Blunderbuss, nothing stuck in my mind so concretely as Boys & Girls. In this case, less is most definitely more.

8. Jessie Ware – Devotion

In a post-Adele world how does a young, female, British singer-songwriter make her work stand out? There probably isn’t one right answer to that question. But Jessie Ware certainly offers an intensely-appealing album of suggestions. Ms. Ware made her start singing hooks on electronic dance songs by the likes of SBTRKT and much of that club influence spills over into Devotion, her first solo work. However, despite the “of-the-moment” nature of the production Ware manages to expertly write and sing timeless love songs. The centerpiece ballad “Wildest Moments” is a song that could have gallivanted into glory by expressing the joys of a one-night stand or healthy sexual relationship. Instead, Ware manages to add uncertainty and poignancy by singing about a relationship that only makes sense to the two people involved. This attention and care makes an album that could easily have been just another pop-diva’s introduction into a collection of smart artistic choices and memorably intimate melodies.

7. Grizzly Bear – Shields

I’ll be up front: I love Grizzly Bear, always have. Ever since I heard those first tenuous notes of 2006’s Yellow House followed by the complete work-of-art that is 2008’s Veckatimest, Grizzly Bear has managed to run the emotional gauntlet from warm intimacy to cold distance. Shields finds the Brooklyn band venturing out into the wilderness to look beyond their own backyard for influence. Musical references range from jazz to The Beatles; somehow they manage do it all justice. The arrangements on this album conjure up landscapes as breathtaking as they are intimidating. You can feel that Shields came to be, relatively seamlessly and naturally when compared to the endlessly worked-over quality of earlier albums. In interviews, Grizzly Bear has said that this album was the most collaborative in terms of songwriting, and you can feel the vibe of a band intensely comfortable working together. In lesser hands, songs like these could easily be sappy or overly buttoned-up; in this case, it’s just What They Do. I’ll be damned if I can think of a band that does it better.

6. Beach House – Bloom

The most glaring critique I keep hearing about Beach House’s Bloom is that it “sounds too much like their earlier stuff.” While this is true, that fact is also precisely what makes Bloom such a strong effort. It has taken three other albums, but Victoria Legrand and Alex Scally finally take their synth-and-guitar-driven-dream-pop out of the bedroom and into the big wide world. The depth and scope of this album is impressive, as every song seems to, indeed, “bloom” from start to finish. Legrand’s voice is as scintillating as ever and the arrangements are indeed lush. However, her newfound lyrical assertions as well as the use of more confident percussion and rhythmic structures deepen and widen a sound that could easily peg a less-adept band into a corner. Beach House knows where their niche is and, instead of shying away from that, they have found a way to dive deeper into it. Bloom seems to say, in response to the criticism mentioned earlier, “Yeah it does and try to tell me you don’t love it anyway.” I can’t, and neither should you.

5. Grimes – Visions

Grimes is definitely a product of our over-digitized culture. Canadian art-student Claire Boucher makes music entirely on her laptop using technology that is, relatively speaking, available to anyone. She has garnered a following and buzz using just the Internet, no record label needed, and Visions is Boucher’s most accessible release to date. Despite being an indie darling (thank you Pitchfork), Boucher does something unexpected here by making something she clearly enjoys as opposed to trying to please critics or an audience (a tactic, I believe, more artists, in and out of music, should look into). You can tell she is having a lot of fun with this record. Her layering of her own sugar sweet vocals over gloppy, bounding digital tracks is equally appealing and subversive. The fact that you can hardly understand her lyrics (I’m pretty sure she slips into singing in Japanese on a couple tracks) is part of the escapist absurdity of it all. Visions is not the easiest album to listen to, to be fair. But it truly grows on you, going from ridiculous to danceable to contemplative in just a few minutes, further reflecting the over-stimulating effects of the Internet. By allowing yourself to revel in the commentary as well as the fun, Visions becomes a worthy indie-pop experience.

