Entries Tagged 'movie reviews' ↓

January 14th, 2015 — movie reviews

Enough.

Seriously.

Enough already!

Every damn year we go through some overheated foofaraw over whether a movie up for an Academy Award is somehow — how to put this — LYING about history, or History. This year’s chew toy is Selma; mostly, so far, over whether Lyndon Johnson is fairly, accurately depicted as a roadblock to Martin Luther King Jr.’s campaign against voting restrictions. Just for starters: Couldn’t such time be better spent assessing and attacking those now responsible for dismantling what King and others (including, dammit, LBJ himself) fought for a half-century before instead of showing off our erudition and/or grievances? Seems to me that’s a far more urgent matter and a FAR more productive use of one’s time than being aggrieved over who gets dissed in a dark room that smells like melted butter.

Well, the counterargument goes, for the great masses of people, movies ARE historical fact; becoming fairly or not the means through which all our history gets filtered and then hardened into something jocularly known as Collective Wisdom. At the risk of boring those who’ve heard me say such things before. especially me, I counter the counterargument for what I hope, in vain, will be the last time: If you really think that something as loose, baggy and relatively undernourished in nuance as a fictional feature film based on true stories is a plausible substitute for History itself, then you not only get the History you deserve, but the government and culture you deserve, too.

Nevertheless, as we are now less than 24 hours away from this year’s Academy Awards nominations being announced, I’m almost 99.9 percent certain than someone’s going to ask me to write about this and other similar controversies over this year’s crop of Big Movies That People Will Forget By Summer as well as those of the past. I don’t expect what I’m about to post will in any way innoculate me from such assignments. Nonetheless, since I bring this movie up every time the matter rises from the muck, I figured now was the time to make a pre-emptive strike.

So here’s something I wrote some years back on one of my favorite westerns, included in a journal listing the greatest of the genre. It says just about everything I have to say about fidelity to facts in historical movies — and how little it matters in the very long run.

MY DARLING CLEMENTINE (1946)

Director: John Ford

Cast: Henry Fonda, Victor Mature. Linda Darnell, Walter Brennan, Tim Holt, Ward Bond, Cathy Downs, John Ireland.

Even the least conscientious historian can get the bends accounting for the historical inaccuracies in My Darling Clementine. And you don’t have to get very deep into John Ford’s version of events leading to the gunfight at the O.K. Corral to find them. The movie opens with the Earp brothers herding cattle to Tombstone, Arizona in 1882 when the youngest brother James is shot dead (in the back, of course) by the rustling Clanton family.

So what’s wrong with this picture? Let’s see:

1.) James was the eldest of the Earps, not the youngest,

2.) The Earp brothers never had any cattle either heading towards or ensconced within Tombstone’s city limits and …

3.) Though James death is depicted as the spark that eventually led to the Earps’ confrontation with the Clantons at the OK Corral, that famous gunfight actually occurred in 1881 – if you’re scoring, that’s one year earlier.

We could go on and on and on, cataloguing Ford’s blatant manipulation of fact throughout this movie, which credits Stuart N. Lake’s biography, Wyatt Earp, Frontier Marshall, published two years after Earp’s death in 1929, as its principal source. But fact never mattered much to Ford, whose attitudes towards historical veracity were pithily summarized by a journalist in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence: “This is the West, sir! When the legend becomes fact, print the legend!” This gnomish sentiment both tickles and irritates the American psyche: We know something’s wrong with it, but how much do we care?

In the case of My Darling Clementine, probably not much, because the movie has over time proven more resonant and more powerful than any other about the Wyatt Earp story, no matter how historically faithful those films are.

Begin with its visual graces. Few black-and-white movies have ever conveyed such stark contrasts between the illuminated prairie landscape and the twilit corners of so-called civilization where savagery is ready to swallow innocence whole. Within this panorama, Ford orchestrates not a factual account, but his own mythic vision of history. His set pieces are adhesives to a movie lover’s memory: the town dance in an unfinished church, the woozy Shakespearean recitation sharpened by Mature’s tubercular Doc Holiday (looking as if he’s perpetually staring at his own wake) and Fonda’s Wyatt Earp in varied states of wary repose, whether in a barber’s chair or rocking jauntily in front of the “Mansion House” as Darnell’s Chihuahua hectors him.

Indeed, Fonda’s insouciant balancing act hints at mischief burrowed beneath Ford’s decorousness. It doesn’t emerge often enough to qualify as irony, but you have to wonder (as generations have) about this “say what” exchange that takes place between Earp and the saloon’s barkeep.

WYATT: Mac, you ever been in love?

MAC: No, I’ve been a bartender all my life.

At moments like this, one remembers that My Darling Clementine was made after Ford, Fonda, and co-screenwriter Winston Miller had returned from World War II military service. Comparing Fonda’s depiction of a ramrod American icon in this film with that of 1939’s Young Mr. Lincoln (also directed by Ford), one detects a serrated edge applied to the solitude and resolve in the pre-war portrayal of Lincoln. With Fonda and Ford, wartime experiences inspired in both a need for traditional American values of community, honor, and law and a lingering perception that traditions were ready for tweaking, even bending here and there.

Put another way, it is possible to claim that My Darling Clementine provides a definitive model for the standard Western film while it discloses clues to undermining that model. The willful disregard for fact is arguably part of the subversion. OK, whatever. In the end, the best way to watch this movie is just to embrace its evocative dream of a past that never was.

December 18th, 2014 — movie reviews, on writing lit -- and unlit, TV reviews

Because I don’t have to, I’m not going to bother with a Top-Ten movie list this year. This is also because there wasn’t a whole lot I saw at the multiplexes in 2014 that got me as wound up as the stuff I’m listing below. And if I bothered to enumerate the movies that did, I’d likely end up with a list that more or less looks like everybody else’s, which precisely none of us wants.

Instead, I’m going to pull together a rag basket of items that for various reasons made the most resounding connections with my frontal lobes through the prevailing media din of weapons-grade white noise and free-styling schaudenfreude. Most came out this year; some didn’t, but I got around to them for the first time this year, so they count. (My list, my rules.)

Quite likely, I’m forgetting, or blocking some stuff. It’s been that kind of year. And there were some things I couldn’t bring myself to include, whatever my absorption level. Scandal, to take one example, remains for many people I trust an irresistible sack of Screaming Yellow Zonkers. But outside of Joe Morton’s righteously Shatner-esque scenery chewing and the mad electricity vibrating in Kerry Washington’s eyeballs, I’ve found that its live-action anime antics can go on without me for at least a couple weeks at a time.

So anyway…(as this fellow might out it)

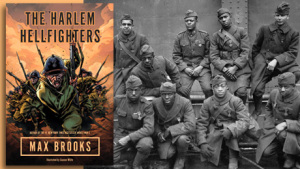

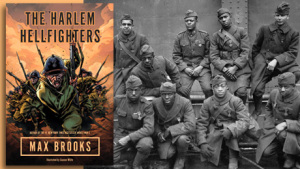

The Harlem Hellfighters by Max Brooks –Brooks made his name mythologizing the walking-dead (World War Z, The Zombie Survival Guide). But he proves himself just as conscientious in rendering factually grounded savagery in this fire-breathing graphic (in every sense) novel about the legendary all-black 369th Infantry Regiment that roared out of Harlem to fight in World War I, the hinge between post-Reconstruction’s legally-sanctioned terrorism of African Americans and the gathering pre-dawn of the civil rights movement. Though the Hellfighters’ passage from raw, often humiliated recruits to take-neither-prisoners-or-shit-from-anybody warriors is rousing, the visual depictions of squalor, disease and violence (thanks to the classic-war-comics élan of illustrator Canaan White) deepen the many ironies layered onto this saga; not the least of which was that it was only through the horrific, demeaning process of war that black men could begin proving their worthiness as American citizens – and even that wasn’t enough. To establish its own validity as historical fiction, Brooks’ account brings in such real-life badasses as James Reese Europe, Henry Lincoln Johnson and Henri Gouraud for colorful cameos. Of course, a movie is planned. Good luck trying to top this

Scarlett Johansson –I’ve already waxed rhapsodic about the commanding way she works the alien-enigmatic in the polarizing Under the Skin. By contrast, the art-house crowd showed relatively little-to-no-interest in Lucy in which she played a hapless, sponge-faced drug mule accidently injected with a drug transmuting her into a time-distorting, matter-altering, ass-kicking wonder woman. But Luc Besson’s acrylic pulp fantasy proved that few, if any movie actresses today are as cavalierly brilliant at throwing down wire-to-wire magnetism in such nutty eye candy. Manny Farber would have wallowed in the termite splendor of it all. Even her by-now borderline-gratuitous Black Widow turn in support of yet another Marvel money machine (Captain America: The Winter Soldier) retained enough droll slinkiness to make one suspect that giving the Widow her own vehicle might be a bit of a let-down. Then again, Ms. Scarlett never let me down once this year, so why dwell upon the purely speculative?

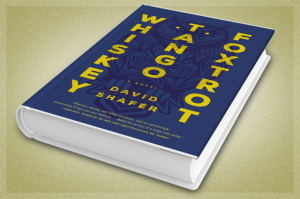

Whiskey Tango Foxtrot By David Shafer – This novel took me by surprise as it did several other critics this past summer. Up till that point, it hadn’t occurred to me that the legacies of both Richard Condon and Ross Thomas could, or even should be filled. Nevertheless, anyone whose familiarity with these authors’ works extends beyond Condon’s The Manchurian Candidate or Thomas’ The Fools In Town Are On Our Side will recognize Shafer’s sardonic humor, crafty plotting and humane characterizations as reminiscent of both authors – which is another way of saying these qualities aren’t what readers of contemporary techno-thrillers are used to. Also, much like Condon, Shafer knows, or strongly suspects, what we’re all afraid of, deep down, and finds a surrogate for this fear that’s both outrageous and plausible; in this case, a sinister cabal of one-percenters planning to seize total control of storing and transmitting information worldwide, thereby making recent abuses by the NSA, or whoever has it in for Sony Pictures, seem like benign neglect. This premise scrapes somewhat against territory controlled by what used to be called the “Cyberpunk School” as well as Thomas Pynchon, except that Shafer’s three 30-ish hero-protagonists are at once unlikely and recognizably human: an Iranian-American NCO operative who stumbles into the conspiracy so haphazardly she’s not sure what it is until it goes after her family, a self-loathing self-help guru in debt to his eyeballs who’s recruited by the cabal to be its “chief storyteller” and his estranged childhood friend, a substance-abusing misfit with a trust fund as thick as his psychiatric case file. They are all swept into an underground movement called “Dear Diary” which knows what the cabal is up to and is deploying its own secret network to bring it down. Social comedy, political melodrama and digital menace don’t always blend as well as they do here. And this is only Shafer’s first novel, meaning, as with the other masters cited above, he can only get better at this stuff from here on.

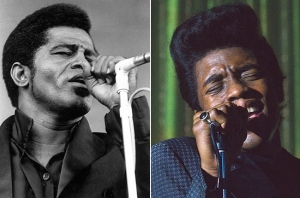

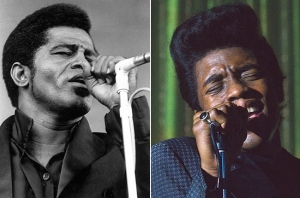

Get On Up & Mr. Dynamite: The Rise of James Brown – The former is a feature biopic; the latter an HBO-exhibited documentary. Both told me things I didn’t know about their shared subject – or, maybe more to the point, framing what I already knew about James Brown’s story in a manner that showed him as far more than an unholy force-of-nature. If I lean more towards the documentary, it’s because the revelations are more striking (not just the spectacular “what” of Brown’s showmanship, but the painstaking “how” of its components along with its savvy adjustments over time). And its testimonies are altogether more enlightening (Mick Jagger, who co-produced both, sets the record straight on how the “T.A.M.I. Show” sequence of acts really went down) I loved listening to band members let loose on what they really thought of their sometimes thoughtless boss as well as what second-generation Fabulous Flames as Bootsy Collins learned on and off the road from Brown. Tate Taylor’s biopic has a different agenda, but it strives to be just as faithful, if not always to the facts, to the facets of Brown’s fiery, hair-trigger temperament. Maybe it tried too hard. (As far as B.O. was concerned, Get On Up…didn’t.) But Chadwick Boseman’s, conscientious rendering of Brown’s tics and turbulence is almost as breathtaking to watch as one of the Godfather’s actual Soul Train appearances. Now that Boseman’s successfully portrayed two historic icons, I remain anxious to see what he can do with a Regular Guy role sometime between now and Marvel’s Black Panther movie.

FX– The third, and best, season of Veep; the harrowing, jaw-dropping single-take night scene in True Detective; Billy Crystal’s astute, heartwarming 700 Sundays; Girls and its discontents; the sheer how-can-it-possibly top-itself-again-and-again momentum of Game of Thrones…There was so much to love about HBO this year that I feel like an ingrate for professing my affection for a rival, even though there are things in both FX and HBO that I’ve neglected (American Horror Story, Boardwalk Empire) or shortchanged (The Strain, The Leftovers). Nonetheless anyplace I can find Louie, Archer, The Americans and (for me, especially) Justified is a cozy, stimulating home for my mind. Add to this the deep-dish pleasures of Fargo, whose greatness sneaked up on me the way Billy Bob Thornton’s meatiest, slimiest character since Bad Santa slithered through the frozen tundra, and of The Bridge, whose shrewd and nervy evolution from its first, somewhat derivative season went mostly unnoticed by the professional spectator classes and I’m not sure FX doesn’t have a deeper bench, pound for pound, than its bigger rivals., I prefer a lean, mean FX that takes so many worthy, edgy chances that it can be forgiven for something as lame and sad as Partners. (Never heard of it? Good. We shall speak no more.)

The Oxford American “Summer Music Issue” – I, along with many of my friends, have lots of reasons for being mad at the once-and-future Republic of Texas. But I still love its literary heritage and, most especially, its thick, spicy blend of home-grown music, which takes up C&W, R&B, Tex-Mex, swing, funk, hip-hop and even some avant-garde jazz courtesy of native son Ornette Coleman. They’re all represented on a disc accompanying a special edition of this always mind-expanding quarterly. Compiled by Rick Clark, this CD provides the kind of kicks your smarter buds used to slap together on cassette as a stocking stuffer. Besides the aforementioned Ornette (“Ramblin’”), there’s some solo Buddy Holly (“You’re the One”), early Freddy Fender (“Paloma Querida”), priceless Ray Price (“A Girl in the Night”) and the unavoidable Kinky Friedman (“We Reserve the Right to Refuse Service to You”). The left-field surprises include an especially noir-ish take of Waylon Jennings doing his signature “Just To Satisfy You,” a deep-blue rendition of “Sittin’ On Top of the World” by none other than Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys, Ruthie Foster’s espresso-laden performance of “Death Came a-Knockin’” and Port Arthur’s own Janis Joplin fronting Big Brother and The Holding Company on a “Bye, Bye, Baby” that swings as sweet as Julio Franco once did. I don’t want to shortchange the actual magazine, which includes James Bigboy Medlin’s reminiscences of working with Doug Sahm, Tamara Saviano’s portrait of Guy Clark and Joe Nick Patoski’s story about Paul English, Willie Nelson’s longtime drummer. It doesn’t beat a spring-break bar tour of Austin, but it’ll do until I get a real one someday.

August 6th, 2014 — movie reviews, TV reviews

So I watched The Maltese Falcon yesterday afternoon, partly in celebration of John Huston’s birthday, partly because I hadn’t seen it in a while. Its stock has risen and fallen with me over the decades, though never TOO low (or as low as it often fell with hard-core auteurists). Now I’m all grown-up and unequivocally accept it as a classic. But this time around, as I was watching Humphrey Bogart making his way from his office to his apartment and back again, I wasn’t thinking about him so much as I was thinking of Philip Seymour Hoffman’s star turn in A Most Wanted Man. And I realized, finally, why so many people who saw that movie are feeling even more desolated by Hoffman’s passing earlier this year.

Some perspective: Before Falcon, Bogart had been known primarily as a character actor specializing in bad-guy roles; most of them variations of Duke Mantee, the sneering fugitive killer from The Petrified Forest that established his name on stage and screen. As Sam Spade, Bogart carried some of the sinister aura he’d patented in his previous movies and was able to channel it into what Pauline Kael aptly described as an “ambiguous mixture of avarice and honor, sexuality and fear.” It was Bogart’s first “good-guy” role, though given Spade’s icy duplicity and casual cruelty one could more properly characterize it as anti-heroic, or “bad-good guy”. Nevertheless, the movie’s success made Warner Brothers and, by extension, the public regard this brooding, battered-looking fellow as someone who could be a romantic figure; a conflicted one at times, perhaps, but an enviably tough one for sure.

Philip Seymour Hoffman’s situation before Most Wanted Man was quite different from Bogart’s before Maltese Falcon. By the time he’d died of a heroin overdose this past February, Hoffman was regarded as one of our finest actors, perhaps, the greatest of his generation. His versatility won him acclaim, awards and a kind of stardom that hadn’t yet translated to heroic or romantic leads; mostly, he was cast as eccentric, sweet, awkward or malevolent characters. If Kael’s description of Bogart’s Spade could have been applied to any of Hoffman’s roles, it likely would have been Lancaster Dodd, the mercurial cult leader and title character of 2012’s The Master. It’s probable that after playing a such a magnetic composite of eccentricity, sweetness, awkwardness and malevolence Hoffman may have started wondering where else he could carry this trick bag and to what end.