4. Kendrick Lamar – good kid, m.A.A.d city

good kid, m.A.A.d. city has already been hailed by some critics as, “the most important commercial rap album in the last decade.” So let’s calm down and start by jumping off the Kendrick Lamar bandwagon for a second. Yes, he is a skilled lyricist with a strong instinct for radio-friendly hooks. Yes, he expertly chooses assorted beats from the best of today’s hip-hop producers. Yes he’s been featured on every hot hip-hop track over the past six months. Yes, he can count such industry heavyweights as Lady Gaga and Dr. Dre in his corner. However, despite the buzz, what stands out most about Kendrick Lamar is his ambition. This album is subtitled a “Short Film” and indeed the scope of the narrative-driven LP can feel a bit cinematic at times. It contains twinges of naïveté, with stories of adolescent peer-pressure and family alcoholism (“Swimming Pools (Drank)”), mixed with youthful bravado (“Backseat Freestyle”), and a dash of timeless swagger (“Bitch, Don’t Kill My Vibe”). At the edge of it all gnaws the darkness and emptiness of growing up in South Central L.A. gang culture (or, for that matter, any violent American urban center) and the cultural contradictions often present in African-American culture, such as devotion to God and religion equal to that of substance abuse and violence. It remains to be seen where this album will fall historically; hence my tentative urging to give it some breathing room. It is, nevertheless, instantly recognizable as an important and original portrait of urban music in 2012 — and, by far, the strongest rap offering I have heard from a new artist in quite some time.

3. Frank Ocean – channel ORANGE

There is little doubt in my mind that Frank Ocean is the future of urban and pop-music. I am also decidedly OK with that. After an early mixtape in 2011, the phenomenal Nostalgia, ultra, and tabloid fodder regarding his sexuality, Ocean, whose birth name is Christopher Breaux, emerged from the hype with the meticulously-crafted channel Orange. The album is meant to transcend boundaries and identities, and it does. At first listen, it can come off as simply a strong debut from a pop singer. You can feel how much Ocean has sharpened his teeth while ghostwriting for such artists as Justin Bieber and John Legend. However, upon repeat listening, one can begin to recognize channel Orange as a much stronger statement; not just on Ocean’s pop sensibility but on America’s. The fact that a song as cloyingly sweet as “Thinkin’ Bout You” can slide into play on urban radio stations next to Rick Ross and Meek Mills, while still being a sing-along favorite for soccer moms, is both impressive and intelligent. This eclectic, constantly-shifting mix of pop ideas is so deftly, almost nonchalantly, executed that by the time you realize you’re listening to a John Mayer guitar solo over gloomy, ambient synths at the end of “Pyramids,” it’s almost too late. From start to finish, Frank Ocean plays to our comfort zone while periodically throwing in ideas you would not expect. A delight to listen to as well as to discern, channel Orange is an unexpected pop pleasure.

2. Flying Lotus – Until the Quiet Comes

This album represents a musical and intellectual quandary to many people. A traditionally hip-hop/electronic producer strips down his digital cacophony with (get this) live musicians. Steve Ellison (a.k.a. Flying Lotus) has embraced his heritage. He is the great nephew of Alice and John Coltrane. After releasing three albums to increasing critical acclaim he arrives with the wonderfully-understated Until the Quiet Comes. It is, in essence, an electronic jazz album. But before you write it off as overly experimental, just put it on and let it take you for a ride. The way in which Ellison can synthesize so many disparate elements (African percussion, free jazz, West Coast hip-hop etc.) into a cohesive sonic journey is a wonder to behold. The influence of fellow Brainfeeder Collective member, Thundercat is clearly discernable in the strong bass lines and psychedelic milieu. The use of live set musicians, as opposed to exclusively digital instrumentation, further expands Ellison’s current trajectory. Nothing here seems forced. And despite existing in a clear and heady intellectual space, there is something discernibly intimate and personal about this album. You really feel as though Ellison has found his “quiet” place where all his musical ideas can flow organically and take shape on their own.

1. Dirty Projectors – Swing Lo Magellan

For those of us keeping score at home Swing Lo Magellan represents Dave Longstreth’s eighth album in the past decade with his Dirty Projectors project. What is most impressive about the latest effort is the seeming lack of it. Longstreth finally seems comfortable in his own skin as a songwriter. Not to say he has abandoned his distinctly complex vocal harmonies or tempo shifts, but he has found a way to not let his technical arrangements get in the way of simple and pleasurable song writing. Swing Lo Magellan is a collection of literate love songs for a generation of young people hyper aware of the impending doom of society. However even in the darker moments of the album (such as “Offspring are Blank”), Longstreth trusts in his expressive and eclectic musicality to carry through while allowing himself to be lyrically playful. This is by far Dirty Projectors most accessible and fun release to date and it is undeniably catchy. Try getting the chorus from “About to Die” or “Impregnable Question” out your head after one listen…Impossible.