So he began trying on some different wardrobe; first as a working-class mensch in God’s Pocket and as Most Wanted Man’s Gunther Bachmann, the rumpled German intelligence operative struggling to finesse the capture of a Muslim statesman suspected of funneling money to terrorists. Gunther is very much in the tradition of John Le Carre’s seedy spymasters; as with George Smiley, Gunther’s idea of getting results is to dig deep, stalk the edges, probe for soft spots and extract information as deftly as possible with no whistles and horns in sight. The strain of maintaining Gunther’s professional integrity shows in the way he wearily saunters into cafes and meeting rooms. Those working with or against Gunther’s tactics seem to have the edge because of their greater physical definition. Yet Gunther’s wooliness is deceptive, calculatedly so. Hoffman carries his character’s authority with a bruised, but stolid Old World dignity. You understand why his team will follow him everywhere and anywhere he takes them – and why his reluctant recruits end up trusting him despite their most urgent reservations.

As for the romantic part, there’s a moment, only a moment, where the possibilities make themselves apparent. It comes when Gunther, in an attempt to conceal his presence from somebody on an illuminated nighttime street, grabs his subordinate Irma (Nina Hoss) and embraces her in a faux-make-out clinch. When they break off, Irma’s hand lingers gently on Gunther’s back. The moment passes, but it’s one of the few times in director Anton Corbijn’s thriller where you’re aware of something going on just beyond the narrative’s whirring machinery.

You’re also aware of something happening with Hoffman’s screen image beyond his already-legendary chameleon chops. You think of the possibilities opened up by having someone as unkempt as a fraternity hall closet after a beer party somehow embody an heroic archetype that movie audiences throughout the world could embrace as cozily as Irma does Gunther. I’m not saying Hoffman’s performance in Most Wanted Man would have allowed him to pursue his own Casablanca or To Have and Have Not. But, putting it as painlessly as possible, it would have been great fun to see him go for it.

The recent death of James Shigeta at 85 evokes a different, but no less poignant sense of lost or forsaken possibilities. Shigeta, as many knowing and respectful tributes have mentioned, had a long and influential career as both dramatic actor and musical-comedy performer. Blessed with a deep, melodious speaking voice, Shigeta broke down racial barriers from the start of his career, playing a police detective in Samuel Fuller’s iconoclastic 1959 thriller, The Crimson Kimino, in which his character becomes romantically involved with Victoria Hall’s imperiled Caucasian witness.

It wouldn’t be the only time he’d played someone in an interracial romance or for that matter, someone in a romantic lead. And it seemed for a while as though his magnetism and grace would pay off in major stardom despite the compartments Hollywood still tended to place roles for Asian actors.

But Shigeta, though always in demand in movies and television, never became a major star; not even during a twenty-year span – the sixties and seventies – when the nature of what it meant to be a movie star was expanding enough to encompass the previously non-traditional likes of Sidney Poitier, Barbra Streisand and Dustin Hoffman. Maybe the movies couldn’t do it, but television was, and is, a different proposition, more open to tweaking expectations in the name of getting attention – and ratings.

Knowing Shigeta was originally from Hawaii made me imagine a bit of alternative history that, had it actually come to pass, might have helped make a different world. It certainly would have made for an obituary different from the ones widely circulated late last month.

So let’s all imagine, shall we?

LOS ANGELES, July 29, 2014 – James Shigeta, the groundbreaking Asian-American leading man, who achieved his greatest success as star of the long-running CBS police series, “Hawaii Five-O”, died Monday of pulmonary failure. He was 85.

Shigeta, born in what was then the Hawaii territory of the United States to Asian American parents, achieved early success as both a movie actor and as a singer who performed in the 1960 film adaptation of “Flower Drum Song,” the Rodgers-and-Hammerstein musical comedy about arranged marriages among Chinese-Americans.

But it was the role of Detective Lt. Rick Nakamura on “Hawaii Five-O” that made Shigeta a household name in America and throughout the world. In the process, it accelerated the broadening presence of non-white actors on the big and small screens in roles that traditionally went to whites.

“I will always be grateful to Rick Nakamura and everything he gave to me,” Shigeta said in later years. “Once you’ve done TV for as long as I have, you’re never a stranger, no matter where you go in the world.”

It very nearly didn’t happen, according to the late Leonard Freeman, who created and produced “Hawaii Five-O.” Back in 1967, when the idea for a series about an elite crime-fighting unit based in Honolulu reached the development stage, Freeman recalls that while casting Asian actors as cast regulars was never in doubt, the notion of the team’s leader being Asian met with resistance from CBS executives.

“They were adamant,” Freeman recalled in 1971 when the series was in its third season. “But I kept at it, telling them that, after all, we were in a time when Bill Cosby was winning Emmys as a lead character on ‘I Spy.’ But the network was certain that people weren’t ready for an Asian cop leading a series. I kept telling them that just the curiosity of the idea, along with all that beautiful scenery, would give them everything they wanted.”

Shigeta, who jumped at the chance for steady work in the land of his birth, made his own pitch to CBS executives. Apparently that was all it took – and the rest was television history, though, as Shigeta recalled later, it took a while for the show and his stardom to take hold.

“An Asian leading man on prime-time television wasn’t exactly business as usual in 1968,” he told a Time magazine interviewer in 1975. “In fact, there were so many people [at CBS] who were so sure it wouldn’t take that they were already talking about midseason replacements the same m0nth we went on the air. I got so depressed by the low expectations that by season’s end, I’d prepare for the hammer to fall and I’d start trying to figure out what to do with my life afterwards.

“Then we got renewed. But we carried those same low expectations into season two, even with all the awards we were getting. And I’d get that same sinking feeling.. Seven years later, we’re still around, so I guess everybody’s stopped worrying.”

Eventually, “Hawaii Five-O” ran twelve seasons, from 1968 to 1980. Shigeta’s good looks, silkily resonant voice and ramrod presence allowed Rick Nakamura to become as familiar to TV viewers as James Arness’ Matt Dillon from CBS’ comparably durable “Gunsmoke.” Backed by a supporting cast that included James MacArthur, Kam Fong and Gilbert Lani Kahui , whose professional name was Zulu, Shigeta’s Nakamura conveyed a deceptively impassive demeanor magnetic enough to establish what TV critic Ken Tucker would later characterize as a “paradigm of absolute cool” that actors of all nationalities would try duplicating with mixed results.

What helped seal Nakamura’s immortality was the way Shigeta would reliably intone, at or near the end of each episode, “Book ‘em, Dann-O!” to MacArthur’s Danny Williams with icy resolve.

Shigeta was nominated for Emmys six times, winning for Best Lead Actor in a Dramatic Series in 1969, 1970 and 1973. Once the show achieved steady success, Shigeta used his growing influence to ensure that other non-white actors would be given roles that would not be denigrating . He especially made sure that all his co-stars received extensive screen time, even their own episodes. MacArthur won a Best Supporting Actor Emmy in 1971 and Kahui and Fong credit their exposure on “Hawaii Five-O” for securing roles in major motion pictures, including 1988’s “Die Hard” in which they played Asian businessmen who sacrifice their lives for hostages.

MacArthur, in accepting his Emmy, credited Shigeta for the collegial atmosphere he helped sustain throughout the show’s run. “A great actor without a big ego. He’s a freak of nature!”

Shigeta parlayed his TV notoriety into a modestly successful career as a nightclub singer and recording artist. He was always puckishly proud that his 1971 version of Rod McKuen’s “Cycles” beat out Frank Sinatra’s 1968 version by reaching number 15 on the Billboard pop charts. “Something else,” he noted wryly in the Time interview, “to thank Rick Nakamura for.” (For his part, Sinatra held no grudges against Shigeta’s coup, saying, “That’s what happens when you’ve been out-acted by a fine actor.”)

By 1974, Shigeta had acquired enough clout with both the show’s producers and the network to get them to agree to casting his “Flower Drum Song” co-star Nancy Kwan as a series semi-regular. Her role as enigmatic federal agent Joanna Ming was considered as much a groundbreaker in series television as Shigeta’s and in 1978 her character was “spun off” into her own CBS action series, “Undercover,” that lasted until 1981.

Shigeta recalled being exhausted by that last season of 1979-80 and took a six-year leave-of-absence from show business. Hawaii Democrats proposed that he run for governor in 1986. Though intrigued, Shigeta demurred, insisting that, however much he wanted to effect change for people-of-color, he could do the most good in his chosen profession. Instead, he agreed to ease back into the medium in a recurring role on “L.A. Law” as Judge Danforth Akiyoshi.

He admitted that it was “funny, at first” when actors on the series would insist on muttering, “Book ‘em, Dann-O” between takes. “I’d always tell them they didn’t quite have it right,” he said. “And they were always crestfallen when I did. Gosh, I didn’t think they’d take it so personally.””