November 27th, 2012 — jazz reviews

So I’m finally catching up with Homeland after months of people yelling in my face about how my not being able to pay for Showtime was keeping me from a television series whose significance to our time-and-place rivals those of The Wire or The Sopranos. Even with all this hype and glory leading the way, nothing I’d read or heard before I dove into the DVDs alerted me to the relatively-minor-but-to-me-significant fact that Carrie Mathison, the ruthless, bipolar CIA counterterrorism operative played by Claire Danes, is a serious jazz buff.

At first, I’m thinking: How great for jazz to have even this much ancillary presence in a prestigious pop-culture phenomenon. And then I think, well, yeah, but…she’s, like, clinical, man! And not always in a good way. Do the producers imply that jazz is part of her problem, or a plausible way out of her personal wilderness? Hard to tell so far, except maybe for a crucial clue she derives early in the first season from watching a bass player’s fingers work through a chord progression. These days, serious jazz buffs, with or without their maladies showing, will take whatever they can get in validation from the zeitgeist.

Somehow, jazz goes on, with or without pop validation – even, as one keeps hearing, without compact discs, though one also hears of something called “vinyl” making inroads in the marketplace. One is still haunted by the passage of time – and of those who helped write the history of jazz’s first century. One of my picks is led by a man who died in 2011, and most of the albums listed here pay homage to another, bassist Paul Motian, paragon and patron saint of progressive music, who mentored or inspired many of the musicians cited below Nevertheless, those who follow Motian’s example aren’t standing still, but moving ahead, heedless of what the aforementioned marketplace is thinking about – when, that is, it bothers to think at all.

1.) Ron Miles, Quiver (Enja/yellowbird) – This intricately-wired gadget had me at hello with “Bruise” – which, at least to these ears, compresses the wavering emotional trajectory of one’s average 24-hour existence into nine-and-a-half action-packed minutes. And, as with any album worth its ranking, it just gets better from there. You wouldn’t think you’d get a big, thick sound out of a trio comprising a trumpet (Miles), a guitar (Bill Frisell) and a trap set (Brian Blade). But this isn’t your average chamber-jazz aggregation. It’s a pocket-sized orchestra with Frisell in top form, whether laying down chords broad enough to encircle a botanic garden or spinning contrapuntal phrases that make antsy-little-bird patterns in the sky. Blade’s already established himself as the most audacious of his generation of drummers and he proves here that his ears are as big as his moxie. Miles, one of the versatile and underappreciated horn players of the present day, leads the way with a nerviness too assured to put on airs, but not afraid to think while singing – or vice-versa. Everything this trio touches works like a fine old timepiece, whether it’s Cotton-Club Ellingtonia (“Doin’ the Voom Voom”), gut-bucket blues (“There Aint No Sweet Man that’s Worth the Salt of my Tears” – and who needs a lyric sheet after a title like that?), old-school balladry (a back-door approach to “Days of Wine and Roses”) and even some rockabilly-with-quirk-sauce (“Just Married”). After you’re through listening to it, wind it up again just to see how the tunes land in your head a second or third time. And that won’t be enough.

1.) Ron Miles, Quiver (Enja/yellowbird) – This intricately-wired gadget had me at hello with “Bruise” – which, at least to these ears, compresses the wavering emotional trajectory of one’s average 24-hour existence into nine-and-a-half action-packed minutes. And, as with any album worth its ranking, it just gets better from there. You wouldn’t think you’d get a big, thick sound out of a trio comprising a trumpet (Miles), a guitar (Bill Frisell) and a trap set (Brian Blade). But this isn’t your average chamber-jazz aggregation. It’s a pocket-sized orchestra with Frisell in top form, whether laying down chords broad enough to encircle a botanic garden or spinning contrapuntal phrases that make antsy-little-bird patterns in the sky. Blade’s already established himself as the most audacious of his generation of drummers and he proves here that his ears are as big as his moxie. Miles, one of the versatile and underappreciated horn players of the present day, leads the way with a nerviness too assured to put on airs, but not afraid to think while singing – or vice-versa. Everything this trio touches works like a fine old timepiece, whether it’s Cotton-Club Ellingtonia (“Doin’ the Voom Voom”), gut-bucket blues (“There Aint No Sweet Man that’s Worth the Salt of my Tears” – and who needs a lyric sheet after a title like that?), old-school balladry (a back-door approach to “Days of Wine and Roses”) and even some rockabilly-with-quirk-sauce (“Just Married”). After you’re through listening to it, wind it up again just to see how the tunes land in your head a second or third time. And that won’t be enough.