May 16th, 2014 — movie reviews

Spider-Man, amazing or not, can wait. So can Godzilla and Seth Rogin. I can afford to let them all wait because I’ve been out of the weekly movie-reviewing routine since Obama’s first term and the best part about NOT being tethered to professional routine as a moviegoer is that you can go wander at will into something that’s already been thoroughly hyped or strafed without having to organize your own 400-500-word reaction as you’re watching it. Trolling and fishing away from the mainstream makes up one of the arcane, old school joys of cinephilia; one that’s completely lost in this marketplace of shiny new toys that often shatter or wither minutes after being unwrapped. I didn’t want bright and shiny and obvious. Those will wait. I wanted oily and murky and subtle. Which never do.

And darkness was where I most wanted to go this past week to catch up on what I missed…and to do so before some of these movies went away. DC is a good movie town, but as with all markets smaller than NY or LA, the theaters in Your Nation’s Capital tend not to let smaller, relatively under-the-radar stuff linger too long in their rotation. So this was, mostly for the better, how my week went:

Blue Ruin – Did I recognize Eve Plumb towards the end of writer-director Jeremy Saulnier’s spin-dry variations on the vigilante-movie formula? I did not, remembering her mostly as a little person on “The Brady Bunch,” whose early 1970s heyday was somewhat past my use-by date for family-friendly sitcoms. Seeing the artist-formerly-known-as-Jan-Brady’s name scroll by in the cast credits, however, was enough to trigger my one misgiving about this otherwise foxy thriller about revenge-obsessed Dwight (Macon Davis), whose parents’ murder years before apparently led to his becoming a wan, accident-prone dumpster diver haunting Delaware shore parking lots and bathing in vacant summer homes. When the man jailed for his parents’ murder is released, Dwight hunts for and eventually stabs the ex-con to a gruesome death in a public rest room. So begins a rat’s nest of mutual retribution as the man’s family comes after Dwight and his sister (Amy Hargreaves), a single mother of two, who’s way too level headed to hang around this story for very long. “I’d forgive you if you were crazy,” she tells Dwight before taking her little ones off to Pittsburgh for safety’s sake. “But you’re not. You’re weak.” So much for the broad-shouldered verities of Walking Tall and Kicking Ass, which Sauliner’s script deflates with such delicacy that Dwight’s seemingly inexhaustible luck and pluck look more pathetic than heroic. Still, Davis’s doe-eyed intensity and well-oiled anxiety keep you from writing Dwight off as emphatically as his sister does.

Blue Ruin’s espresso-edgy inversion of the revenge fantasy genre along with the movie’s backwoods strip-mall ambiance has aroused comparisons to Blood Simple. That alignment’s somewhat off, I think; for one thing, Ruin somehow manages to be both leaner in execution and richer in design than the Coen Bros. 1984 neo-noir. But I also wished there were maybe a little more wit in Saulnier’s script beyond the throwaway admission from one of Dwight’s nemeses (Kevin Kolack): “Yeah, well, killin’ the mother wasn’t the brightest move on our part, I’ll give ya that.”

And while the inevitable chaos at the end buttresses the movie’s point about revenge’s pointlessness, seeing Plumb as the matriarch of Dwight’s equally vindictive (and unhinged) antagonists made me wonder whether Saulnier’s point would have been sharpened by making that family as smooth-faced and as all-American polished as…the Brady Bunch. Maybe you risk unsettling and confusing audiences by making such moves, but isn’t that what’s supposed to happen along the cutting edge? That aside, I’d still take Blue Ruin over the next serial-killer melodrama a big studio tries to put over on us.

Under the Skin – Maybe Jonathan Glazer should consider switching the title of his 2000 crime thriller, Sexy Beast with this one. The title’s unavoidable when you see Scarlett Johansson’s laconic, dark-haired predator cruising the streets of Edinburgh at all hours asking male strangers for directions or slowly stripping off her clothes as some of the poor saps who decide to ride home with her sink naked behind her into an inky pool of oblivion. Who or what Johansson’s character is and what she and her peripheral motorbike-racing enablers do with the bodies of her captives are subject to interpretation, though what little you’re permitted to see will likely make you wish you hadn’t.

In a way, Johansson’s austere, elementally restrained performance (the kind that never ever gets recognized at awards time) is a companion piece to her invisible, all-vocal and just as sensitively-realized performance in Her, another SF movie that annoyed almost as many people as it engaged Some reviewers, for instance. have complained of an overabundance of implication in Glazer’s SF-horror chamber piece. Their grousing is another reason to be depressed since, once upon a time, even mainstream audiences would have been more than OK with leaving blank spaces open for interpretation. (And not just in foreign product – or doesn’t anybody besides me like to stay up on weekends to watch Val Lewton movies like The Seventh Victim?)

Anyway, what matters in Under the Skin is what happens to Johansson’s alien invader and not to her victims, one of whom is a shy, physically deformed recluse who is almost as icily reserved as she is. Somehow, this encounter sets off a nascent curiosity within her about the nature of this earthly form she inhabits, whether checking out the voluptuous contours of her naked body or chucking up a slab of chocolate cake she tries, and fails, to consume. She’s trying to figure out what being human means. In the process, we’re trying to figure that out along with her. Some people say that theme – which is the basic raison d’etre of any science fiction worth your time – is neither original nor interesting. This beef against SF isn’t original either. But Under the Skin is, especially when framed against more hi-tech, in-your-face techno-fantasies. I wish there were more movies like it, the more obscure, the better.

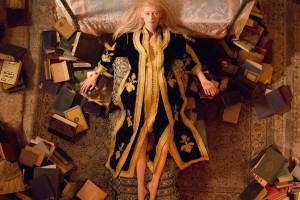

Only Lovers Left Alive –Jim Jarmusch isn’t the first art-house icon whose work acquires greater definition when it tethers itself to genre – and with any luck, he won’t be the last. While I find something to like about all his movies, even when, as in 1989’s Mystery Train or 2009’s The Limits of Control, he rambles and wanders his way around, or past, resolution, I think he is at his most arresting when his insouciant, deadpan imagination is taken up with the western (1995’s Dead Man), the crime thriller (1999’s Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai) and even the escape-from-prison subgenre (1986’s Down by Law).

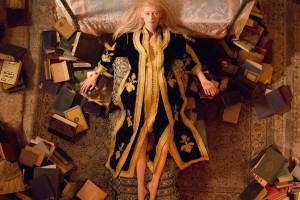

He’s finally taken up with vampires and you wonder what took him so long, especially when Only Lovers Left Alive turns out to be, all at once, his wittiest, zestiest and most touching film ever. This is the vampire movie as a hipster hang – and little else. Its two protagonists, Adam (Tom “Loki” Hiddleston) and Eve (Tilda “Orlando” Swinton who’s never been as beguiling and cuddly as she is here), are as deeply addicted to each other as they were when they met each other a century or two ago. They are also addicted to blood and lead fairly routine lives, maintaining their habits from mostly different spots on the globe; Eve wanders the curvy streets of Tangier, sheathed in silk, checking in on her vampire mentor Christopher Marlowe (John Hurt), who despite his disheveled state looks pretty hale for someone who was supposed to have been murdered at 29 years old in 1593 while Adam, a musical genius old enough to have given Schubert a hand, lives the gloomy-glam life of the reclusive rock legend inhabiting a ramshackle house in Detroit and collecting vintage guitars secured for him by a credulous idolater named Ian (Aaron Yelchin). Whenever Adam needs a supply of vintage O-Negative, he dresses up in surgical green, complete with mask and antique stethoscope, and sticks wads of cash in the hands of his connection (a droll Jeffrey Wright).

When Adam and Eve get together, life is nocturnal bliss with late-night tours of the city’s blasted streets. (“Detroit has water. It will survive when the cities of the south are burning,” Adam tells Eve with the airy assurance of someone who’s watched History’s wheels turn several dozen times.) But then, Eve’s voracious little sister Ava (Mia Wasikowska) flies in from L.A. with none of the older couple’s restraint in taking a bite with her beverage. Still, nothing, not even Ava, can harsh Adam and Eve’s mellow and you never want the hang to end, especially if those two keep their collection of 45’s rolling on the turntable. For a movie that’s bathed in shadows, Only Lovers Left Alive is as radiant as the sound of Denise LaSalle’s voice

March 21st, 2014 — movie reviews

I don’t know whether the new Veronica Mars film passes the acid test cineastes give for “theatrical film.” I do know that it was a pleasure to sit in a multiplex theater and hear an audience laugh repeatedly at snappy, clever dialogue exchanged among human beings as opposed to, say, digitally animated rodents. I have nothing whatsoever against animated rodents. But why should they get smarter things to say in movies than action heroes and the sidekicks who love them?