2.) Ravi Coltrane, Spirit Fiction (Blue Note) – After more than a decade in which Ravi Coltrane’s been out-front as a leader and composer, newcomers still insist on bringing his parents into the discussion; how he and John play the same axes, how much they’re alike (or not), how Alice’s incantatory style has influenced him and on and on…No use complaining, since just about everything’s that been said on these matters so far has been true. But as of this, his most accomplished album yet, Coltrane has more than earned the right to have his artwork taken on its own distinctive terms. Enabled by co-producer Joe Lovano (about whom, more later), Coltrane triumphantly puts forth a personal vision that inquires as lithely as it asserts, that probes as decisively as it propels. He and his album benefit from having two ensembles at their disposal; a quartet with pianist Luis Perdomo, bassist Drew Gress and drummer E.J. Strickland that gives added running room for Coltrane’s massive chops (especially on such freewheeling runs as “Spring & Hudson” and the more meditative showcase for his soprano sax, “Marilyn & Tammy”) and a quintet with trumpeter Ralph Alessi, bassist James Genus, pianist Geri Allen and drummer Eric Harland that engages his conversational agility. And with individualists as those in the latter crew, one can’t help but listen as deeply as one speaks. Alessi’s compositions, “Klepto,” “Who Wants Ice Cream” and “Yellow Cat,” extract deep tone colors and slippery phrasing from Coltrane as the imperturbable Allen strings together gem-like chords with escalating force. Lovano joins in on worthwhile examinations of Ornette Coleman (“Check Out Time”) and the aforementioned late, lamented Motian (“Fantasm”).

2.) Ravi Coltrane, Spirit Fiction (Blue Note) – After more than a decade in which Ravi Coltrane’s been out-front as a leader and composer, newcomers still insist on bringing his parents into the discussion; how he and John play the same axes, how much they’re alike (or not), how Alice’s incantatory style has influenced him and on and on…No use complaining, since just about everything’s that been said on these matters so far has been true. But as of this, his most accomplished album yet, Coltrane has more than earned the right to have his artwork taken on its own distinctive terms. Enabled by co-producer Joe Lovano (about whom, more later), Coltrane triumphantly puts forth a personal vision that inquires as lithely as it asserts, that probes as decisively as it propels. He and his album benefit from having two ensembles at their disposal; a quartet with pianist Luis Perdomo, bassist Drew Gress and drummer E.J. Strickland that gives added running room for Coltrane’s massive chops (especially on such freewheeling runs as “Spring & Hudson” and the more meditative showcase for his soprano sax, “Marilyn & Tammy”) and a quintet with trumpeter Ralph Alessi, bassist James Genus, pianist Geri Allen and drummer Eric Harland that engages his conversational agility. And with individualists as those in the latter crew, one can’t help but listen as deeply as one speaks. Alessi’s compositions, “Klepto,” “Who Wants Ice Cream” and “Yellow Cat,” extract deep tone colors and slippery phrasing from Coltrane as the imperturbable Allen strings together gem-like chords with escalating force. Lovano joins in on worthwhile examinations of Ornette Coleman (“Check Out Time”) and the aforementioned late, lamented Motian (“Fantasm”).

3.) Vijay Iyer Trio, Accelerando (ACT) – There’s no respite in pianist Iyer’s assault on the traditional jazz repertoire. If anything, his trio shakes things up with even more urgency on its latest production. Yet there’s also greater authority in its overall execution given how better attuned its members are to each other’s instincts. With something as well-worn as “Human Nature” (and no, once and for all, Michael Jackson did NOT write it, but my Hartford housing-project homeboy Steve Porcaro did with John Bettis), Iyer, bassist Stephen Crump and drummer Marcus Gilmore re-jigger familiar elements into something like a grand incantation while still making it sound like something you could dance to (though it might be a slightly different dance from the one you’re prepared for). The trio also unearths unexpected theme-extending possibilities in other pop-funk guests on the playlist: “Mmmhmm” by bassist “Thundercat” Bruner and Flying Lotus and “The Star of the Story”, written by Rod Temperton for the seventies disco band Heatwave. The jazz “standards” are, of course, so left-field that Henry Threadgill’s wildly-eccentric “Little Pocket-Sized Demons” is given as straightforward a reading as can be imagined while a conventionally-swinging foundation is generously applied to Herbie Nichols’ typically-unconventional “Wildflower.” And why doesn’t it surprise that when Duke Ellington is invited to the party, his house gift is the lesser-known-than-it-should-be “Village of the Virgins,” from the maestro’s collaboration with choreographer Alvin Ailey? Iyer’s own pieces, including the explosive title track, move forward with a kind of mutant turbulence reminiscent of both Andrew Hill and Charles Mingus, while achieving a definitive shape they’ve earned on their own. It’s hard to tell at times whether harmonies are being re-imagined here as rhythms, or the other way around. Either way, you’re ready for whatever the Iyer Gang stirs up next time.

3.) Vijay Iyer Trio, Accelerando (ACT) – There’s no respite in pianist Iyer’s assault on the traditional jazz repertoire. If anything, his trio shakes things up with even more urgency on its latest production. Yet there’s also greater authority in its overall execution given how better attuned its members are to each other’s instincts. With something as well-worn as “Human Nature” (and no, once and for all, Michael Jackson did NOT write it, but my Hartford housing-project homeboy Steve Porcaro did with John Bettis), Iyer, bassist Stephen Crump and drummer Marcus Gilmore re-jigger familiar elements into something like a grand incantation while still making it sound like something you could dance to (though it might be a slightly different dance from the one you’re prepared for). The trio also unearths unexpected theme-extending possibilities in other pop-funk guests on the playlist: “Mmmhmm” by bassist “Thundercat” Bruner and Flying Lotus and “The Star of the Story”, written by Rod Temperton for the seventies disco band Heatwave. The jazz “standards” are, of course, so left-field that Henry Threadgill’s wildly-eccentric “Little Pocket-Sized Demons” is given as straightforward a reading as can be imagined while a conventionally-swinging foundation is generously applied to Herbie Nichols’ typically-unconventional “Wildflower.” And why doesn’t it surprise that when Duke Ellington is invited to the party, his house gift is the lesser-known-than-it-should-be “Village of the Virgins,” from the maestro’s collaboration with choreographer Alvin Ailey? Iyer’s own pieces, including the explosive title track, move forward with a kind of mutant turbulence reminiscent of both Andrew Hill and Charles Mingus, while achieving a definitive shape they’ve earned on their own. It’s hard to tell at times whether harmonies are being re-imagined here as rhythms, or the other way around. Either way, you’re ready for whatever the Iyer Gang stirs up next time.

4.) Henry Threadgill, Tomorrow Sunny/the Revelry, Spp (Pi) – Yup, that’s the title — even those last three letters, which look like the tail end of a URL address from an undiscovered continent, but likely stand for “species”, given the biological roots of the ensemble’s name, Zooid (pronounced “zoh-oyd” and defined as “an organic cell or organized body that has independent movement within a living organism.”) Once again, it would appear Henry Threadgill’s not going to make things easy for us. Yet if you keep in mind what that Z-word means, you can begin to understand how his group’s instrumental voices merge to form their own arresting unity from ostensible chaos. To the regular quintet — the omnipresent Threadgill on reeds, the irrepressible Liberty Elfman on guitar, Jose Davila on tuba and trombone, Stomu Takeishi on bass guitar, Elliot Humberto Kavee on percussion – cellist Christopher Hoffman is added, which broadens the range of melodic-harmonic conversation while providing additional underpinning for the rhythmic attack The frisky result is the most cohesive and accessible of Threadgill’s previous four Zooid albums. It’s almost as if the guys finally got around to what they wanted to say all along and are better able to bring all of us into the flow. Then again, maybe we’re the ones who are adjusting to the seemingly fragmented nature of this music given how increasingly static our digitized day-to-day living has become. There’s a third possibility: That the lilting dynamics of this particular disc shields more disconcerting perceptions (e.g. If “tomorrow” is “sunny,” then what’s that make “today”? And how long before “tomorrow” gets here?) But why make things harder for us than they need to be? Just revel, Humans from Earth.