Anyway…Watching Veronica Mars’ Chandler-esque comedy of manners on a big screen sort of made me feel as though I were back in college when I went to the UConn Film Society’s weekend screenings of vintage screwball comedies and noir whodunits. It’s one thing to laugh at smart banter when it’s just you and a few others in a den or rec room staring at an appliance. It’s somehow more gratifying to hear your delight with brainy bon mots validated in a dark room filled with strangers. I’d almost forgotten what it was like to go to a Hollywood studio movie that delivered a slam-bang narrative drive without an accompanying discharge of exhaust, metal shavings and concussive noise.

To put all this in another way: Veronica Mars has all the modest graces and arcane charms of what we used to know and love as B-movies, whose once-secure niche was long ago ceded mostly to series television by the entertainment-industrial complex. Maybe it was inevitable and just a wee bit ironic that a big-screen revival of a prematurely cancelled TV series would evoke such lost qualities. But we’re also in this upended age where cultural arbiters are wondering whether TV series are better than feature films – and as far as most influential pundits are concerned, there is no longer a “whether.” So why shouldn’t Veronica Mars herald a return of the termite-crafty B-movie?

Much of the movie’s craftiness comes in its up-to-the-minute and (thus) close-to-the-bone depiction of all-American class conflict. The original series managed to nail down the slimier aspects of SoCal social snobbery within a YA-novel-worthy context of a button-cute teen smarty pants who fell hard from her school’s in-crowd due to a scandal that unjustly disgraced and ostracized her dad from the town sheriff’s badge to a private-investigator’s license. It’s an educated guess that many who were passionately devoted to the show – and contributed much of the funds needed to make the movie happen – identified with the marginalized status dropped upon both Veronica (Kristen Bell) and her dad Keith (Enrico Colantoni); likely believed that pulling the plug on the show after just three seasons was another personal affront from the alleged “cool kids” who ran the networks.

The movie doesn’t just retrieve its source material’s antagonism towards predatory elites, but ramps up the edginess with outrage, even (on Veronica’s face) horror upon seeing her hometown police department’s storm-trooper tactics against what appear to be minority members of an ethnic motorcycle gang. Keith’s willingness to capture this extreme-stop-and-frisk ritual on his phone camera is the kind of offhand heroism one sees in a big-screen movie about as rarely as post-Millennial police brutality is depicted in a Hollywood feature.

What’s even rarer – and in many ways, even more of a throwback to classic Hollywood days – is a movie that places in its center an ingenious, funny woman who’s neither a helpless victim nor a dour paragon (looking at you, Divergent and Hunger Games). If the Veronica Mars movie does nothing else but show America how good Kristen Bell can be when she’s given something worthwhile to say and do in front of a camera, then it will have achieved a minor miracle. On the TV show, Bell showed the kind of grit, sass, avidity and timing reminiscent of thirties screwball comediennes such as Jean Arthur, Carole Lombard and Irene Dunne. (Look at that jawline. Tell me you don’t think Dunne could have been her great-grandma.) But in just about every major motion picture she’s been in since her show discontinued in 2007, Bell seems to barely exist on screen, with the possible, if dubious exception of 2008’s Forgetting Sarah Marshall. And the only other movie she’s been in that was as successful as that was last year’s Frozen – and she was providing voice for…a digitally animated person. In Veronica the movie, she’s magnetic and feisty once again, not letting anyone shove her around, or aside. And how we missed her facility with comebacks! Where were all the writers and directors who could have brought that out? I don’t expect answers to that question any time soon.

After a week in limited release, Veronica Mars has made back roughly $2 million of its $6 million budget. It’s still too early to declare the fan-funded initiative a success or failure, given that Warner Bros still seems stingy towards its distribution. As was the case a week ago, I can count on one hand – and two fingers – the places in the DC metropolitan area that now have a Mars sign on their marquees. The studio is still offering the movie to its fans through downloads, though there have apparently been glitches in the transactions. In whatever form the movie is handed out, I’m rooting for it to succeed over the bombast and white noise of generic multiplex distractions. I’m not (necessarily) expecting Veronica Mars to make moviegoers more civilized in their expectations; nor do I anticipate that it will revive film noir or screwball wisecracks on the big screen. I’m just another fan – a “Martian”, please, not a “marshmallow” –hoping to see the cool kids proven wrong again.

February 17th, 2014 — movie reviews

Ellen DeGeneres has nothing whatsoever to be nervous about. The show will spillover past midnight and nobody will be completely happy with the overall results. Oh, and somebody will dare to tell a Seth MacFarlane joke that dies a horrible death with the audience – which didn’t hate him last year nearly as much as some of you did. So much for what I’m sure will happen. What follows is what I suppose will happen. (Predicted winners are in bold.)

Best picture

“12 Years a Slave”

“The Wolf of Wall Street”

“Captain Phillips”

“Her”

“American Hustle”

“Gravity”

“Dallas Buyers Club”

“Nebraska”

“Philomena”

It’s axiomatic that whatever the Producers’ Guild goes with as best-in- show grabs the Big One at the end of Oscar Night, no questions asked. But this year’s producers’ vote ended with both 12 Years a Slave and Gravity in a dead heat. In case you’re wondering, or scoring, that’s never happened before. So in at least this case and, maybe, one other below, there’s some genuine suspense invited to this year’s barbecue.

At times like this, Past History is your only guide. And what Past History tells you, with its arm around your shoulder and an avuncular, if apologetic intimacy, is that given the choice between voting its hopes or its fears, Hollywood always – always – chooses hope.

Those who insist on seeing moviemakers as unilaterally hard-core liberals have good reason to suspect 12 Years a Slave will be awarded Best Picture if for no other reason than as a corrective to decades of demeaning, evasive depictions of antebellum slavery in American cinema. I’d like to think so, too, even with my own guarded enthusiasm for the movie itself.

But for those who believe Hollywood carries an impregnable missionary spirit either to right historic wrongs or to reward scathing socio-political criticism, I give you, from many available and appropriate examples, 1976: A year that submitted for the academy’s approval the following Best Picture nominees: All the President’s Men, Bound for Glory, Network, Rocky and Taxi Driver. Quite a list, you’ll agree, even from this vantage point; each of these movies, even the still-relatively undervalued Bound for Glory, can be viewed today as exemplars of what American movies can do when they reach beyond convention, which is why they all have lasting value almost 40 years later.

So given the choice between, in order, a recapitulation of a newspaper’s role in bringing down a U.S. President, a biopic of a leftist troublemaking troubadour, a scathing (and, in retrospect, prophetic) takedown of the commercial television industry, the feel-good story of a South Philly leg-breaker who wills himself to the threshold of boxing immortality and a feel-bad (and, in retrospect, prophetic) story of a sad little New Yorker who enlarges himself into a deluded would-be assassin…well, even if you weren’t alive at the time, you either know or already guessed how this turned out. Rocky was the eventual and (as Past History will acknowledge with a melancholy nod) inevitable winner.

You know what that means this year? I do. I’m pretty sure I do, anyway.

Granted, both Gravity and 12 Years a Slave feature protagonists who eventually survive, if not exactly triumph, over seemingly hopeless odds. Both movies are, in their respective manner, harrowing, riveting, well conceived and wonderfully acted. But few, if any, have accused Gravity of turning history into a horror movie as some have criticized 12 Years for. Moreover, as much as Hollywood constantly yearns for a do-over on its historic mistakes, it doesn’t always like to stare directly at what its evaded or shortchanged. It knows, Lord, how it knows what needs to happen – and sooner rather than later. But does it have to be, like, right now? This minute? The movie’s out there; it’s had an impact. We’ll do more. We promise. And next time, we’ll have a full-scale blowout and really celebrate…

Blah. Blah. Blah…

I should add that a Gravity win wouldn’t break my heart at all. It was an even better, braver movie in terms of narrative tactics than most critics have acknowledged. Its director (see below) has been one of the world’s best for some time now and the movie’s anointment would be a worthy acknowledgement of his previous best. And besides, the movie’s theme — that somehow, no matter how scary things get for us when there’s no air or weight or light, we’ll figure something out – is the kind of bolstering we can use in this present-day miasma we call The New Normal. So fine, Hollywood, vote your hopes and we’ll gladly take them to heart, too. But you’d better greenlight Nat Turner and Kindred, like, yesterday. A promise is a promise.

Best director

Steve McQueen — “12 Years a Slave”

David O. Russell — “American Hustle”

Alfonso Cuaron — “Gravity”

Alexander Payne — “Nebraska”

Martin Scorsese — “The Wolf of Wall Street”

Whether his movie wins Best Picture or not, Cuaron’s had this one sewn up since last summer when the world first beheld Gravity through 3D glasses. I could spend a few seconds of my allotted time complaining that he should have received such recognition for Y Tu Mama Tambien, The Children of Men and even Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. But I wont. Virtue and virtuosity are usually their own rewards. And, for a change, both of these are given proper acknowledgement at the right time in a director’s career.

Best actor

Bruce Dern — “Nebraska”

Chiwetel Ejiofor — “12 Years a Slave”

Matthew McConaughey — “Dallas Buyers Club”

Leonardo DiCaprio — “The Wolf of Wall Street”

Christian Bale — “American Hustle”

What looked at the outset to be this category’s widest-open race in decades has by now nestled into a predictable groove. Oh, there were scattered scowls let loose into the digital ionosphere because of McConaughey’s loopy Golden Globes acceptance speech – which ultimately was, in Ralph Kramden’s deathless expression, “a bag of shells.” Dallas Buyers Club is the kind of Oscar candidate whose virtues are best absorbed through the small screen. (See Argo, if you can remember that far back.) However dazed-and-confused McConaughey comes across off-screen, you can easily imagine how his touching, physically invested on-screen rendition of a shabby-hustler-turned-impassioned-crusader captured voters’ hearts on all those DVD screeners. As Hollywood prefers to see itself as a mob of hustlers-with-hearts-of-gold, do you really think its citizenry will bypass this opportunity to pay tribute to its own self-aggrandizing heroic fantasies? It never has before, and it wont now.

Best actress

Amy Adams — “American Hustle”

Cate Blanchett — “Blue Jasmine“

Judi Dench — “Philomena”

Sandra Bullock — “Gravity”

Meryl Streep — “August: Osage County”

By contrast, what seemed a mortal lock in this category, even as early as last summer, has within the last few weeks morphed into something terribly, even poignantly vulnerable. The re-energized furor over Farrow-v-Allen may have subsided for the time being. But no one can really know how it affected voting until The Envelope is opened, which all of a sudden makes this disclosure worth staying awake for on Oscar Night. I’m going to presume that nothing changes — mostly because, whatever academy voters feelings about Dylan Farrow’s open letter and/or Woody Allen in general, they don’t like to be put into a corner. My onetime Entertainment Weekly office mate Mark Harris’s spider-sense is strong enough to intuit what might contribute to these voters’ collective grievance – and resentment:

“Oscar voters are, ludicrously, being asked to serve as jurors in a trial by op-ed: Is a vote for Blanchett to be treated as de facto indifference about the nightmare of child molestation, since Dylan Farrow has publicly contended that for a long time, she felt that any awards for Allen’s films “were a way to tell me to shut up and go away”? More to the point, is there any conceivable way to ask or answer that question without acknowledging that something horrible is being inappropriately trivialized and something trivial is being inappropriately transformed into a crisis of situational ethics? (ITALICS MINE) I’ve heard people say they think this controversy is useful because it opens up a larger discussion. I hope that who should win Best Actress isn’t the discussion they mean.”

To repeat, I’m betting it isn’t Still, the foofaraw went on just long enough for many pundits to pose the heretofore unthinkable question: If not Blanchett, then who? Given my own misgivings towards Blue Jasmine and, to a lesser extent, Blanchett’s performance, I would lean towards Adams if I had a vote. There’s even been some chatter about Dench’s crafty (in all senses) work in Philomena. But I suspect if anyone would benefit from a backlash against Blanch…I mean, Allen, it would be Bullock since she’s so widely beloved, and so was her movie. It’s still Blanchett’s to lose. But not by as much as was once believed. Whatever happens, it’ll be a chew toy for all media to deconstruct and, quite likely, dismember.

Best supporting actor

Barkhad Abdi — “Captain Phillips”

Bradley Cooper — “American Hustle”

Jonah Hill — “The Wolf of Wall Street”

Jared Leto — “Dallas Buyers Club“

Michael Fassbender — “12 Years a Slave”

Always the wildest card on the table, unless there’s a veteran involved who’s never received his due – and none can be found anywhere in this quintet. Leto was the early favorite and despite what some believed to be a more inappropriate Golden Globe acceptance speech than McConaughey’s, still owns the edge. (Again, think of how easily his movie hums into a living room with a home video player.) Still, there’s always a chance a newcomer like Abdi will repeat the precedent set by the late Haing S. Ngor in 1985 for The Killing Fields. (In both cases, there was a sense of heroism above and beyond the movie itself.) BAFTA did surprise Abdi (and us) with its own Supporting Actor prize. Then again, I’m not sure Dallas Buyers Club has crossed the pond yet. Fassbinder, for whatever it’s worth, would have been my pick. But if DiCaprio’s sadistic slaveholder in last year’s Django Unchained didn’t win (and it was a more magnetic performance than Christoph Waltz’s winning turn as the sympathetic bounty hunter), then neither shall this far more unhinged variation.

Best supporting actress

Jennifer Lawrence — “American Hustle”

Lupita Nyong’o — “12 Years a Slave“

June Squibb — “Nebraska”

Julia Roberts — “August: Osage County”

Sally Hawkins — “Blue Jasmine”

J-Law, a.k.a “Our Brando”, retains the post-position, and it’s well deserved. Nyong’o’s poised, yet assertive campaign, however, appears to have wowed academy members and watchers alike. And I’m starting to get the vague feeling that, whatever good will it carried at the season’s start, 12 Years a Slave could very well walk away from this thing empty-handed – and she’s lately been the most visible beneficiary of whatever love remains for the movie.

Best original screenplay

“American Hustle” — David O. Russell and Eric Warren Singer

“Blue Jasmine” — Woody Allen

“Her” — Spike Jonze

“Nebraska” — Bob Nelson

“Dallas Buyers Club” — Craig Borten and Melisa Wallack

Even before Dylan Farrow’s letter landed in the New York Times’ website, it was apparent that Allen ‘s script had little chance in this crowd of worthies; the most “writerly” of which is the romance between a man and his machine, which is kind of how writers see their lives these days. To repeat what historic precedent suggests: When in doubt, always go for the one that most aligns with its voters’ self-image; besides which, there happens to be some gorgeous passages in Her…so to speak.

Best adapted screenplay

“12 Years a Slave” — John Ridley

“Before Midnight” — Julie Delpy, Ethan Hawke and Richard Linklater

“The Wolf of Wall Street” — Terence Winter

“Captain Phillips” — Billy Ray

“Philomena” — Steve Coogan and Jeff Pope

As we do not live in a perfect world, Delpy, Hawke and Linklater will be unacknowledged by the academy for fashioning the most corrosive and incisive dialogue of any romantic comedy of the last twenty years. The Writers Guild has already rewarded Billy Ray, which makes him the logical favorite. But here, as elsewhere, I’m going with my gut and insist that in this instance, the writers who vote in this category will want to make a statement, if not a stand, by rewarding an African-American writer for delivering a bleak, trenchant and hauntingly effective script about antebellum slavery. It’s more hope than prophecy, but then so were black American civil rights once upon a time. (Oh, wait…)

Best documentary feature

“The Act of Killing”

“20 Feet From Stardom”

“The Square”

“Cutie and the Boxer”

“Dirty Wars”

In what it risked and how it succeeded, Act of Killing was, as far as I was concerned, the Movie of the Year. In an era more open to broad adventure and intellectual range than ours, it would have been a cult classic. It’s done well enough during awards season. But I guess we had too many other things on our minds to pay close attention to the repressed memories of Indonesian death squads. I’d be delighted if it won here, but somehow I’m thinking the academy, as with the rest of The America, is looking for something to feel good about itself, even the long-deferred emergence of backup singers from the shadows of time and neglect.

Best animated feature

“The Wind Rises”

“Frozen”

“Despicable Me 2”

“Ernest & Celestine”

“The Croods”

How I wish Hayao Miyazaki would be able to have a Mariano Rivera retirement moment on Oscar night and receive the award (and the standing ovation) he deserves for both his valedictory feature The Wind Rises and his lifetime achievement! But Frozen’s success, creative and fiscal, is like one of those large obstructions on a narrow road that you’ll just have to endure before being waved along.

Best foreign feature

“The Hunt” (Denmark)

“The Broken Circle Breakdown” (Belgium)

“The Great Beauty” (Italy)

“Omar” (Palestinian territories)

“The Missing Picture” (Cambodia)

Since I’m almost always wrong about this category, I figure, WTF, I may as well go with my heart on this one. I loved La Grande Bellezza for both rational and irrational reasons and will entertain the even crazier hope that its success in this venue will jump-start American appetites for discursive, leisurely and philosophical storytelling. Once more with feeling: WTF.

Best music (original song)

“Frozen”: “Let it Go” — Robert Lopez and Kristen Anderson-Lopez

“Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom”: “Ordinary Love” — U2, Paul Hewson

“Her”: “The Moon Song” — Karen O, Spike Jonze

“Despicable Me 2”: “Happy” — Pharrell Williams

“Alone Yet Not Alone”: “Alone Yet Not Alone” — Bruce Broughton, Dennis Spiegel

No idea whatsoever. The dart lands on Frozen. Any of the others could win. I guess. How did they come up with five nominees anyway?