4.) Henry Threadgill, Tomorrow Sunny/the Revelry, Spp (Pi) – Yup, that’s the title — even those last three letters, which look like the tail end of a URL address from an undiscovered continent, but likely stand for “species”, given the biological roots of the ensemble’s name, Zooid (pronounced “zoh-oyd” and defined as “an organic cell or organized body that has independent movement within a living organism.”) Once again, it would appear Henry Threadgill’s not going to make things easy for us. Yet if you keep in mind what that Z-word means, you can begin to understand how his group’s instrumental voices merge to form their own arresting unity from ostensible chaos. To the regular quintet — the omnipresent Threadgill on reeds, the irrepressible Liberty Elfman on guitar, Jose Davila on tuba and trombone, Stomu Takeishi on bass guitar, Elliot Humberto Kavee on percussion – cellist Christopher Hoffman is added, which broadens the range of melodic-harmonic conversation while providing additional underpinning for the rhythmic attack The frisky result is the most cohesive and accessible of Threadgill’s previous four Zooid albums. It’s almost as if the guys finally got around to what they wanted to say all along and are better able to bring all of us into the flow. Then again, maybe we’re the ones who are adjusting to the seemingly fragmented nature of this music given how increasingly static our digitized day-to-day living has become. There’s a third possibility: That the lilting dynamics of this particular disc shields more disconcerting perceptions (e.g. If “tomorrow” is “sunny,” then what’s that make “today”? And how long before “tomorrow” gets here?) But why make things harder for us than they need to be? Just revel, Humans from Earth.

5.) Luciana Souza, Duos III (Sunnyside) – Her voice is such a gorgeous instrument that it tempts producers to frame it in all manner of contexts, whether it’s Elizabeth Bishop’s poetry set to music or Chet Baker’s songbook steeped in indigo. But the formula that’s thus far worked best for Souza puts her in a studio with the finest guitarists of her native Brazil and lets them run free in duet mode with the classic repertoire of their homeland. To say this third installment is as great as its 2001 and 2005 predecessors only solidifies the stature of this career-defining trilogy. It’s hard to single out any of her accompanists, Toninho Horta, Romero Lubambo and Marco Pereira, since each manage to bring out her inner poet, chemist or dancer, whichever the occasion requires. Her interplay with Pereira on the latter’s “Dona Lu” is as ingenious as it is enchanting while Lubambo, mainstay of the invaluable Trio La Paz, collaborates with her on a transcendent, enrapturing version of Antonio Carlos Jobim’s “Dindi,” which, as with many of the other tunes here, sounds both warmly familiar and startlingly fresh.

5.) Luciana Souza, Duos III (Sunnyside) – Her voice is such a gorgeous instrument that it tempts producers to frame it in all manner of contexts, whether it’s Elizabeth Bishop’s poetry set to music or Chet Baker’s songbook steeped in indigo. But the formula that’s thus far worked best for Souza puts her in a studio with the finest guitarists of her native Brazil and lets them run free in duet mode with the classic repertoire of their homeland. To say this third installment is as great as its 2001 and 2005 predecessors only solidifies the stature of this career-defining trilogy. It’s hard to single out any of her accompanists, Toninho Horta, Romero Lubambo and Marco Pereira, since each manage to bring out her inner poet, chemist or dancer, whichever the occasion requires. Her interplay with Pereira on the latter’s “Dona Lu” is as ingenious as it is enchanting while Lubambo, mainstay of the invaluable Trio La Paz, collaborates with her on a transcendent, enrapturing version of Antonio Carlos Jobim’s “Dindi,” which, as with many of the other tunes here, sounds both warmly familiar and startlingly fresh.

6.) Dave Douglas, Be Still (Green Leaf) – Not since 1998’s Charms of the Night Sky has a Dave Douglas album beguiled as consistently as this. The soft, wistful essences of Be Still have more elegiac tinctures given that it is a series of tunes, many of them in the folk and spiritual idiom, dedicated to the memory of the trumpeter’s late mother Emily. Hence, the first verse of “This is My Father’s World” substitutes “mother” for “father.” Moreover, the quintet of Douglas, saxophonist Jon Irabagon, pianist Matt Mitchell, bassist Linda Oh and drummer Rudy Royston make the century-old hymn swing ever so gently behind the spring-water vocals of bluegrass singer Aoife O’Donovan, who shows here that she can hold her own with the jazz kids. She brings such limpid, ethereal grace to such songs as “Be Still My Soul” (whose music comes from Jean Sibelius), “Barbara Allen” and Douglas’ “Living Streams” that you almost wish she was on all the tracks. But Douglas’ own instrument is plaintive and poignant enough, even with it kicks up some dust on the more festive “Going Somewhere with You.” By its last cut, “Whither Must I Wander”, Douglas’ tribute seems suspended in a nether region between grief and acceptance, solemnity and release. It’s where most of us end up after we lose someone close to us – and where we sometimes tend to stay longer than we should. It’s that very ambivalence that makes Douglas’ musical wake seem a generous, more authentic gift to the living.

6.) Dave Douglas, Be Still (Green Leaf) – Not since 1998’s Charms of the Night Sky has a Dave Douglas album beguiled as consistently as this. The soft, wistful essences of Be Still have more elegiac tinctures given that it is a series of tunes, many of them in the folk and spiritual idiom, dedicated to the memory of the trumpeter’s late mother Emily. Hence, the first verse of “This is My Father’s World” substitutes “mother” for “father.” Moreover, the quintet of Douglas, saxophonist Jon Irabagon, pianist Matt Mitchell, bassist Linda Oh and drummer Rudy Royston make the century-old hymn swing ever so gently behind the spring-water vocals of bluegrass singer Aoife O’Donovan, who shows here that she can hold her own with the jazz kids. She brings such limpid, ethereal grace to such songs as “Be Still My Soul” (whose music comes from Jean Sibelius), “Barbara Allen” and Douglas’ “Living Streams” that you almost wish she was on all the tracks. But Douglas’ own instrument is plaintive and poignant enough, even with it kicks up some dust on the more festive “Going Somewhere with You.” By its last cut, “Whither Must I Wander”, Douglas’ tribute seems suspended in a nether region between grief and acceptance, solemnity and release. It’s where most of us end up after we lose someone close to us – and where we sometimes tend to stay longer than we should. It’s that very ambivalence that makes Douglas’ musical wake seem a generous, more authentic gift to the living.

7.) Fred Hersch Trio, Alive at the Vanguard (Palmetto) – It’s not the first album Hersch has recorded at the fabled Village Vanguard – and, now that we’re sure he’s in fine fettle, one expects it won’t be the last. But that word in the title, “Alive,” carries added weight precisely because of the pianist’s astounding recovery from an AIDS-related coma in 2008. He seems to have come back from the abyss with greater fortitude and rawer energy than he’d had before. Even the romantic lyricism, one of many attributes that prompted immediate comparisons with Bill Evans upon his earlier emergence, packs earthier, more serrated textures on such intriguing medleys as “The Wind/Moon and Sand” and “From This Moment On/The Song Is You.” He literally tosses the Evans comparisons in the spin cycle by melding “Nardis” with Ornette Coleman’s “Lonely Woman.” With his simpatico band mates, bassist John Hebert and drummer Eric McPherson, opening doors and windows for his imaginative faculties, Hersch leaps, saunters and, sometimes, stomps through those passages with a unassailable bravado that tells anybody who’s listening: Yes, I’m alive, thanks. Are you?

7.) Fred Hersch Trio, Alive at the Vanguard (Palmetto) – It’s not the first album Hersch has recorded at the fabled Village Vanguard – and, now that we’re sure he’s in fine fettle, one expects it won’t be the last. But that word in the title, “Alive,” carries added weight precisely because of the pianist’s astounding recovery from an AIDS-related coma in 2008. He seems to have come back from the abyss with greater fortitude and rawer energy than he’d had before. Even the romantic lyricism, one of many attributes that prompted immediate comparisons with Bill Evans upon his earlier emergence, packs earthier, more serrated textures on such intriguing medleys as “The Wind/Moon and Sand” and “From This Moment On/The Song Is You.” He literally tosses the Evans comparisons in the spin cycle by melding “Nardis” with Ornette Coleman’s “Lonely Woman.” With his simpatico band mates, bassist John Hebert and drummer Eric McPherson, opening doors and windows for his imaginative faculties, Hersch leaps, saunters and, sometimes, stomps through those passages with a unassailable bravado that tells anybody who’s listening: Yes, I’m alive, thanks. Are you?

8.) John Abercrombie Quartet, Within A Song (ECM) – Yes, guitarist Abercrombie is the name on the door, and he is also leader of the pack and owner of the context (jazz music from the late 1950s and early 1960s that inspired him). But from the moment Joe Lovano’s tenor saxophone starts his journey into deeper, broader variations on “Where Are You” that are worthy of the mighty Coleman Hawkins and his epoch-making 1939 recording of “Body and Soul,” he’s the one you’re most anxious to hear again throughout, whether soaring on balladry or pirouetting through Something Completely Different (e.g. Ornette Coleman’s “Blues Connotation.”) Abercrombie’s downy, single-note lyricism seems to yield so much of the floor to the greatest saxophonist of his generation that you almost overlook the unflappable expertise he shows in letting his guitar wrap itself around all manner of rhythms. Both bassist Drew Gress and drummer Joey Baron glide and pivot their way through whatever each tune requires, whether it’s the title track (Abercrombie’s crafty inversion of “Without A Song,” reminiscent of the 1961 colloquy on that standard between Jim Hall and Sonny Rollins on the latter’s “The Bridge”) or pieces by John Coltrane (“Wise One”) and Bill Evans (“Interplay”, “Sometime Ago”). It’s a delicate bit of retrospective-izing that never fawns over the past, but finds elegant ways to re-invigorate it.