Best music (original score)

“Gravity” — Steven Price

“Philomena” — Alexandre Desplat

“The Book Thief” — John Williams

“Saving Mr. Banks” — Thomas Newman

“Her” — William Butler and Owen Pallett

Isn’t Saving Mr. Banks sort of leaning on an older musical score and…No matter, because it won’t win anyway. Her’s music was as lyrical as the rest of its soundtrack.

Best cinematography

“Gravity” — Emmanuel Lubezki

“Inside Llewyn Davis” — Bruno Delbonnel

“Nebraska” — Phedon Papamichael

“Prisoners” — Roger Deakins

“The Grandmaster” — Phillippe Le Sourd

Each of these boasted striking visual conceptions. But as my faculty club friends often say to each other at odd hours of the day: “Duh.”

December 25th, 2013 — movie reviews

Top Ten? Worst Ten? Ugly-But-Brilliant Ten? I don’t know. Like…why?

There’s more than one way to sum up a year. I should start this off by saying that, contrary to what some may say, this was one of the better overall years for moving pictures and I wasn’t expecting a whole lot, given the way episodic TV has been routinely eating cinema’s gourmet lunch for at least a decade. With TV having one of its more mediocre fall seasons in decades, it was inevitable that the movies would get better at about the same time.

But I don’t need to give you a list to tell you that. There are many more of these lists to argue with from people who are even busier (if not smarter) than I am. What I prefer to submit is a potpourri of impressions, observations and pronouncements that will give you a general idea of how I reacted to the movies I saw this year. I’m not fond of the role of critic-as-magistrate (which may explain partly why no one’s now paying me to do it.) I like to think about what I’ve seen and talk it over with others. Don’t you? I’ve already rambled about 12 Years a Slave under what one would call a separate cover. And you can probably figure out what I liked a lot from what you see when you scroll down.

One other thing to say at the outset: Women will likely dominate the forthcoming discourse, but that’s because women gave me more to talk and think about in the dark this year than men. Or children. Or aliens. I’m not necessarily making a point here. Just saying…

The Incredible Shrinking Bullock

Because movie reviewers tend to a.) be pressed for time and/or lazy and b.) not take science-fiction all that seriously as a literary genre, it was inevitable that most of the comparisons they made to Gravity, positively, negatively or otherwise, were to other “in-space-no-one-can-hear-you-scream” movies as 2001: A Space Odyssey and Alien. These aren’t inept or in-apt analogies, given all the heavy-breathing spacesuits floating and crashing through all three movies. They just seemed too obvious. The first movie I thought of as I tossed my 3D glasses in the bin outside Gravity’s screening room was The Incredible Shrinking Man, whose visual effects wouldn’t make anybody gasp now, but were pretty cutting-edge for 1957. Both that Jack Arnold classic (which holds up better than you’d think) and Gravity have protagonists forced to deal with overpowering, inexplicable forces squeezing them in tighter spaces and erasing their options for survival. The telling difference (maybe I’d better flash SPOILER ALERT here) comes at the end when, though both heroes are literally stripped down to almost nothing, Shrinking Man somehow feels larger and more consequential as a human being despite his rapidly-diminishing state while astronaut Ryan Stone, though out of immediate danger, staggers off into a world that somehow feels bigger than she is. And this, you ask, is significant because…? Think of the difference in calendar years: In 1957, we integrated Little Rock’s Central High and, weeks later, Russia launched a beeping toy into orbit. This year, as I write this, there are barely enough astronauts working on Christmas Day to patch up an ailing International Space Station. And don’t even ask how voting rights did in the High Court a few months ago. We’re a lot better at special effects, but as for the rest…As I say, think about it.

Movie Critics of the Year

I only this year discovered the HISHE Network on YouTube and I have now become their stalker, looming at their door in anticipation of their next animated shot at a studio franchise. (No Desolation of Smaug, yet? No Catching Fire? You guys slacking or what? I’ve got other things to not do, OK?) The acronym, BTW, stands for How It Should Have Ended and, as you wits have likely discerned, the site’s proprietors do their own version of a blockbuster’s ending that makes you laugh and often makes more sense than the “real” thing. Because the guys and gals who work the controls of this site are knowledgeable fans of these genres, their send-ups are mostly affectionate. And it’s this admirable deficiency of snark that only magnifies their impact. It’s like having emissaries of Geek Nation sending out dispatches to the major studios and telling them, in essence, “We love this stuff, but we’re not idiots!”

Meh Dancing, Amazing Dance

I may be biased in favor of Frances Ha over other Noah Baumbach movies (most of which I’ve liked) because the title character’s struggle to make it as a modern dancer in post-Millennial New York City hits close to home these days. Also, because I’ve been exposed to different forms of choreography, I tend to see the movie as a kind of extended dance piece. Not that Greta Gerwig’s actual dancing is anything special. (It isn’t.) But I love the way she moves throughout this movie whether she’s leaping for the hell of it through Chinatown to David Bowie’s “Modern Love” or trudging warily along Parisian streets to Hot Chocolate’s “Every 1’s a Winner.” That’s what made me happy about this movie, which is something audiences and critics didn’t expect from a Noah Baumbach movie. Maybe he needed the dancing element to take the weight off. Maybe he needs to do it some more.

And the Oscar Wont (But Should) Go To….

It’s still early but I’m not hearing a lot of people throwing around Adele Exarchopopolos’ name as an Oscar prospect despite her sharing a Palme d’Or at Cannes and winning a Los Angeles Film Critics Association prize for Best Actress. Nothing whatsoever from the Golden Globes, even though she is every bit as riveting and dominant a presence in her movie as Sandra Bullock and Cate Blanchet are in theirs. The first and, often, last things people think of when they think of Blue is the Warmest Color are its NC-17 lesbian sex scenes. As lyrically enticing and obliquely suggestive as the movie’s English-language title may be, the literal translation of its French title, “The Life of Adele,” tells you everything there is to know about the story – which, prosaic as it sounds, is of a young woman’s education; sensual, yes, but also emotional and intuitive. She begins the narrative as a live wire who’s shy, moist and voracious at the same time. She comes out the other end, feeling…well, at the very least, drier. Sex may be explicit in Blue is the Warmest Color, but personality is not. And the beauty of Exarchopopolus’ performance is the way she instinctively gearshifts her character’s sensitivity, allowing us to infer what’s going on in her head while keeping us engaged with the unguarded emissions from her heart. Exarchopopolus will likely acquire greater dimension and skill as an actress. But I doubt she’ll ever again deliver anything as poignantly raw as this, and she at least should get something nice from Hollywood for her trouble.

And speaking of 20-something actresses…

Our Brando

Squares and aesthetes may have perfectly good reasons for decrying Jennifer Lawrence’s I’m-such-a-goofball talk-show appearances with their haphazard disclosures of butt-plugs and other adorable lapses in decorum. But I think these fluffernutter turns deepen her mystique more than shatter it. Public appearances are as much a performer’s art as screen acting and Lawrence is as foxily good at both playing to and subverting the hoary hype machine as she is at withholding her characters’ secrets in movies. Whether on the small or big screen, Lawrence keeps you on-edge. On the small-screen, you don’t quite know where her mouth is going next; on the big-screen, you don’t know what her face is going to do next. In neither case do these impulses feel calculated, though Lawrence is sure as hell is smart enough to know how to play both games better than anybody you can name at the moment. And that’s the real mystery: How does she know? How does any 23-year-old have the poise, the self-possession, the inner power to carry the multimillion-dollar tent pole that is The Hunger Games trilogy playing a teenage badass while simultaneously putting out back-to-back dynamo turns for David O. Russell as emotionally damaged older women? One imagines a similar frisson for audiences a half-century ago when Marlon Brando kept topping their expectations in movie after movie. The only difference is that Brando could never bring himself to create a user-friendly public persona the way Lawrence can. The more he ran away from celebrity’s power to diminish his artistry, the worse things got for him whereas Lawrence doesn’t seem to give a shit. She’s taking charge of her celebrity in ways that previous generations of actors can only envy and such confidence could help her dominate her era of movie acting as Brando, Nicholson or any male icon ever did. J-Law: Our Brando AND Our Cary Grant? Is that so hard to imagine? Forget the shticks with Conan and Dave. Watch the movies again and get back to me.

I haven’t seen this movie come up in anybody’s Ten-Best Lists.

Or this one either.

Finally, my three four five favorite lines quotes from 2013 movies:

“I feel like you’re breathing helium and I’m breathing oxygen.”

—Before Sunset

“Everything is not everything. There’s more.”