8.) John Abercrombie Quartet, Within A Song (ECM) – Yes, guitarist Abercrombie is the name on the door, and he is also leader of the pack and owner of the context (jazz music from the late 1950s and early 1960s that inspired him). But from the moment Joe Lovano’s tenor saxophone starts his journey into deeper, broader variations on “Where Are You” that are worthy of the mighty Coleman Hawkins and his epoch-making 1939 recording of “Body and Soul,” he’s the one you’re most anxious to hear again throughout, whether soaring on balladry or pirouetting through Something Completely Different (e.g. Ornette Coleman’s “Blues Connotation.”) Abercrombie’s downy, single-note lyricism seems to yield so much of the floor to the greatest saxophonist of his generation that you almost overlook the unflappable expertise he shows in letting his guitar wrap itself around all manner of rhythms. Both bassist Drew Gress and drummer Joey Baron glide and pivot their way through whatever each tune requires, whether it’s the title track (Abercrombie’s crafty inversion of “Without A Song,” reminiscent of the 1961 colloquy on that standard between Jim Hall and Sonny Rollins on the latter’s “The Bridge”) or pieces by John Coltrane (“Wise One”) and Bill Evans (“Interplay”, “Sometime Ago”). It’s a delicate bit of retrospective-izing that never fawns over the past, but finds elegant ways to re-invigorate it.

9.) Sam Rivers, Dave Holland, Barry Atschul, Reunion: Live in New York (Pi) – Do the math. Rivers died a year ago this month at age 88. He recorded this in May, 2007. That would make him 84 at the time; actually, 83, since his birthday was in September. Whatever the case, you will simply not believe that a man in his eighties is capable of the kind of sustained energetic invention on saxophone and flute that Rivers displays on this epic series of live performances with old friends Holland and Atschul at Columbia University, their first performance together in a quarter-century. Those who recall how naturally lucid and enrapturing their free-form interplay was in the 1970s may not find any true astonishments in this interchange. Even so, there is always anticipation whenever Holland tosses a bass line or two into the void. Will Rivers grab at a bop-like riff and weave a few quick licks into a bird call? Will Atschul (and where has he been all this time?) pounce on his hi-hat to propel their thoughts or pry open a new path with the proverbial different drum? Maybe Rivers will move to a piano; something he rarely, if ever did back in the day. This is free jazz at its most accessible, which makes it no less challenging and much more fun. The only thing that would have made it more galvanic an event would have been an appearance by Anthony Braxton to round out the crew that was aboard for the Holland-led 1973 ECM disc, Conference of the Birds. As it is, this Reunion was more than enough to remind devotees-of-a-certain-age of the sublime, long-lost joys of listening to musicians in loft apartments make artful noise purely for inspiration’s sake.

9.) Sam Rivers, Dave Holland, Barry Atschul, Reunion: Live in New York (Pi) – Do the math. Rivers died a year ago this month at age 88. He recorded this in May, 2007. That would make him 84 at the time; actually, 83, since his birthday was in September. Whatever the case, you will simply not believe that a man in his eighties is capable of the kind of sustained energetic invention on saxophone and flute that Rivers displays on this epic series of live performances with old friends Holland and Atschul at Columbia University, their first performance together in a quarter-century. Those who recall how naturally lucid and enrapturing their free-form interplay was in the 1970s may not find any true astonishments in this interchange. Even so, there is always anticipation whenever Holland tosses a bass line or two into the void. Will Rivers grab at a bop-like riff and weave a few quick licks into a bird call? Will Atschul (and where has he been all this time?) pounce on his hi-hat to propel their thoughts or pry open a new path with the proverbial different drum? Maybe Rivers will move to a piano; something he rarely, if ever did back in the day. This is free jazz at its most accessible, which makes it no less challenging and much more fun. The only thing that would have made it more galvanic an event would have been an appearance by Anthony Braxton to round out the crew that was aboard for the Holland-led 1973 ECM disc, Conference of the Birds. As it is, this Reunion was more than enough to remind devotees-of-a-certain-age of the sublime, long-lost joys of listening to musicians in loft apartments make artful noise purely for inspiration’s sake.