—Computer Chess

“When you’re in the middle of a story, it isn’t a story at all but rather a confusion, a dark roaring, a blindness, a wreckage of shattered glass and splintered wood, like a house in a whirlwind or else a boat crushed by the icebergs or swept over the rapids, and all aboard are powerless to stop it. It’s only afterwards that it becomes anything like a story at all, when you’re telling it to yourself or someone else.”

—Stories We Tell

“We’re all on the brink of despair, all we can do is look each other in the face, keep each other company, joke a little… Don’t you agree?”

—The Great Beauty

“Welcome to Heaven, mothafuckas!”

—This is The End

December 20th, 2013 — movie reviews

Can anybody make a serious, imaginative movie about slavery without being either ignored or picked at? Quentin Tarantino spent almost as much time shaking off flak for his flamboyant genre goof Django Unchained as he did taking bows and counting money. When Jonathan Demme made Toni Morrison’s Beloved into a far-better-in-hindsight movie in 1998, not even the Great and Powerful Oprah’s approbation of, and involvement in its production could make black people assemble en masse to see it when it was released. (Or anybody else. The cost was about $58 million; the movie made about $23 million, at best.)

At least, nobody’s ignoring 12 Years a Slave. It’s at or near the top of just about everybody’s year-end list of best movies. As of the second week of December, it’s made more than $35 million in American ticket sales with more expected around the bend in advance of Oscar season. Still, the movie has attracted its own high-visibility flak from such critics as Armond White, who believes Steve McQueen’s often-graphically violent rendering of Solomon Northrup’s testament as “torture porn” and “less a drama than an inhumane analysis.” David Edelstein, though he believed the movie “smashingly effective as melodrama,” is less fond of McQueen’s “cold, stark, deterministic” approach to the material.

For the record, I admired 12 Years a Slave far more than I loved it. An American/Hollywood director, no matter how smart or savvy, wouldn’t have trusted as much visually as McQueen does here. (In case you didn’t know, he’s black and British.) He isn’t afraid of stillness, of the tension and energy that reside in the act of waiting, as in the first frame, which in just showing the barely contained anxiety in the faces of slaves, gets the movie moving. That said, I doubt very much I will want to see it again. Do I need to watch, once again, a thin young woman getting whiskey tumblers thrown at her head and then having her back stripped of her ebony skin the way you strip a tree of its bark? I do not – and part of me wonders who would, or who needs to.

Still, because the movie is directed by a black man and is written by another (novelist John Ridley), 12 Years a Slave doesn’t get the same mauling Steven Spielberg’s Amistad (1997) received in some precincts for making ciphers of its mutinous African slaves and using their rebellion as a vehicle for white nobility. And I doubt very much the contrarian attacks on McQueen and his film will keep it from winning more awards; any more than Django’s critics kept Tarantino from collecting a screenwriting Oscar.

But no amount of gold statuettes will stop the haters from jumping on the next filmmaker who wants to take yet another hard, idiosyncratic shot at America’s Original Sin. The only solution: Take more shots, make more movies, go as odd, off-base, strange, funny, stern, cold, hot or heavy as the market can bear – and then, if you’ve got the gall, go further than that. There’s no dearth of material to draw upon, from the still largely undiscovered country of slave narratives to contemporary fiction by African American writers who are claiming autonomy over their ancestral experience through daringly imaginative means.

You like lists. Here are places to go for such material:

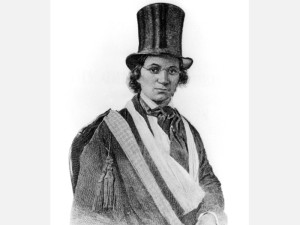

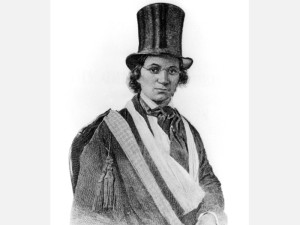

William and Ellen Craft – True story: They were married in bondage in 1846 and escaped two years later from Georgia to Philadelphia in disguise; she (above) as an invalid white man and he as “his” valet. It would take someone with an equally attuned ear for both injustice and comedy, but it could be done.

The Good Lord Bird – Being this year’s surprise National Book Award winner, James McBride’s picaresque comic saga of a young slave boy mistaken as a girl by abolitionist John Brown has likely attracted a few cautious glances from Hollywood. Sophisticated historical satires aren’t exactly meat-and-potatoes fare for multiplexes, no matter who’s involved. But it would be funny, again, if the right tone is struck.

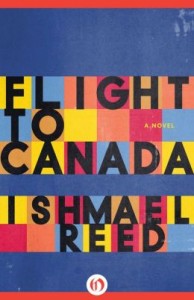

Flight to Canada — An Ishmael Reed seriocomic pastiche that’s never received the credit it deserves for initiating a wave of black novelists claiming imaginative autonomy over their ancestral past in daring, often incendiary fashion. I can’t begin to imagine who would make a movie out of it or what kind of movie it would be. But whenever or however it’s done, it’ll be different from anything that came before.

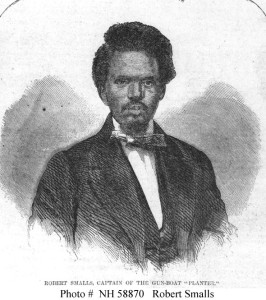

Robert Smalls Steals a Rebel Ship– Another true story; this one about a slave (above) who in 1862 commandeered a cotton freighter with a crew of 17 fellow escapees and managed to hide his identity from Confederate checkpoints, even Fort Sumter, towards the open sea until he was able to raise a white flag to Union blockaders. That alone would be a good movie, though it was just the beginning for Smalls, who later became one of the few African Americans to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives during Reconstruction. (Speaking of which, don’t you think that by now, some great movie about black folk during Reconstruction could be made to counter that damned Birth of a Nation? Just add it to the wish list.)

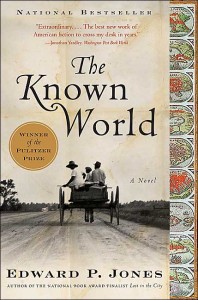

The Known World – Edward P. Jones’ award-winning novel about blacks owning black slaves already made readers’ heads spin off their necks. A movie version could magnify the shock-and-awe and I’m being REALLY optimistic when I say it could be done. But I’m betting it wouldn’t cause nearly as much trouble as…

The Confessions of Nat Turner – And, yes, I mean William Styron’s version, which has been cherished and despised in near-equal measure by black and white readers alike. America wasn’t ready for Turner in the 1830s and they still aren’t ready for him in whatever form he’s presented or imagined. Which doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be attempted.

Middle Passage and Oxherding Tale — A pair of thinking-person’s ripsnorters by Charles Johnson; the former, as with 12 Years a Slave, puts a freed slave in harm’s way as he finds himself aboard a raucous slave ship heading back to Africa to pick up more “chattel.” The latter chronicles the adventures of a half-white-half-black slave negotiating his way through both worlds with philosophic insight and canny resourcefulness.

Kindred — Let me quote from an Amazon review of the late Octavia Butler’s breakthrough SF novel: “Dana, a black woman living in Los Angeles in 1976, is inexplicably transported to 1815 to save the life of a small, red-haired boy on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. It turns out this small boy, Rufus, is one of her white slave owning ancestors, who she knows very little about. Dana continues to be called into the past to save Rufus, and frequently stays long periods of time in the slave owning South. The only way she can get back to 1976 is to be in a life threatening situation.” How is this NOT a movie waiting to happen? Why hasn’t it happened by now?

And on and on and…

September 4th, 2013 — movie reviews

If you were to ask me which of this receding summer’s movies I’d be happy to see again tomorrow, next week or even a year or two from now, they would be In a World… and Frances Ha. I’m not trying to be trendy here, even though any day now I’m expecting some renegade financial pundit to suggest that George Lucas and Steven Spielberg are on to something and that historians may regard the summer of 2013 as the beginning of the end of the popcorn tent pole era (or whatever other euphemism suits you.) I doubt the all-powerful global market has exhausted its fascination with action-hero extravaganzas and neither have I. But the omnipresence of big, noisy Hollywood franchises has aroused in me – and I suspect many more – an appetite for the smaller stuff. And I’m not in any way suggesting that “small” equals “good” or that “big” equals “mediocre” or even “predictable” or….

Never mind. Just go see In a World… while it’s still hanging around. (And it is, amazingly enough.) It made me happy in so many ways, not least for raising writer-director-star Lake Bell’s profile – and about time! I’ve been a fan of hers ever since I saw her pilfer the otherwise dreary 2007 romantic comedy, Over Her Dead Body, out from under Eva Longoria, whose TV stardom gave her top billing in what was essentially a supporting role as a bitchy ghost trying to keep Bell’s character away from the ghost’s ex-fiancée (Paul Rudd). Bell’s lanky grace and astute timing outclassed everything else in the movie, except, maybe, Rudd, with whom she was so perfectly matched that you wished they could have been airlifted to a better story, if not an alternate universe.